Electric Candyland

Monday 14 November 2022

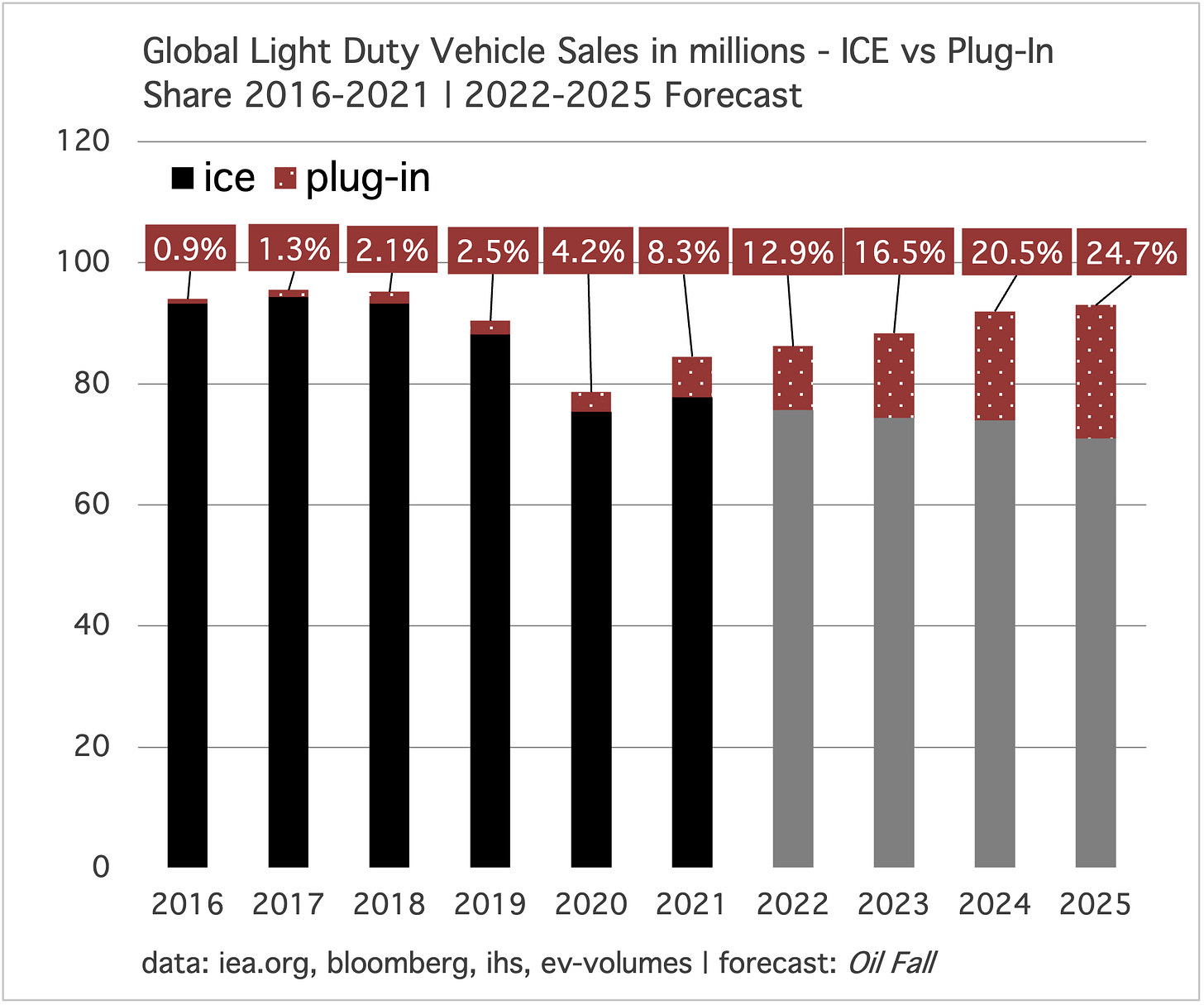

The 2023 update to the original Oil Fall series finds that global EV sales will reach a 25% market share in the year 2025. But constraints on battery capacity may make it difficult to keep scaling at such a torrid pace, in the back half of the decade.

Welcome to the Oil Fall update, Electric Candyland. The original thesis of the series, that fast growing, clean electricity would find its way into global transportation remains not just intact, but on a strong pathway. From Europe to the US, and especially in China, growth of wind and solar is so impressive, that this fresh supply of power absolutely overwhelms all new demand coming on to the powergrid, from new on-road EV. Perhaps at some point this decade, through the confluence of EV adoption taking place at much higher levels and some unforeseen supply chain problem with new wind and solar, there will be hurdles to supplying grid systems with enough power to meet the grand upsweep of electrification. But no such logjam exists today.

China remains the prime mover in this supertrend. The nation is not only deploying new wind and solar at a fast rate previously thought implausible, but the progression from 1.2 million EV sales in 2019 to 6.3 million EV sales this year is something rarely seen, perhaps only in markets for small, handheld devices. That this is unfolding in the car market is just completely off the hook.

That’s why the original Oil Fall series devoted an entire chapter to this exact risk. China Sudden Stop, released in 2018, explained that given China’s historical propensity to undertake supermax initiatives in infrastructure and industrialization it would behoove analysts to consider what might happen to electric car sales, should the country make EV adoption a matter of urgent policy. The potential was clearly evident, even if the country had sold “only” 777 thousand plug-in units in the year prior, 2017. The reason: impatience with the country’s air pollution levels reached a cultural flashpoint earlier in the decade, and despite sniping and critiques from outside China, it was clear that Beijing wanted to respond to the problem.

From 2018’s China Sudden Stop:

China consumes half the world’s coal, produces 25% of the world’s electricity, and takes nearly a quarter (23%) of the world’s total energy consumption from all sources. It currently has the largest vehicle market in the world, recently running at about 28 million vehicles per year (The US market is currently running near 17 million per year). In the same way California buys half the EV sold in the US, China buys half the EV sold globally each year. In 2014, China bought 188 thousand EV. In 2018, China will buy a million EV. By 2020, China may buy as much as 2 million EV––if so, EV sales in China will have risen a full order of magnitude (10X) in just 6 years. That’s insane. But it’s also a warning to those who would doubt China’s ability to single- handedly kick a global trend into an entirely new direction.

At the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, many of the displays during the opening and closing ceremonies seemed to highlight the mathematical realties of China’s population, in the intricacy and interlocking scale of those performances. Artistically, it was a way of saying “we can quickly escalate or de-escalate any trend by multiplying effects across our great number of people.”

Using the latest data through October, we can be pretty confident of where China’s EV market will land this year, somewhere around 6.33 million units will be sold. Note also in the chart that ICE sales are down nearly 29% since the peak in 2017, as China’s ICE sales move from the 28 million unit level in that year, to 20 million this year. As Electric Candyland rhetorically asks, what if instead of transitioning to EV, China was still trying to serve its entire car market with ICE? Answer: an unfolding disaster through increased petrol demand, and worsening air pollution. Here is a helpful framing: try to see China’s adoption of EV as a matter of survival.

The world will put nearly 11 million new EV on the road this year, representing a significant hit to future oil demand dynamics. While obvious, it must be said: without China, the rough and tumble dent EV are putting into global car markets would only be running at half strength. Although this is exciting, if not intoxicating, it is the general conclusion in the Oil Fall update, Electric Candyland, that global EV sales can keep chugging along for another couple years, scaling quickly, but may run into hurdles in the back half of the decade.

From Electric Candyland:

As the Oil Fall update goes to press in late 2022, semiconductor shortages for the auto industry are easing. But notice that these shortages knocked out the full potential of global vehicle sales for nearly two years. This is exactly the risk the battery supply chain faces. In late 2022, for example, global EV demand is on course to see nearly eleven million units sold. And the Oil Fall forecast, as seen in chapter 4 of this update, projects that both the total global vehicle market and the EV market grow into 2025, with 71 million ICE units sold, and 22 million EV sold. That doubling of EV sales is going to be made possible through three tranches of existing battery capacity: the base in China, the base built up by Tesla, and the new capacity that will come online in the next several years. The risk is that it’s still not going to be enough to keep scaling past 2025.

The Oil Fall update has not yet been put on sale, and is not yet available to the public. As a paid subscriber to The Gregor Letter, you will soon receive your personal copy for free through an email, with a download link.

The Oil Fall package contains two PDF files: the original 2018 series that bears a new, updated cover, and the 2023 update, Electric Candyland.

• Paid subscribers to The Gregor Letter: You will soon receive an email from terrajoulepublishing@gmail.com with a link to download the Oil Fall package from DropBox. No need to sign in to DropBox, no need to have a DropBox account.

• Previous purchasers of the Oil Fall series from online marketplace, Gumroad: You too will soon receive an email from @terrajoulepublishing@gmail.com with a link to download the Oil Fall package from DropBox. No need to sign in to DropBox, no need to have a DropBox account.

• Future paid subscribers to The Gregor Letter: When the Oil Fall package goes on sale all future paid subscribers to The Gregor Letter will get a free copy as part of the sign-up process.

Global oil demand has peaked, and is currently in the early stages of a potentially long plateau. That’s the other central conclusion of the Oil Fall update. But we must remember that peak, by itself, represents an initial achievement whose impact degrades over time unless it is followed by demand declines. And Oil Fall just doesn’t see declines happening any time soon. An array of forces, some old, some new, have lined up on either side of the supply-demand equation, and oil consumption thus faces a kind of standoff, potentially oscillating for another five to six years.

From Electric Candyland:

In the 20th century, whenever demand fell, so did prices, which rescued demand. That dynamic is not dead, but it’s greatly muted. While US production output is recovering nicely since its pandemic smackdown, the rate of the recovery is a tad slower. And importantly, OPEC does not seem to be concerned at all about weak economic growth or even the risk of recession. Saudi Arabia in a former era would have eased, like a central bank. Not now. Why? Because they understand. Yes, they now understand there’s no growth coming.

The era that global oil demand has now entered is going to drive everyone crazy, with its failure to either grow much again, or decline much. That’s because demand, supply, and price are in a standoff. The standoff comes mainly from organic forces that will suppress demand growth, but additionally from the industries’ response: making sure to never again over-produce. The demand outlook in the chart below is less a forecast, and more of an indication: oil demand locked into an oscillating standoff, as it loses market share to electrification, but retains its grip on legacy consumption, and dependency.

The Oil Fall update ends on a surprising note, concluding that further analysis of how electrification of transport will unfold is less compelling, now that the supertrend is underway. Five years ago it was still unclear whether sales of ICE vehicles would peak, and less clear how EV adoption would proceed. With these uncertainties out of the way, the intriguing aspects of speculation and analysis have begun to fade away. The big EV markets are all heading rapidly towards reaching 25% market share. Wind and solar growth is more amazing than ever. Not alot of mystery remains.

If you are a policymaker, or an analyst who makes policy decisions, a couple of things are about to become more clear. For example, do you really need to devote your energy at this point to making sure more wind and solar are deployed? The momentum wind and solar now enjoy would suggest they are off and running to the upside so strongly, it’s hard to imagine they need more help. And on the semiconductor, battery, storage, EV, and transmission side of the equation, we’ve also seen very significant legislation in the US that seeks to pursue all these capabilities.

Readers should pay special attention therefore to the chapter on Britain, in Electric Candyland, because the UK has actually added a significant piece to its decarbonization effort that breaks hard with the US, and many other countries around the world: a major congestion and emissions scheme that now looks down on the country’s largest conurbation, London. The UK now has all the clean power from wind and solar that California enjoys, has all the EV uptake acceleration of Europe, and is now building storage. But the twenty year congestion scheme in London has become a platform for a deeper squeeze on emissions, and the decline of London air pollution measured from any point over these past twenty years is impressive. One point that Electric Candyland makes about this policy is that excess and unnecessary car trips into London were themselves imposing a kind of tax on the entire system, and greatly added to the congestion that typically halted lines double deckers, idling while pumping out diesel fumes. The road charge scheme, and now the emissions scheme, reverse this tax, shifting the burden to those rightfully responsible. London essentially runs a carbon tax, distributing it through personal vehicles.

Imagine if California had such a scheme. Or rather, that’s what should be worked on. You see, a big part of the long plateau that Oil Fall sees in global oil demand comes from the fact that we’re doing very little about the existing vehicle fleet. Consider also that even in 2025, when one out of four global car sales is expected to be electric, the world will still be putting at least 60-70 million new ICE vehicles on the road. The Oil Fall series therefore sends the same warning this year that it did nearly five years ago, when it began to publish: peak fossil fuel consumption, while good news, doesn’t give way automatically to more good news. The IEA in its most recent WEO sees the bulk of fossil fuel consumption peaking this decade, for example. That’s great. But it says nothing about how hard it will be to achieve the declines, that most everyone expects.

—Gregor Macdonald