Concentration Risk

Monday 24 November 2025

In its latest World Energy Outlook the IEA reopened the door to continued growth of global oil demand. This is a change from their outlook of the past few years, to be sure, where they, like others, forecast little to no demand growth after 2025. In the opinion of Cold Eye Earth, however, we shouldn’t be too alarmed by the IEA’s shift in posture. After all, it’s just one of their scenarios (current policy scenario, or CPS), and in this latest CPS, oil demand continues rising—by an aggregate 13% in the 26 years from 2024 to 2050. Looked at more closely, that’s a scant 0.5% of growth per year until midcentury. And it’s probably not a coincidence that this tracks with the sub-1% growth that oil is experiencing lately.

Readers will recall it was British Petroleum that first made the big call on “scant to nil” post-2025 demand growth, way back in 2019. And since that time, a number of analysts have gathered around this year as a pivot point. Why is the IEA suddenly so alarmed? It’s not clear. But here is one possibility: The effort to stop oil demand growth requires intense effort, and in recent years China has led that effort valiantly, followed by a solid and ongoing effort in Europe. But North American EV adoption just isn’t that great, and the current administration is of course doing everything possible to return oil to a stronger position not just here in the U.S. but in this entire hemisphere . If we examine a related IEA chart, "Global new car sales by drivetrain,” one can see how although ICE vehicles globally peaked years ago, around 2017, the rate at which we stop buying ICE altogether and increase purchases of EV still matters.

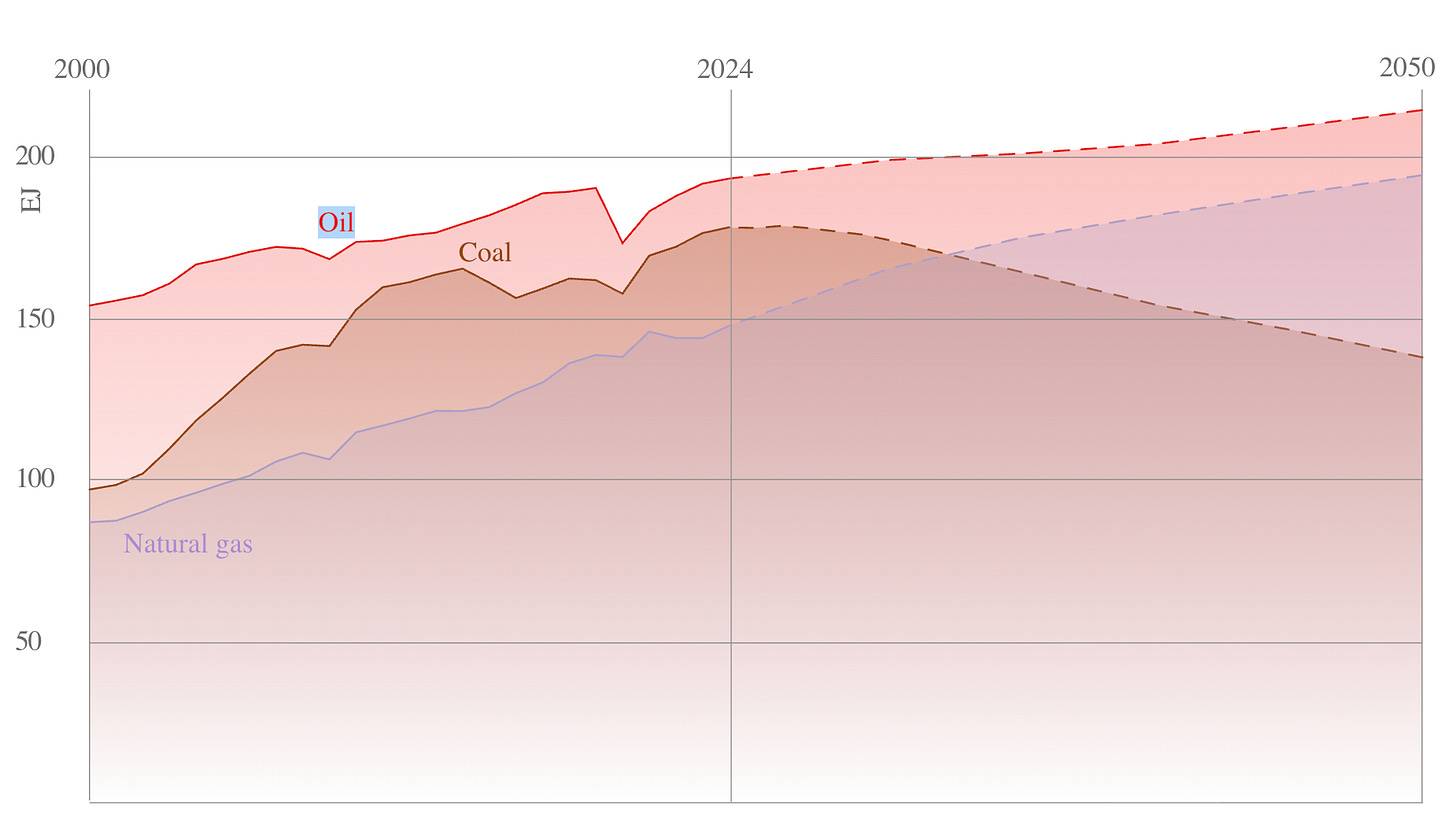

Here, meanwhile, is the fossil fuel chart from the IEA, “Oil and gas demand do not peak,”revealing their shift in the CPS.

You will also note that the IEA sees no peak for natural gas, either. That particular aspect of their forecast looks more solid. Gas has two things going for it. (1) As a partner to variable renewable sources, gas greatly helps the balancing-needs of global power grids—and that will be true even as battery energy storage systems (BESS) continue to grow. (2) In its competitor role, gas has sustained a strong, ongoing capability against coal, and much of the global natural gas fleet is young.

Indeed, the favorable growth prospects for natural gas offer additional help in understanding why growth prospects for oil are so poor: In global transportation, there remains oil dependency but not oil growth. And outside of transportation, whether it be chemicals or an array of industrial applications, there’s simply not enough organic growth to offset oil’s poor prospects.

While we want to be cautious about using the signal from oil prices to strengthen the argument against (much, if any) oil growth in the future, it has become difficult to ignore that the global oil complex has been building inventories, growing spare capacity, and suffering the low prices that inevitably follow those emerging conditions. For at least a year or two now, it’s also been possible to declare that oil prices, on an inflation-adjusted, basis are dirt cheap. Oil was at one time considered an inflation hedge, and for short periods oil may still retain some dwindling qualities under those circumstances. But it’s pretty shocking to see oil at $60 a barrel in the year 2025. That’s after 20% aggregate inflation since 2019-2020 or so, and doesn’t even include the inflation from the previous 20 years. Oil prices first reached $60 a barrel in 2005!—which shocked people and rightly so. But $60 oil in 2025 is little more than a pale, thin shadow of those go-go years.

To be blunt: Today’s oil prices do in fact indicate that demand absolutely sucks, and the futures market (which is not infallible) doesn’t see that changing. It’s also fair to say that the IEA often makes new shifts and declarations right around the time the trends they are seeing reach their apex. To be sure, the Crazy Ivan move in the U.S. toward fossil fuels has been jarring, and the importance of the U.S. in these equations no doubt adds to the overall dark vibes about energy transition in general.

Presently, according to the IEA, global oil demand is on course to advance 0.7% in 2025 and by a similar percentage next year. But overall, oil demand has grown only 3.2% in the aggregate in the five-year period from 2019 through 2024. From a climate perspective, the central problem that oil presents, therefore, is not that it’s going to keep advancing, but rather that it’s just not on course to decline.

The IEA has of course updated their other main scenario, the Stated Policies Scenario, or STEPS, and that has led them to muse and speculate over various peaks. Cold Eye Earth likes this scenario much better, and overall it seems more in tune with current trends. (Indeed, the CPS increasingly looks like a rearguard move by the IEA that gives them credibility in case “all this energy transition stuff” doesn’t work out very well.) For example, in the STEPS, oil demand stops growing around 2030; natural gas reaches its maximum level ten years from now, around 2035; nuclear generation finally grows again on a sustainable basis; and coal keeps going for a while but really starts to fall off hard by 2030. You can see all those projections in the chart below, also from the IEA’s 2025 Outlook.

It’s no surprise that nuclear fares so well in the STEPS. Nuclear is the perfect example of a technology that truly lives and dies on the back of policy changes. And yes, that remains true even if you posit that the new wave of SMRs comes to fruition. Everyone is aware that many countries around the world are coalescing to promote a nuclear revival, but to achieve the IEA outcome shown here will require countries to actually follow through on their plans.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cold Eye Earth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.