How much progress are we making towards global decarbonization? One way to hear that signal more clearly is to set combined wind and solar generation against all the energy the world uses. Yes, there are other clean sources of energy: hydro mainly, but also nuclear. The latter has stagnated for twenty years. The former has become increasingly variable, a victim itself of climate change. Many accountings of renewables also include biofuels, but that is a bad category: unsustainable, and not really clean. Wind and solar have another quality in their favor, as a measuring stick. They are growing quickly and reliably, and are doing so from a higher base. They replace coal and (some) oil in global powergrids, and now provide new energy to electrified transport. Increasingly therefore they sit at the nexus of a cleaned up grid, and help apply downward pressure on oil growth. Let’s see how they’re doing:

Ouch? Combined wind and solar accounted for 36.17 exajoules (EJ) out of total global energy consumption of 604.04 EJ, or 5.63%.*** After a decade of strong growth, that’s the kind of small market share that naysayers will no doubt love to cite. But it’s also the case that the two technologies have crossed above the key 5% threshold—an achievement they unlocked as early as 2016, within global power. The question: will wind+solar in total global energy make the kind of progress they’ve made already, within the global power sector, where they now have a 12.00% share? They will. Let’s talk through it.

Notice what happened during the pandemic year, 2020. Wind+solar increased share surely on the back of a collapse in global oil consumption, which reduced the base, and made for an easy, layup gain. But then notice that in 2021, as all energy consumption rebounded strongly, wind+solar not only kept up with the rebound but actually gained another half percentage point of share. The Gregor Letter has flagged this dynamic for a long while: new energy technology, because it’s cheap and fast to market, behaves like a ratchet, hoisting itself higher whether the economy is doing well or not. Indeed, new energy technology tends to thrive on chaos in the legacy energy system, powering ahead through its own intrinsic speed. This is not only true for wind+solar, but for devices too like EV or heat pumps. Europe just permanently killed a chunk of natural gas consumption, for example, which will never return.

If you haven’t spotted it already though, there’s one more development to highlight here, and it matters quite alot: energy consumption ex wind+solar has moved very little since 2019. For sure, that can be partly laid at the feet of the pandemic. But not all of it. When wind+solar started really intruding on global power, we saw the same phenomenon: they did not, and still are not, covering all marginal growth. But, they are competing well for marginal growth, and we should expect the same fight to now be engaged on a total system basis.

• data set: Wind and Solar as a Share of Total Global Energy Consumption from All Sources in EJ 2010-2022

The price of gasoline is without question connected to human happiness—in the United States. Ha. Would you expect anything less from the most automobile dependent economy in the world? One doesn’t want to be too narrow here, but gasoline affordability has long been a decent proxy for consumer sentiment in the US. Over the decades, the relationship of its cost to American purchasing power has passed through multiple regimes, and there may be an identifiable tipping point, above which, Americans turn grumpy. What we need is a long term chart depicting this evolution, so that we can make general points about the good times, and the bad times.

From the St. Louis Federal Reserve comes this chart which records, on a monthly basis, the number of gallons of gasoline an average hour of work will purchase. Before we get into the chart, here is an example: If you mowed lawns as a teenager, say, in the summer of 1985 and got paid $12.00 for an average size lot that took an hour, and gasoline at the time (which you would need to purchase) averaged about $1.12, then you’d be able to buy about 10 gallons of gasoline for your one hour’s work. As we go through the chart, we’ll see a number of changes as oil becomes cheap, expensive, or when wages stagnate, fall, or advance.

The 1990’s, with the exception of the invasion of Kuwait and the first Gulf War, was a remarkably stable period in which an hour’s worth of work bought 10 gallons of gasoline. The US was enjoying a kind of deflationary boom at the time, as efficiencies swept into the consumer sector, delivered, in part, by the advent of the internet.

The following decade was less joyous, but it started out well. An hour’s worth of labor still purchased roughly 10 gallons of gasoline, slipping at times to 9 gallons. But starting in 2004, with the war in Iraq, and China’s industrialization, we moved steadily into the “peak oil” years. US oil production stagnated. For at least 4 straight years global production also fell, in the face of steadily higher prices. You can easily see the breaking point develop as an hour’s worth of labor started buying only 6-7 gallons of gasoline, and then the final flourish was delivered in 2007 and 2008, when a labor-hour’s purchasing power crashed, buying only 4.5 gallons of gasoline. Both in the 1990’s and even this decade into the financial crisis, hourly wages were mostly ok for Americans, though a recognition was beginning to unfold that wages were not really keeping up with the economy, or consumer needs, or productivity. So this period was marked by volatility in oil prices, not a pronounced decline in purchasing power.

As the US economy began to recover from the Great Recession, and Obama became President, alot of people noticed that Americans were deeply unhappy in the 2010-2015 period. Myriad explanations were launched. But as you can see, the purchasing power of wages against gasoline was awful. And the economic recovery itself was slow, and took years to gather steam. A labor-hour fell back again into that 5-6 gallon range before starting, in 2015, a choppy recovery into the end of the decade, in 2020. Indeed, in the back half of last decade, happiness returned to the US consumer as once again a single labor-hour purchased at least 8 and sometimes 10 gallons of gasoline.

So why are Americans unhappy again, even though the economy is doing well? Yes, there are politically partisan splits on this question but let’s offer up a simpler view: inflation is like a flood which eventually recedes, but it tends to strand prices at the high water mark. A six-pack of beer or a pound of steak are no longer advancing much, but they have essentially re-priced higher along with takeout food, and simple consumer items from sponges to clothing. In this context, the Ukraine war and Putin’s energy shock knocked the labor-hour back down again to 6 gallons, and while relief did arrive in early 2023, getting us back above 8 gallons, we are now drifting south again, back towards 7 gallons.

Americans have experienced gasoline price spikes several times since the 1980’s. But none of those spikes were associated with a broader loss of purchasing power against other consumer items. Not since the 1970’s has such a comprehensive wave washed over the economy. It’s true: real wages have been making gains again, and are slightly above pre-pandemic levels. But only slightly. And what’s happening now is that Americans probably leave the supermarket, gas up the car, and by the time they get home are frustrated that all the prices they encounter are higher than just a few years ago.

Based on the totality of the chart, we might say that anytime American purchasing power of a labor-hour falls below 8 gallons of gasoline, you can predict with near certainty that consumer sentiment and other polling about the economy will go sour. If these perceptions do not improve over the next year it presents a real risk for political incumbents, and especially President Biden.

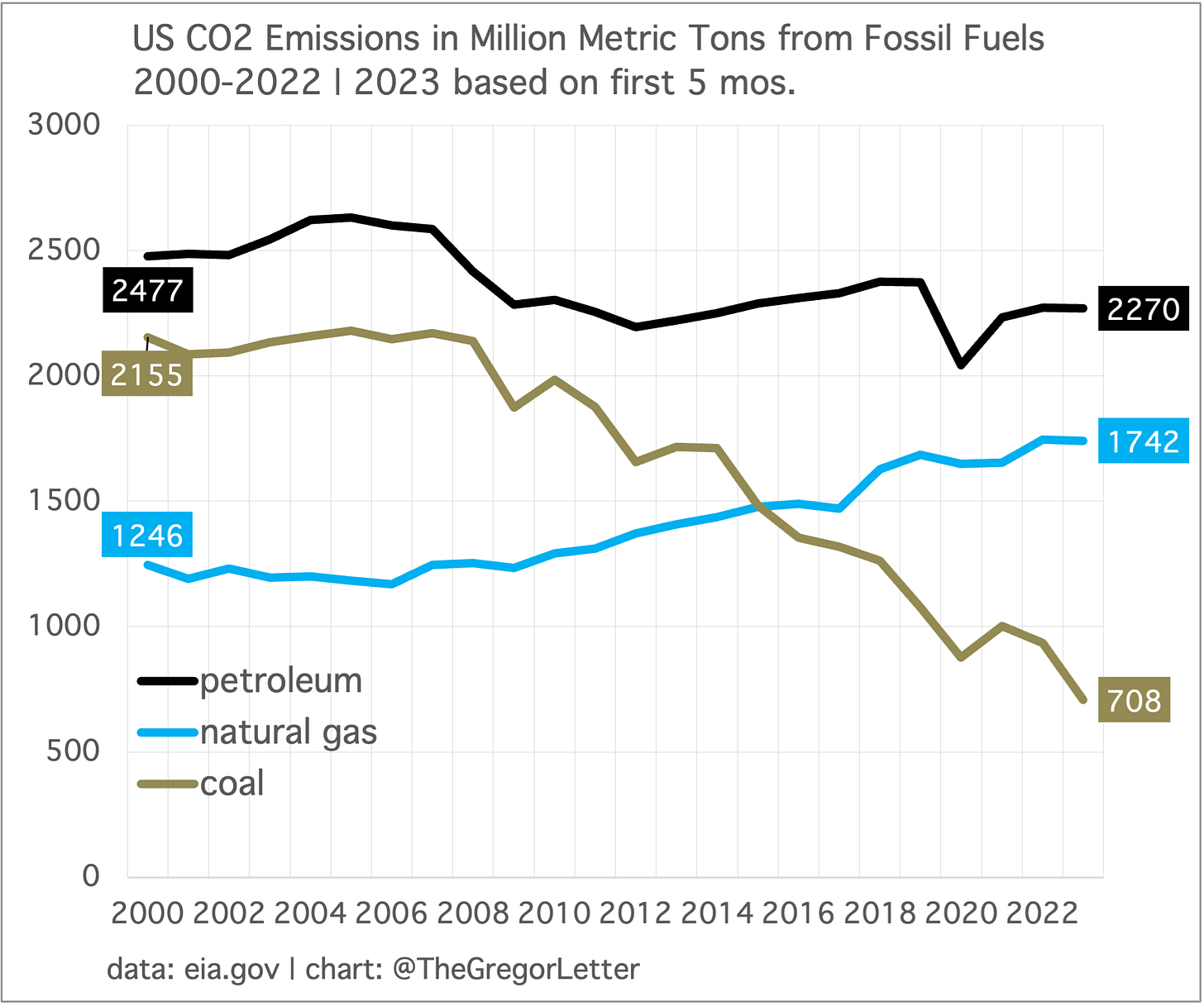

The death of coal is accelerating in the United States, highlighting the unsolved problem of oil and gas. Coal in the US is following the same path now as coal in the UK, and not long from now will soon be zeroed out. That’s great news obviously. But once again The Gregor Letter is here to remind everyone that the US is not dealing with its petroleum problem, and worse, is creating a new and growing problem in natural gas. From the highs of the first decade this century, coal emissions have collapsed from levels around 2100 million tonnes, and are on course towards just 700 million tonnes this year. That’s incredible.

But the 1400 million tonnes of emissions savings we’ve harvested in coal have been partly negated by a 500 million tonne advance in natural gas emissions during the same period. Glass half full, or half empty? An optimist might say: that was a good trade. And perhaps it was. Because we kicked off the war against coal early, we maximized the effect of emissions reductions.

The trade, or the hope, is that wind and solar will eventually kill natural gas too. The tricky problem there, however, is that we killed old coal plants and built shiny new natural gas plants with long lifecycles stretching out into the future. And of course, we continue to do almost nothing about emissions in transportation. If you want a country’s emissions to decline, you have to hit everything.

There are reasons to believe that controlling transport emissions in the Non-OECD is going to evolve far better than most fear. A complicated subject. Let’s try to simplify it. For some inexplicable reason, many western oil analysts are still applying 20th century oil adoption trajectories to the developing world in the 21st century. This is not just wrong, it’s nutty. As you know, there are already murmurings out of China that peak gasoline demand is coming far sooner than expected. Not really a surprise, is it? EV sales share in China is already at 30%, up from 5.5% in 2020. That rate of change is so torrid that if maintained there’d only be remainder/residual sales of ICE vehicles in China by the year 2030. Future adoption of personal vehicles in the Non-OECD will be largely EV, not ICE.

The other important factor sits out of sight from the habitual western view: two and three-wheelers still compose a gargantuan share of petrol powered transport across Asia and the rest of the Non-OECD, and India especially. This fleet is starting to turn over rapidly from petrol to EV. Indeed, BNEF features the heft of the global two and three-wheeler fleet prominently in their oil displacement analysis. In short, it’s a big deal.

Now to the chart. This comes from a just released IEA report, Implementing Clean Energy Transitions - Focus on Road Transport in Emerging Economies. The countries included in the IEA analysis are China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, and Mexico. The main takeaway: vehicle fleets —trucks, buses, cars, 2/3 wheelers—will expand into mid-century but the dominant drivetrain will be electric.

The figure to follow in the chart is the white dot, which stands for EV on-road share, according to the chart’s legend. Whether we forecast 60% of all on-road vehicles by 2050 or 80%, it doesn’t matter to the main question: which direction will the global vehicle fleet follow from here? Towards the ICE platform? No. The EV platform, quite obviously.

A good bet to make is that every major country that has not yet reached 30% share of wind and solar in powergrids will grow quickly now, towards that level. The UK and California have noticeably slowed in the past two years. And they may very well get going again. But leaders eventually slow some, and right now for example the fastest solar and wind growth in the US is taking place not in California, but Texas. No doubt the UK will deploy more offshore wind power. But, as The Gregor Letter has pointed out previously, both California and the UK could take a breather here on further generation growth and should instead be throwing resources and effort now into grid level storage. This is especially true for the UK, which is extremely overweight wind power. As you know, the distribution of wind supply throughout the year is highly volatile and spiky, with clumps of generation giving way to periods of calm.

We’ve already addressed in previous issues the fact that China’s solar buildout right now has gone full insane mode. And China is also starting to branch out into offshore wind, which they will no doubt pursue with similar vigor. It would not be surprising if wind and solar share advanced this year more than the two percentage points it gained from 2021 to 2022. China will easily reach 30% wind and solar share by 2030 if they keep it up.

The EU has also slowed, and the 3 percentage point gain made last year in wind and solar share really comes much more from total system demand falling during the energy shortage caused by Russia, the war, and sanctions. Indeed, the US has now fully caught up to the EU in absolute terms: both the US and the EU generated about 206 TWh last year from solar, and around 425-435 TWh from wind. The US is an energy hog by any measure, however, and that’s why the wind and solar share is much lower.

The laggard remains India, which is another way of saying its upside potential is enormous. With the right policies, India could more than double its wind and solar share by 2030, but not at the current pace, adding just a single percentage point of share from 2021 to 2022. It must be said: given India’s population, global progress towards decarbonization increasingly relies on that country’s trajectory.

—Gregor Macdonald

***Correction: there was a very minor discrepancy between the data set and the chart in Wind and Solar as a Share of Total Global Energy Consumption from All Sources in EJ 2010-2022 as originally published, which affected the wind+solar share in 10ths of a percentage point. The chart has now been updated. —GM, 5 September, 2023.