Car Talk

Monday 21 October 2019

A profound change in the future of cars began to unfold in China last year. The trajectory shift may have happened so suddenly, however, that markets and the public have not fully processed the implications. There’s a term for this phenomenon. Cognitive conservatism describes our tendency to insufficiently revise our beliefs, when presented with new information. Time itself tends to cure this condition, but, when facing a system as large as the global vehicle market, new information coming through may be too unwieldy to process.

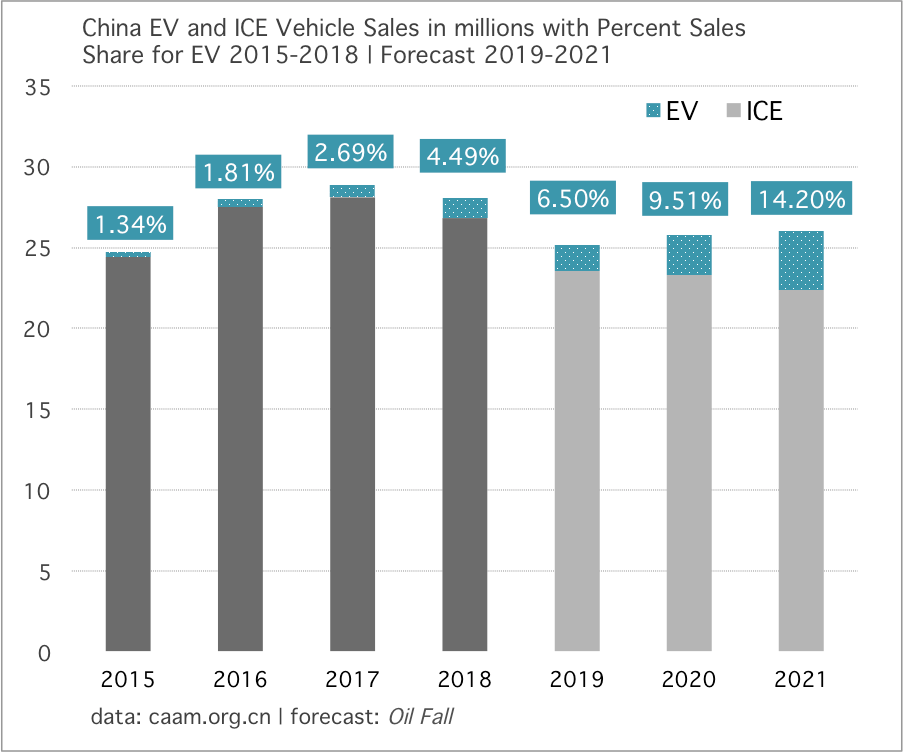

Start here: sales of vehicles powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE) are on course to fall by over 4.5 million units from a peak of 28.1 million in 2017 to 23.5 million units this year. That’s just astounding. Were this happening 20 years ago, we’d know that China had either entered, or, was close to a recession. And while it’s true the current trade-influenced slowdown in China has hit growth pretty hard, the concurrent ascent of electric vehicles has helped greatly in cushioning the market’s decline. For, as ICE vehicles are on course to fall 16% from the 2017 peak, the total car market in the same period is on course to fall 12.8%. The difference between the two, equal to about 2.9 million EV units, is due to the rollout of electric vehicles.

Here’s where cognitive conservatism comes into play. If you have a 28 million unit market, and a new technology enters and takes a 2.7% share (2017), then a 4.5% share (2018), and is on course to take a 6.5% share (2019) you should begin to have confidence there’s no regression coming, no imminent reversion to the old technology. And in the case of China, we can legitimately assert the substitution effect is in full swing, because China’s EV industry has largely produced mini, and super-mini EV that are quite affordable, and have been adopted quickly in China’s 2nd and 3rd tier cities.

(The Pickman EV pick-up truck, from China’s Kaiyun Motors)

Using a conservative forecast, in which the total market after its steep fall stabilizes over the next two years, ICE vehicle sales are likely to drift down towards 22 million units by 2021—and I would conjecture there will be another round of steep falls heading into 2025 as price parity for EV spreads through the Chinese market. The data shown here is both for passenger and commercial vehicles; and, importantly we know that EV adoption in buses, and fleets is actually moving even faster in China.

Here is the same chart, but with EV included. Again, please note the conservative forecast. I project that after a peak and steep decline, total car market growth flattens out for the next two years around 25 million units, as EV take an increasing market share while ICE continue their retreat. This pattern is oft-repeated in a number of systems currently, most notably in US electricity for example, where system growth has flattened as wind+solar gobbles up market share. The substitution effect is relentless. As I laid out in Oil Fall, by the time global vehicle markets stabilize and recover early next decade, it will be too late for ICE.

The data for China car markets statistics comes directly from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM). And, it is confirmed by various media and industry outlets, from a Shanghai Daily digital publication called Shine, to an industry publication called MarkLines. But it is not always easy to interact with the CAAM website, which is often down, or has URL problems. Here’s a cool thing however: I’ve discovered the full CAAM data release can be pulled through the WeChat app each month, using their news notification service. Here’s what the current release looks like, and if you are using a Chrome browser, you should get a prompt to translate to English, or it may automatically convert for you.

The bottom line: the entire Chinese car market, both passenger and commercial, is down 10.3% through the first 9 months of 2019. The EV market, which includes all plug-ins and hybrids—what China refers to as NEV—is up just 20.8% through the same period. These figures are reflected in the charts presented today—but, with one adjustment on my part. I’m projecting that NEV actually finish the year up 30% because Q4 tends to be the strongest quarter for EV in most markets, and in China. So be warned: I could be wrong about that adjustment, and NEV could finish the year closer to the present growth rate of 21%. Would that meaningfully change the projected EV market share for this year, of 6.5%, and, by how much? Answer: by a half percentage point. Ergo, if the total market remains on course for a 10.3% decline, and NEV only grow by 21%, then their market share this year will come in not at 6.5%, but at 6.0%.

The conclusion we should draw, however, is that a well established adoption curve is underway for EV in China. There is no going back. The EV drivetrain is superior in every way, and the learning rate is pressing onward. ICE growth is over in the world’s largest vehicle market, and China’s OEMs are far ahead of US carmakers in tooling and shaping new offerings. And soon, China EV will appear globally. Chinese OEM Chery is on the verge of entering the European market, with a number of offerings set to appear in the world’s great EV wonderland: Norway. As for a recently common retort that China’s car industry or EV industry is in a bubble, I say: who cares? Nothing could be more normal than a flood of entrants chasing a new technology, with many fated to never see the promised land.

The global auto industry has a large footprint, and accounts for about 5.7% of global industrial output according to the October World Economic Outlook from the IMF. It’s beyond my current scope to assess how the transition to EV will affect myriad commodities, supply chains, and ancillary services but I am willing to venture the impact on auto-dependent real estate, repair shops, and related infrastructure will be substantial. The ICE domain is very much about oil, grease, petroleum, a greater number of moving parts, gasoline supply that must be ferried by truck to filling stations, and lots of technology and parts related to emissions, and exhaust. On a macro level, the ICE domain is also about the global shipping of oil, and all the import, export and refining infrastructure related to that task. The EV domain is of course about electricity, charging infrastructure, fewer parts, and the absence of all things petroleum related. Petroleum use will have a very long tail of dependency and use, but zero growth, followed by steady decline.

What’s also clear is that our current global slowdown, composed of several factors from a trade war to the maturation of the Chinese economy, has also merged with the challenges of an auto sector that must contend with fewer sales overall, and, a drivetrain transition. The drag on growth is quite real.

Hat tip to Adam Tooze for flagging this recent IMF research, and the more direct link to the October release from the IMF can be found here, via Google Books. The other chart from the referring page in the link also says alot about which economies are most deeply affected by the auto market slowdown. No surprise: China and the EU.

At the start of 2019, The Gregor Letter forecasted that global oil demand growth would be closer to 0.7 mbpd, half the IEA forecast of 1.4 mbpd. The IEA, which has a strong track record in recent years of over-estimating global oil demand has now pulled back their forecast to 1.0 mbpd. As usual, the IEA is hanging on to a second-half 2019 growth story that’s not only failing to materialize, but, which can’t possibly make up lost ground. Quite ridiculously, IEA has acknowledges first half 2019 growth came in at just 0.4 mbpd. Thus, making a mockery of their full year call for 1.0 mbpd. But that’s ok. The oil futures market has long since figured this one out, and, we should finish out 2019 well below 1.0 mbpd of growth, right around 0.6-0.8 mbpd.

Car ownership in Paris has fallen dramatically since 2001, as bike ownership soared. 60% of households once owned a car in France’s largest city, and now just 35% do, as Paris has concurrently risen through the ranks from 17th to 8th most bike friendly city. The most useful takeaway from the shift is not that Paris, or even France as a whole, will bend the curve of global vehicle ownership. Rather, it’s a leading edge story, as cities from Barcelona to New York increasingly experiment with removing cars from key thoroughfares or districts, while also introducing congestion charging. Paris, like Detroit, Los Angeles, Wellington, and London and others have also put streets on road diets—slowing traffic, layering in bike lanes, and planting trees or other greenery to signal the change.

The reason to take this trend seriously is that contra the fears of merchants, most data now coming through suggests that road diets make streets more inviting to pedestrians, cyclists, and families and this now boosts, rather than dents, commercial activity. In the same way inner-city highway removal was once controversial, but is now widely accepted as a good strategy, the same cultural conclusion will wash over cities as they continue to roll back a century of over-broad freedom for cars.

(The Georges Pompidou riverside motorway, transformed for pedestrians, 2016)

The IEA recently analyzed the global trend towards SUV models, showing the popularity of these models raised oil consumption and emissions over the past decade. There is some dispute, however, as to how to account for the SUV role. For example, if you tally SUV purchases and assume buyers would not have purchased any vehicle whatsoever, you’d obviously arrive at a much larger impact from the trend. Perhaps as much as the entire 3.3 mbpd of growth from the passenger car sector, between 2010 and 2018, as the IEA reports. At Bloomberg, however, Nathaniel Bullard showed that the actual increase is closer to 0.5 mbpd, if one imputes to every SUV purchase that a sale of an ICE vehicle would have occurred regardless.

I have an entirely different take on this development, which doesn’t focus on adjudicating between the two separate analyses. (In case you’re interested, the Bullard take is much closer to the truth.) Rather, when I see this claim about SUV suddenly appearing here at the end of the decade it strikes me as a flag-planting exercise, one that typically appears at the end rather than the beginning of a trend. We know, for example, that the global auto industry will inevitably produce electric SUV and pick-up trucks for the passenger vehicle market—and yes, ones that are affordable. Moreover, SUV more typically refer to crossovers—vehicles that have roughly the same wheelbase as sedans (and sometimes shorter) but whose design accommodates 4-doors and some version of a boxy rear, or hatch-back. Kia and Hyundai are already producing 100% electric crossovers, and Volkswagen and other makers will soon follow.

There is no dispute that the advent of SUV have been quite a problem really for two decades now. At one time, the Chevy Suburban was rarer outside of the US southwest, for example. But by 2010 very large, truck-like SUV very much in the Suburban tradition were everywhere, from the streets of Los Angeles to the suburbs of Boston. This trend will not survive the rollout of electrics, however. And, we are on the cusp of the EV decade.

California’s vehicle market is down 5.6% through the first 6 months of 2019. The decline far outpaces the national decline, currently fluctuating but down about 2%. Importantly, however, is that EV took 7.9% of the California market last year, and are on course to take a full 10% this year. Although EV sales growth in California is far, far weaker this year—up only 20% versus last year’s torrid growth of 60%—the new technology is feasting on the overall market decline. A plausible forecast looks something like this:

Overall, 2019 has been an even weaker year of growth for EV in the United States, as national sales will likely only advance by single digits, perhaps as little as 3-5%. We will soon need to assess, however, the prospect for greater consumer choice in 2020, as the US market remains overly reliant on Tesla sales. All this said, EV in China, Europe, the US, and smaller markets like the UK and California are performing admirably against a global auto slowdown. Whether the economy weakens in the US, however, remains a key uncertainty, and should that happen in 2020 forecasts for EV sales, and especially ICE sales, would require significant adjustment.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.