Front Page Fed

Monday 3 October 2022

The US Federal Reserve’s inflation fighting campaign has reached the front page. If FOMC meetings, dot plots, and breakeven rates across maturities are too esoteric for the public to understand, what better way to advertise the Fed’s effort? Back in the day, President Ford launched a Whip Inflation Now policy, and famously wore a WIN button. No, that didn’t work. But it demonstrates the correct understanding of the situation: you want your inflation fighters to appear as contestants, before a crowd of spectators, as if on a playing field. For a sphinx-like institution such as the Fed, with its long record of dry verbiage and techno-speak, that means getting loud. Loud enough to be heard on the front page. The current members of the FOMC are surely very, very pleased with that headline - With Jump in Rates, Fed Shows it Means Business on Inflation.

The Fed’s inflation campaign however reached far beyond domestic headlines last week when the United Kingdom suffered a moment that typically arrives in small, emerging market countries. Both the currency and the government bonds of the UK experienced a mini-crash. While the announcement of a new and economically inappropriate tax and spend policy by the Truss government was the proximate cause of the drama, it was really a culmination of an overly strong US Dollar—on a rampage the entire year—that laid the groundwork for the troubles.

The US Dollar has begun to act like a bulldozer, crawling menacingly through the landscape, smashing buildings. As the Yen, Pound, and Euro decline against the US Dollar, a second inflationary shock is delivered to those economies. Worryingly, this is the dark mechanism by which the Fed’s inflation fighting campaign, if sustained at its current pace, would extend far beyond the front page and threaten to deliver a global financial crisis. Strong, secondary inflation shocks transmitted through this currency destabilization would trigger a collapse of demand in countries outside the US. And eventually, if not quickly, that hit to demand would rebound to the US.

When the Fed aggressively hikes rates, it’s not like the Bank of England hiking rates. When the Fed does it, the tightening is global. Because we live in a dollar-based system for world trade, and because the dollar is the most common reserve currency, the Fed is putting the squeeze on the global economy too. And doing so, it must be said, in a time of war. That’s why the Fed’s hiking campaign has started to receive vocal pushback from such figures as Wharton’s Jeremy Siegel, and DoubleLine’s Jeff Gundlach. (Even Greg Mankiw has weighed in, via an endorsement of Paul Krugman’s similar take). The Fed, in their view, is not even taking weeks, let alone months, to review the results of their work. Ahead, they just plow.

The Fed is winning its campaign! Public expectations of US inflation continue to fall. You can see this expressed in market expectations, and also in broader reporting, like this week’s University Michigan survey, which continues to show the public’s view of inflation is falling. Does the Fed really need to provoke a series of small, international crises—to fight inflation, at this point? That would risk outcomes that could travel far beyond the task at hand. When the Bank of England had to step in and buy UK gilts this week, that should be interpreted by everyone, and the Fed too, as a signal that the Fed’s effort to get themselves on the front page has not only been successful, but has now gone too far.

Nearly half of the world’s oil market is composed of countries and regions that have long since passed peak oil consumption. The chart below covers the year 2021, and the share of consumption each region accounts for, in the total global market for oil. The regions gathered on the left side of the chart, in purple, are the post-peak regions, composing 48.5% of the market last year. One the right side, the pre-peak regions. The story of the past decade: the right side of the chart has had to grow ever faster, to make up for the lack of growth on the left side.

There’s a nice little insight too, in this equation: if you think you are doing your part for climate to simply halt further consumption growth of fossil fuels, you’re not doing as much as you assume. Steady consumption of oil that’s no longer advancing, but is not declining either, provides a nice stream of dependable demand for the oil industry, granting it freedom and flexibility as it seeks out growth in other regions. The left side of the chart, while no longer growing, provides this stability. Want to disrupt that game? Get your oil consumption to finally, finally enter decline.

A fast transition to renewable energy would unleash massive, economic savings. But, you knew that already. A fresh study published last month in Joule lays out the tantalizing learning curves we can expect to continue in four key technologies: wind, solar, storage, and electrolyzers. One of the study’s authors, J. Doyne Farmer, appeared on the Volts podcast, hosted by Dave Roberts. Give it a listen. Again, while much of this is already known, what Farmer and his co-authors appear to have updated are the learning curves themselves. And they’ve made a confident claim: none are ready to fade in intensity, just yet. That’s useful, because it quantifies better the distributed savings that will arrive over time, into the global economy.

The lower cost and higher efficiency of renewables—looming systemic impact on the global economy—was addressed in my 2018 e-book, Oil Fall, in the third and final chapter, Waste Crash. International research groups have for years run estimates of the heat waste involved in fossil combustion, which is a decent proxy for the financial losses incurred with combustion. Renewables are exciting two ways, in this regard. One, they get cheaper to produce the more you produce them (learning curve). Two, once deployed, they deliver far more efficient energy per unit constructed, precisely because they avoid combustion (not to mention far fewer moving parts, 24/7/365 supply chains, and high operational expenditures).

Here is a copy of that chapter, Waste Crash, readable for free to users at DropBox (no account required).

The Oil Fall series is finally about to update, and should appear before year end. The pandemic entirely disrupted the Oil Fall update, as it threw an enormous wrench into the continuity of oil supply and demand. Moreover, it was unclear for some time whether policies would succeed or fail around the deployment of new energy. The pandemic also disrupted the car market. And, EV adoption and its global rate is a key component to the Oil Fall series.

All currently paid subscribers to The Gregor Letter will receive a free copy of both the update, and a free copy the original three-part serial. So, if you were thinking of buying the original, please don’t. :-)

Global oil consumption is simply not going to recover to the 2019 highs. Literally nothing since the Russian invasion of Ukraine suggested global demand would rise high enough to meet those levels. Worse, the economic risk outlook has remained poor, steadily, for months—and is once again now worsening. As The Gregor Letter has pointed out previously, a bullwhip effect in supply-and-demand combined with a major geopolitical event to create an illusion, which less sophisticated observers swallowed whole: that there was some kind of structural energy shortage. No, sorry. There is no oil shortage outside of the normal challenge the oil industry experiences, and will always experience, after an economic crisis. It was like this after 2009 as well: oil prices soared not long after to $100, when the global economy could hardly absorb such prices.

Was there a problem in 2019 delivering over 100.56 million barrels per day to global consumers? No, no problem at all. So why is there a problem now, in 2022, delivering 99.69 mbpd to global consumers? The pandemic, obviously. And the war. And the sanctions. Yet the socio-political world thinks there’s some nefarious, deus ex machina explanation like mandated ESG investment guidelines, or social hostility to oil. “We can’t drill when global leaders are using mean words, yes really mean words, against the industry.” Which is funny on a number of levels, especially considering that US production is once again near all time highs, and will exceed those highs next year.

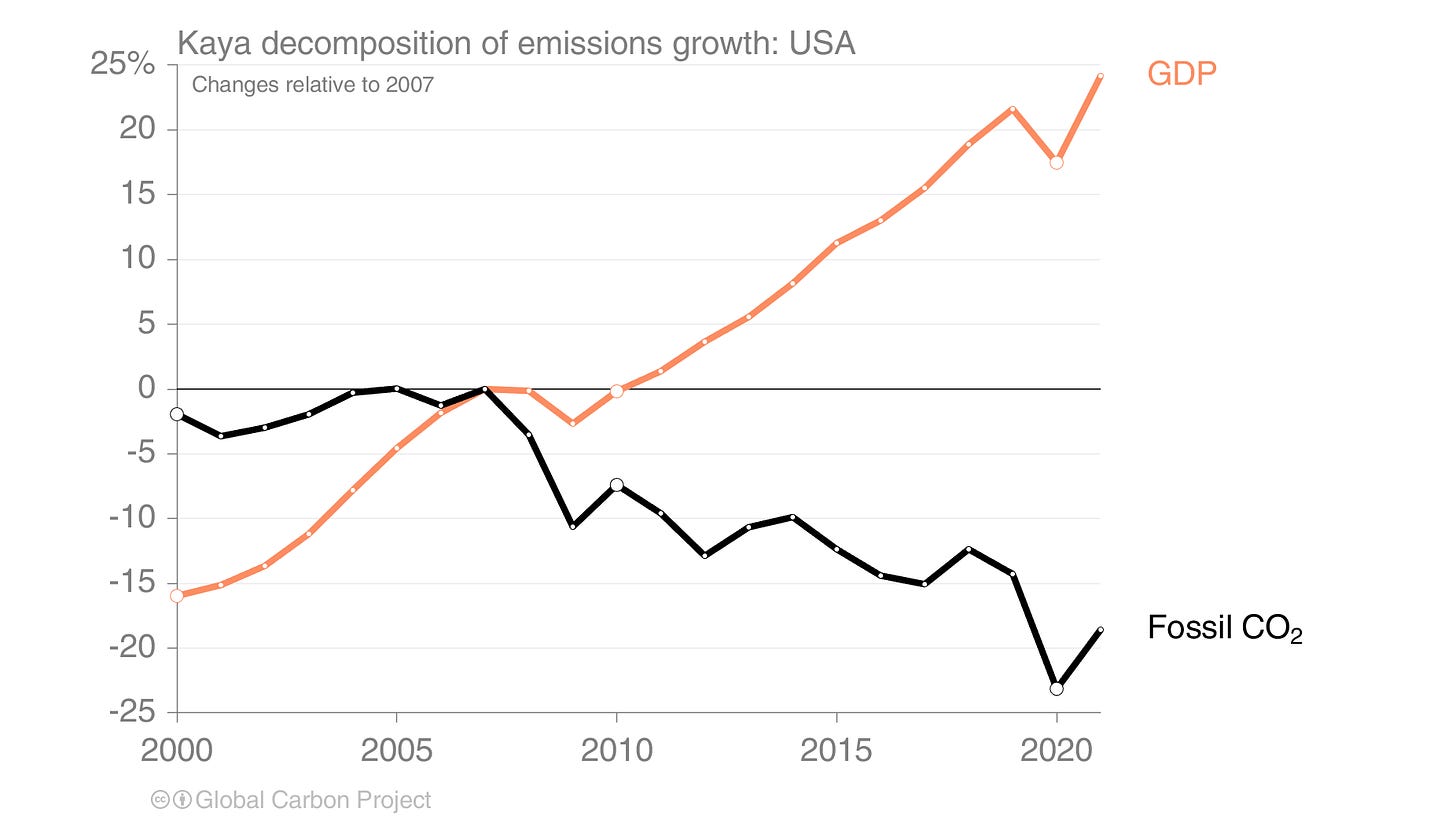

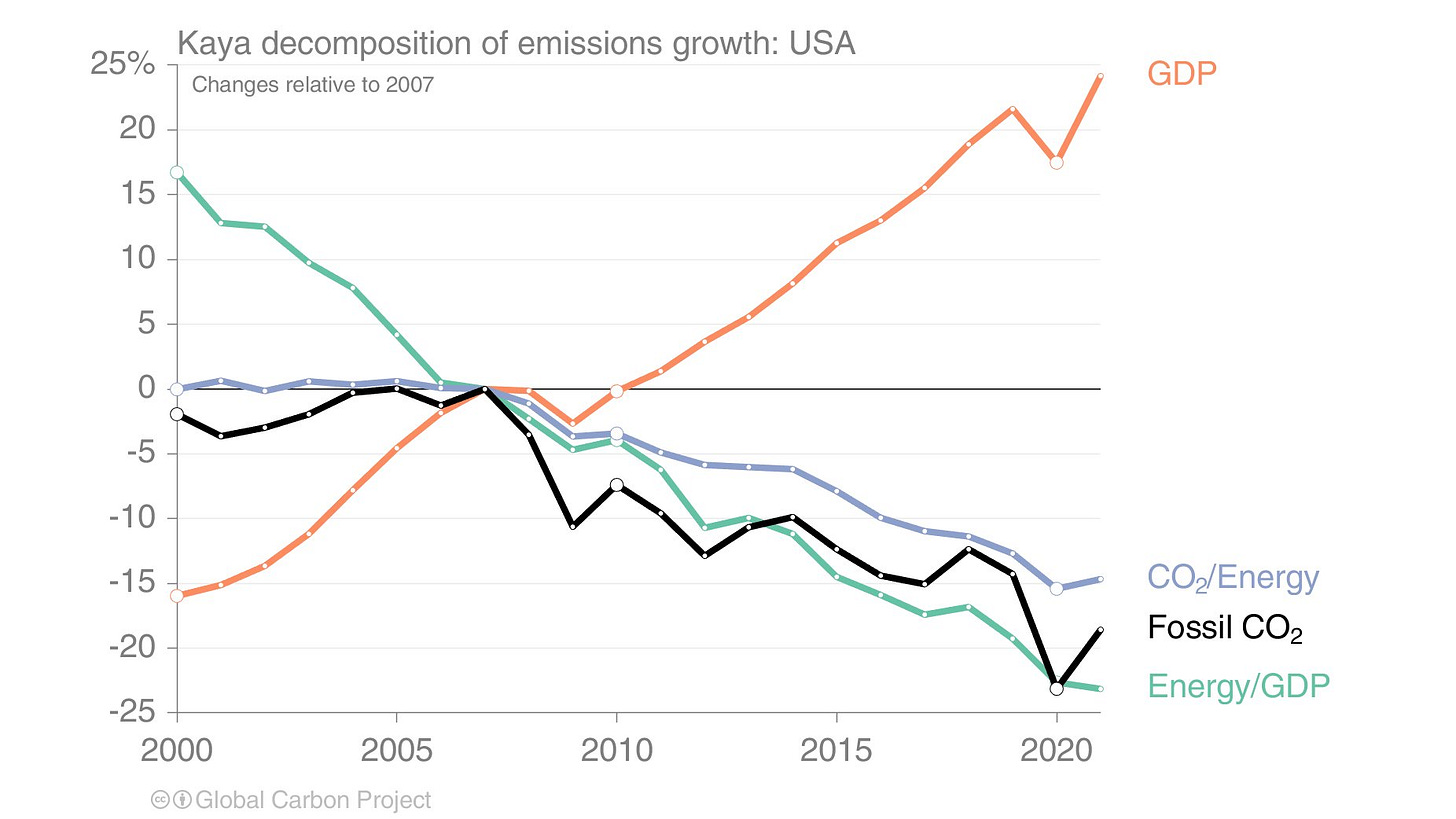

The US economy is on a steady decarbonization path. And no, it’s not because of offshoring. The bulk of US deindustrialization took place in the back half of the 20th century. Not this century. So you can’t use offshoring to explain the astounding progress that’s occurred in the US over the past decade. Glen Peters of CICERO, in Oslo, has a nice thread on this story. He begins with this chart:

US GDP is increasingly composed of intellectual, and digital output. Even so, the US remains a giant of global manufacturing—though this sector is now much smaller in proportion to the totality of US GDP. So the decarbonization trend is not entirely drawing breath just from trade in software and electronic devices. In fact, the US continues to manufacture everything from autos and drilling pipe, to aircraft and specialized industrial parts. Many who serially criticize GDP as a useful measure seem to dislike the fact that the nature of a country’s GDP changes over time. But that is just basic economic history. It’s a feature, not a bug. We were never going to remain a nation of farmers, nor a nation of factory workers. Today’s GDP is every bit as “real” therefore, as the GDP of those previous eras.

Most exciting is that as we decarbonize, the amount of total energy we need to produce GDP also declines. As readers know, more efficient energy goes hand in hand with less energy required to produce a unit of GDP. In the chart below, the green line shows the declining volume of energy needed to produce GDP. And in the United States, the energy we do use has far lower CO2 output. Basic rule: removing combustion from the system is the same as removing waste. It’s a climate argument. But it’s also an economic profitability argument.

2019 was most likely the peak of global oil demand, and an increasing number of analysts are starting to converge on that view. The latest is David Fickling, an Australian based journalist with Bloomberg, who also happens to have a real talent for storytelling. Fickling’s new view relies on a two-pronged approach that considers not just decarbonization in transportation and the adoption of EV, but also global central bank policies that are putting upward pressure on interest rates, and thus downward pressure on global growth. Fickling’s twitter thread starts here.

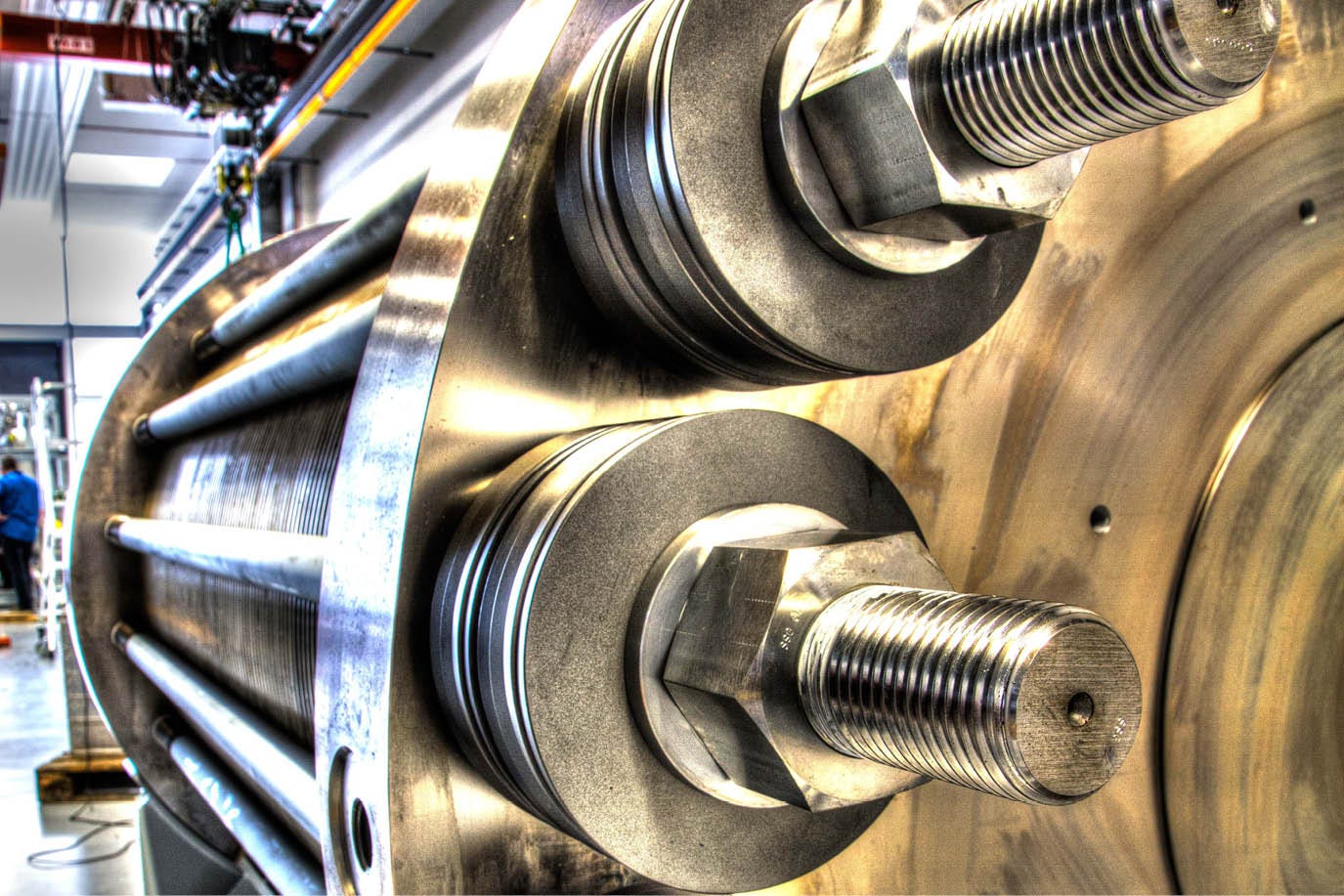

We should start paying closer attention to the hydrogen space and its basic building block, the electrolyzer. Electrolysis is the method by which we will make not gray hydrogen, or blue hydrogen, but green hydrogen—using clean electricity. The hurdle so far has been the electrolyzer price tag, a large and expensive piece of capital equipment. But if we started manufacturing electrolyzers at scale, the prices would drop and the cost to produce a kilo of hydrogen would become competitive. And that would be a very, very big deal. The HYBRIT project, for example, already showed that hydrogen could be used to decarbonize the production of steel. And you should be aware that the US Department of Energy is not only pursuing hydrogen aggressively, but clearly knows precisely which knob to turn first: getting hydrogen supply co-located with hydrogen demand.

The hydrogen potential is staggering. Worldwide, for example, natural gas turbines have been installed in many industries as sources of high-powered electricity not only to drive operations, but to perform industrial processes. Well, alot of these can be retrofitted to burn hydrogen instead. Further potential has been spotted in short-haul aviation, short-haul trucking, shipping, fertilizer production, and energy storage.

Some basic facts about hydrogen. First, hydrogen is not an energy source. You need energy to make hydrogen, and hydrogen then becomes a carrier for that energy. That’s fine and all, until you run into that little problem in energy physics, which unsurprisingly holds that if you expend more energy to make hydrogen than you get back in return, well, you are now behind not ahead in the game. That’s the current challenge in making green hydrogen. All the capital equipment needed to make clean power (wind, solar, hydropower, nuclear) and then the electrolyzer itself.

Here is what’s coming, however. First, the cost of electrolyzers is going to start declining. And then, when we deploy electrolzyers in locations near to steady demand, it will be critical to run them 24/7/365 in order to make the return on investment favorable. Let’s give a practical example, one that we will likely see in the next decade: hydrogen operations at airports. Air Alaska is working with ZeroAvia to install hydrogen powered engines on its short-haul prop planes. By installing an electrolyzer at Seattle and Portland airports, many of the short-haul flights in the region Alaska Air covers could load up on hydrogen continually at SEA and PDX while flying routes across the Pacific Northwest. Moreover, the quantity of hydropower and windpower already in the local grid mix in the Pacific Northwest is high. Eventually, these electrolyzers could be powered in addition by combined wind, solar, and storage systems. Such an outcome would have profound implications for jet fuel demand. Now apply this same set up to Europe, where short-haul flights are the norm.

Hydrogen’s biggest hurdle today is that unlike natural gas, or electricity or oil, or coal, it lacks a distribution network. There are no hydrogen pipelines, per se. So there’s no readymade hydrogen hookup that a newly established factory can plug into, no obvious means to create adequate supply outside of building new infrastructure. And that gets very expensive. Remember, the power of incumbency is that the world outside your operations is set up to deliver your product. If you produce oil, or electricity, or millions of other products, the world is set up to get your offerings to market. Not so with hydrogen. We are early, therefore, in the necessary ecosystem to make hydrogen viable. But governments understand this precisely, and will invest to solve the gap. Yes, it’s damn exciting.

—Gregor Macdonald