California Survey II

Monday 4 December 2023

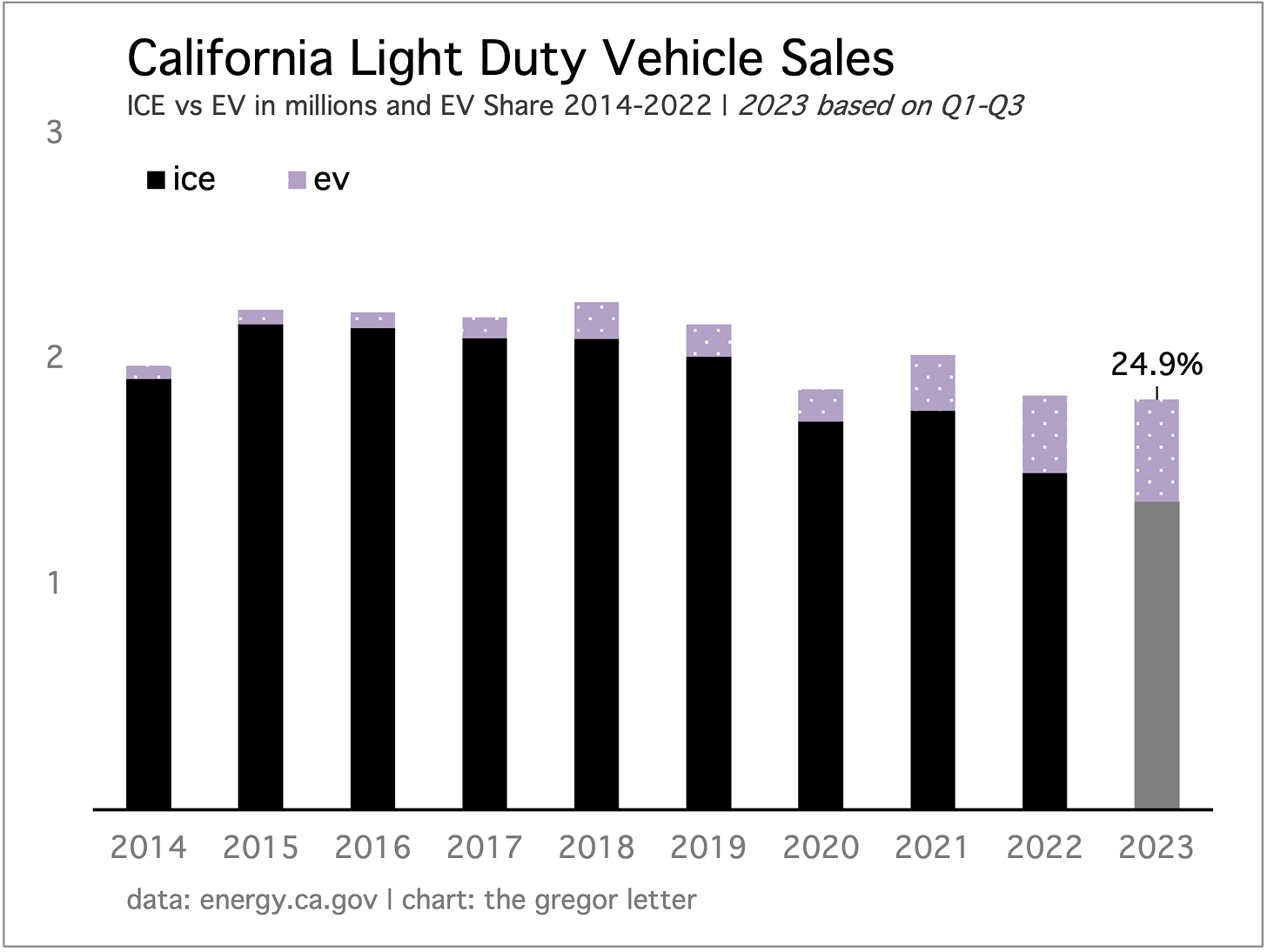

Sales of internal combustion engine vehicles in California have finally entered the collapse phase, down 37% from the high of 2.135 million set in 2015. The decline is accelerating. ICE sales as recently as 2019 were still above 2 million, but after the first 9 months of 2023 ICE are on course for 1.366 million annual sales, a 32% decline in just four years. California now joins China and Europe as plug-ins are poised to lift above 25% market share. At the current pace, they will reach 50% market share quickly, perhaps as soon as the end of 2025.

While the front end of EV adoption is insufficient to bend petrol demand downward, we are clearly now in the middle of the S curve for EV in California. Combined with higher petrol taxes and moderate fee disincentives for ICE (and stagnating population growth due to net outward migration) California’s gasoline demand is now in gentle decline. Here is the latest data which annualizes the first 8 months of 2023.

Is that an actual decline, that’s now beginning? Or another step-down, to a new stasis? A bit of both. The step-down clearly is a result of the pandemic and the work-from-home transition. But it’s also the case that the balance of EV to ICE sales reached a tipping point during the same period. In essence, total sales of vehicles fell, but EV sales did not. Here too we have a combination of factors swirling into the mix: inflation, higher interest rates, and higher car prices all leading to downward pressure on total sales. Let’s throw a pinch of the Osborne Effect into the equation too—because why not? What better time, during a pandemic when interest rates are rising, to say “you know what, why would I buy a new ICE vehicle now, when I’m working from home anyway, and when a flood of EV models and choice is finally going to arrive?”

The rate at which we decarbonize any system depends on how fast we deploy cleantech, and how fast the system itself is growing. The California light duty sales chart demonstrates the most ideal of outcomes, as EV sales are strong and growing while total sales flatline or decline some. Outrunning the system growth is therefore key to fast transition but it’s surprising how many analysts focus solely on EV sales, wind and solar growth, battery expansion, etc without paying at least as much attention to system growth. Wherever you have strong system growth, you immediately have a far more difficult transition challenge, and visa versa.

Is California a straightforward case, or a more complicated case of energy transition? Probably a bit of both. As the world’s largest sub-national economy (ranking fifth were it to stand alone) the answer matters. Los Angeles County alone contains a greater population than 40 US states. Half of all registered vehicles in the state are garaged in just the five large counties of Southern California. And given that the state accounts for nearly 13% of all the vehicles in the United States, that means roughly 6.5% of all US vehicles are in those five counties.

The state’s GDP dwarfs even its closest US competitors, weighing in at $3.6 trillion against Texas at $2.1 and New York at $1.9 trillion. The evolution of California GDP matters quite a bit because there’s a common intuition that growth will be either damaged or capped by energy transition. California is telling us no such erosion is forthcoming, especially given that the western world has increasingly transformed GDP towards intellectual and non-physical goods. California’s economy, in other words, mostly runs on electricity, not oil. Petroleum is a legacy product of the state’s history, beginning first with outright production in rich oilfields when the state population was small, and then subsequently as a giant oil consumer as the post-war highway system was erected.

Without the albatross of petrol dependency in transportation—say in a more balanced, European configuration between public transit and personal vehicle ownership—state emissions would by now be falling more rapidly. Like Europe, California’s grid increasingly runs on wind, solar, batteries, natural gas, and legacy nuclear power. Batteries in particular will boost clean electricity to even higher levels through a standard intertemporal strategy, as surplus wind and solar power is stored and released, over and over again. Everything you would want to see developing in the power sector is, in fact, happening.

After a spike in electricity demand last year on the back of heat waves, total California electricity demand has resumed its gentle downward motion, and thereby makes for an easy lay-up for combined wind and solar to expand market share. As a result, California is enjoying—and has been enjoying for years, since 2011/2012—rapid decarbonization as energy ex-wind+solar is steadily expunged from the system.

When grid level battery capacity gets large enough, it starts to function like generation. California’s battery capacity has grown by almost 10X in just four years, and at 6.8 GW and growing is now large enough to power 6.6 million homes for 4 hours. That’s incredible. This is in a state of 14.6 million total housing units. And battery growth remains impressive, to say the least. The State of California has created a new online dashboard to track battery growth and provide outlooks: to the current 6.6 GW the state expects another 1.9 GW to come online by year end.

If you have a large installed base of intermittent wind and solar, it starts to become economical to build more storage because the losses realized through curtailment become overly large. A fleet of batteries also improves the investment returns for owners of that electricity generation that would have previously been paid exactly $0.00 for the unused output. Almost in the same way that California lags other domains in taking more aggressive action on transportation emissions, it’s now stepping up and becoming a leader in storage. And that’s exciting, because we are going to see clean generation output reach its full potential.

Coda: the data gathering agencies are going to need to come up with a standard for measuring generation from grid batteries. One solution is to simply record the decline in curtailed generation, once storage capacity gets to scale. Another route would be to log consumed generation, as opposed to just generation. The Gregor Letter might prefer to see batteries have their own “generation” category, with an offsetting column that nets it back out, in acknowledgement that some other energy source or sources produced the electricity originally.

We should now place California in the same club of high renewable domains like the UK, and the Nordic countries. Imagine this picture: it’s 2026 and half the cars sold each year have a plug; 40% or more of state electricity comes from wind and solar; emissions are falling just a touch more rapidly; and the transit system of Los Angeles finally gains real traction. In this picture, the world is able to witness, with some clarity, that electricity indeed is the easiest sector to decarbonize, thus putting an even brighter spotlight on oil, and industrial uses of natural gas. At that point, California will then have to undertake the hard work around hydrogen and its applications. And, as always, it will still have to do something about the existing ICE cars. As stated in the first part of this series, Los Angeles is going to have to introduce a nominal day charge to drive in the city. Another strategy still largely unexplored: creating bikeway systems like Denver, or adopting bike friendly road infrastructure like Amsterdam and Portland, Oregon. The Olympics arrive in 2028. Now is the time.

Oil continues to weaken despite the threat of more OPEC cuts because the market correctly understands this just moves output over to the spare capacity column. Just to reiterate some key views expressed here at the letter over the past several years. 1. There was never any environmentalist-led destruction of global oil supply either around the world, or in the United States. 2. The US president like all previous presidents has exerted no negative influence on oil supply, as testified to by the US reaching all time highs yet again in production of both crude oil, and liquids. 3. There was never a supply problem globally, outside of a war and sanctions against Russia, combined with the usual short-term demand pressure that always accompanies economic recoveries. Even after the great recession, oil prices soared again to $100 a barrel not long after the crisis. 4. OPEC spare capacity is well above long term averages and will go even higher! 5. Oil and gas were terrible investments for a decade, had a two year reprieve, and if you were young and inexperienced you mistook that interlude as a new, investible upcycle necessary to meet a world of high growing oil demand. Sorry. It was a trade, not an investment.

Nothing about the pandemic altered the long-term disinflationary pressures that have been building for thirty years. There is no de-globalization. There is no regime change or structural change in the world’s workforce that would create a “new era of higher inflation.” The developed world is not de-industrializing either. Hearing these notions ticked off is a reminder that the past 2-3 years have hatched a bunch of very bad ideas that are curiously attractive—shiny baubles that captured the imagination of thinkers during a time of disruption. It is deeply ironic for example that, until 2019, the tributaries of long term disinflation were well known and accepted, and now the advent of AI is still not accepted much as an obvious and immediate productivity revolution. Too funny. By the way, the yield on the global benchmark 10 Year US Treasury is down 75 basis points from 5.00% to 4.25% in less than 6 weeks. The Fed’s not cutting yet, but the market sure is!

The Gregor Letter has registered a new domain, coldeye.earth, in anticipation of making a name change. The pairing of cold and eye comes from Yeats’ poem Under Ben Bulben. Now that the first wave of energy transition is over, it’s going to be more important than ever to “cast a cold eye” on developments, always vigilant in the face of unjustified pessimism, and optimism.

—Gregor Macdonald