Floodgate

Monday 13 June 2022

Global solar capacity has now crossed the terawatt threshold, a sign that the solar age has arrived with unstoppable momentum. Deployment of large infrastructure does not proceed at the pace of digital adoption for obvious reasons. But once a certain critical mass is achieved in costs and supply chains, even heavy networks of pipelines, port capacity, and other networks of conveyance can start to achieve rapid completion timelines. And so it is, now, with global solar.

One terawatt (TW) is equal to one thousand gigawatts (GW), and a single gigawatt (or two) is roughly the size of your average coal or natural gas plant. So an easy way to think about the world’s new terawatt of capacity is to frame it as one thousand new utility scale solar plants. That represents a very, very significant volume of new natural gas or coal plants that will not be built. And the kicker: we went from 500 GW to 1000 GW in just under four years.

Many casual observers of solar have by now absorbed its supreme competitiveness— the relentless price trajectory as solar has melted downward through multiple cost floors to become the cheapest new power source on the planet. What’s less talked about is the speed. The speed of solar. Doubling in less than four years, at such scale. Frankly, that does approach the speed of digital adoption, which is the most frictionless product uptake category in history.

Just to be clear, it takes alot more effort in the physical world to mount a solar array than it does to download a fresh copy of Microsoft Office. But you get the point: even solar optimists did not think we were so near in time to such doublings. In the US for example, solar (along with wind and storage) is now starting to crowd out all others for market share of new capacity. This trend is inevitable on a global scale of course. And when BP releases its statistical review next month, we’ll learn more.

In 2019 BP pivoted notably in its outlook for global oil, seeing the end of demand growth after 2025. It is not an easy time to have a conversation about oil demand, given that price is spiking and there’s a legitimate supply side story made worse by geopolitical pressure. But as readers understand, demand growth is poor, and getting worse. In BP’s most recent update, published in March, their 2019 view is maintained. There is no growth after 2025 and scarcely any between now and 2025—just an aggregate 2% over six years 2019-2025. Importantly, BP’s driver for zero growth is unsurprising: the end of road fuel demand growth.

The Biden Administration signed an intriguing executive order removing solar tariffs, and in particular boosting the manufacturing of heat pumps. Yes, heat pumps. That may sound twee if you are not familiar, but heat pumps are a super efficient way to lower the costs of winter heating and summer cooling. As readers are aware, The Gregor Letter is a big fan of demand side solutions, pointing out that the US has (successfully) pursued supply side solutions for decades while only lightly touching demand. A heat pump does use electricity, but it exchanges hot for cold air, or visa-versa, and can have a big impact on a building’s annual energy consumption. Daniel Cohan of Rice University has a good write-up on the executive order, which engages the Defense Production Act for heat pumps. He writes:

Pairing use of the Defense Production Act with customer incentives, increased government purchasing and funding for research and development can create a virtuous cycle of rising demand, improving technologies and falling costs.

The federal level action is also a kind of win for Bill McKibben, who cleverly used his high profile to call for action on heat pumps way back in February in his piece Heat Pumps for Peace and Freedom.

Soaring petrol prices, and perhaps a new resentment at oil dependency, is driving the public off roads and motorways and onto public transport in the UK. Since March, bus ridership among those taking at least 1 ride per week has risen 12%, and cycling levels have doubled, according to data collected by the Financial Times. According to the same article in the FT, the average cost of filling up a vehicle with petrol has now crossed 100 GBP. At recent exchange rates, that equates to $123.00. Meanwhile, in the US, the average price per gallon of gasoline has now risen to/above $5.00 nationally for the first time ever. As many likely understand, it’s not just that oil prices are high. Product prices—diesel, gasoil, jet fuel, and petrol—are even higher comparatively as refining capacity comes under pressure, and product shipping routes have been disturbed by Russian sanctions.

One way to see the current situation in petroleum—a nasty combination of soaring prices with poor demand growth—is that it’s a kind of natural experiment for how a supply-side constriction policy would work, if you thought this was the best way to move economies more quickly off oil dependency. Not very pretty, is it? Demand side solutions to wean ourselves off oil are less painful by comparison, but politically difficult because they require leaders to persuade the public to voluntarily take the pain. A draconian supply-side regime by contrast is interesting to consider in this light. It is more akin to a royal edict, or the imposition of a supply shortage by dictatorial fiat. Because Russia plays such a key role in how our present situation arose, it is with some irony to consider that current oil prices have reached the level, frankly, of rationing. Rationing and shortages were of course a normal part of economic life in the Soviet Union.

Rationing however is rather Hobbesian. Nasty, brutish, and in this case not exactly short in duration. You have to admit though, it’s unsettling how effective high oil prices are becoming—short of causing a global recession. (More on that topic to follow). Elevated oil prices are not unlike a carbon tax, or a London road charge, or congestion charges, or a surcharge on energy consumption. The difference being, in road-charging schemes a premium price is not applied to the whole of society, but rather only to those who still choose to commute by car at rush hour, or who choose to not use public transport. In the difference lies the problem: high oil prices may be effective at killing discretionary petrol consumption, but may also be effective at killing economies too.

If you think oil prices are challenging today, they may get worse when the latest EU sanction package begins to take effect later this year. A critical feature of global oil supply is that it relies on seaborne trade volumes, and those ships rely on the insurance industry. So far, Russian seaborne oil has continued to find buyers in China and India, which is another way of saying every Russian barrel that makes it to market is a barrel those buyers don’t have to buy elsewhere. But later this year, that too is going to change.

The latest EU sanction package on Russian oil exports very effectively applies itself to the insurance lever, and will bar EU insurance companies from covering Russian seaborne oil with a policy. Without insurance, VLCC (very large crude carriers) cannot move, because their cargo value is simply too high for buyers to take on uninsured risk. Accordingly, that is going to more fully embargo Russian oil not just from the west, but everyone else too. Ben Cahill at CSIS in Washington has a terrific and detailed review of the EU’s 6th sanction package, with particular focus on the insurance lever.

The EU is quite clever here, but perhaps too clever, because this will once again hurt western economies far, far more than it will hurt Russia. Or, put another way, these sanctions will indeed hurt Russia, but at the expense of crippling far larger western economies. If you agree that the west is effectively in a war with Russia, harming yourself, if not disabling yourself voluntarily, would not normally be part of an effective war strategy.

California’s EV market continues to soar, and is quite obviously now a factor in the state’s weak petrol demand. According to data from CNCDA, total plugin sales in Q1 of this year reached 73,138 units out of a total market of 425,215 sales, or 17%. That’s a European level of market penetration, and very impressive.

One additional factor often not talked about is the market share of non-plugin hybrids. Data note: most researchers in this sector agree that non-plugin hybrids are not likely to survive the transition to plugin hybrids and pure electrics, so they are not often considered in projections. However, it bears mentioning that in the short term, California is still selling enough of these that when they’re added to EV plugin figures, they take the market share up from 17% to 28%. Again, the best forecast is that these legacy hybrids will not survive (much) the full transition but it’s useful when considering the failure of California’s petrol market to rebound much in our post-pandemic.

California has not updated its petrol consumption data since the 4 April issue of The Gregor Letter, Oil Dependent. But it is equally interesting to note that even as EV sales soar, total vehicle sales are slumping in California just as they are nationally.

One possible explanation: with the knowledge that EV are the future, and that petrol prices are volatile and punishing, buyers may be keeping their ICE vehicles as long as possible, having already made the decision that their next vehicle will be electric. The very idea that one would go out today and purchase a new ICE car, thus locking in dependency on oil for the next 7-12 years, is both comical and absurd.

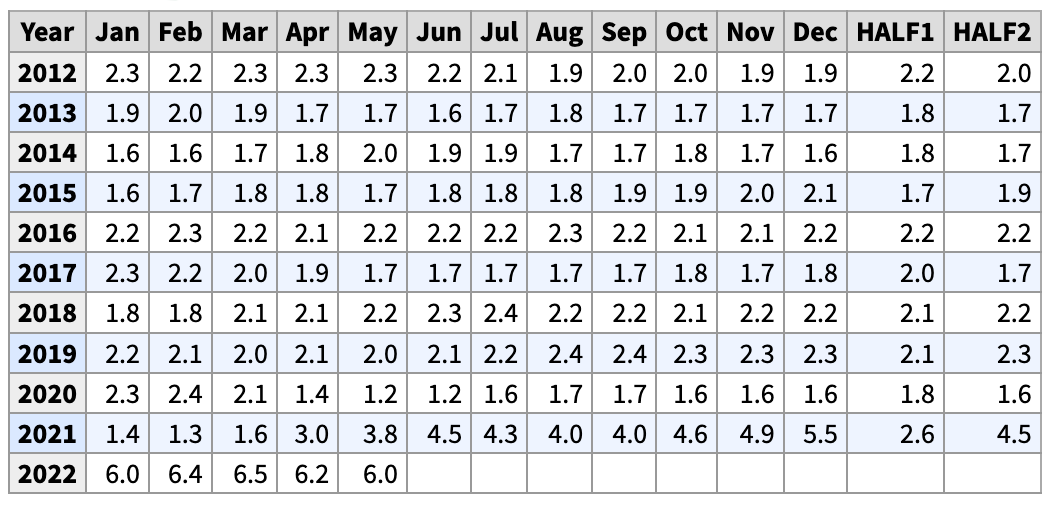

Friday’s release of the US Consumer Price Index took the emerging narrative of peaking inflation and smashed it to pieces. There was nothing encouraging at all in the report in which both headline and core CPI came in above not just market expectations, but various forecasts from banks in the Federal Reserve system, like The Cleveland Fed. Indeed, many of the points made in the last letter, Rollover, are now in question—especially the behavior of the two year treasury yield, and the US Dollar index. Markets immediately and correctly started pricing in an even more aggressive tightening cycle: equities fell, the two year treasury yield rose, and the US Dollar strengthened.

The CPI report is a flurry of different readings, based on large baskets of components, and which tracks both annualized, quarterly, and month-over-month inflation data. It’s no wonder that the report is confusing, because it generates multiple, concurrent discussions across all these time series. If one was to fish in those waters for one, hopeful data point it could plausibly be found in the annualized core reading, which fell to 6.0% and looks like it’s trying to eke out a declining trend this year. Core = less food, and energy.

The problem is that the report’s headline number and month-over-month numbers came in higher than expected. To make matters worse: these readings were supposed to get relief from the shifting baseline, as this year’s data is now increasingly based on last year’s data, when that data had started to lift. But we didn’t get that relief either. Inflation is worsening, not getting better, or even flattening.

Unfortunately, the CPI opens the floodgate to more aggressive Fed action and brings us closer to answering the common question: will the Fed have to hike rates far enough to cause a recession? The most probable answer now is yes, absolutely. Ben Bernanke in his 1997 paper showed that central banks tragically capitulate to fighting energy-driven inflationary episodes, only to learn later that hiking rates into such events roughly doubles the effect of tightening because higher oil prices eventually act like a tightening on their own. Since that time, many other academics have explored this tricky equation, and unsurprisingly found over and over again that at certain price thresholds for petrol, for example, consumers begin to withdraw, if not dramatically withdraw, from other spending. This marginal propensity to consume, importantly, can even influence consumers who are not in actuality being negatively impacted by high petrol prices. Plain terms: even the rich see their consumption behavior influenced.

Here is the most helpful idea I can offer to readers: there is a moment in these energy shocks where the inflationary effects undergo a conversion, and fossil fuel price spikes start to grind out a strong, deflationary pulse. We have likely arrived at that moment.

If global macroeconomic conditions are about to worsen, then the terrible year for long duration US treasury bonds is about to brighten. While the US Dollar index is back on a strengthening path as it anticipates additional rate hikes, and the yield on the two year treasury is doing the same, the US long bond showed some reluctance to follow these changes, even though it too remains very roughed up over the past year. Why might that be? Easy peasy: if the current economic mess is about to worsen, and the Fed continues to be aggressive because of the energy shock, then the US long bond space will see that coming as we flip from an inflationary domain to a deflationary domain. In the chart below, the yield on the ten year treasury is “retesting” the highs. Readers are encouraged to watch this financial instrument closely to gauge how the market thinks the next 6 months will proceed.

Just to remind: the US economy has consistently shown an ability to not only transition, but transition quickly from inflation to dis-inflation as there is no more powerful force systemically than a broad shift in US consumer demand. Unless you think this is the 1970’s (which would be an error in thinking) then a long stagflationary outcome is simply out of the question. The economies of the OECD, demographics, and a whole range of other features of the global economy are radically different from the 1970’s.

The high-profile American writer Ezra Klein is bringing much needed attention to an issue dear to The Gregor Letter: congestion pricing. Ezra does a terrific job explaining both the win-win of congestion pricing, but more importantly to his broader points, how byzantine regulations and thick, calcified layers of government oversight make infrastructure solutions nearly impossible in the US.

It’s hard to think of a liberal goal congestion pricing doesn’t serve: The people who drive into Manhattan are richer, relatively speaking, so it’s a progressive tax; the people who take mass transit are poorer, so it funds public infrastructure for those who need it most; cars belch out more pollution per passenger than trains and buses, so it’s good for both the environment and public health. One study found that Stockholm’s congestion pricing plan cut ambient air pollution by 5 to 15 percent and sharply reduced severe asthma attacks in children.

But New Yorkers are still waiting. Congestion pricing isn’t technically complicated. It doesn’t require major new infrastructure. It’s largely a question of hanging sensors on poles. But I’m told that the likely launch date for New York’s congestion pricing program — which, again, passed in 2019 — is now sometime in 2024.

To come full circle: The US is a domain that has wasted decades trying to implement energy and transportation solutions that don’t offend anyone. As a result the US has wound up empty-handed again, a full fifty years after the last true energy shock. Demand side solutions were available in every year of those fifty years, and yet we are still dragging our feet. It’s always dangerous to say this time is different, but fingers crossed, maybe the hour has finally arrived.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.