Los Angeles area transit ridership soared this month after a sudden freeway closure, reminding us that the US runs an underpriced system for private vehicles which competes directly with public transportation. According to LA Metro and the Mayor’s Office, the arson fire which shut down a portion of the Santa Monica Freeway on 12 November triggered a quick 10% surge of passengers to the Expo Line, which starts in East Los Angeles and passes through downtown. Early estimates suggested repairs to interstate 10 would take up to five weeks. However, in a twist, that timeline was shortened greatly as crews worked tirelessly, and had the freeway up and running 8 days later. The emergency-level repair time echoed a similar fast fix to I-95 in Philadelphia just this summer. For those who have watched American cities take ten years to study congestion tolling, with no results, or several years just to put in a few bike lanes, often with poor results, a common question arose: why can’t we do this with everything?

Los Angeles began building out its rail system more than twenty-five years ago. It is singularly the largest buildout of commuter-oriented rail undertaken in the post-war, vehicle era; and Metro is still building. But during that entire time, the LA Metro has had to compete with a well funded state and federal government highway system that is in direct competition with L.A.’s effort to attract riders. This is nutty, bonkers, and downright irrational. During the 20th century, many East Coast cities introduced either tolls, or bridge fees, that often kick in for passenger vehicles when driving to an urban core. So it’s common for drivers to leave their car at a rail station where the fare and the parking fee are more attractive than downtown parking. To be fair, Los Angeles had the unique task of retrofitting a post-war sprawl city. This has often led to local sniping that “the metro doesn’t go anywhere.” Well, today you can wake up in Pasadena and ride all the way to the beach in Santa Monica.

California’s transportation budget for the current fiscal year comes in at roughly $20 billion, or 6.8%, of the total at $311 billion. By comparison, LA Metro’s budget for the year is at $9 billion. Metro funds itself largely through a chain of historical sales taxes enacted through local public measures, in addition to fares, borrowings, and fluctuating support from the federal government. The state budget is a far heavier recipient of federal dollars though, which greatly supports highway spending. Metro therefore is mainly a project underwritten by the people of LA and surrounding counties. Meanwhile, this same region is populated by no less than five federal highways and all of them are used as local arteries for working, and commuting. Not a single user fee is required.

The state of California has taken moderate steps over the years to disincentivize driving ICE cars. These come mainly through extra fees to be paid during registration renewal. To these fees, California has steadily raised the petrol tax. Combined with a structural refining shortage which means alot of petrol pumped in California has to be imported, prices for US gasoline tend to be quite high—often as much as $1.00-$1.50 higher than the rest of the country. Given inflation in the price of cars themselves, which has led to declining vehicle sales, that may be one of several reasons why California petrol demand is finally in gentle decline. And, why Metro ridership was already starting to grow again, as it seeks to recover to pre-pandemic levels.

Southern California needs to introduce congestion fees. A simple user-fee proposition would start with a $5 dollar day pass for driving everywhere in the LA Basin. This is the fee Metro charges for its own day pass. At the start of such a program, fee-design could give a break to low income people, and perhaps everyone could be granted something like two free driving days per week. The insight offered by the 8-9 day loss of I-10 near downtown is that there’s a ton of discretionary driving that a mere nudge would dislocate. Once a fee, any kind of fee, and even a small fee is introduced, an initial layer of driving simply goes poof! as friends carpool, and drivers bundle up errands into a single day.

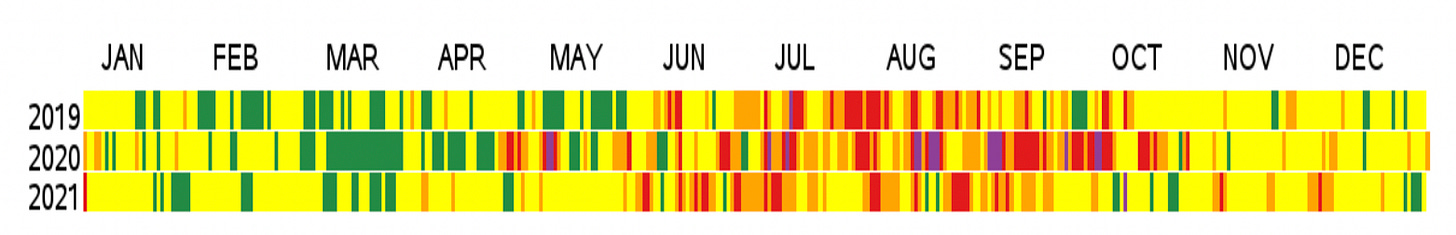

The pandemic year cleared the skies in Los Angeles to everyone’s delight. So why haven’t Angelenos taken any action to make clean skies a common goal? This is what’s known as a collective action problem. During the pandemic, most individuals marveled at the clear views of local mountains and reflected on a 70 year smog problem that made LA infamous. But when traffic started moving again, those same individuals and their personal travel needs came into conflict with “clean skies” as a group aspiration. Typically this problem is solved through public policy. But here too there’s a political action barrier in that the risks are too high for any elected officeholder to start a fight with car owners. You can literally see the mark of the pandemic on LA Basin emissions in the first half of 2020 in this DOE chart of daily AQI values. Also note the seasonal pattern, which sees LA County’s AQI index reach its worst levels during summer.

The American solution to this collective action problem is to always introduce a new system, like electric vehicles or in this case new transit options, without taxing the old system out of existence. This in itself is not a crazy approach, and at first glance looks clever. But after thirty years of LA Metro construction you would think it’s finally time to nudge car drivers towards fewer miles driven. Hence, a day charge for drivers is long overdue.

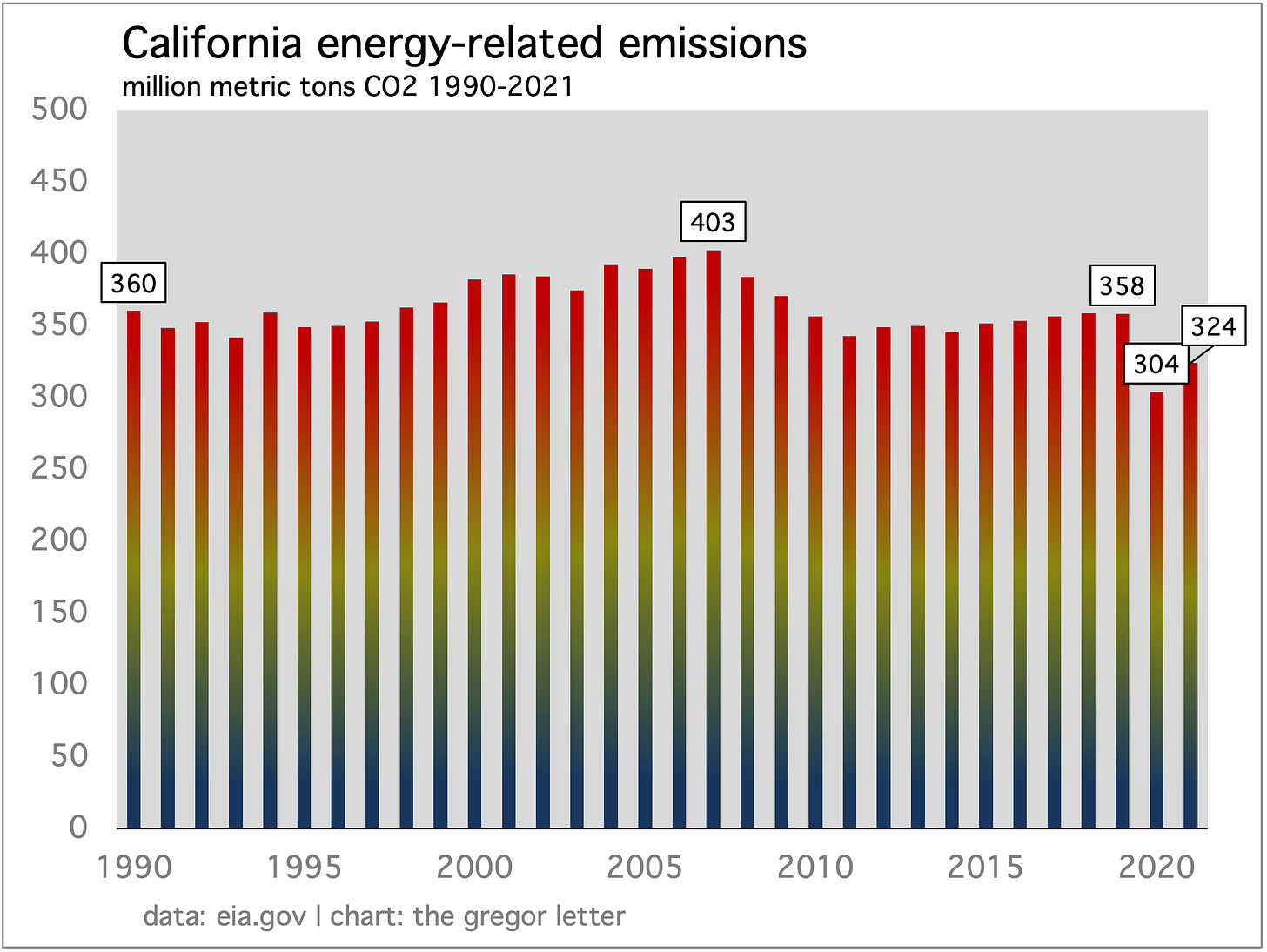

California’s total emissions took one step down after the great recession, and managed to suppress further growth through the big buildout of renewable power. Since 2010, California has been the US leader in solar deployment (an unassailable position that’s only just now being handed off to newcomers like Texas). This helped restrain emissions growth, offsetting stubbornly high emissions from transportation. And then of course, the pandemic happened.

Notice the profound drop during the pandemic year in energy related emissions. There is only one sector that can perform such a feat and that’s transportation: everything from trucks and buses to air travel. That 15% drop from 2019 to 2020 is the kind of rapid change the state could realize, if it chose. But that would require an attack on existing vehicles. Instead, we are on a far slower path. And while EV will eventually deliver those declines, America’s transportation policy failure means these declines won’t meaningfully roll out at a more rapid rate until next decade.

California’s total emissions decline from the high points of 2005-2007 is comparable to the declines Europe has achieved during the same period. California’s emissions are down roughly 20% from peak and Europe is down 25% from peak. (We have in hand 2022 data for Europe, but do not as yet have 2022 data from California). This should be unsurprising: California is America’s leading edge economy, and is therefore correctly adopting cleaner, cheaper, more efficient energy. Europe, however, is on pace to outdistance California from this point forward, because the continent is taking strong action against existing vehicles.

And to make this point more plain, nearly all other US states are far, far behind California in EV adoption. So in the same way California’s transportation sector was a long term drag on the state’s ability to lower emissions, the same will be true for the US as a whole.

You are reading Part I of a series on energy transition progress in California. The next installment will publish Monday, 4 December as part of a double-publication cycle of The Gregor Letter.

China is currently the world leader in building out new nuclear power. But at the same time, China is even more aggressively building out new solar. This is not supposed to happen, according to the zero-sum analysts who maintain that every unit of capital spent on one technology means less capital for the other. Whether this is just an intuition, or not, it’s wrong. Were solar still in its infancy there could be some well justified concern that the technology is killed in the crib, starved of capital that is otherwise going to nuclear. Actual history is the exact opposite. Solar did get its start on the back of subsidies, but now booms globally from Taiwan to Texas. Meanwhile, global nuclear has stagnated for two decades.

Through the first ten months of this year, China has added 142.56 GW of new solar according to Yan Quin, of Oslo-based RefinitivCarbon. To put that in perspective, China during several months this year has deployed more new solar than India deployed in all of last year. While India is a terrible laggard in solar expansion and thus a weak example, it’s still impressive that China will build 10X the new solar capacity. Analysts as recently as this summer expected China to build 150 GW of new solar this year. But given the country has already reached above 142 GW, with two months to go, it’s way past time to lift that estimate. China will easily hit 160 GW before year end.

China meanwhile has 21 nuclear projects under construction. That’s a massive program that, again, has had no effect on the country’s insane solar growth (or its recent leap into offshore wind). Even the US, which has a shaky nuclear outlook at best, was able to complete the Vogtle project this year, finally, but this has also had no effect on booming solar. As The Gregor Letter has constantly pointed out, wind, solar, and storage are the faster, cheaper, and better solutions that the private market now wants. Nuclear is in its own universe, and requires government guarantees and support, and lives in a separate economic lane. Chart below from the IAEA.

Fears of a Trump return to the Presidency have stimulated conversation as to how, precisely, he might thwart energy transition. A recent effort from the Financial Times, however, reveals that understanding how energy transition is structured in the US is not well understood. Moreover, there are things a President can do, and there are things a President simply cannot do. Knowing the difference matters. For example the FT piece makes a lot of noise about a future President Trump putting the Inflation Reduction Act in the crosshairs. Uh huh. Sure. The IRA is not just settled legislation, but is very much underway, catalyzing myriad investments (along with the CHIPS Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill) in everything from batteries to metals to transmission lines and other manufacturing. Most importantly is that this capital is being dumped disproportionately into red states. Does anyone really think that Tim Scott (R) of South Carolina, or other Republican senators in the southeast where much of this activity is taking place, are going to repeal the IRA? Good luck with that. Put another way, do the journalists at the FT understand even the most basic facts of how power is distributed among executive, legislative and judicial branches?

The other fear, which is more reasonable, is that Trump could take executive action and thus damage federal agencies like the EPA, while also relaxing regulations on emissions. That’s true, and that’s a real concern. How do we know the contours of Trump risk falls mainly along these lines? Because this is how he did it in his first term. There was no attack on wind, solar, batteries or the tax incentives around these and EV adoption. Instead, Trump took to deregulation. Trump term: can’t get anything passed that he campaigned on from coal, to healthcare. Biden term: gets major legislation passed in first two years, all of which is now rolling down the track.

A final consideration: US oil production and natural gas production are at all time highs under Biden. What can Trump do? How can Trump favor oil and gas even more?

The probability of future rate hikes by the Federal Reserve has now been entirely wiped out, by the futures market. And it’s not just inflation that’s falling, but strength in the job market is now relaxing as well. While the latter development has put nervous persons back on recession watch, it has converted the risk of future rate hikes into future rate cuts. According to the CME’s FedWatch Tool, the first rate cut could now come as early as the 24 March, 2024 FOMC meeting.

The Odd Lots Podcast recently had a particularly good show covering the problems facing the US offshore wind industry. The themes which The Gregor Letter has highlighted are echoed here, especially with regards to the nascent supply chain, and the fact that we don’t possess enough specialized deployment ships. Quite obviously, one factor that’s a challenge to follow is the path of interest rates. But it seems likely now that rates are going to fall in the same surprising fashion that they rose, starting in late 2021.

—Gregor Macdonald