Building Clean

Monday 8 August 2022

Major climate legislation in both Australia and the United States is poised to finally punch through longstanding roadblocks from opposition parties. Both countries have substantial fossil fuel and extractive industries which, in the case of Australia, largely dominate its exports, and in the case of the US exert powerful legislative influence within a much larger, more diversified economy. The advent of such sweeping legislation is a kind of double miracle: not only will the impacts be large and long-lasting, but it’s a surprise they are happening at all. The politics of climate are changing.

The best way to think about the US version, the Inflation Reduction Act or IRA, is that it’s a deployment and infrastructure bill, one that will distribute itself more deeply, more broadly into every corner of the nation. Up until this point, climate policy in the US has largely concentrated on the building of utility scale wind and solar, which has expressed itself as concentrations of windpower in the great plains, and solar in the drylands of the west. Moreover, US incentives historically have run for shorter time periods, with industries affected always having to face dates of expiration. The current bill, which is likely to pass the US upper chamber first, will be far more effective on a social axis— bringing decarbonization to under represented communities—and on an industrial axis, bringing incentive packages to research, manufacturing, and broader renewable deployment. The US will see far greater deployment of rooftop solar, for example, on commercial and industrial buildings, and will see renewable and grid investment finally penetrate disadvantaged states or cities. From a top down view, the legislation will lower emissions to the year 2030 by roughly 31-44% compared to 2005 levels, in the context of the roughly 24-35% decline already expected, in an estimate by The Rhodium Group.

On a more detailed level, the US package will catalyze production of heat pumps, investment in electrolysis for hydrogen production, and contains other single shot initiatives to electrify government vehicle fleets, and decarbonize government more generally. There is also a major push on carbon capture which, overall, will probably start guiding industrial use of heat-generating resources over to hydrogen and clean electricity. In other words, while the US bill links backward to the types of incentive structures seen before—wind, solar, electric vehicle tax rebates—it pushes forward more decisively to persuade the US construction, industrial, and utility industries to start transforming the harder-to-abate areas that lie outside of transportation or utility scale power.

The general prospect of the US legislation is as follows: let’s say an area of Detroit or Philadelphia is being redeveloped on the back of a local university’s expansion or perhaps just the opening up that comes from economic growth, and a new demand for housing. The US legislation is going to hit multiple points in that expansion in building materials, grid transmission through microgrids, and the deployment of ancillary structure features like heat pumps, energy efficiency, and rooftop solar. In other words, when considering the next round of economic growth, the US has now decided it’s far better to build clean, from the beginning.

There are a few twists and turns in the bill too. These are artifacts of the effort to get two moderate if not recalcitrant senators—Manchin from the coal country of West Virginia, and Sinema from very conservative Arizona—to sign on to the legislation. Manchin added a mechanism to the bill that commits the US government to free up acreage for oil and gas drilling as an offset to wind and solar allotments. On its face, that sounds really bad for climate. But wait! What if this provision ensnares the oil and gas industry into supporting the bill (which they do) because this shiny object seems so attractive—but then winds up as a weak, largely symbolic offset? We have to remember that millions of acres of land for oil and gas drilling have 1. already been allotted but still never used. 2. will continue to be allotted at a slower rate regardless. The Gregor Letter already predicts, therefore, that oil and gas acreage allotted to the industry (and actually drilled) will wind up being far, far, less than many fear.

The Sinema twist in the bill is also intriguing. There’s an arcane and lucrative tax provision in the US code that allows the private equity industry to pay exceedingly low taxes (no doubt, originally conceived as a way to offset the industry’s risk) and it’s called carried interest. Arizona’s Sinema is oddly protective of this measure, and in the late version of the bill carried interest was axed as a revenue raising measure. (Remember, the reason Manchin not only singed on to the bill but has been out on the wires selling it, is that he wanted revenue raising to match spending). Just one vote shy of 50 votes, therefore, the Democrats ceded carried interest back to Sinema, and then plugged the hole instead with a surcharge on corporate share buybacks. This is all absurd of course. But it may, like the oil and gas land lease sales, produce an unexpected outcome. You see, the past decade has seen an orgy of corporate share buybacks which is another way of saying they didn’t hire, and they didn’t invest. Now with a disincentive to use corporate cash they may decided to devote some capital to growth.

The Gregor Letter therefore sees this legislation as a far more forward looking policy that will dominate the scene not for 2-5 years, but for a full decade. One of the chronic problems the US has lapsed into for a long while is a maddening failure to invest for the future. This bill may have the effect of organizing economic activity to do just that. If so, this version of climate action may begin to cure several longstanding, American ailments in a single stroke.

Advanced modeling and analysis of the US climate bill, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), is increasingly accessible.

• Reaching back to the Rhodium Group analysis already mentioned, their top-down chart is a useful guide to the legislation’s overall impact:

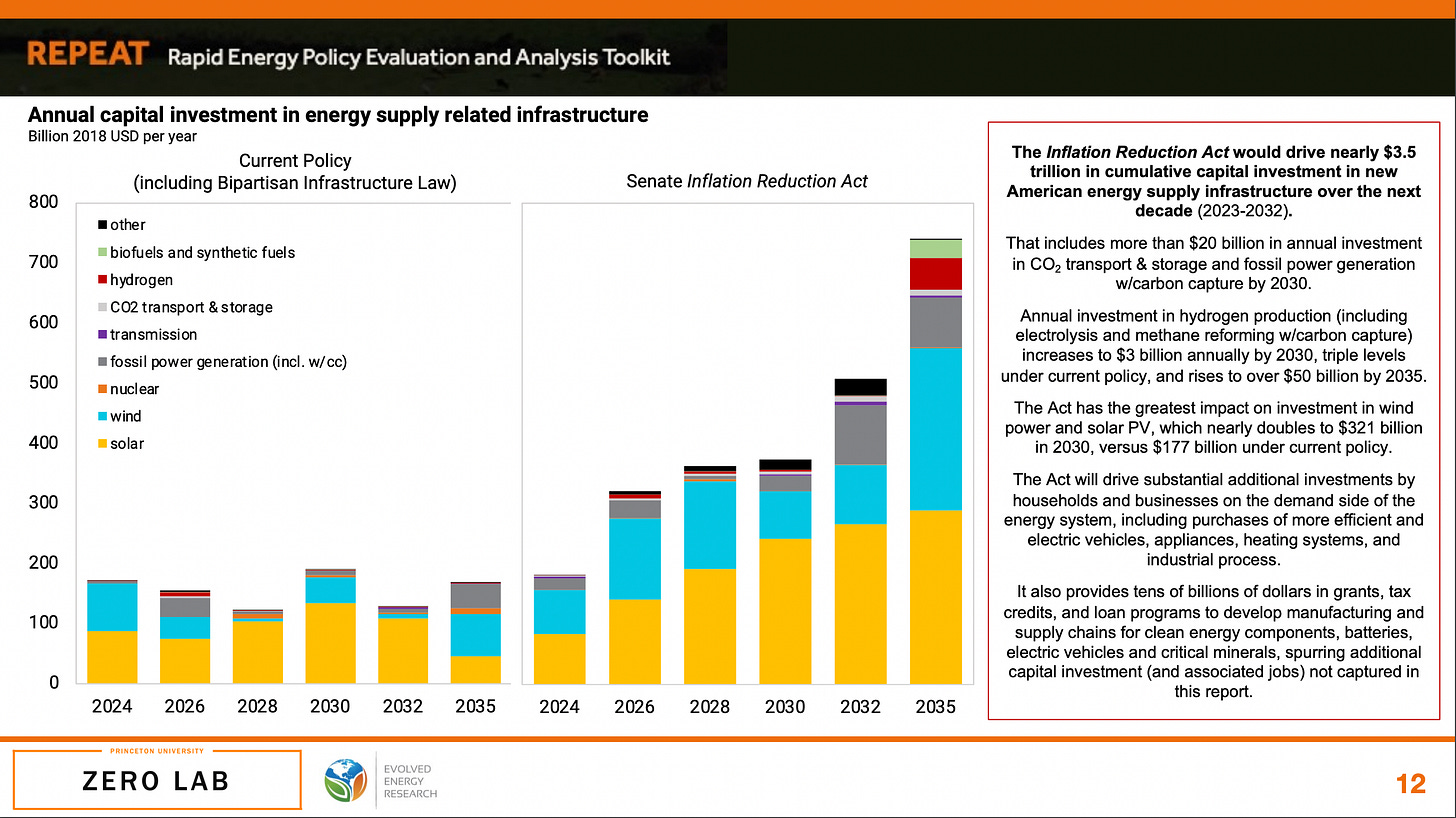

• At Princeton University, the Zero Lab’s REPEAT project has a nice slide deck (PDF) showing a number of outcomes across sectors. Note: REPEAT also finds a similar 42% overall reduction in emissions compared to the 2005 baseline. Because more rapid growth of wind and solar is a fairly standard part of this legislation (and likely would be, under any policy of this type) a slide worth reviewing is one that sees this growth through the lens of increased annual capital investment. What stands out here is the impact on hydrogen related investment. Yes, it starts out “small” but it triples levels under current policy. And though it’s hard to see on the histograms below (because the unit of account is hundreds of billions) hydrogen related investment ramps steadily to $3 billion annually by 2030, with more to come thereafter:

• From Energy Innovation, out of San Francisco, we get a jobs chart from their report, Modeling the Inflation Reduction Act Using The Energy Policy Simulator (opens to PDF):

• Washington, DC based Resources for the Future (RFF) has taken a look at potential effects on retail electricity prices. From a political and social perspective this is important, because power pricing is where policy intersects with the voting public. If RFF is right, and retail prices either decline or simply stop going up, then the prospect for future, additional climate legislation is bright:

• Finally, this Wednesday 10 August, RFF will host an online panel discussion of the IRA starting at 1300 hours Washington, DC time. Details available here.

Late breaking news: as The Gregor Letter goes to press, the final vote in the US Senate has passed the IRA. The bill moves on to the lower chamber, the House of Representatives, later this week where it is expected to pass easily.

Climate progress remains a tale of two cities. The growth of clean energy technology is nothing less than spectacular, while the world’s dependency on fossil fuels remains stubbornly hard to dislodge. Perhaps no better portrait of our current position came through last year, when wind and solar growth blasted ever higher. And then coal—relic of the 19th century, and now a menace to the 21st—recouped seven years of mild consumption declines and nearly made a new all time high. For recent coverage of both coal and solar growth, please see previous letters Midyear Chartbook I, and also Speed of Solar.

The nasty problem to solve in the fossil fuel legacy system is the installed base, which pumps out path dependency every day, every month, every year. As Mark Lewis, formerly of BNP Paribas and now of Andurand Capital Management explained years ago, the world is set up to conveniently, quickly, and affordably deliver the next unit of fossil fuels. In other words, oil, gas, and coal enjoy a global network of dispensers—think of them as vending machines—always ready to distribute your preferred energy packet. And that global distribution network delivers a big part of the affordability of fossil fuels.

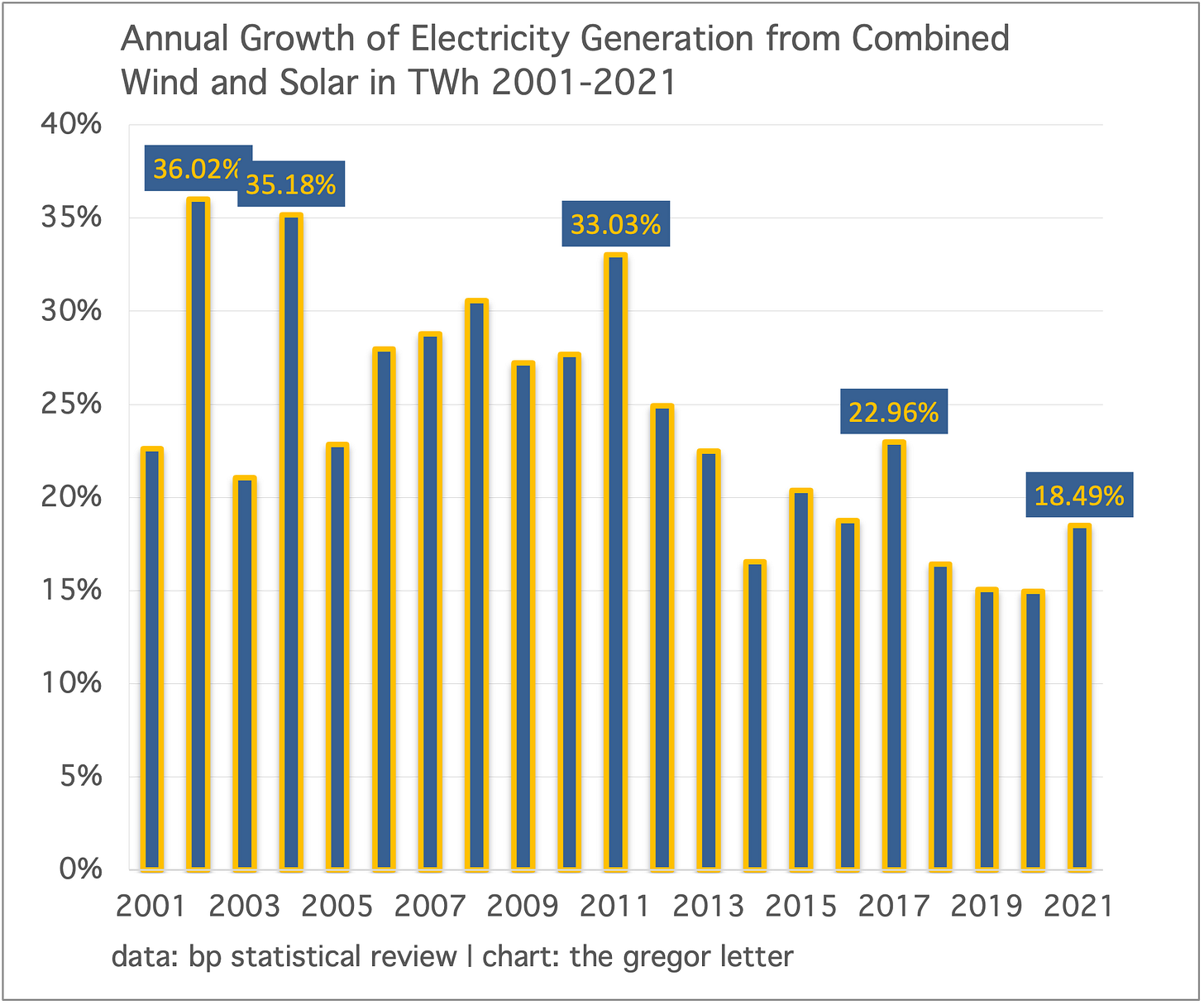

That’s why the buildout of wind and solar is so important. In the rollout, what’s really happening is a new platform is being built that’s crucial to everything we want to do with clean electricity. Powering transportation, hydrogen production, building heat, and eventually steelmaking and cement production. We can’t decarbonize without electricity, and we can’t clean up all the services and processes without that electricity being clean. Yes, this is obvious. But it’s worth stating, because as Buckminster Fuller once observed: you’ll generally find that reforming the old system is hard; harder even than building a new system. To that point, it’s astonishing that global power generation from wind and solar is still able to grow at nearly 20% annually, now that the two sources combined account for more than 10% of global power generation.

The problem is legacy infrastructure. Last year, China’s massive and overbuilt coal network, which has been underutilized for years, was swiftly put back into action on the back of a fast economic recovery, and a global scramble for LNG. Climate scientists like Glen Peters at Oslo based CICERO warned about this risk for years. And it’s especially frustrating given that coal has crashed, and crashed hard, in the US and Europe. Is coal growing? No. But it persists.

The Gregor Letter first began to write about this phenomenon over two and half years ago, in Plateau Problems. From a trailing, decade long view it is absolutely fantastic news that global coal peaked in 2014, that OECD oil consumption peaked in 2005, that California gasoline consumption peaked a decade ago, and so on. But now it’s 2022, and still we wait for many fossil fuel consumption profiles, from the global level down to the country or regional level, to go ahead and decline already!

To give a darkly comical example, a political dustup occurred recently when the US EIA discovered that July 2022 gasoline demand was actually lower than July 2020 gasoline demand. Hyper-partisans were immediately convinced that the Biden Administration was playing with the numbers to drive oil prices lower. Now comes the humor: EIA’s estimate showed July 2022 demand was barely below July 2020 demand, and even if this is not revised (it will be) it frankly doesn’t matter either way. Here’s why: US gasoline peaked over 17 years ago and has done nothing but oscillate since. During that time US population has grown a full 10% from 300 to 330 million, but gasoline consumption refuses to fall. Admittedly, the signs are encouraging. First half 2022 consumption has come in at a rather low level. But would this have happened if petrol were as cheap as ever this year? Probably not.

As The Gregor Letter has shown previously, one of the ways consumption can persist on a stubbornly long plateau occurs when a very large consumer continues to grow while a collection of other users enter a mix of both decline, and stasis. This precisely describes the global oil market in which the Non-OECD is almost entirely composed of consumption growers, while the OECD is composed of decliners and flatliners.

Now that the United States is on the threshold of a real, decade-long, comprehensive climate policy—one that will deploy enormous volumes of new wind and solar, and which will incentivize EVs for a sustained period—the prospect of finally getting off the oil plateau finally seems real. Other developmental lines were leading in this direction already. But the sobering reality is this: not only must oil consumption in the US enter decline (finally joining Europe) but China consumption at the very least must stop growing. Because the rest of the Non-OECD will likely stitch together user growth for a while yet.

—Gregor Macdonald