Disruption Disrupted

Monday 27 December 2021

A flotilla of American ships bearing volumes of LNG has headed to Europe. Along with some moderation in continental weather, European natural gas prices fell dramatically going into the Christmas weekend. Of course, given the nosebleed levels reached recently in EU natural gas prices, that’s not saying much. At one point during the most recent peak of the gas shortage, prices crested over $60 per million btu, or in barrel of oil equivalent (boe) terms, over $300. For reference, US natural gas prices have traded between $3.75 and $6.50 per million btu this Autumn. Bloomberg, who has followed the LNG flotilla story, has even provided ship tracking data to better portray the surge. A chart of the Dutch TTF natural gas contract is below, showing the most recent decline. Note that while the gas prices fell over 25%, they remain totally unmoored from their longer term average.

We will spend years debating the sequence of crisis and recovery as regions move through energy transition. Europe’s strong penetration of wind and solar into its power system is being blamed now, for example, in a line of argument that duplicates the one used to explain the Texas winter blackouts of earlier this year. In both cases, serious problems with the existing natural gas system were the primary cause. In the case of Texas, the long term investment failure to winterize NG pipelines crippled the entire system. In Europe, a politically motivated constriction of NG pipeline supply by Russia is, and remains, the primary pressure.

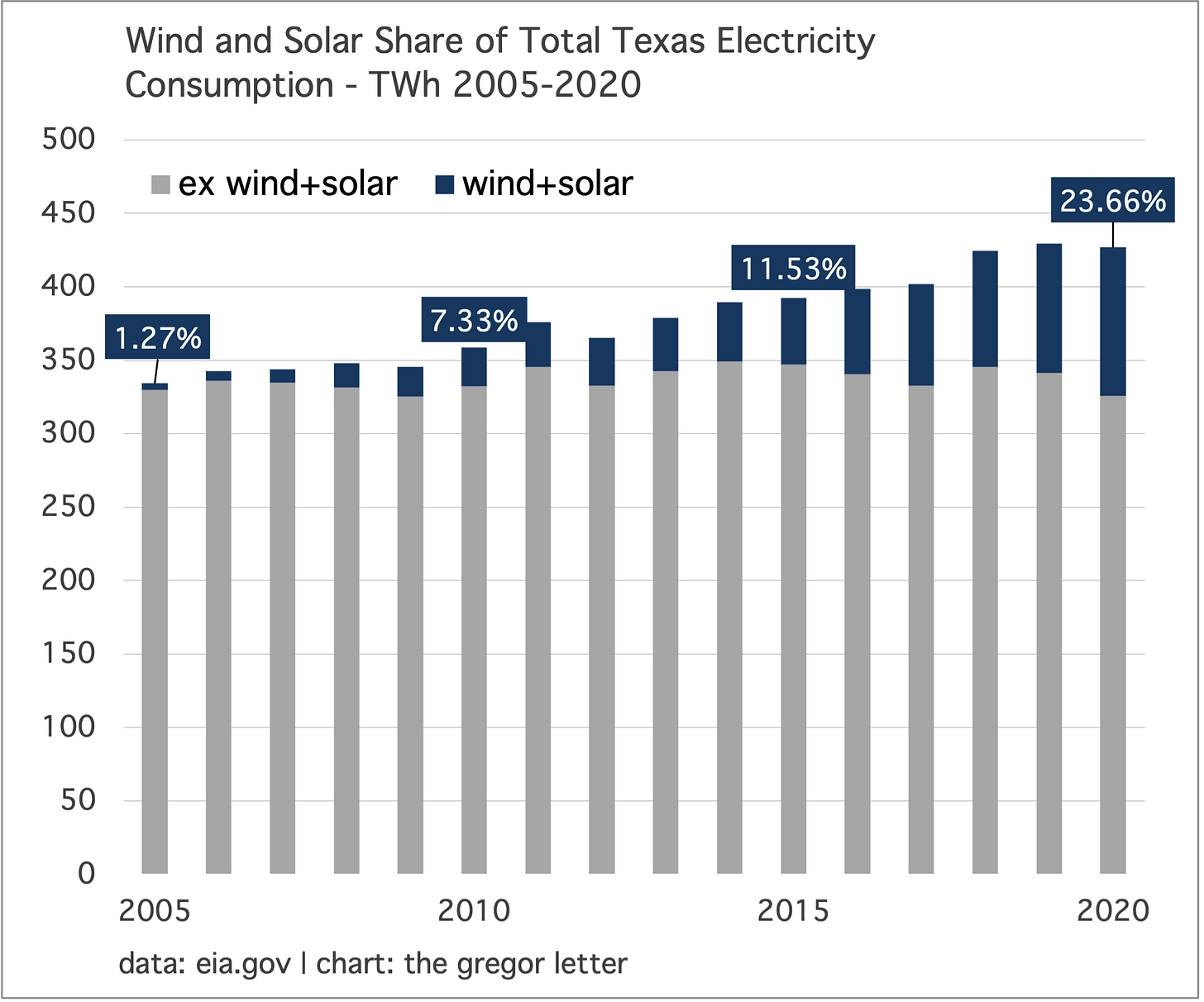

There is no argument that the US and Europe however have shed both coal and nuclear from their grids. And that has incrementally increased dependency on natural gas, making the system more brittle. In addition, both the EU and the US need more storage to “harden” the large volume of wind and solar generation on which both regions are increasingly dependent. But it must be said: there was no magic penetration threshold that wind and solar crossed in either Texas, or Europe, that “caused” the crises. Texas like California is already heading towards a grid that is 25% powered by wind and solar.

And when you look at the chart below, of wind+solar’s share of power in the European Union, we should ask: why didn’t a winter natural gas crisis develop years ago? After all, combined wind and solar was already above a 12% share six years ago. Texas and California have similar trajectories. Again, no crisis until the “special” year of 2021. What was so special? Unusually low temperatures exposing the vulnerability in Texas pipelines; and Russia deliberately squeezing Europe in a power play.

The disruptive nature of energy transition is exciting, but will increasingly draw blowback. One is reminded of the Silicon Valley dictum to start-ups: move fast, and break things. To understand how the accelerating transition to wind, solar, batteries, and EV is throwing a screwball into the global economy, it is better to entirely avoid the error that these new technologies are causing trouble through their own functioning. They function well. They are cheaper than the incumbent technologies, and they create savings by controlling waste. But their advent—the mere knowledge that they are advancing like an army onto the existing system—is creating disruption in the flows of normal investment and maintenance. The disruption is itself being disrupted, therefore, because the world remains dependent and tightly coupled to the incumbent methods. This back and forth process will at times become less liquid, and will propagate push-pull dynamics into the global economy. Let’s look at some of these dynamics that have either already revealed themselves, or will step towards center stage as we head into 2022:

Inflation spikes: Energy transition amplifies the cost and price difference between inefficient fossil fuels systems and new energy technology. Paradoxically, instead of making natural gas or oil cheaper through relaxed demand, however, the risk of lower demand triggers supply chain illiquidity in fossil fuels, causing a grand unsmoothing of the delivery system, creating price spikes. Some of this is behavioral, but much of the phenomenon is increasingly structural: who is going to build more natural gas storage or oil pipelines or coal export capacity at this juncture in economic history? And because fossil fuels form a major component of inflation readings everywhere, these price spikes can mangle forward looking interest rate pathways. This could, in the extreme, blow back to the cost of capital for new energy technology.

Political blowback: For a considerable minority of the global population, blaming renewables for the pressure they place on the existing fossil fuel system is a very convenient route to pressure politicians to enact rescue measures for coal, oil, and natural gas. The antecedents to such a phase have been building for years. The US State of Ohio actually produced a major corruption scandal in this regard, in a doomed attempt to rescue legacy generation, suppress renewables growth, while also lining the pockets of elected officials. More broadly, one could even regard the election of Trump in 2016, and his campaign, as one that successfully leveraged the long and steady decline of coal-related jobs in the tri-state area of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. (Not to mention the political malpractice of the Democrats and candidate Hillary Clinton, in particular, to both address and treat that set of conditions with basic care.) Indeed, one could make a decent case that not only was energy transition already taking place years ago, but the failure to handle it properly shifted the political trajectory of the United States. And those pressures are still very much alive today, as they spread from coal to natural gas and oil systems. If you take seriously what long-term economic decline in the coal system can produce politically, imagine what happens when refineries, oil field jobs, and a whole constellation of other FF related industries go into decline.

Pedal to the metal: Price spikes in petrol; utility bill spikes from soaring natural gas; logistics problems with the delivery of coal and natural gas; and continued cost inflation in running the inefficient fossil fuel system—all these will drive consumers and owners of capital to run even faster towards EV, batteries, wind, and solar. It’s a certainty now that the price recovery seen this year in oil will be found to have uncovered a new tranche of EV buyers, especially in domains like China and Europe where model variety and consumer choice is abundant. And even in domains where the blame game is running strong, like Texas, the mounting of new rounds of wind and solar deployment is pressing onward. The pedal-to-the-metal dynamic is a companion to the supply-chain price spike dynamic, in that it feeds off fossil fuel problems, and responds to them with even faster adoption. This is the sunny side of transition. The faster it moves, the faster it moves.

Bottlenecks in materials availability: There simply isn’t enough lithium or battery manufacturing capacity to fulfill expected EV demand next year, let alone accelerating demand. Tesla, on this measure, remains far better positioned than the rest of the automaker complex, it should be pointed out. To underscore our current position, merger and acquisition activity in the lithium sector has now begun. Rio Tinto, which has been rebuffed in its attempt to start development on a lithium mine in Serbia, has just announced it will purchase for $825 million a project in Argentina. The offer follows previous deals in the 2H of this year, as Ganfeng and CATL have both raced to lock up lithium supply. At the very least, this means that battery prices will either not fall at all next year, or will fall less aggressively, and for short periods of time may even rise.

One dynamic that readers should contemplate: in 100 years of auto manufacturing OEM responsibility in the area of propulsion was limited to the fuel tank, and its supply lines to the engine. Not a particularly demanding part to produce, nor one beset by bottlenecks. If you did not have the material to build a fuel tank, you probably didn’t have the materials to produce the body, either. Now, however, there is a revolutionary pivot underway that places a radically new responsibility on automakers. The production of the battery pack is itself a complex task, with its own unique supply chain. Automakers never before had to contend with either.

Environmental roadblocks: While the buildout of new energy infrastructure and the electrification of transport does not represent a larger call on natural resources—when compared to running the system in its current form—that doesn’t mean that resource extraction will not run into roadblocks. Simple explanation: renewables call on a new set of resources, lithium and cobalt in particular, along with the usual suspects like copper. Rio Tinto was rebuffed in Serbia on environmental grounds, and it’s a lock that here in the US any and all efforts to develop lithium deposits will at least run into regulatory hurdles. This will once again open up a new pathway for environmentally dirty processes to be offshored, outside the OECD, to the developing world. And it’s already underway: cobalt extraction in Africa, polysilicon production in China, and lithium extraction in South America.

Already big, the Lone Star State is going even bigger on wind, solar, and storage. Texas would seem to be a prime domain for a big pushback and then rollback of new energy infrastructure. Popular culture is convinced, despite the facts, that wind power was responsible for the winter blackout disaster earlier this year. Moreover, there is a national migration going on, especially from California, into Texas. And part of the narrative driving that migration is the notion that California—where EV and renewable adoption remains robust—has become a problem. And yet, on top of an already heady market share for combined wind+solar, Texas is about to supersize clean generation and storage in particular. First, let’s take a look at the penetration through 2020 of wind and solar in the Texas system.

Counter to the political blowback thesis offered in today’s letter, the state of Texas is preparing to significantly add solar capacity after heavily favoring wind power growth for the past decade. Perhaps more significantly, the state is really getting very aggressive on storage, and storage buildout plans. That makes so much sense, of course. Texas has engaged some early tactics to make better use of its gargantuan volume of wind power, by creating time-shifting demand incentives for consumers. But storage is frankly the ultimate answer to the problem. According to an analysis of the most recent projections from ERCOT, Texas solar capacity and storage capacity is set to double by the end of next year. But there’s more. Other energy analysts are looking at the ERCOT connection agreement queue—which is not a guarantee, but an indication of the aggregate project pipeline—and are showing that solar and storage in particular continues this stepped up pace for 2023 too.

The Gregor Letter has made the point previously that high penetration domains, like Europe especially, needed to start thinking about shifting deployment to storage not upon achieving higher levels of renewable penetration but rather, when it became clear that wind and solar were exiting the policy-support regime and would grow henceforth quite quickly on their own. That appears to be the recognition now taking place in Texas.

News Briefs: The first full conversion of a UK petrol station into an EV charging station has taken place in Fulham, London. (see photo, above). Shell hired an architect to make a statement and frankly, why not? • Chamath Palihapitiya was named Financial Charlatan of the Year in a not very meaningful, but nevertheless entertaining Twitter poll. It’s a cautionary tale however and one very on topic, because the SPACS that Palihapitiya sponsored with great salesmanship were mostly in the green energy space and have not turned out well, at all. Desktop Metal being a prime example. • Scientists at Walter Reed in the US are expected to announce they have created a single vaccine that will counter all variants throw at us, by the pandemic. It has be noted that the treatment of disease has historically been a major focus in military history, and this time appears to be no different. • The combination of a shift in posture from the Federal Reserve, slowdowns created by the omicron variant, and the amount of consumption already pulled forward could actually create a big slowdown in the economy in the first quarter of this coming year. If you are wondering how could inflation have already peaked, well, that’s how.

Economic forecasts for 2022 are widely dispersed, as energy prices, inflation, and monetary policy are quite unknowable. The usual suspects (all the financial institutions) are of course in the process of releasing their 2022 outlooks. The Gregor Letter takes a far more singular view of next year: if inflation has already peaked, the global economy will experience fewer disruptions, equity markets will be strong, global deployment of renewables will be super strong, and populations will begin to accept more broadly that clean power and electrification of transport is inevitable. If inflation however does not abate, then central banks will have to be more aggressive in their various forms of tightening. That will put most of the favorable trends not into reverse, exactly, but into a time-out period that will itself cause problems.

One counterintuitive dynamic that may show up again, however, is that interest rates could actually wind up falling if inflationary pressure is sustained because interest rates may respond more to the reaction of monetary policy, rather than inflation itself. Should that dynamic unfold—and you could argue we’ve had a small preview already, with interest rates coming down from their peak in the wake of Federal Reserve communications about tapering and tightening—then a middle path could be struck as global renewables would continue to thrive under a low rate regime. It must be pointed out, for example, that the rest of the world is not going to tarry and delay simply because OECD monetary policy has entered a tightening cycle.

But if interest rates did become more legitimately concerned about inflation, and actually expressed enough concern to doubt the ability of monetary policy to get inflation under control, then global economies could indeed be in for a rougher ride next year.

The Gregor Letter base case for this decade is also pretty straightforward. Global oil and coal consumption have now peaked. Every layer of the global economy that transitions to clean energy will run at both a lower cost, and at a cost that is superior for long-term planning. Trillions will be invested in this transition, providing steady employment demand for the world’s workers. And, the transition will spread throughout the world, not just to developed but to developing economies. Best of all, this grand adoption of new energy technology is intrinsically deflationary, clawing back the enormous waste (and costs) associated with fossil fuel combustion.

If you are an investor (and The Gregor Letter enjoys broad readership among professional investors) the longer term decade view is your guiding light. To make this clear: energy transition will create significant capital surpluses as inefficiencies are removed from the system, and those surpluses will function not unlike a peace dividend—of the kind we saw when the Berlin wall fell, continental credit markets converged, and a great deal of long pent-up demand was released into the global economy. The analogy is helpful also, because it illustrates the flowering that can occur when moribund methods and approaches are abandoned. Indeed, “high prices” more often than not are a reliable outcome of dysfunctional processes and the Soviet Union for many decades acted as a kind of giant, squatting on the productive potential of hundreds of millions of people. Like fossil fuels, the Soviet Union was indeed powerful, but was no match for better methods.

The challenge as always is the near term. Note for example how incredibly clumsy and inept the United States is with regard to its own approach to energy transition. A far smaller amount of capital than is ever budgeted by the US could be deployed to soften political opposition to transition by going directly to the population centers which will be hurt most by the downfall of fossil fuels. But no. Instead, the US wastes time haggling over tax incentives and does not seem to be able to grok a simple point: many of social goals hotly pursued by progressives could also be achieved through wisely targeted infrastructure programs—that is, programs which could be distributed fairly among 50 US states. But instead of being a central idea, plans such as these languish at the margins.

2022 probably doesn’t stand, however, as a pivotal year for these questions. The world is still trying to wrestle free of a pandemic that has run for nearly two years now. If the omicron variant does in fact turn out to be the way the pandemic ends—boosting vaccine participation while at the same time converting the initial coronavirus into something more endemic and survivable—then the story of 2022 will be far more dominated by that outcome than inflation or energy transition. As usual, therefore, visibility over the near term is clouded by volatility in the near term. If the first half of 2022 is indeed more volatile, then one way for investors and policy makers to exploit such a landscape will be to seize upon any glaring (and temporary) mispricings that may arise, and which are out of alignment with the expected pathway forward to the end of the decade.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.