Downed Wires

Monday 26 May 2025

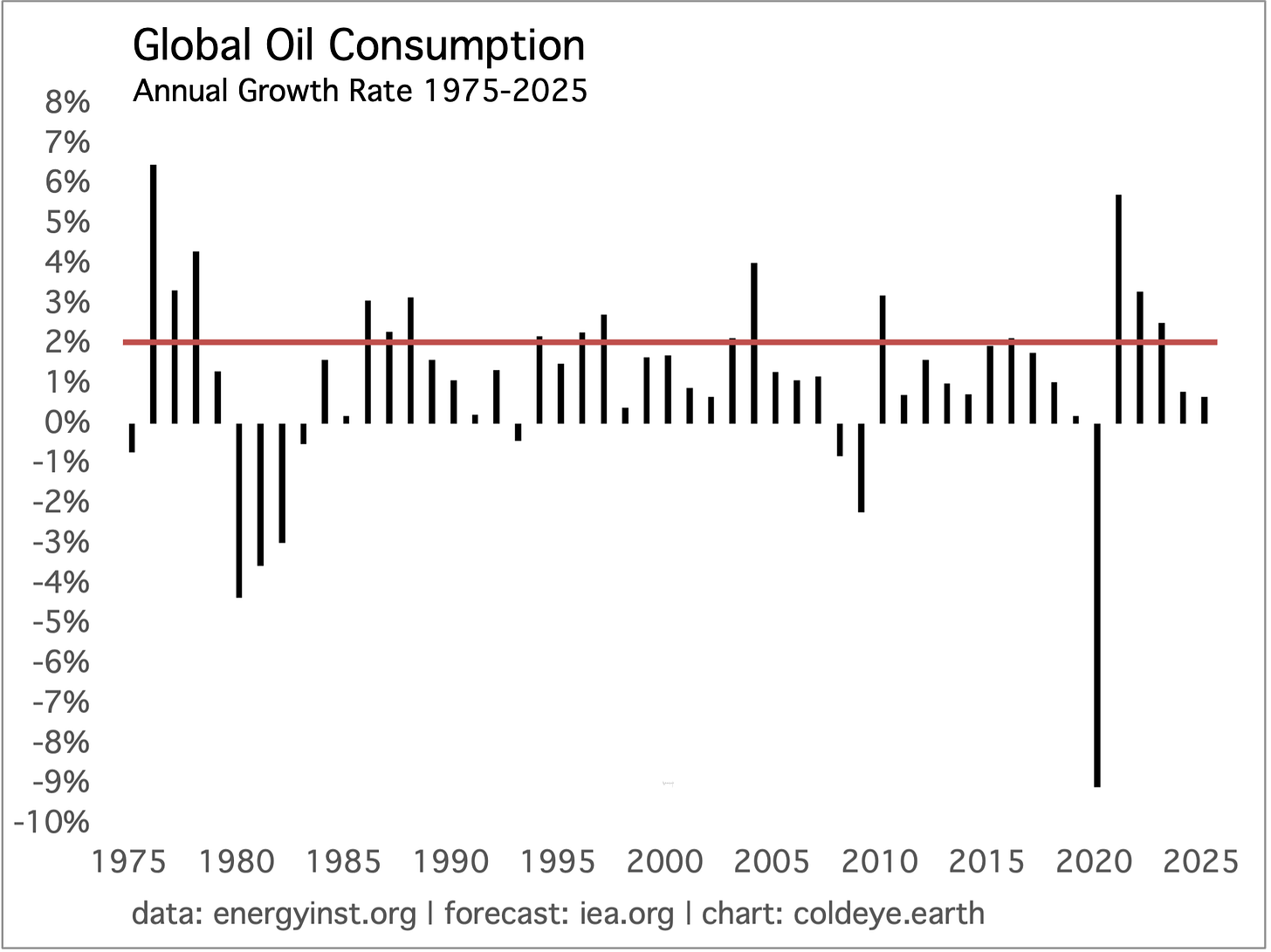

Global adoption of electric vehicles continues to place a steady drag on the growth of oil demand. While this displacement process is slow, due to the constant lengthening of the fleet turnover cycle, total on-road fleet of global EV avoided roughly 1.3 mbpd (million barrels per day) of consumption in 2024, according to a new report from the IEA. Now, 1.3 mbpd of annual consumption savings is small in absolute terms—just a bit more than 1% in a market that consumes around 102 mbpd. But compared to marginal growth, which in recent years has run at a slower annual pace, the savings are quite significant. EV adoption is taking place in an era when annual oil demand growth is already weaker, compared to much of the 20th century. And now, EV adoption itself is adding to the downward pressure. For a long while, it was typical for annual oil demand growth to either reach or exceed 2%. In recent times however, oil demand has either struggled to exceed 2% growth or more often has fallen back to 1.0 - 1.5%.

While global oil demand is now currently around 102 mbpd, the oil market’s price setting mechanism is driven by the 1 -2 mbpd of oscillation of demand that occurs from year to year. Push annual demand growth to 2.00% of more, and prices will strengthen notably. Relax demand growth to 1.00% or below, and market pricing will also relax. After rebounding from the pandemic lows, global oil demand rose only 0.78% last year, and is expected to only grow by 0.67% this year, according to the IEA. That’s just not enough to support oil prices and explains the current weakness, as oil trades in the low 60’s. Just to remind: those are dirt cheap prices on an inflation adjusted basis.

The IEA’s report forecasts that by the year 2030, EV adoption will be displacing 5 mbpd. Progress to be sure, but not exactly revolutionary. The current trajectory of EV adoption, combined with the enormous path dependency of oil, is probably enough to bring demand growth to a sustainable flatline (if we are not there already). But the economics of EV adoption are not aggressive enough to remove economically viable ICE vehicles from the working fleet. EV don’t render existing ICE so worthless that they can be tossed away. This is now a familiar theme to readers of Cold Eye Earth: both in the power sector, and in transportation, wind, solar, batteries, and EV are all superior technologies to the incumbent technologies that run on fossil fuel combustion. But not superior enough to easily render incumbent tech worthless. Value retention is 1. real, 2. a big deal, and 3. is very much in the way. This problem needs far more acknowledgment.

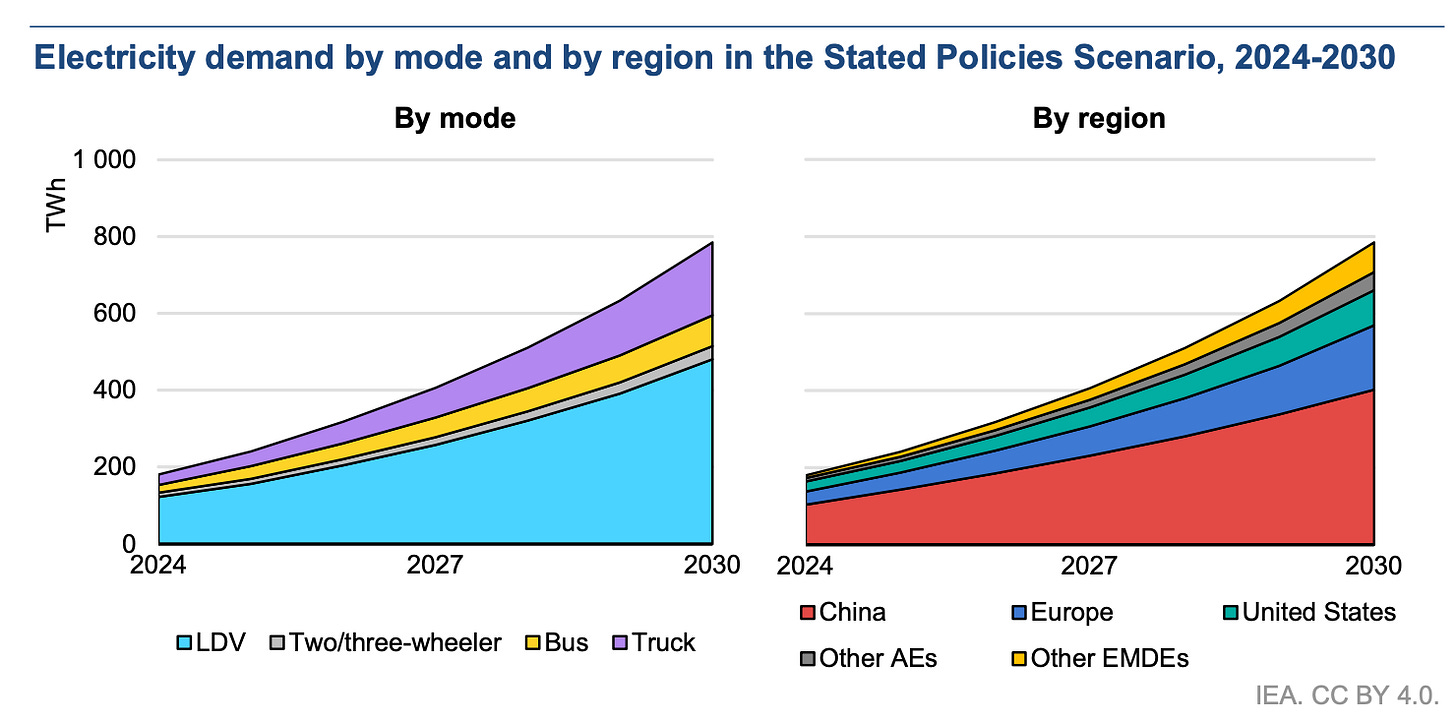

Finally, another way of looking at the slow pace of adoption globally is to note the IEA’s forecast for total electricity demand growth from EV by 2030. While it’s true that an EV uses at least 65% less energy to go one mile than an ICE vehicle, the IEA’s growth forecast is still exceptionally mild, rising only 600 TWh from last year through the end of the decade (200 TWh - 800 TWh). Scale and Proportion check: The world used over 31,000 TWh in total last year; and using a 5 year trailing CAGR is projected to reach nearly 40,000 TWh by 2030. This projection therefore from the IEA for EV driven power growth is so mild, it’s more akin to projections of data center growth, currently at roughly 500 TWh during the same period.

The reconciliation bill just passed by the US House of Representatives appears to be very much in the Reverse Robinhood tradition. As such, the bill would place not upward but downward pressure on the US economy, as capital is channeled towards upper income entities, while the middle class would see, in the aggregate, a contraction in funding for everything from health care to student loans. And that’s in addition to the new 10% tariff layer on all imports, which are leading to higher consumer prices.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cold Eye Earth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.