Dumb Growth

Monday 20 September 2021

Although the US market for EV is far behind China and Europe, Q1 sales soared in California. The US EV market continues to be plagued by a lack of consumer choice, and production hiccups. GM’s ongoing recall of the Bolt doesn’t help and it’s particularly damaging to consumer sentiment that safety issues are the primary problem. When the company warned Bolt owners not to park within 50 feet of other vehicles, that probably did some medium term damage to EV prospects, and confirmed suspicions that EV are not ready for primetime.

A recent New York Times article, however, claimed the biggest hurdle to EV adoption in the US is charging infrastructure. No, that is not true. This is a tired, out-of-date thesis that arose years ago and appears to be getting recycled. Indeed, the real story is that EV model availability ex-Tesla is only now appearing at scale in the US market. China and Europe are far ahead by contrast not only in variety of choice, but in affordability of choice. A model like the Hyundai Kona Electric was available last year and the year before in the US, but only at the highest priced model version. And this low-availability condition has only now begun to lift. New models, like the VW I.D. 4, today are not only available, but, at the various price points consumers require.

This may be one of the reasons that California’s EV market, which was far ahead of the rest of the country on the back of strong adoption of Tesla vehicles, is now going from strength to strength. According to data from CNCDA, combined electric and plug-in market share reached at 10.8% in Q1 2021, after notching an 8.1% share in 2020. (readers will recall that EV/Plug-ins have also now crossed the 10% market share threshold in China). This “lift” can probably be projected to the rest of the country, as we now look ahead to the next 12 months. Ford’s e-Mustang, while expensive, is doing well. And the blockbuster to come is the all electric Ford F-150: Automotive News reporter Michael Martinez toured the plant recently, noting quite interestingly that robotics are central to the model’s assembly line.

Financial market jitters arose in recent weeks with concerns about valuations as ripples from China’s real estate market dented the growth outlook. Cyclical stocks, which had dominated in Spring, struggled further. Names like Rio Tinto and BHP came under extra pressure as China’s demand outlook is receiving more scrutiny. Volkswagen, which is having a very good year, has seen its share price fall nearly 25% from the Spring highs. And other auto sector names like GM and parts supplier Aptiv are also off their highs of the year as the semiconductor shortage presses onward.

These machinations are largely noise, typical of post-crises periods. But China’s leadership is not helping. Clearly the actions taken against the large Chinese internet giants like Baidu and Alibaba have damaged sentiment for both international and domestic investors. It is easy to imagine how China’s economy was getting into position to rely on a thick layer of e-commerce sitting atop its more cyclical industries. Now de-fanged, it is not clear how China intends to proceed. Adding further to the problem is that Xi and the Communist Party’s long term goals remain opaque. Does Beijing intend to have an economy dominated by traditional, heavy industry forever?

After the great financial crisis of 2008, a bounce-back recovery globally in asset prices and a pick-up in economic activity resolved into a soft, recession-like period which did not qualify as a two quarter contraction but showed up in areas like Southern Europe with a crisis in Greece, and lagging sectors in the US economy. It’s not clear if China’s property market will trigger a similar set of ripple effects. But global equity markets are concerned about that risk.

The US offshore wind industry is finally getting underway as construction begins on Vineyard Wind. Over the summer, while based in Providence, I conducted an ongoing informal poll to gauge awareness levels of these developments and learned many New Englanders were either unaware or unclear of the timeline. That’s not surprising. Energy, outside of a crisis, sits pretty low on the attention spectrum. But the emergence of a new energy industry up and down the East Coast is going to bring a number of changes to the region—whether noticeable or not. | see: Vineyard Wind secures $2.3 billion loan, allowing construction to start.

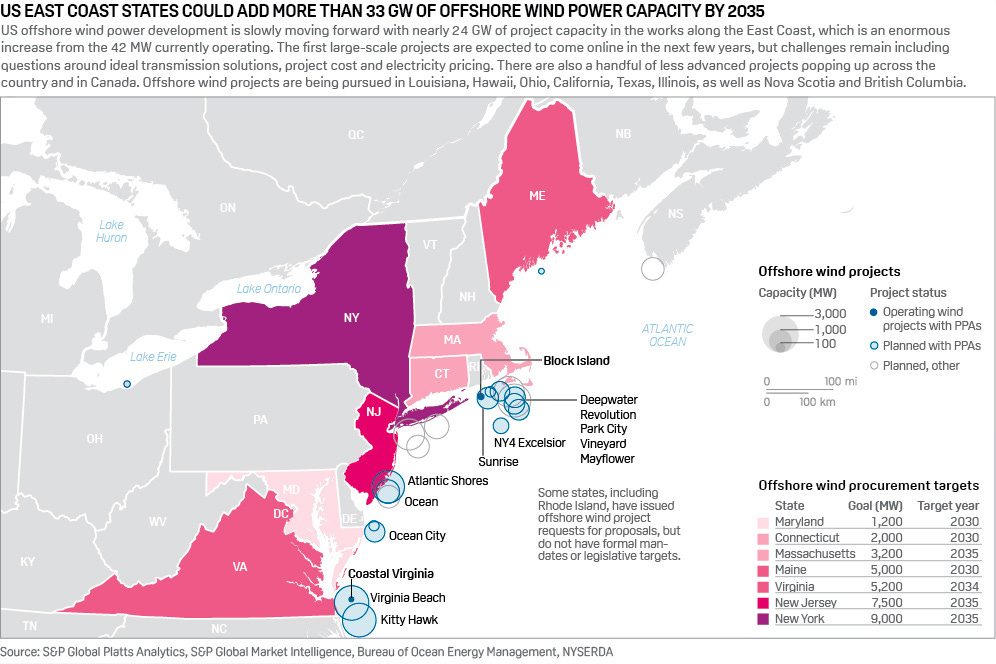

First, the public may not have grasped that at least 30 GW of new wind capacity will be deployed by the end of the decade. That is the equivalent of (nameplate) capacity of about 30 nuclear power plants. And while wind power doesn’t run 24/7/365 like a nuclear plant or natural gas plant, wind supply offshore is significantly more abundant (well, obviously). Moreover, a network effect has taken hold among the 8-10 states that will construct such massive offshore fields, which has ratcheted upwards the capacity pipeline from 12 GW to 30 GW. Why? Supply chain opportunities, and the effects that come from learning that “your neighbor” just increased their own offshore wind plans. As in Europe, we can speculate therefore that 30 GW is just the first course.

Below is a recent graphic from Platts (Spring, 2021) but the map continues to evolve as more states announce plans, correctly discerning costs will decline as deployment expands.

Second, large renewable generation is going to lift the investment opportunities in storage, especially as storage costs are falling more steadily now, and will fall further. In the western US, storage is now routinely paired with new clean generation and that will be no different on the East Coast. The EIA has recently pointed out that US storage capacity is set to increase by 7X, 1.65 GW to 12 GW, in just the three years from 2021 to 2024. And again, that is just the first course. Moreover, we are increasingly seeing storage scale up to something that starts to look more like generation itself. This is not to say that 4 hour storage—the current benchmark for lithium-ion grid batteries—is equal to generation but when you begin to deploy a number of these, you start to form a hybrid powerplant. There is a vast inventory of brownfield real estate on the East Coast too, largely a remainder of 70 years of deindustrialization. So, cities from Providence to New Haven to Baltimore will have easy land cost inputs to build, and site storage.

Finally, there are other applications and commercial implications as well. The arrival of utility-scale energy on the East Coast also means the arrival of digital energy that will increasingly be controlled by electronic devices at the level of the home, the car, and commercial and public buildings. Massachusetts and New Jersey are already far ahead in rooftop solar, for example, so the transition to controlling demand as well as supply is very much underway. But the key point is that variable energy, while seen historically as a deficiency, actually opens up other commercial applications that gather around the utilization of surplus power. For example, Avangrid recently made proposals to the US DOE to build hydrogen electrolysis capability in Connecticut, and referenced the future supply of East Coast offshore wind. It is easy to see why these two sources of supply and demand might find each other: electrolysis is still too costly, but wind power tends to produce at night when system demand is low. If you have a commercial application whose economics improve greatly by taking cheap, surplus power in off-hours, then you may be induced to site your operations near that opportunity.

Rising natural gas prices have grabbed headlines recently, and once again have brought declarations that the era of cheap gas is now over. The problem: North America has head-spinning volumes of recoverable NG. But that won’t solve near term supply and demand problems. Unfortunately for NG, if this price advance is sustained for a while, it will only swing the pendulum further towards renewables. Shayle Kann put it nicely:

Here in the 21st century Dumb Growth really should be off the table for US cities. But the post-war car-dependent approach looks very much alive, especially in the US West. Over the course of summer while traversing the country twice by car, I had an occasion to examine transport and real estate development in three potentially notable regions: Boise, Idaho; Omaha, Nebraska; and the Teton Valley. Both Boise and Omaha are spreading outward quickly along arms of development that look remarkably similar to post-war growth in Los Angeles. Boise in particular has myriad new highway overpasses that resolve into new corporate and housing-tract buildings that clearly thrive on unbounded prairie and rangeland. In a number of these, let’s call them off-ramp lands, the planning and zoning directive appears to have been as follows: build whatever you want, wherever you want, and we will build 4 lane and even 6 lane surface roads wherever necessary.

The long-term problems associated with this approach are now well established. Mostly, the front-end of this growth produces profits, and a moderately attractive setting to the first buyers when all construction is new, and the natural landscapes are still vibrant. This is precisely today’s portrait of Route 6 in southwest Omaha, which runs through very pretty, rolling prairie out by the Elkhorn River. Generally sited around Gretna, Route 6 has a large inventory of new apartment buildings that bear a “downtown” design, along with new malls that provide services. The point: none of it looks ugly and none of it looks underutilized, just yet. But give the area 20 years and the “strip” that was once shiny and new will likely suffer disuse, congestion, and will be seen most likely as a difficult part of the region in which to live. In the post-war era, that has been the fate of all such developments.

The mistake America keeps making, of course, lies in this constant roaming. Downtowns built in the early 20th century are abandoned for the suburbs, and now these are neglected too as the exurbs rise. Occasionally, brief migrations go countertrend and some moderately revived interest in the original downtowns takes place. (This finally occurred in Los Angeles, though downtown LA living is not exactly pedestrian friendly). But the constant roaming eventually cause cities to wind up empty handed, with a constellation of expensive problems—caused, in fact, by these dumb solutions. It’s not just that those good looking overpasses in Boise, with their friendly graphics, will fade in their appeal. Rather, it’s that they eventually convert into ongoing costs, subtracting rather than adding to local productivity.

It’s perfect, therefore, that a “Walmart billionaire” has a plan to build a fantasy city from scratch in the southwest desert. Notice the faulty assumptions behind such a plan: that it’s cheaper to build and sustain all new urban infrastructure far away from any existing city; that energy efficiency gains can best be realized in such a setting; that existing cities (with all their water, power, and road infrastructure already in place) can’t achieve more cost effective solutions; and that existing cities are not worth the investment. This seems to be a duplicate of the 20th century development model, but wrapped in an attractive rectangle of foil. Notice also: the appeal to novelty and the allure of The New.

This brings me to the third region of summer travels: the Idaho side of Jackson Hole, known as Teton Valley. This example is particularly useful, because the Teton Valley is experiencing hyper real estate price appreciation, has lots of available land to develop, and is very much on the radar of investors who see higher net worth individuals migrating to American mountain towns. In short, these towns are being suburbanized. And you have probably read such stories taking place everywhere from Whitefish, Montana to various towns in Colorado. Development in these places proceeds therefore in a very light regulatory environment: as such, the Teton Valley is thereby building itself a future collection of problems. You can already see the roads laid out that will become strips; already see the traffic congestion that will promulgate the argument(s) to build more roads. And here’s the best irony of all: the price level on the other side of the mountain range, in the Jackson area, is partly driving values in Teton Valley. An apt anecdote: the airport at Jackson is technically inside the national park, and is thus limited in the number of flights it will handle in any 24 hour period. Accordingly, celebrities and other high net worth individuals have increasingly utilized the airport at Driggs, and then take a caravan or chopper over the range to Jackson.

As a coda to this little essay on dumb growth, the Washington Post is running a terrific feature on South Carolina’s plans to expand highways. It’s an old story, a sad story often told, and one that America keeps telling.

The Biden administration declared a goal to source 50% of the country’s power needs from solar by 2050. To put that in context, both Texas and California are already reaching above the 25% level of electricity produced by combined wind and solar. The US as a whole is already at 10%, wind and solar. So, the 50% target is not as wild as it may seem, if we have 30 years to accomplish it. Solar will just get cheaper, and so will storage.

If you believe markets will get us there anyway, well, that’s very good news. If you believe only policy will get us there, well, the reconciliation bill is crucial. In truth, some combination of markets and policy will take us there. But I am not quite sure why the focus has to be on solar, exclusively. Cost curves in onshore and offshore wind are looking terrific, and offshore in particular has made great advances of late. For what it’s worth, it was tempting at one time to guess which technology, wind or solar, will win the race. That question now is moot. They both will.

No coal, no industrial revolution has been my take for years on the crucial input to this important phase of economic history. But of course, it’s more complicated than all that. Intellectual and scientific advancement was progressing quickly in the decades prior. And, human innovation around various energy sources, from wind to water power, also has to be seen as an important antecedent to the era. One of those energy inputs was peat, and here in this terrific essay by Davis Kedrosky, you can pick up some great data and key points in economic history, without getting dragged through an entire book.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.