Coal Case

Monday 9 August 2021

Global coal demand has finally started to move off its plateau, set originally during the peak of 2013-2014. But this took years to develop, and remains a warning for those who now expect oil demand to decline meaningfully in the near term. Significant policy and technology advances were required in several key regions to pull down global coal demand—that is, down hard enough to beat back the continued growth in Asia. That dynamic remains very much in play today, for coal. But in this framing, one can spy the pathway for how oil demand too might weaken more steadily. As the last letter laid out, global oil demand could indeed now enter a minor, gentle decline if the OECD pulls down hard enough on the lever to counter continued Asian growth.

Over a decade ago, it was possible to see the global coal market as one dominated by a handful of top users, or what could be called The Coal Seven: China, US, India, Japan, South Africa, Russia, and Germany. Using 2010 as a baseline, the spread among these was vast—with China and the US at 73.22 and 20.88 EJ of consumption, respectively, and Germany at just 3.23 EJ. Clearly, to move the needle on global coal consumption it was going to require either China or the US to make a dramatic change. And, it would also be necessary to constrain the growth of third place India, at 12.16 EJ of consumption.

In the charts below, China is given its own graph so that The Coal Seven ex-China can more clearly be illustrated, while also adhering to a zero-scaled y-axis.

So what happened? Three things happened. The main event occurred in the US, as natural gas and then renewables worked together to vigorously pound coal consumption down from 20.88 EJ in 2010 to 9.20 EJ last year. It’s important to note, however, that discretionary replacement of coal capacity played a far lesser role in this shift. Rather, it was a lucky coincidence that so much of America’s coal fleet entered the retirement window just as renewables crossed key affordability thresholds. Had much of the US coal fleet come into that window 10-15 years earlier, the US powergrid would have had to face a far more difficult challenge, as the fleet would have been newly composed with young, better running coal plants rather than the broken down and busted fleet that’s currently being swept away.

The second event occurred when Europe, with Germany in the lead, finally stepped off its own plateau and took Europe-wide consumption down from 15.34 to 9.4 EJ as of last year. Notice the math: the US cut its own demand by half, and Europe cut by nearly 40%, and now both are nearly identical in their annual consumption at 9.2 - 9.4 EJ.

Finally, the third event is more nuanced: India’s consumption grew, but not nearly as much as the coal industry expected or hoped, as the country began to head off its own growth starting mid decade. Yes, India’s demand grew by 5.38 EJ from 12.16 to 17.54 EJ in the 2010-2020 period. But the Europe-wide decline neutralized it fully. And in that seemingly small nugget, we have our story of the decade in coal: The last remaining hope for the coal industry was that India, with just 10-15% fewer people than China, would converge with China’s own coal story. Didn’t happen. Accordingly, this sharpened the tension to a contest between the top dogs, China and the US. And as we now know, the US shed such a large volume of demand (with still more to come) that it neutralized China’s growth.

While there is still upside risk to this view, owing in part to the hit all energy consumption took in 2020, coal’s prospects outside of China are grim. Indeed, even within China (and even if one takes the view that in strong economies that renewables don’t replace legacy consumption but merely add to it) the outlook for coal is poor. And now comes the kicker: you see, China’s own coal consumption reached its own plateau around 2014. So the bulk of the coal demand growth that occurred last decade in China actually took place prior to mid-decade. As the top world consumer, China’s peak became the world’s peak. And China’s plateau controls the world plateau—or at least, it did—until Europe, the US, and the slower growth in India landed, with impact.

The coal case remains enormously instructive, therefore, if we think about the puzzle pieces of global oil demand, and the various ways that demand could simply plateau for the rest of this decade, or, enter decline. To trigger a sustained decline, it will be necessary not merely for US oil demand to continue its decade-long flattening, or for the EU to press onward with its own healthy decline. This may seem obvious, but to produce a sustained decline, Asian demand will either 1. have to flatten, while moderate declines set in elsewhere, or 2. If still growing, will have to be offset by more pronounced declines elsewhere. Again, observe how dramatic the decline of coal was in the US, and still the world level demand mostly plateaued for years. Looking ahead there, if you see oil demand start to dramatically decline in a big region, like Europe, that alone will not get the global level to step off its own ledge.

Gold prices slumped hard as the economic recovery pressed onward, with strong and well-distributed job creation. Gold investors are not unlike other investors who persist in the belief the market will eventually agree with them when certain metrics and conditions are sufficiently met. But investors everywhere need periodic reminding that prices are social phenomena, not the robotic or calculated result of math equations. A popular phrase in the gold community for decades has held that “either you believe in magic, or math. And if you believe in math, buy gold.” What’s implied, but not said, in that phrase is the notion of commonly shared beliefs or values about debt, interest rates, growth, inflation, and policy. But what if: in the same way consensus has broken down in other social systems there are now fractures in markets too about valuation, and how to price all assets?

The Gregor Letter over the past year and a half has periodically addressed the price of gold because it’s been a useful proxy for the tension between slow growth and fast growth, and all the attendant conditions associated with those two regimes. The letter has offered the following, rather simple view: when growth prospects are poor, long duration assets like gold and long-term bonds thrive. When growth prospects are excellent, global capital will tend to invest or even chase human-created entities called corporations that try their best to exploit interplays of demand, supply, and technological advances.

Using this simple model, Friday’s quite strong jobs report was a retort to the recent strength in long-term treasury bonds, and by extension, the recent price strength in gold. The investment proposition is easy: if global growth is going to press onward for several years, a basket of stocks like Caterpillar, Google, Rio Tinto, Ford Motors, Honeywell, and JP Morgan will do better, and possibly even far better than gold.

What must have been particularly soul-crushing for gold investors was to witness the yellow metal, after a year long downtrend and a failed hopeful rally, fail once again just as real interest rates had turned even more deeply negative. To be fair, that metric has historically been supportive of gold prices and one can understand therefore using gold as the vehicle to play that dynamic. But doing so carries an assumption: that others in the market will agree with your terms.

It’s reasonable therefore to say that gold is undergoing a transition in its investor base. In the previous era, that base shared common opinions about levels of government debt, interest rates, and inflation. The new era is marked by heavier disagreement, even to the point that gold has at times thrived more durably under a regime of deflation, rather than inflation, as the metal turned its attention not to outright price inflation but reflationary monetary policy. Accordingly, we should be dutifully circumspect in relying further on gold as a price signal. And yes, we should be cautious also about the rather simple framing offered here, that gold reacts to stronger forward looking economic growth as Superman does, in proximity to kryptonite.

S&P 500 earnings estimates continue their amazing advance for this year, and next. Given that S&P 500 earnings stood at $162.97 in 2019, the projection that 2021 earnings would not just exceed, but well exceed those levels seemed like a dim prospect as recently as early this year. But 2021 earnings have now advanced to $200.53, while next year’s earnings (what matters most) have moved to $221.59, according to the latest estimates. The US stock market’s current posture is typical of a post-crisis phase, in which the painful memories of a crash remain vivid for most investors. This is largely how the market can steadily march higher, as it climbs a wall of skepticism. The current index level, around 4400, is also not unusual as it carries once again the 20 multiple that has been typical in recent years.

• News briefs. • The BIB (Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill) is about to pass congress, but it’s just a warm-up to the far bigger package that will pass through reconciliation. Worth noting however: as “small” as the BIB may be, it’s heavily weighted towards transportation. • Form Energy, a Massachusetts based battery start-up, thrilled the power sector with the promise of a grid level battery that could discharge for 100 hours. The company is using an iron-air process, and if its price targets are realized, the battery could be quite disruptive. • Relatedly, Jennifer Granholm’s energy department has maintained an aggressive pace, and announced its second Earthshot initiative, this time for LDES. This follows the DOE’s Earthshot for hydrogen, announced in June. • Back in the world of vehicle batteries, a number of experts are increasingly pointing out that innovation and improvements to standard lithium-ion continue to chug along at a good pace. The latest effort surrounds increasing the lifespan of the battery pack. • DHL is adding electric cargo planes to its fleet. The opportunity here is in short-haul flights that are potentially more economic than transport by land. Indeed, more broadly, electrified aviation is likely to concentrate at the “small” end of the market for a while. • Wildfires raced across the coastal Mediterranean region, with Turkey and Greece particularly hard hit. Photographer Mishka Bochkaryov captured a beach scene in Turkey, posted at his Instagram account. •

A Bloomberg news story declared the era of cheap natural gas was now over. But the arguments offered for such a grand claim seem more like extensions of the demand growth we’ve seen the past decade, seasoned with the view there would be a supply problem soon. Using price as a supporting argument, the authors measured natural gas’s price advance from the lows reached during the pandemic panic. Well, that’s an old baseline no-no. (Imagine doing the same with oil, from its negative price prints last year.)

There is no argument that natural gas demand growth has been robust this past decade. The US has been a leader in this regard. BP Statistical Review data shows the 10 year trailing average growth rate globally clocks in at 2.9%, and that’s including the pandemic year, 2020. So yes, we have all been aware of the sector’s success.

The problem in the argument comes both on the supply side, and, on the future demand side in a world that is now seeing an accelerated rate of wind, solar + storage deployment. On the supply side, a massive expansion of natural gas into the US power system did not move price much at all for a decade. The reason? North America, not just the US but Canada in particular, has absolutely mind-blowing volumes of economically recoverable natural gas reserves. If higher prices are sustained for any length of time, we know exactly what the industry will do with those reserves.

But the more surprising aspects of the argument raise a question: why declare the era of cheap natural gas over, now, today, this year? Why now? The time to have made that declaration was years ago, as LNG infrastructure blossomed, and coal retirements in Europe and the US did indeed open a large gateway for NG. Now, we have wind, solar + storage stomping through the powergrids of China, the US, Europe and in the developing world. This is perhaps the very worst time to make such a declaration.

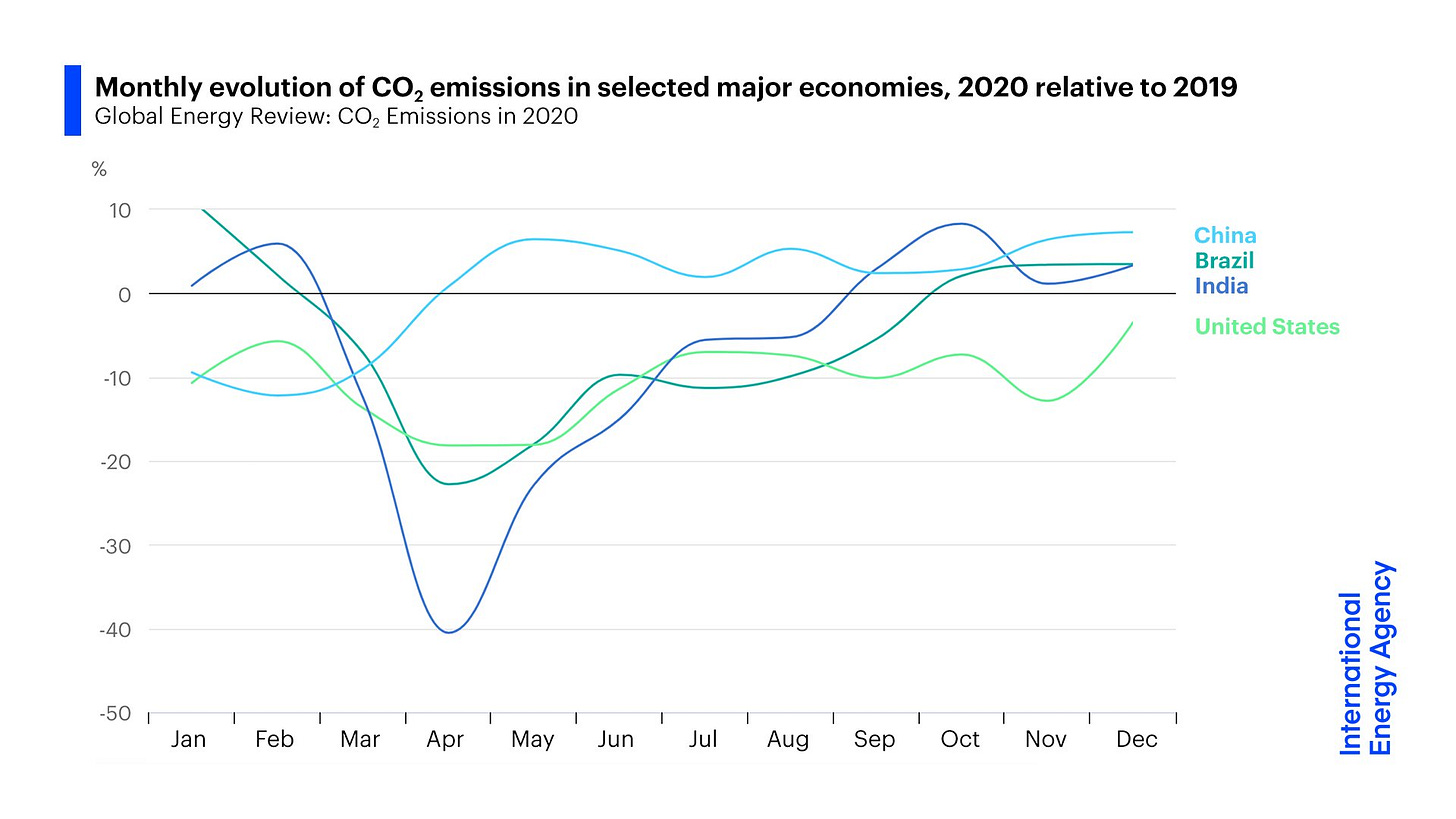

Despite the recovery in global emissions, both Europe and the US have lagged the developing world in the return of output. Mostly, that’s due to lower oil consumption, and the way in which changes to commuting landed hard on the use of cars. As mentioned in the the last letter, developed world professions align much better with a transition to Work From Home. And even as the bulk of OECD workers do return to the workplace, a large percentage will likely transition to a mix of locales. That alone will place pressure on OECD oil consumption for at least another year, and perhaps permanently.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.