Blown Away

Monday 8 February 2021

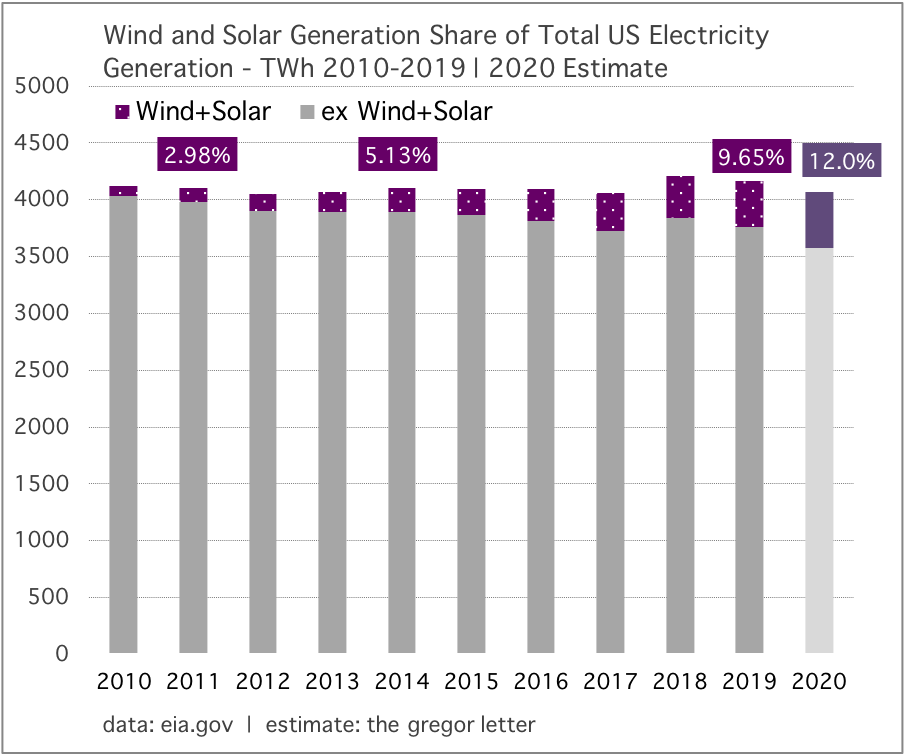

US wind power soared last year to provide 9% of the country’s electricity generation. The data comes from EIA Washington, and is an early estimate as we await final numbers for December. The latest advance makes 2020 the biggest year ever for wind capacity growth, in absolute terms, with the US adding a titanic 21 GW. This year will see a slow down (unsurprisingly) with projected additions of “just” 12.2 GW. But this too is an estimate, and 2021 could see deployments exceed forecasts (as they often do).

Last year’s stellar wind power growth has also pushed the all-important combined wind+solar share of the nation’s electricity generation well above 2019’s share of 9.65%, to 12%. To be sure, there’s a little extra pep in the share contribution as the country’s total electricity demand slightly fell during the pandemic year. But going forward, that proportional consideration will be nothing more than a fading blip.

The US as a country is now following the path of other high penetration domains like California and the UK, whose combined wind+solar share are both above 20%. The US of course is running a much larger system, generating about 4000 TWh of electricity per year for a decade now, from all sources. But here comes storage growth, which will help greatly in taking combined wind+solar to those higher penetrations. Last year’s surprise wind growth in the US echoes other upside surprises in China’s solar and wind growth, and EV adoption growth in Europe. The synergy is obvious: lots of new, clean electricity to supply an expanding global fleet of EV. Is it any wonder that financial markets are falling over themselves, to invest rapidly in these sectors?

Intercontinental solar power supply was once just a theoretical dream, but is now about to be realized between Australia and Indonesia. We are quickly running out of superlatives to describe the pace and the scale of the global solar buildout. Now comes Australia with a deliciously audacious plan to leverage its sun-blasted interior to generate large volumes of power for export, by undersea cable. Pairing a 10 GW (!) solar farm, with a 30 GW (!!!) grid battery in Australia’s Northern Territory (NT), Sun Cable will ship the power to the city-state of Singapore, on the Indonesian archipelago. The company signed the production development agreement (PDA) last week, with the NT government.

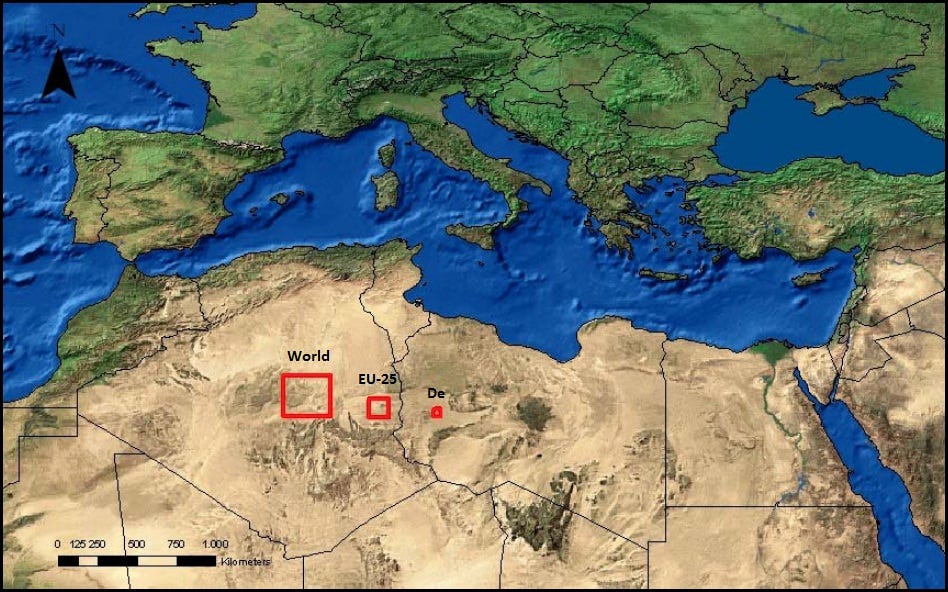

If you have watched this type of proposal for several decades you’ll recall an early iteration, the Desertec project, which proposed to do something quite similar— produce solar power in North Africa, and export it by cable to Europe. One useful teaching tool from that early proposal: it helped the public understand that a very large volume of electricity could be harnessed from domains with high solar resources. The famous ‘red-squares’ on a map of the Sahara were effective visualizations of solar’s latent power—if only the cost of solar would come down enough to make such projects economic. You’ll never guess what happened next. :-)

If you’re working on climate change in the US and transportation emissions are not your main focus, well, it’s time to ask yourself why. The largest remaining inventory of emissions lies in the transportation sector. Indeed, power sector emissions fell below transportation sector emissions more than three years ago. The decarbonization curve in US electricity is moving quickly. It does not need more policy support, or your personal time or effort. Morgan Stanley forecasts that coal will be functionally erased from the US system by 2033. That is not news. Coal is on an irrevocable collapse path, having been cut in half in the last 10 years. As I’ve pointed out previously, US coal is on the same path now as UK coal. If you are working on climate change, this should already be known to you. There is no need to work further on coal trains, or existing coal plants. US utilities already want to close them—not based on policy, but on straight line business economics. Petroleum consumption is now the problem. It’s the problem not being addressed, as the country’s petroleum consumption has been on a plateau for over a decade. And accordingly, petroleum based emissions have been remarkably steady for the past 20 years, only seeing the smallest downtick in the decade after the great recession:

There are myriad low-return-on-effort projects that still, frustratingly, seem to occupy activist efforts. For example, every hour trying to determine what ExxonMobil knew about climate change decades ago, or, analyzing whether BP’s climate goals are serious or not is an hour that will not yield any meaningful action on climate change. As the saying goes, it just doesn’t scale. That the KXL pipeline was cancelled was unquestionably a real victory for communities that would have suffered its footprint, but it won’t move the needle at all on US emissions. The US has over 190,000 miles of existing petroleum based pipelines. And pipelines themselves are not the problem. They are merely conduits to the problem. Thinking otherwise is a category error. Climate pledges made by mayors and governments are also reaching diminishing returns. Aspirational goals do, admittedly, have a pacing and leading effect. So California deciding, for example, to phase out sales of ICE vehicles by 2035 is a good thing. General Motors also announcing such phaseouts is even better. But Sacramento and the state’s largest conurbation, Los Angeles, have put out quite enough white papers now, haven’t they? Do we need more 2035 climate goal PDFs? We do not.

Here is the problem still not being forcefully addressed: miles driven by existing ICE fleets. And miles driven by existing ICE fleets are a problem that will not be quickly dislodged by adoption, or even rapid adoption of EV. Worse, the lifespan of ICE vehicles has been steadily increasing, making the fleet turnover from ICE to EV far more problematic even as EV adoption rates accelerate. Let me put this more plainly: here in the United States, ICE miles driven and their associated emissions are still mostly unpriced. Your question should not be how to achieve a lower carbon footprint in the food system, but rather, when are we going to price ICE miles driven?

Frankly, aspirational goals and long-timeline policy targets are starting to function as an avoidance scheme. An amorphous blob of unwillingness to face the harsh reality that every unit of emissions not removed sooner, collectively, becomes a far more serious problem later. We are missing therefore the opportunity to remove a significant discretionary tranche of miles driven. Right now. With even the lightest introduction of pricing schemes in major US cities we could likely prune 10% off miles driven, just for starters. The US needs to join the rest of the developed world by introducing congestion charges, and road charges. My advice: work on that first. Then, see if you have time left over to work on other areas of the climate problem.

Here in Portland, for example, we have been entertaining a tediously ill-advised plan to widen the federal highway through the city center, Interstate 5. The plan offers a solution long since disproven. At a series of public meetings in 2019, a well-spoken resident had only one vocal remark to make to the Oregon Department of Transportation: “I frankly can’t believe I’m explaining to transportation professionals that highway widening schemes don’t work. What does? Congestion charges.” I covered this story for Atlantic Media at the time and learned, essentially, that any proposal to introduce a pricing scheme on a federal highway unsurprisingly requires federal approval. Well, good news. Pete Buttigieg is now the Secretary of Transportation, Joe Biden is President, and both legislative bodies are controlled by the Democrats. Indeed, Mayor Pete—now Secretary Pete—has loudly and clearly voiced the most salient issues at play in Portland story: the highway runs near or through (as many urban highways do) lower income neighborhoods and communities of color. Open up your map and you’ll see this story repeated across the country. The US government committed this act of violence initially 75 years ago, when building out the system in the first place. So, we should be pricing emissions through urban centers not merely once for the sake of climate change, but twice to reflect the long-term damage to health and well-being.

Again: please stop working on pipelines, on fracking, and Big Oil. This is not a supply problem. This is a demand problem. Hit the existing ICE fleet with pricing schemes that nudge car owners just enough to trigger a pullback in their discretionary habits, and you will effectively hit fracking, pipelines, and Big Oil pretty hard. Please get the direction right on this equation. Harness the power of marginal demand, so that it’s working in your favor. Have you lobbied your city to introduce such pricing schemes? Because mayors, even Democratic mayors in deep blue states with populations who regard themselves as being serious about climate change, will never touch that hot rail unless you push them. The major urban conurbations here on the west coast don’t even have toll roads. But they represent a very large volume of US transportation emissions, especially the granddaddy of them all: the five counties that compose Southern California. London first introduced such charges 20 years ago. After the initial retort from the public, London has used that initial trip-charge scheme as a platform on which to build additional charges, now based on emissions. No one is crying about it in London. Indeed, from 2010 through 2019, UK oil consumption is down 3.8%. Not stellar, but at least this tells a story of demand-growth suppression.

The US in the same period saw oil demand shift by roughly the same amount, 3.5%, but to the upside. See the problem? We rebounded from the great recession to the existing automobile fleet. So did the UK. But the UK found a way to suppress the rebound. We did not. And the same rebound is happening all over again, as we emerge from last year’s lows in oil demand. To sum up: this is the most important problem to work on right now in the US. It’s also the problem most politically challenging. But doing so will yield the biggest hit to US emissions in the present, and emissions growth in the near future. We must hit emissions now, well before 2035, when all those attractive (but not yet uncomfortable) goals are set to land.

General Motors released a splashy, marquis ad for electric vehicles during the Super Bowl. Full penetration of EV into the US vehicle fleet is simply not going to happen unless the legacy automakers, not just pure EV manufacturers, participate. So it was extremely encouraging to see GM hire Kenan Thompson, Awkwafina, and Will Ferrell for a 90 second spot that hilariously pokes fun at Norway’s world-beating dominance in EV adoption—and by do so, admits America is far behind. That last part (how we’re behind) is the genius of the ad because it plants a stake in the ground to mark our current position, and leaves the viewer with the feeling of wanting to catch up. Simplistic? Perhaps. But really, let’s just embrace the spirit of whatever it takes.

Ford Motor will release the Mustang Mach E, a crossover SUV, precisely the type of vehicle sought in the US market. Again, more good news. Trucks and SUVs are the vehicle types this market has been preferencing for a decade now. The EV Hummer from GM, the proposed Ford 150 EV, and the Rivian Truck won’t be to everyone’s liking, and that’s fine. Volkswagen, BMW, Tesla, and the Korean automakers will likely grab alot of market share in US cities. But to get full adoption of EV in the US, the EV truck is how you’ll gain traction at the jobsite, and the short wheelbase crossover is how you’ll conquer the suburbs.

Rivian made e-delivery vans are already on the streets of Los Angeles, for Amazon. According to industry reporting, Amazon has ordered 100,000 of the vans. What’s particularly encouraging is that this rollout comes just 18 months after the company received alot of internal pressure to reduce its carbon footprint. And eventually Amazon came up with a plan.

The US Department of Transportation’s annual budget is roughly north of $85 billion. This has led some to conclude there are not enough resources or leverage at USDOT to make the changes the country so desperately needs. Perhaps that’s true. But it must also be said that USDOT has a policy transmission mechanism through 50 state level DOTs, whose combined resources well exceed the federal DOT budget. The math is not entirely straightforward: In 2019, combined state DOTs spent about $2.1 trillion, with a quarter of that funding coming from federal sources, according to the Eno Center for Transportation. But the bottom line is clear: we should think of America’s combined transportation complex as having more than enough policy leverage to pull back hugely, if not entirely, from road building and head off in new directions. While it’s to be expected Secretary Pete (his new twitter handle) will trot out long term goals, there is simply no excuse now to avoid immediate action. What’s immediate? This year. A city like Portland, all ready to go, should roll out congestion charges this year. We don’t need more studies. What we need is rock n’ roll:

Just to remind: the Oil Fall series will receive its update sometime this quarter, and will be sent out free to all purchasers of the original title.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.