Cold Eye

25 December 2023

Coverage of the energy transition should be adjusted, now that the first great turn of the wheel is behind us. The Gregor Letter generally identifies 2010 as the baseline year of global transition. Antecedent technology development in the decades prior certainly matters, but 2010 remains the best starting point to measure actual adoption. For example, if you are applying honest analysis of our progress so far, you wouldn’t drown the data in the tiny forward movement of renewables since the year 2000, or 1990. Equally, if you’re defending energy transition’s progress against an honest critic you’ve got to be sober about how much has, and has not, been accomplished since 2010; and you’ve got to grapple with the actual transition rate.

• Over a decade ago, energy transition as a concept was somewhat arcane but now is quite clearly part of common discourse. Similarly, the business press and traditional media now regularly include facts and developments around decarbonization as part of macroeconomic coverage.

• Combined wind+solar provided 380 TWh of power globally in 2010 but provided 3427 TWh by last year, advancing from a 1.75% share to 11.75% share of total generation. Students of growth will understand the implications now that the breakout level of 5% share is behind us. Meanwhile, select domains like California, Texas, and the EU have seen clean power reach even higher share, over 30% share in those two US states, and over 22% in the EU. Wind and solar are the undisputed leaders of new power generation capacity, beating everything else in cost terms and speed to operation. Storage will follow.

• Fossil fuel consumption is already near or at peak, and will definitively peak this decade. However, that we are not yet near actual fossil fuel declines globally is itself a marker for the next phase of energy transition. Back in 2010, the great game in analysis was forecasting peaks, trying to discern when they’d arrive. That game is now over, and has given way to a characteristic of the middle phase of energy transition: trying to forecast declines, which will prove hard to achieve.

• EV sales share globally was scant in 2010 but will reach at least 15% this year, if not a touch higher. Most countries are preparing to align policies with the EV drivetrain, and US automakers are now universally understood to have fallen far behind. Along with the wider adoption of electrics in buses, trucks, and the 2-3 wheeler markets of Asia, vehicles with a plug are already avoiding nearly 2 million barrels a day of oil demand, according to BNEF.

• Industrial revolutions attack the easiest problems first and energy transition is no different, with the first wave having profoundly affected global electricity, halting global coal growth (in power), and now spreading its impact to storage markets. The middle phase of transition will see work begin on the tougher problems, like coal and natural gas use in industry. Hydrogen developments are a key example, as both Europe and now the US have undertaken serious, active policy proposals to get H2 production underway, and to ensure supply arises first near demand centers.

• Criticism of energy transition has moved from the view over a decade ago that “it’s all a stupid fantasy” to today’s complaint that “it’s moving too fast, and is too disruptive.”

The Gregor Letter has been making adjustments to coverage all year, in light of the current juncture. Attention to oil has been greatly downgraded, now that global oil consumption has reached a plateau. And the letter rarely addresses coal. To put a fine point on this, the press generates stories endlessly about OPEC policy, tiny fluctuations in petrol demand, and pricing. But these stories don’t tell us anything useful about transition, and are increasingly vestigial, a hangover from how oil markets were covered thirty years ago.

To concentrate the mind, therefore, it’s helpful to accept we are no longer in a period of uncertainty about whether transitioning is happening. Technology, the learning rate, and manufacturing ensure its continuation. Rather, we are in a period of uncertainty about achieving actual emissions declines, which cannot happen until fossil fuel consumption steps decisively off the plateau. We might describe this as the battle between path dependency and price: the latter is effective at eroding and undermining legacy systems, but path dependency is like a gnarly stump, hard to uproot. The global delivery system to provide you with 20 gallons of petrol was established a century ago. The new system, to provide you with 50 kWh of power for your EV is still being born.

Coverage of energy transition during the middle phase should emphasize whole system analysis, always placing growth of clean energy in the context of the background growth rate of overall demand. It’s no longer sufficient, or interesting for that matter, to herald the astounding adoption of solar or to throw around the word exponential, because the problem we are trying to solve is emissions, and all good news must be calibrated to that task. To be blunt, your correspondent has had numerous exchanges over the past few months with producers of happy outlooks that claim emissions declines are coming in global power generation, but none will cite the most important number of all: total demand growth—the thing that makes energy transition so hard.

The Gregor Letter is also firmly of the view that the current energy transition is classical, and just like the previous two transitions in the following way: the new sources of energy will confer a transformative efficiency gain upon the global economy, boosting growth, and throwing off savings. Growth will not lead to Jevons Paradox either, as profits will increasingly channel demand towards cleaner, more efficient energy. Economic coverage needs to be boosted, therefore, as does coverage of the individual companies in the global infrastructure sector.

Somewhat paradoxically, therefore, energy transition is entering a challenging period of a different kind. We have big tools to fight climate change and we are using them. We have global buy-in from governments to reduce emissions. And best of all, consumers all over the world are seeing the real savings that come when switching from fossil fuels, oil in particular, to electricity. And yet, there are big blocks of demand that are recalcitrant: coal in India and China for example, and oil in US transportation.

More bracing is that we see an increasing divergence within voting populations that claim they want to do something about climate change, but when given the chance, are not willing to forego any inconvenience. This is why it’s suboptimal to get information about climate progress from overtly political writers and other screechy voices because that perspective inevitably leads to alot of blind spots. Confirmation bias is rampant in the climate coverage space.

To be sure, The Gregor Letter no doubt leans in favor of global political parties willing to support the transition, and contemporaneously that’s been the left. But parties are made up of voters, and here in the US we suffer astounding roadblocks to progress from nimbyism, and resistance to curbs on vehicles in the large, progressive cities of the east and west coasts. Just on that point, car culture is not just an American phenomenon, nor is the unwillingness to give up some car-freedom among voters who otherwise lean left.

Because one of the central forecasts of The Gregor Letter is that global emissions are not yet about to decline, it’s going to be necessary to critique a fair amount of sloppy work in the marketplace right now saying otherwise. This means applying some pressure to one’s own team. The fossil fuel plateau is going to be quite hard to dislodge, and it’s not helpful to keep dangling the promise of declines, or relying on argumentum ad infinitum that exponential renewable growth will get us there. Let’s begin.

Cast a cold eye on life, on death. Horseman pass by! - W.B. Yeats

Natural gas in US power generation continues to grow by leaps and bounds, contrary to the long-term assurances made by some advocates of wind and solar. And there’s a simple reason for it: every time we successfully retire a coal plant, the next unit of marginal growth in capacity is not supplied entirely by wind, solar and storage but must be shared with new natural gas. The path dependency you want: new wind and solar. The path dependency you don’t want: a new natural gas plant. The US has added so much new natural gas capacity since 2010, that generation from natural gas has nearly doubled from 987 TWh in 2010, to an estimated 1815 TWh this year (based on the first 9 months of data). In the chart below, which runs to the end of 2022, note the wonderful growth of wind and solar, but that it’s shared with natural gas.

The Gregor Letter has been sounding the alarm on natural gas growth since the beginning of the year. US natgas in power generation is expected to grow by 7.3% this year, after growing by 7.7% last year. That is extremely strong fossil fuel growth at a time when the US, now led by states like Texas, is very busy building new wind, solar and storage. And this comes after a very good decade in which wind and solar growth in the US has been excellent.

Part of the alarm is that energy transition itself will be judged by its success in moving global energy demand over to the powergrid, thus making it even harder to “catch” total demand growth, and overcome it, exclusively from clean sources. As if on cue, it’s now reported that the era of flat US power demand is about to come to an end, with a forecast from Grid Strategies that the US will start tacking on about 1% of new demand each year over the next five years. Frankly, that will probably be an underestimate, as the US moves tranches of heating, transportation, and other processes over to electricity.

The Gregor Letter is delighted to have a readership that spans the entire world. From the Americas to Europe, from India and Africa to Australasia, here’s wishing you a very Merry Christmas.

The EV only strategy to decarbonize US transportation emissions was always flawed, and now it’s been shown to be risky. US automakers are pulling back on their EV investment and production plans in a broad, sectoral admission that the Big 3 are not ready for prime time. US sales of EV are doing fine, by the way, and the business press seems to have conflated Detroit’s fumble as a proxy for EV growth more generally. Well, according to the latest data, US plug-in sales are on course to rise 50% this year, to 1.375 million units, or a 9% share of total vehicle sales. Given that the US is a laggard, that’s pretty good. And, to the extent the US market can be supplied by Tesla, Kia, and Hyundai among others, there’s no reason to think the EV story is coming to a halt in America.

But there is one concerning data point emerging now, in 2023 US vehicle sales: for the first time since 2016, sales of ICE vehicles are set to grow! ICE sales have fallen every year since the high was set last decade, at 17.3 million units. This year, ICE sales are on pace to rise 8.5% from 12.8 million to 13.9 million. (To be sure, a portion of those will be hybrids without a plug, but they must really be considered to be ICE cars with a helper electric motor). Let’s make this plain: the transportation sector is now the problem child of US emissions, and the country has no effective plan to do much about it. If you are wondering why it’s so hard to get global emissions off a plateau, this is one reason why.

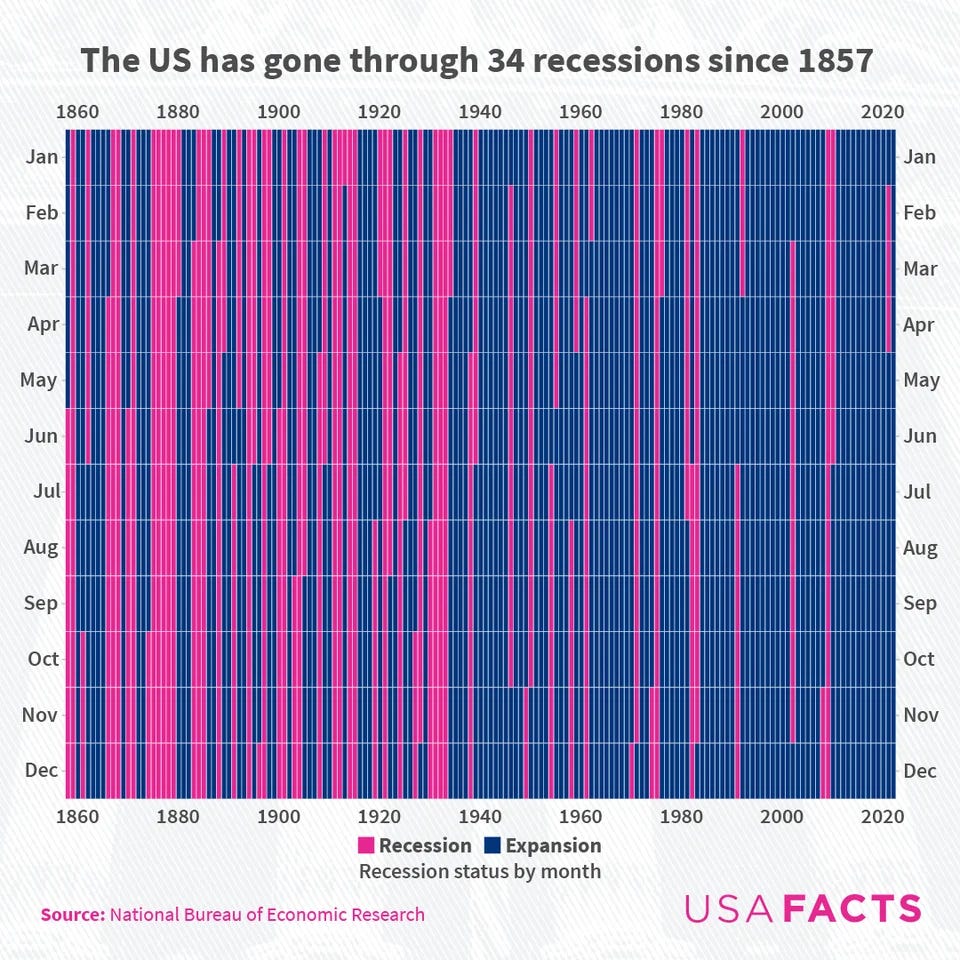

Modern economies develop stabilization tools which lead, over the long term, to increased stability. This chart from USA Facts is graphically helpful and tells a story of a long decline in economic volatility. The advancements in technology, availability of energy, and world trade certainly also have played a role in this outcome. The current energy transition will have a similar effect, dampening volatility from energy commodities as the world moves to manufactured energy that’s embedded in infrastructure. Again, the world needs to take more seriously that the current transition will, like the first two, lead to an economic boom.

Electronic equipment and component manufacturers are recovering nicely in the market, along with other associated industrial names. The First Trust GRID ETF has risen 20% off its Autumn low, as beaten down names like Enphase and SolarEdge recover, along with continued strength in GE, Quanta Services, and Eaton, among others. Lower interest rates are the elixir for this sector, and based on next year’s rate cut expectations from the Federal Reserve, more support is on the way.

New Englanders are highly educated, consistently vote for the Democratic Party, and are concerned about climate change. But when it comes time to do something about climate change, they balk. The metro Boston public transit system is in poor condition. Opposition to offshore wind lasted for a decade, before finally capitulating. New Englanders have been successful in blocking better transmission infrastructure to bring Canadian hydropower to the region (the Federal Government is trying, once again) and no new natural gas supply lines have been built either. Result? The crazy legacy of oil-based heating presses onward, in everything from schools, firehouses, town halls and other municipal and residential buildings. Here is an inset of the national heating map from Maps dot com.

As a (former) New Englander myself, I can tell you that the home heating oil business is still very much alive in the northeast. Typically, you strike a contract in late summer with your provider who offers to lock you in at a rather elevated price per gallon that hedges their risk, or, you can choose to go “naked” and take whatever price is available when winter arrives. Even for an oil forecaster, going naked can be risky. When the cold does arrive, a shiny truck (often replete with old school graphics from the 1940’s) shows up at your house with a hose, and pumps oil into a giant basement tank. It’s totally nuts, and it’s totally real.

—Gregor Macdonald