Clean Britannia

Monday 19 September 2022

If you tend to think of California as the world’s fast-moving edge economy, especially with regards to wind, solar, and EV adoption, then the UK merits inclusion in the same category. That’s right. The UK is carving out a new fate for itself, as a singularly clean, green land. To be sure, wind generation faltered notably last year. But that is a brief hiccup to the country’s ongoing leadership in decarbonization. Coal consumption and oil consumption meanwhile have been in a well defined retreat for two decades now, leading to a kind of superdecline in UK emissions.

Let’s take a look at the way wind and solar swiftly entered the UK’s power system over the past decade. Progress here conforms entirely to growth patterns seen in other technology adoption, in which it seemingly takes forever to gain market share until the 5% level, after which the big breakout occurs. This particular crossover point was reached in 2012, when combined wind and solar first crested above 5% of the country’s total power generation. By 2020, they had moved above a 28% share, before falling back last year during a long lull in the region’s wind supply. Note: while solar is starting to grow more rapidly in the UK, the country’s massive offshore wind farms dominate the contribution to the grid, and the wind/solar share mix in 2021 stood at roughly 85/15.

The loser in this equation is, of course, coal. Historically speaking this is quite remarkable. In the birthplace of the industrial revolution, where coal’s powerful energy density once transformed British wages, output, and economic power, coal is now effectively zeroed out. If readers are not familiar with the heat unit here, the exajoule (EJ), let’s compare: the UK’s 2021 consumption at 0.21 EJ is just 1/10th of Germany’s usage in the same year of 2.12 EJ, and roughly 1/50th of Europe’s usage of 10.01 EJ. Another metric: as recently as 2012 coal accounted for 40% of the UK’s power generation. Just eight years later, in 2020, coal-fired power generation had dropped to 1.8%. That’s not a decline. That’s a collapse.

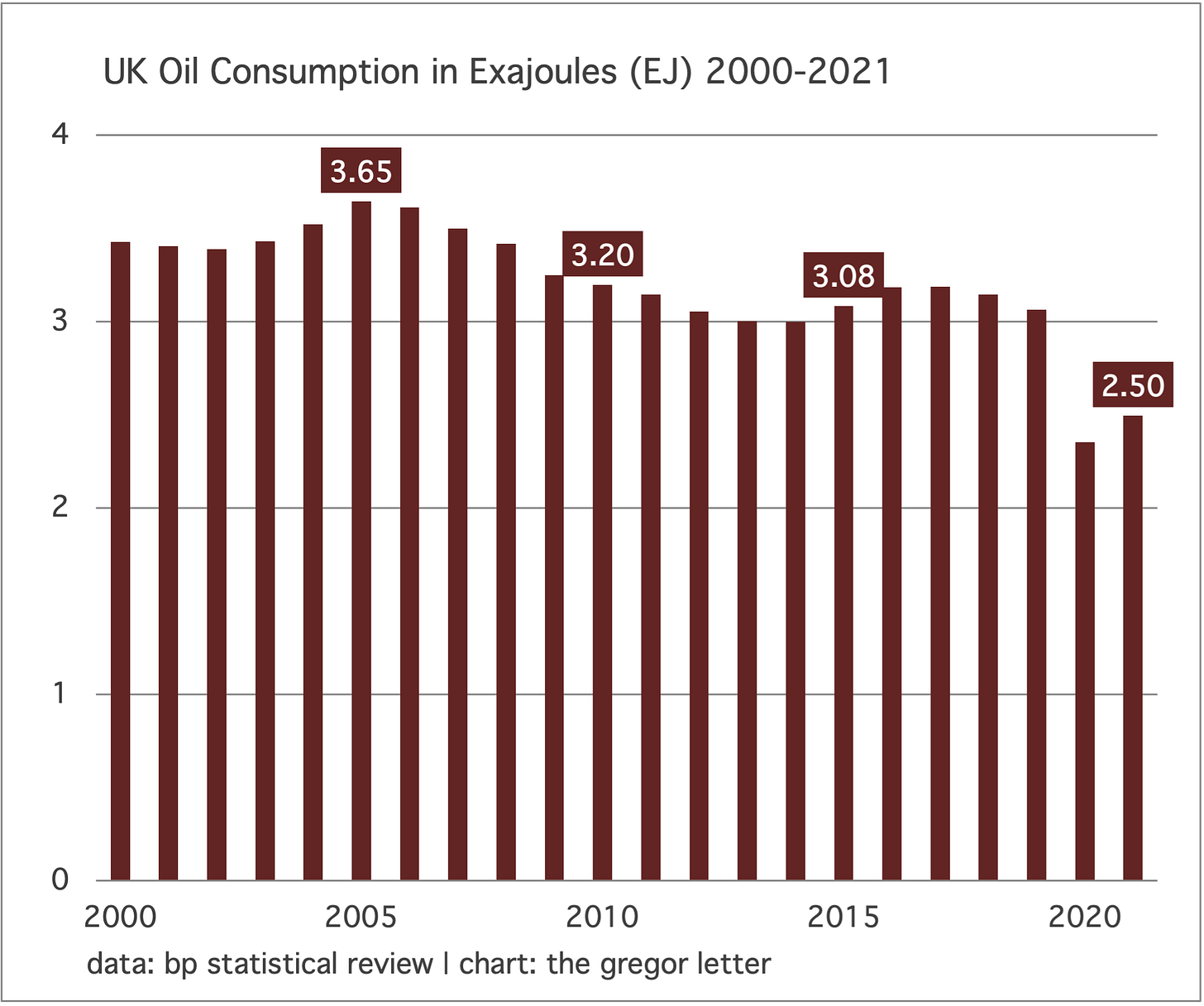

In oil, the UK has largely tracked the long term decline of European oil consumption since the 2005 peak. It’s worth reminding, 2005 was the year oil consumption peaked not only in the UK, but also in the United States, and the OECD as a whole. So, viewed through this lens, the UK’s efforts to step off the oil train conforms to the performance of its peers. Or does it? While US oil consumption did peak in 2005, its demand profile since then has roughly oscillated around a flat line. But while US oil consumption is down 8.9% from 2005-2021, the UK’s oil consumption is down 31.5% in the same period.

We must be cautious, however. We are still in the shadow of the pandemic which disrupted just about everything in the world—including every data series! The US, Europe, and the OECD as a whole are seeing a continued shift in work related travel patterns—everything from business travel to daily commuting. If, say, you have a view that mean reversion will eventually reconstruct this demand entirely, then you might look askance at the UK’s 2021 oil consumption level.

But you might also want to consider that EV adoption in the UK has also swept in like a gale from the North Sea. Here once again the UK is keeping pace with its counterpart, California. Or rather, more than keeping pace. Combined UK plug-in sales in 2021 achieved an 18.7% share of the car market. And this year, plug-ins have reached a 20% share. Plug-ins in California reached 12.8% in 2021, and are on course to reach a 17.5% share this year.

We record these dramatic changes best through the UK’s emissions from energy consumption. And the decline has been dramatic—starting from long before the pandemic.

Where the UK is also leading, and will need to continue leading, is in the deployment of storage. While a growing fleet of EV can certainly help with demand side management of a grid that fluctuates with powerful yet volatile wind power, only battery banks (and lots of them) can effectively capture surplus output that flows overnight from Britain’s burgeoning offshore wind farms. Yes, the emerging wave of home batteries will help. Yes, the ascent of UK charging stations which also contain a big battery will help. Institutions and government properties will also likely install batteries. And all of these will load up with overnight, surplus power. But the UK will still need grid storage to capitalize on its ongoing wind power investment. That’s how you maximize the value, and the return, on renewables. Good news: the UK is the European leader in building and planning to build more storage.

But there’s another way to maximize the ongoing investment in the UK’s renewables base: by building some new nuclear. And also, by extending the life of existing nuclear power. Here, the United States experience is instructive. The US has recently figured out that every time an aging nuclear power station retires, progress in total clean power deployment suffers a setback. And that’s especially bad given that in the US, as in the entire world, generation from nuclear power has been hugging a flatline for decades. The results of having allowed so many nuclear plants to retire, and the failure to build enough new nuclear, can be seen below. Look at wind and solar, coming along beautifully. And yet, nuclear’s flatline ceded a huge chunk of potential clean energy growth to natural gas. This is happening globally, and it’s going to continue happening.

The UK should be congratulated. It has crushed coal with fast moving wind power. It’s electrifying transport, not just cars but buses and commercial vehicles. And it’s now beginning to add more solar, cleaning up its grid further, which means all electric transport gets cleaner too. And the UK is moving quickly. Partly, that’s due to the intrinsic qualities of both wind and solar. Indeed, the sheer speed of both technologies, solar on the global level especially, has profound impacts not just for climate but for the investment equation, increasing return-on-investment by compressing completion timelines. The Gregor Letter more recently devoted an issue to this unique quality in The Speed of Solar.

However, a problem remains. Even if wind and solar maintain, or better yet, increase their deployment speed, it’s still not adequate. Global natural gas adoption is soaring and the reasons are straightforward: as coal dies globally in power generation, wind+solar are not the only opportunists feasting on its carcass. Natural gas is thriving too on coal’s decline, building path dependency. And it’s got momentum. To stop it, wind, solar, and storage (WSS) need a companion technology that would effectively blot out natural gas’s future growth prospects. A technology that fully cedes the leadership position to WSS, but comes online, wherever it’s able. At the moment, despite being slow, expensive, and weighed down by steep social hurdles, that technology is nuclear. 🇬🇧

The US Federal Reserve will probably make a policy mistake, this coming week. To review, as the housing market and inflation began to lift last year, many reasonable people began to speak out, baffled that the Fed was still buying mortgages, seemingly impervious to the fact this was long past necessary to support housing during the pandemic. We are now in the mirror of that situation, as the Fed has allowed itself to overreact to lagging inflation data, as just about every measure of inflation in the pipeline globally turns downward. Worse, Fed communication itself has become volatile, and all over the map. They said they were concerned about energy prices. When energy prices came down, they said they were concerned about goods prices. When supply chains improved they said they were concerned about services inflation. They’ve said they care most about PCE, no wait, CPI, no, sorry, month-over-month PCE and CPI. Each week sees a Fed governor or FOMC member contradicting others. Some say “they didn’t like to see the stock market going up.” Others say “they have to be careful about moving too fast.” Alot of the talk is casual and loose, and it does not inspire confidence.

One paradox The Gregor Letter has previously spoken to is the risk, not entirely unjustified, that if the Fed chairman or other FOMC members merely acknowledge that commodity prices have crashed, gasoline has fallen, housing has cracked, and the global economy is weak, then this admission will ignite animal spirits in the stock market, and revive inflation. To be sure, it has a logic to it. But it seems silly all the same. Inflation has very obviously peaked. Even last week’s CPI report, which disappointed in the core, month-over-month reading, did not rebut this notion. The sightlines are pretty clear now: housing has turned down strongly, and global demand is terrible. Input prices reflect these emerging realities, and all that’s left is the same message to arrive in the jobs market.

So the Fed, which is expected to do a third rate increase of .75 basis points this week, is probably going to look back on the third week of September as the moment when, for the sake of a short term display of power, they bought themselves yet another recession, during which they’ll have to cut rates again, or worse, stimulate. The bond manager Jeffrey Gundlach recently spoke to this tragic if not stupid cycle, repeated over the past two decades. His suggestion: how about slowing down the rate hikes now, letting them work through the system, so that maybe, just maybe, the Fed could see a sustained period in which it doesn’t have to cut rates, doesn’t have to undertake quantitative easing, and can actually maintain a Fed funds rate somewhere above zero? We shall see.

Could fast deployment of clean, cheap energy paradoxically lead to increased global emissions? The idea seems heretical, but was observed in the 19th century by the economist William Stanley Jevons. Known as Jevons Paradox, the idea is simple enough to understand: new energy sources are adopted because they are cheaper or more powerful per unit, compared to the previous energy resource. This leads to greater efficiency and unlocks wealth, a kind of windfall for society as a whole. That windfall is then translated into increased consumption of resources. Also known as the rebound effect, it’s often helpful to think of this phenomenon as an energy tax cut. And it then leads, as Jevons observed, to more demand for energy.

The counterargument today is that increased demand for energy can be met by more clean energy, not more fossil fuels. That seems obvious, except in practice. For it’s not exactly clear, given that total global energy demand keeps rising, that the introduction of renewables has meaningfully suppressed growth in combustion. To be sure, it’s an easier case to make in developed regions like the US or Europe, for example, that wind and solar have obviously killed off coal growth, even if they’ve had to share new growth with natural gas. But globally, it’s harder to make the case. Coal’s rebound in 2021, which wiped out all the gains (demand declines) since coal peaked in 2014 should give us pause. Oil’s growth in the 21st century meanwhile has indeed slowed down. But natural gas has seen spectacular growth this decade.

One reasonable answer might offer a moderate concession to Jevons, while retaining the larger claim that efficiency gains realized through clean energy deployment will, in fact, simply lead to more clean energy deployment. For example, it’s certainly possible if not likely that in countries like China or India, which are still developing, that new sources of affordable clean energy may very well lead to a boost in growth, and greater energy consumption overall, because these economies are very much in the growth phase of their development cycle. In Europe and the US, however, it’s evident already that fossil fuel energy is in decline, that renewables are taking the market share, and no energy consumption rebound is taking place that neuters the contribution of wind and solar, or the ongoing project of electrification.

An interesting project to ponder, when musing over these questions is the soon to be completed Al Maktoum Solar Park in Dubai. When completed, the park should have a nameplate capacity of roughly 3 GW. That’s huge. Its capacity factor—the amount of output it can realize compared to its theoretically highest output—will also be insanely high because of its location. The question then becomes, does this clean electricity supply avoid the construction of coal, or natural gas capacity? In the near term, most certainly. But assuming it supports Dubai’s economy, would it then partly lead to broader economic growth? No doubt. And as long as that growth is fed by more clean energy, then we have one answer. But the U.A.E. is a developing state. And a fast growing one, that has come up the ranks to be the second largest economy in the region. Oil and gas demand are growing at a healthy clip. We shall see.

—Gregor Macdonald