Energy and the Presidents

Monday 6 March 2023

Energy transition has spawned a populist myth that governments around the world are inhibiting production of fossil fuels. The climate community only wishes that were true. There are no efforts in Canada, Australia, the United States, Mexico, South America or elsewhere in the OECD where policies, new or old, are acting to meaningfully constrain fossil fuel production. And there are certainly no climate or ESG policies at work in the Non-OECD—in China, Russia, or the Mideast constraining production in these regions either. You really have to laugh at the idea that high profile climate figures like Greta Thunberg have dissuaded, say, coal production. The climate community just spent the last seven years believing global coal production and consumption had peaked, back in 2014. Nope. In 2021, demand reached back to near all-time highs, and global coal production actually did reach a new high. And so did natural gas. Oh, the constraints!

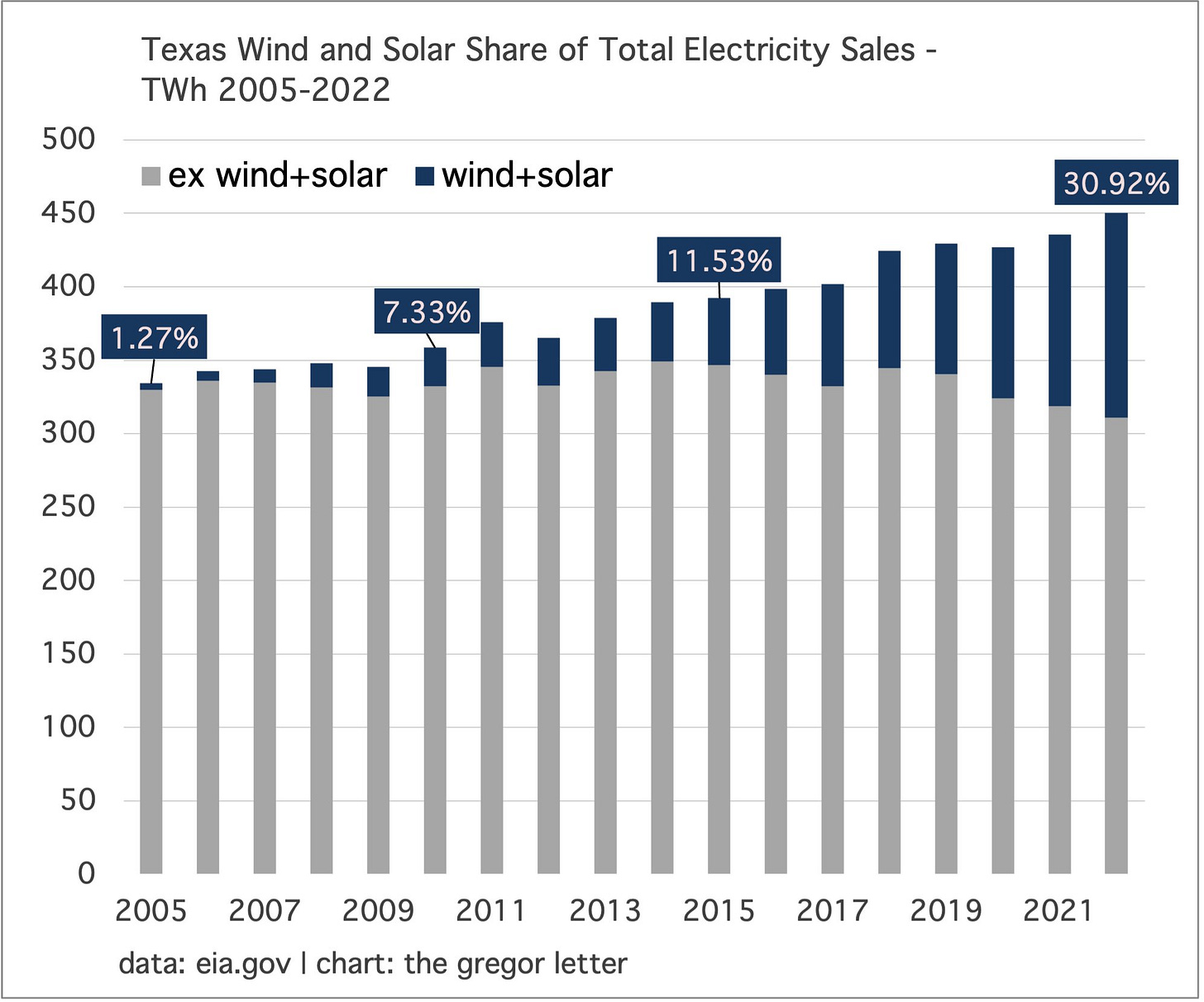

The myth draws most of its oxygen from the very real and robust efforts global governments have undertaken to incentivize production of clean energy. Wind and solar now provide over 30% of electricity in Texas, California, and nearly 20% of electricity across Europe. Global EV sales reached over 10 million units last year, or, one out of every seven vehicles sold. Universities and other institutions curtailed new investments in oil and gas starting a decade ago, if not longer. The bitter and aggrieved commentary that often comes from the oil and gas sector fails to recognize that global investors simply decided that more attractive investments lie elsewhere.

The myth really comes alive when you look at global petroleum production. Western free market economies like Canada for example, where discretionary climate policies are supposedly in full control, are seeing new all-time highs of production. The same story is taking place in the United States, where the only cause of a temporary pullback in petroleum production was from the demand collapse during the pandemic—not policy.

US petroleum production in 2021, as depicted in the chart below, was just 3% off the all-time high in 2019. But now, the EIA has just reported that total United States field production of petroleum did indeed just hit a new, all-time high in 2022, at 17.81 million barrels a day. (The chart showing new all-time highs in US petroleum production in year 2022 can be found not in this essay, but in the subsequent essay further down). Canada and the US, by the way, compose nearly a quarter of total global petroleum production.

Now look at Middle East production. Does anyone seriously believe that countries from Saudi Arabia to Iran, Iraq, and the UAE are on a new climate campaign to stomp out fossil fuel supply growth? Mideast production was down 11% in 2021, from a high in 2016. And how about Russia, where production was down 6% in 2021 from the all- time high in 2019? These regions are producing less for various reasons (war, politics) but mostly because demand growth globally for petroleum has slowed, and because western producers (supposedly in the vice-grips of climate policy) keep growing output! The irony is delicious.

With petroleum production hitting new all-time highs in Canada and the US—and with total global production of all fossil fuels near/at all-time highs—what is left of the argument that governments are suppressing fossil fuel production? Does one make the claim: even though global natural gas, global coal, and US petroleum production and US natural gas production are at all-time highs, well, they’d be even higher-er without government interference? Good luck with that.

One of the more amusing versions of this argument can be observed each quarter in the respondent survey of the Dallas Fed, in which participants complain bitterly that the Biden administration is destroying the US oil and gas industry. The Biden administration has certainly engaged in some harsh rhetoric about oil and gas. But the rhetoric is all for show. There are no policies, outside the normal course of regulations that have lumbered forward in the US for a century, inhibiting US oil and gas production. The US is now a robust exporter of petroleum products, and as important, is the new giant of LNG exports, as it takes the number one position this year from Australia. Today, the US stands as a global titan of fossil fuel production, and ranks second only to China as a producer of energy from all sources. Constrained? Not even a little.

Americans mistakenly believe political rhetoric governs energy policy, but the fact remains that the United States runs a free market energy system. And in a free market system, price and technology are in control. Correlations between the political perceptions of various Presidential administrations and actual, realized energy outcomes remain exceedingly low, and in many cases negative. Yes, the EPA (created by Richard Nixon!) has churned out regulations for a half-century and American presidents can certainly bend both the discourse, and the regulatory state, in their preferred direction. But it’s truly remarkable to consider how the last four Presidents, in this century, oversaw energy outcomes that blatantly defied commonplace public perceptions. And these were not marginal outcomes, but central, large scale outcomes. Consider:

• George W. Bush, not only from Texas but who had worked in the oil industry, oversaw a relentless multi-year decline in US petroleum production from 7.669 million barrels per day (mbpd) in 2001 to 6.783 mbpd in 2008. That’s an 11.5% decline over eight years. Global oil prices spiked to the highest levels ever, and probably played a role in helping to trigger the great recession.

• Barack Obama, who came to office talking about restoring train travel and the need to grow clean energy production—and who was often accused by the political right (see if this sounds familiar) of destroying US energy output—oversaw the largest increase in a half-century in US energy production from all sources. Fossil fuel production soared during the eight year Obama administration, rising from 56.612 quadrillion BTU in 2009 to 65.437 quadrillion BTU in 2016. America’s energy deficit collapsed under Obama, falling from a 24.2% deficit in 2009 to an 11.6% deficit in 2016. And under which administration did the first wave of new LNG export capacity get approved? Under Obama, with that supertrend kicking off in 2014.

• Donald Trump came to office promising to deregulate and did indeed make good on that goal. Output of oil and natural gas continued to grow strongly, and Trump oversaw the actual moment of flippening in the US energy deficit in 2019, when the US deficit went from red to black. The big surprise however was that Trump was not able to do anything for the coal industry, a major reversal of expectations. US coal production continued to fall, from 774,609 thousand short tons in 2017 to 535,434 thousand short tons in 2020. The continued collapse of coal consumption was even more dramatic under Trump, falling over 33% from 716,856 thousand short tons in 2017 to 476,693 thousand short tons.

• Joe Biden came to office as the most vocal, aggressive US executive on the need to take action on climate change. His own rhetoric, and especially the communication from many members of his team on the topic of oil and gas, has been searing. And he and the Democrats have followed up on this posturing with bold legislation that spurs further the growth of wind, solar, batteries, and new energy technology. And yet, there has been no meaningful federal legislation that curtails the output of US oil and gas—both of which just reached (again) all-time highs. That’s why the flippening in the US energy balance sheet, moving ever more deeply into the black in 2021 and 2022, will surely steamroll onward. And US petroleum production, which suffered a hit from the pandemic demand collapse globally, has taken a very standard 12-24 months to not just recover, but reach a new high. A classic example of the free market, not policy, in full control.

What are some commonalities to the realized, rather than the theorized, outcomes from the four administrations in this century?

• Inheritance. George Bush inherited an oil and gas landscape that had plodded along without much investment, as oil had been cheap for many years. When prices rose globally, US production was stuck in low gear, unable to respond. Barack Obama inherited the technological advances in tight oil production that finally allowed supply to respond to price. Donald Trump inherited a coal collapse supertrend as natural gas and wind+solar were already unstoppable by the time he got to office. Joe Biden inherited a new LNG export industry that had grown large enough to actually play a geopolitical role in Russia’s European power play.

• Lack of Interference. All four presidents did far, far less than they may have claimed (or their detractors or supporters claimed) to influence the energy outcomes that unfolded during their administrations. Mostly, they simply didn’t interfere. Obama didn’t invent fracking, and he didn’t stop or interfere with it either. Trump did nothing to slow wind and solar growth and that trend was underway regardless, with significant momentum. Biden has done nothing, other than harsh words, to interfere with US petroleum production growth.

• Longer Timeline Effects. George Bush as Texas governor was instrumental in getting a new wind industry off the ground, and two decades later, Texas is an empire of wind production. As president, Barack Obama unleashed both a new LNG export industry and rapid growth in US wind and solar, but each of these outcomes saw their critical mass flourish mostly after he left office. Donald Trump rolled back fuel efficiency standards for cars, and that will take time to correct. Finally, the big bang energy infrastructure bills passed under Biden, already getting traction, will have huge impact, but more visibly in the second half of this decade.

Americans are certain they support a free market system in energy. But when prices go berzerk at the pump, or natural gas prices spike as international buyers bid up LNG, suddenly they have a case of The Sads. Americans would never support the formation of a state-run oil company like Aramco or Petroleos de Venezuela. They don’t want interference in oil company profits. But they are equally confused at the fact that no matter how much petroleum or natural gas supply grows domestically, this supply has almost no effect on price locally, unless it affects price globally. When prices misbehave, it’s as if Americans do indeed want a federally owned oil company to subsidize energy prices for them. Just can’t admit it!

The gordian knot grows more vexing still, for example, in reactions to the Biden administration’s clever tactic of using the petroleum reserve to temporarily blunt war-induced high oil prices. The US may not have a state owned oil company. But it does have state owned oil. And the successful deployment of that oil also seems to have given some the sads. What exactly do Americans want, therefore, from their energy system? Your guess is as good as mine, but all signs suggest that whatever is impossible, whatever is the thing no one can have, well, that’s the thing they want.

Wind and solar growth in Texas is super strong but so far has only covered marginal growth, without much impact on legacy sources. This is not an attempt to negatively spin a good story. And it must be pointed out, large new volumes of solar capacity are coming to Texas. Rather, the Texas example is instructive to an emerging problem in global power, which is growing so strongly that wind and solar might cover marginal growth, but are not as yet in position to attack fossil resources, forcing them into decline. Back to Texas: it looks like a strong bet that wind and solar are, finally, about to direct legacy sources into decline, below the 300 TWh level. Awesome. But readers should consider the time it took for that outcome to appear.

The IEA forecasts that renewables, hydro, and nuclear will nearly cover all the growth in global power generation the next three years. In 2013, this would have been astonishing news. In 2023, it feels less so. The IEA is on firm ground in one sense: global nuclear generation is finally about to make a move forward. The US has a new plant coming online, France is restarting capacity, and there’s some new capacity coming in Asia. Where the IEA view feels less encouraging is that it’s relying not only on hydro growth, but it’s leaning on biomass too in order to arrive at its encouraging outlook. The Gregor Letter is not a fan of biofuels and biomass, and is especially not keen on categorizing them as renewables. Biomass has thin energy content, and to extract that content requires extra energy. Moreover, burning wood pellets to create electricity is hardly clean, and is rather archaic.

The IEA forecast also says little about 1. where we will be in covering global power demand after this three-year period is over, and 2. the developing situation with natural gas growth. The IEA acknowledges that electricity growth is expected to be strong for years to come. Well, of course. The current project is to move as many services and needs over to the power system, which is readymade for clean energy. Something to watch: if nuclear does play a key role in suppressing fossil fuel growth in global power generation through the year 2025—which would be the first time global nuclear has grown in twenty years—what story will we tell ourselves? Will we continue to incorrectly claim that wind and solar alone can get the job done?

Heat pumps just keep on pumping. If you’re still not clear how heat pumps work, and if you’re especially baffled how they create heat during winter, you will enjoy this excellent explainer by Casey Crownhart in the MIT Technology Review. Crownhart finally addresses what many others have failed to adequately explain: the heat pump’s internal refrigerant, a liquid, converts to gas (boils) at a very low temperature. Meanwhile, in ongoing heat pump news, a new study concludes that efforts around using hydrogen as a heating fuel—which is prospective—are not likely to pan out given that heat pumps are already 2-3 times cheaper than such proposed hydrogen systems. This may be less of a critique of hydrogen’s future potential, and more of an insight into the learning rate: global heat pump production is soaring on the back of demand. And that means heat pumps, while still expensive, are going to fall in price.

Many US cities in the post-war era were irreparably damaged by the intrusion of freeways. Elsewhere in the world, the freeway-removal movement has been going on for two decades, as cities from Asia to Europe discover that commerce, shopping, and the revival of urban neighborhoods can all flourish once specific arterials are removed. The above photo of Providence, RI, for example shows the waterfront area after the removal of a short-section feeder road that once connected to I-95. While Providence remains scarred and bisected by I-95, the new pedestrian bridge opens to a significant amount of new land in downtown, now starting to be utilized.

Now the US Department of Transportation is taking the next step, with a Reconnecting Communities program. While certainly just a beginning—there are far more planning grants than capital grants—the program obviously seeks to unleash a wave of road reconfigurations and removals. Let’s hope that happens.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to Dropbox Shop.