Demography of Cars

Monday 27 June 2022

There is considerable uncertainty over the lifespan of the global ICE fleet, which matters a great deal to the trajectory of decarbonization. We are all enthusiastic about the roaring adoption rate of electric vehicles, and electrified transport more generally. The transition to the battery drivetrain in cars, buses, trucks, and smaller devices like two and three-wheelers is a sight to behold. Indeed, electrics are spreading so quickly now that the total annual volume of oil they displace is no longer scant, but meaningful. In previous letters this year, this publication has offered the rough estimate that at current vehicle adoption rates, somewhere between 0.45 and .50 million barrels per day (mbpd) are being avoided. As global EV sales then rise above the current 10 million rate, that displacement will only grow.

More broadly, however, we learn from Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) that in 2021, the total global fleet of all electrics displaced an estimated 1.5 million mbpd of oil. That’s big. Really big. In fact, in a global oil market that’s roughly been running between 95-100 mbpd per year for a while, the typical annual change is right around that 1.00%-2.00% level. If BNEF is right (and they probably are) total global electrics have now grown large enough as a fleet to entirely counter annual oil demand growth.

But looming behind the happy story of EV adoption is the stubborn power of the existing ICE fleet. And analyzing how much further that fleet will grow is a challenging prospect, given the variables. First, quite obviously, the world continues to see annual ICE sales, despite the fact that global ICE sales peaked over five years ago in 2017. Second, owner dispensation of their older ICE cars turns on whether those vehicles are sold for scrap, or passed onward into the used car market. Finally, there is the average lifespan of ICE vehicles which in the past decade has been lengthening.

Just one anecdotal observation: it is truly amazing how many Toyota Camrys and other Toyota models from the pre 2010 vintage still populate the roads. And a further observation: notice how similar to population demographics is the project to chart the future course of the ICE fleet. Cars, like people, experience births, deaths, and some measure of longevity. Combining all these factors into a forecast is challenging.

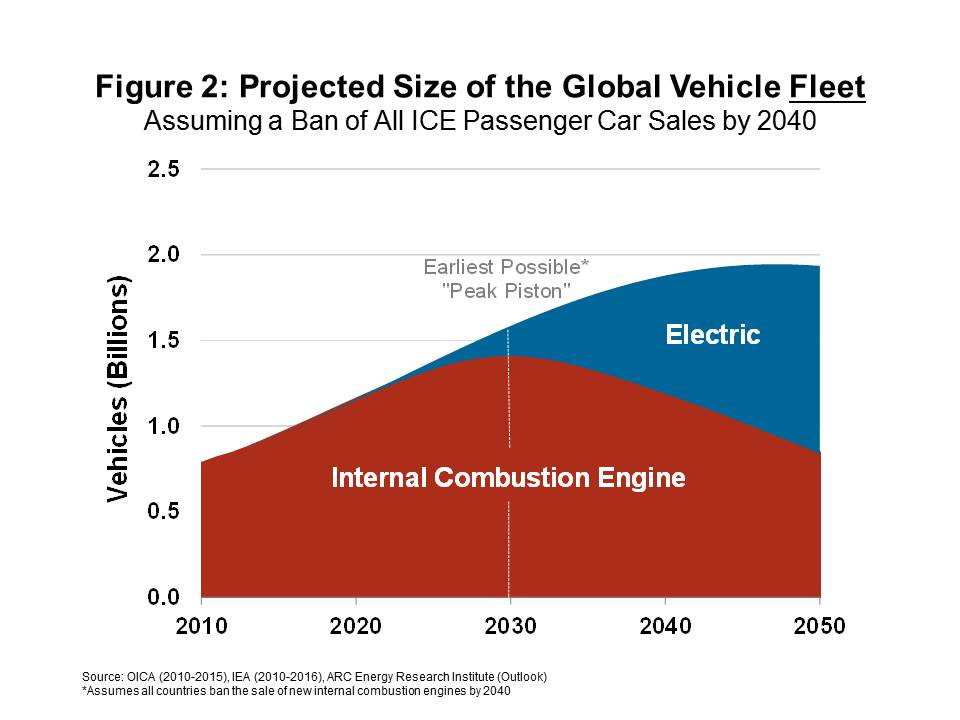

So, let’s take a look at a few forecasts that project how the existing ICE fleet will evolve, in the years to come. The first comes from the Arc Energy Institute of Canada, whose director is Peter Tertzakian, the well known energy analyst. Although the projection here was published in late 2017, it’s worth considering that few understood at the time that global ICE sales were in the process of peaking. It should be further pointed out that a flurry of academic work was emerging right around the 2015-2020 period showing that the lifespan of ICE cars was lengthening, quite substantially. Given those top down views, the Arc Energy chart projected that the size of the global ICE fleet would peak in 2030. Not a bad call, frankly. And remember, a number of very important developments—from the big upswing in China EV sales starting in 2018, to the pandemic’s suppression of ICE sales in favor of EV sales—were yet to come.

Far more recently, however, BNEF has also made a call on the peak ICE fleet. What year peak? This year, 2022, apparently. Notice again how the chart below is exactly like global population projections that are adjusted every few years based on births, deaths, fertility rates, and longevity.

What are some of the developments that account for the acceleration into a global peak for the ICE fleet? Well, five years ago, many analysts were convinced that harsh policies, like future ICE bans, were the main driver in fleet evolution. Now we see that it’s technology, and consumer preference driving the change. There was also concern five years ago that legacy automakers were not moving fast enough to switch platforms; but strategy since that time has pivoted swiftly at Ford, Hyundai, and Volkswagen. The pandemic also put in a twist in the automobile cycle, depressing temporarily what would have been a continuation of normal ICE sales.

There is also a risk that ICE fleet demographers get blindsided by another dynamic called the Osborne Effect. The last issue of the letter explained this phenomenon in plain terms:

One possible explanation: with the knowledge that EV are the future, and that petrol prices are volatile and punishing, buyers may be keeping their ICE vehicles as long as possible, having already made the decision that their next vehicle will be electric. The very idea that one would go out today and purchase a new ICE car, thus locking in dependency on oil for the next 7-12 years, is both comical and absurd.

In other words, the Osborne Effect has probably been in play now for several years, especially in the US which is the one major global market that has remained far behind the EU and China in EV adoption. Holding on to ICE cars in the US may have created a kind of shadow bulge in the US ICE fleet that could lurch downward, as consumers finally pull the trigger on a new EV purchase. Yes, this would flush alot of ICE vehicles back out onto the market, many even sent to the developing world—a point the aforementioned Peter Tertzakian makes in a recent Odd Lots podcast. But it’s also possible that a good portion of these older cars don’t have much resale value, and are near their terminal age, bound for scrappage.

Finally, there is one more effect that should be considered here. At the front end of the BNEF report on EV was a fascinating chart showing that, right now, the bulk of annual oil displacement is largely coming from the faster turnover in the two and three wheeler market to battery power.

That’s powerful in two ways. First, it’s just plain impressive that this sub-market is moving so quickly, because it forecasts overall potential for speed in transition. But mainly, it underscores the fact that the big wheel about to turn in oil displacement really does come from EV. As the US starts to join China and the EU in adoption—especially given the far lower efficiency of US ICE cars—the impacts to come could be rapid.

Final note: global EV sales are expected to rise to a 13% market share this year.

The IMF has slashed the US growth outlook, after a round of global macro data turned decidedly weaker. US growth was slashed from 3.7% to 2.9% as the IMF forecasted the US would avoid, but only narrowly avoid, a recession.

Both EIA and IEA meanwhile are stubbornly clinging to their most recent estimates of 2022 oil demand. Given macro volatility, and increasing levels of uncertainty, The Gregor Letter is not making a precise forecast for demand this year, but remains confident both EIA and IEA soon will be again slashing downward, from their current call +1.8 mbpd of growth. You can’t cut US economic growth nearly a full percentage point and wind up the year with over 2% global oil demand growth. Outside of a miracle, like the assassination of Putin and a hasty withdrawal from Ukraine, combined with a Fed that starts to slow its tightening campaign, global oil demand will eke out at best an advance of +1.2 mbpd of growth, simply because China is getting back to work.

Data note: the reason previous years adjust slightly from month to month is that the agencies are always revising their estimates of past demand. In fact, sometimes both agencies revise an entire decade of demand. It’s never by large amounts, but it bears mentioning. With the latest IEA estimates just released, the current baseline year of 2019 is now pegged at 100.44 mbpd. Final note: The Gregor Letter pays attention to EIA estimates of global oil demand, but largely prefers to chart the IEA data as that agency is far better at global estimates.

Notice that 2022 demand remains weak, even in the current forecast of EIA and IEA. 2022 global oil demand remains on track to come in at least 1.00% below the baseline year of 2019. Human thinking of course can get very persuaded by price, and therefore high prices bathe society in the assumption that demand is strong. But it’s not. And given that more cuts are coming to global growth, we are going to learn all over again that high prices are the final cure for high prices, as the demand response finally kicks in.

Expectations about inflation and interest rates are changing once again, as the last man standing—the global commodity sector—tumbles in price. We are now getting a far clearer picture of global inflation, and its contours. Simply put, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the trailing strength in the global economy placed price pressure on everything from wheat to copper, and of course natural gas and oil. The ever rising price level in natural resources was stirred into the increase in wages, supply-chain constraints, and the effects of extraordinary monetary and fiscal support. Only 1-2 months ago, therefore, inflation seemed to be coming at us from all sides.

But it’s not. As Fed chairman Powell made clear, one piece of the inflation puzzle is not driving readings higher and that’s wages. There is no wage-price spiral, at least not here in the United States. Paul Krugman meanwhile has updated his latest view and come to the conclusion which others are now embracing: if wages are not the primary problem, and everything from house prices, to business investment, to used cars and goods is starting to recede from the highs, what’s left? Energy. Metals. And soft commodities.

Let’s turn to the behavior of the 10 Year Treasury yield, which has once again been “rejected” at levels above 3.2%. When the bond market added up all the weakening macro data, and then saw prices in everything from cotton to copper falling in price, it reversed once again it’s probing above that key level, and headed south again, finishing the week at 3.13%.

Perhaps it would be most helpful to describe the thinking now coming into the bond market. From reading a number of thoughts from long-experienced market observers, here is a kind of composite of the current view:

The Fed got started late on actual rate hikes. But the bond market actually got things started for them, way back in Q4 2021 as the 2 Year Treasury Yield began its dramatic ascent. So while the Fed funds rate currently is “only” at 1.5%, the effective rate applied to the economy through the 2 Year has been skimming along at a much higher level, around and even above 3%. That’s why you have a sharp slowdown in housing, for example, where mortgage rates have soared. Presently, however, the Fed is capitulating to trailing data, like Headline CPI, when in fact the growth outlook is starting to turn sour. And with it the inflation outlook—also turning lower. When the bond market saw the Fed “react” on a Wednesday to CPI data that had just been released the previous Friday, the conclusion that settled in quickly was that the Fed was now behind the curve of a growth slowdown, in the same way it’s been behind the curve of inflation. Global PMI readings were not good. US flash PMI was not good either. But if the Federal Reserve is going to hike rates regardless of incoming data, only focusing on the latest Headline CPI or PCE, then the bond market can do that math pretty quickly and come to the following conclusion—it’s time to buy US treasury bonds again in anticipation of a very effectively created slowdown, and decline in inflation.

The US treasury bond market can be a difficult one for many people to understand. A simple and effective way to think about it however is that it’s simply a barometric pressure reading of future growth, and thus the potential for firmer inflation. It really is that simple. Are the Fed and the US government undertaking policies that will meaningfully raise future GDP growth? Well then, you should probably own fewer US treasury bonds, or if you do, own US treasuries that are shorter in maturity. Don’t own 30 Year bonds. Own 3-7 Year bonds. But what if the Fed or the government are undertaking policies that will reduce future growth? Then you should consider owning more US treasury bonds, longer ones especially, like the 10 Year and the 30 Year. What’s probably confusing right now to casual observers is that we may have just pivoted from a regime of inflation and growth-driven hikes in interest rates, to a regime of receding inflation and growth-driven cuts in interest rates. Here, the word “cut” includes not just interest rate declines in the bond market, but anticipation of future Fed rate cuts. Or even just a pause in Fed rate hikes. Indeed, expectations for Fed rate hikes in the 2H of 2022 are being lowered again. Whereas markets thought the Fed funds rate could easily get above 3.5% or more , now the market is no longer as confident that we even get much beyond 3.00%.

This is how markets behave during a transition phase, when visibility—even in the near term—is hard to acquire. One week the US 10 Year is freaking out about a CPI release and pushing higher in yield. Only a week or two later, the US 10 Year is going decidedly in the opposite direction, signaling that CPI has now surely peaked. The signs are mounting: if your thesis is that inflation gets worse from here, or stays elevated from here, you have fewer and fewer price points to support your forecast.

US road fuel consumption also remains weak, above levels of 2021 but still not back to the baseline year of 2019. Voices claiming that no demand destruction was taking place at the pump have now fallen silent. Pro-tip: avoid getting sucked into single week data points on US gasoline consumption, a specious and valueless piece of information that the media uses to produce headlines, often about travel over three-day holidays. In addition to the fact that single week data is nothing but pure noise, you will rarely if ever be offered a useful baseline on which to judge it.

Here is US gasoline consumption, with an annualized 2022 estimate based on the first four months of data:

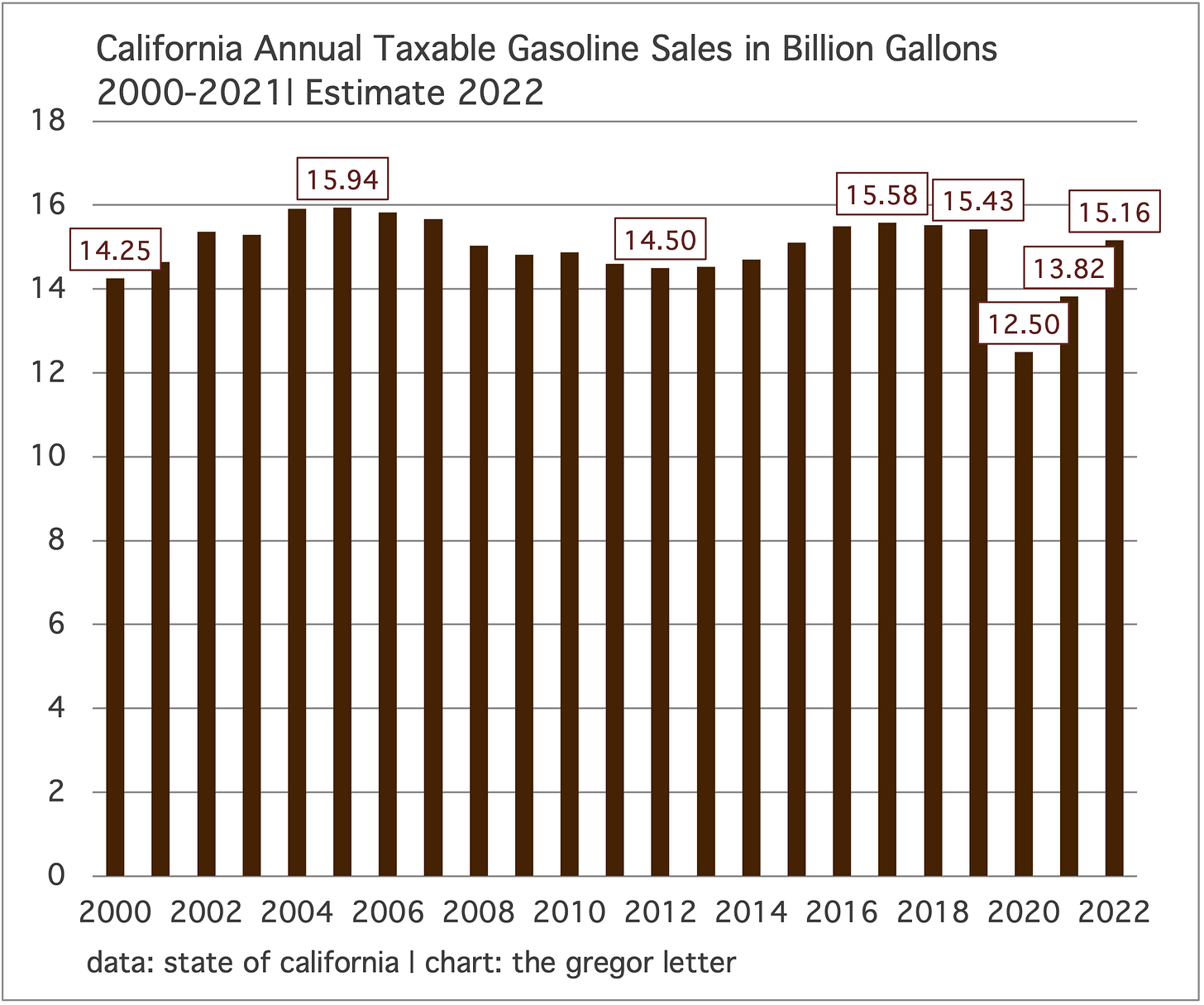

And here is California gasoline consumption, annualized for 2022 based on the first three months of this year’s data.

Both of these 2022 estimates of course don’t include the most recent months, where we are getting confirmation that US petrol demand has weakened further. With California demand about 1.7% below the 2019 baseline, and US national demand about 1.9% below the baseline, the revelation about weak US demand will show up even more clearly when we learn that, yes, Americans did get out in their cars this summer—just not to the extent that fulfilled the forecasts of a big reopening of the economy.

There are indications Washington sees the threat to global oil supply should EU sanctions land as intended, later this year. There is no secret about the fact that Russian oil continues to get to market. The New York Times had a lengthy piece on the subject late last week. While the NYT largely misunderstands the implications, thinking that greater proceeds from oil sales is a sign of failure, the story will help readers understand commodity economics. Operationally, higher capital flows into Russia from oil sales, at high oil prices—which ironically are the result of the energy sanctions themselves—are not important because broader trade both in and out of the country is greatly curtailed. In other words, Russia’s lower trade deficit is the result of its inability to make purchases.

Apparently, however, advisors to the Biden administration now see the threat of the EU pressing the insurance lever, which would very effectively start to curtail Russian oil from the global market. It is frankly astonishing that both Brussels and Washington did not adhere to the original sanction scheme, which was excellent, and instead kept going to attack energy supply. How could policy makers have deluded themselves into thinking this was a good idea, or that western economies could handle the impact? The Gregor Letter covered the EU’s sixth sanction package and its focus on the insurance factor just in the last issue. Perhaps policy makers are finally listening.

Just to review: the original sanctions were absolutely necessary to counter Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Arms shipments to Ukraine have also been necessary, and the right thing to do. Frankly, a more direct military confrontation by NATO against Russian forces, exclusively on Ukrainian soil, would be justified. The Gregor Letter has been crystal clear that Russia has revealed genocidal intent, and that merits a response from the West despite the perceived risks, because it is even more dangerous to allow such aggression to carry onward. All actions taken so far by the West have only hurt the West a little, and hurt Russia greatly. Let’s call it 90% of the pain on Russia, and only 10% of the pain on the OECD.

But the energy sanctions themselves turn that 90/10 proposition upside down. We must acknowledge that the West is essentially at war with Russia. And if you have an opportunity in a war to keep oil prices more stable, rather than less stable, you should take it. The energy carve-out in the original sanction package was the correct strategy. It meant we could fight Putin, wreck his economy, disable supply chains that would help his military resupply, apply pressure if not suffering on the Russian people, and damage his industrial base. All the data we have so far show the original sanctions are working, and becoming more devastating over time. As The Gregor Letter goes to press, Russia is about to default on its sovereign debt.

Unfortunately, this strategic error by the West has now inevitably triggered recession risk across the OECD. Europe is almost certainly on the brink of a recession, if it’s not in one already. And the US is close also to recording two quarters of zero growth in the first half of this year, with more risk to come. The strategy against Russia from this point forward should be to place further pressure through the geo-political lever, while abandoning the energy sanctions. Doing so would exploit the oil market against Russia, and not against ourselves.

—Gregor Macdonald