Going Global

Monday 19 October 2020

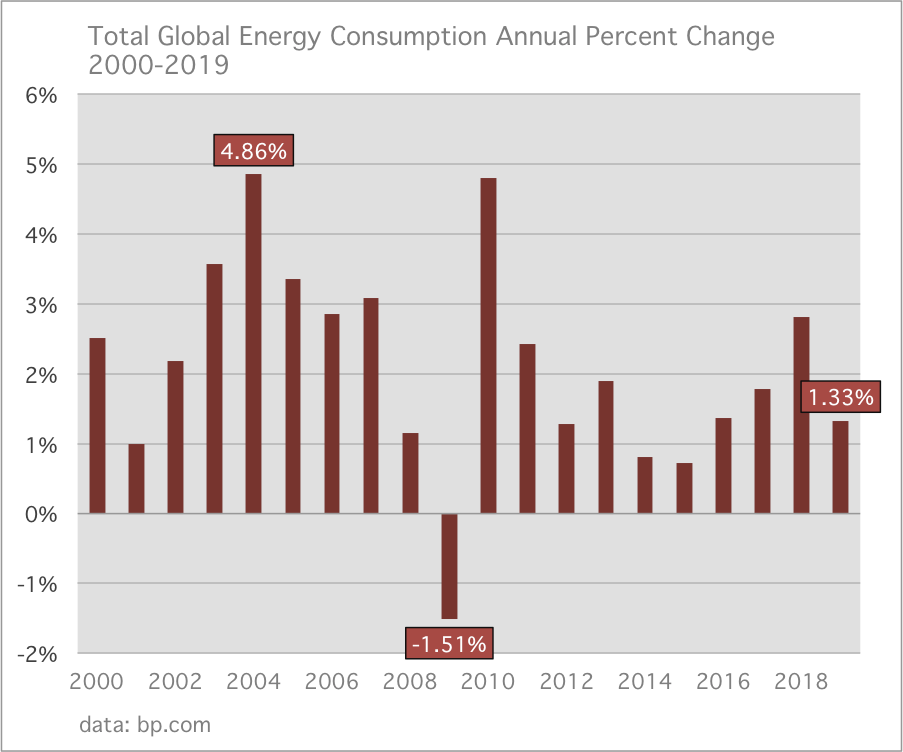

The growth rate of global energy consumption has slowed significantly, over the past decade. While it’s too early to draw a singular conclusion about the step-down in annual growth (after all, the post recession environment made for a messy ten year period) we can more confidently assert the next few decades will articulate this slower trend more clearly. The crucial factor: transition to renewables will voraciously strip out the waste from combustion.

Helpfully, energy agencies are starting to aggregate these energy savings into their longer term forecasts, as the world moves towards renewable-driven electrification. In the just released World Energy Outlook (WEO) the IEA in Paris projects that primary energy consumption will rise by another 18.6% from 2019 to the year 2040, under the Stated Policies Scenario, which projects the world advancing on its current track, under currently implemented or intended policies. This advance occurs under a compound average annual growth rate (CAAGR) of 0.8%. However, under the Sustainable Development Scenario, global primary energy consumption actually falls by 9.6% to the year 2040, at a CAAGR of -0.5%.

A couple of themes come to mind. From now until the year 2040, the energy business will increasingly be understood as the energy efficiency business. If primary energy consumption is to be regarded as the market, or really the total addressable market (TAM), then the energy business will be forced to address a declining TAM, and the market will demarcate along very bright lines between losers and winners. Tired: pipelines. Wired: power lines. Tired: seaborne commodity volumes. Wired: domestically sourced electricity. Tired: boilers. Wired: turbines. Tired: the auto repair, mechanics, and parts industry. Wired: OTA software updates to EV.

If we had to identify a top-down, macro theme for energy transition, we might say that energy is fated to become algorithmic. Electricity is more suitable to digital measurement, and distribution. And in a world with a declining TAM, optimization of the market that remains will be crucial, and profitable.

Global solar growth is poised to explode higher, and even the IEA now accepts this inevitability. Calling solar the new king of energy the IEA sees global solar capacity more than doubling to the year 2030 under current policies, and potentially tripling or even quadrupling under more aggressive policies:

A handy way to think about global solar growth is to understand the period before the world deployed 100 GW in a single year, and the period to come, when we will lift above 100 GW of annual growth. Global solar growth has risen 100X since 2004, and 10X since 2009. But the last three years have seen a flattening of growth, right around the 100 GW level. We’re about to break out, however.

Despite 2020’s emerging brand as the quintessential annus horribilis, most forecasts for this year are currently centered around 110-120 GW of new solar growth. That’s incredibly persuasive to the argument that solar will power through even the most severe economic disruptions. After all, oil consumption by contrast will fall by at least 7% this year (if not 10%) and myriad business sectors across the world will take years to recover. And yet, here is solar, ready to chew up the landscape like a bulldozer.

Looking to 2021, forecasts are coalescing around 150 GW of growth, and here is where the doublings start to get very exciting. As recently as 2015, even those professionals most bullish on solar growth were doubtful the world would see 100 GW deployed in a single year before 2025. Now we are in position to see the market bolt ahead from the current three year base, rising to 150 GW next year which then opens up the pathway to the first 200 GW year before 2025.

While finding a sturdy relationship between solar growth and solar industry profitability can be elusive, largely because solar is in a deflationary boom phase where rapid cost declines flow very quickly into market prices, it’s worth noting, for example, that the leading name in the US listed solar ETF offered by Invesco, TAN, is a maker not of panels but of solar system parts and components: SolarEdge Technologies. And it can’t have escaped most investor’s attention that TAN, as currently led by SolarEdge (SEDG), has bolted higher of late, rising nearly 50% from early September. The surge is rational, but is not without risks….

…More broadly, playing for an investment green boom is now very obviously a trade that’s been put on, in anticipation of a big policy change coming from the Biden administration. While this makes sense, there are two risks to consider (among many) to such an investment strategy. The first is that for any notable Green New Deal program to roll out, Democrats must not only win the White House (which is now highly probable) but they must also win the Senate. While the path to a 50-50 Senate is also highly probable (Dems pick up seats in AZ, CO, ME, and NC while shedding a seat in AL, for a net +3 gain) it’s still quite uncertain how much beyond 50 seats they can secure. Moreover, the Biden campaign has played with its cards close to the chest, so to speak, on the looming question of next year’s policy rollouts and which initiatives will take precedent. What if a new administration decides to tackle voting rights and voting modernization first? That would be a highly defensible priority, given the sorry state of voting infrastructure and laws in the United States. Alternately, what if the administration tackles the pandemic first, with another plain vanilla stimulus plan? That too would be defensible, but it might also serve to put off a Green New Deal package until later, at a time indeterminate.

Overall, readers outside the United States would be well served to remember that Democrats as a group tend to bog themselves down in a tangle of intellectual complexity, with a tendency to overthink myriad, competing initiatives. If Republicans tend to unite behind singular campaigns, Democrats often fail to optimize their policy sequencing. Moreover, once in power there will arise rather predictably an internal argument within the party over spending and deficits, with older and more senior Democrats more persuaded that deficits are dangerous. And these tendencies towards indecision are likely to be compounded by the fact that the Biden campaign has really been defined as a collection of various policy intentions, with no discernable theme beyond a restoration of decency, and the sought after termination of the Trump era. Perhaps this opaque posture will work to the Democrats’ advantage. But it could also complicate the declaration of a mandate, even if they roll into office on the back of a landslide.

Addendum: investors focused on Europe are also compelled to consider an ECB induced round of greentech and climate investment. But gears turn slowly in the EU, and everyone seems to be waiting for the signal. Bank Nordea suggests we might be getting closer.

The Gregor Letter is raising its forecast for next year’s oil consumption growth, but the change is mostly a base effect. As highlighted in the 21 September issue, Oil Old and Tired, it’s become necessary to increase next year’s demand rebound because this year’s decline is likely to be as steep, if not steeper, than most forecasted. Readers will recall that after the pandemic began, The Gregor Letter forecast that global oil demand would fall by a very hefty 10 million barrels per day (mbpd) in 2020, compared to 2019. Since that time, IEA, EIA, and OPEC have steadily moved in this same direction. Look, for example, at OPEC’s latest: now forecasting this year’s demand will fall by 9.47 mbpd. IEA Paris and EIA Washington have also juiced their decline estimates.

You can also take a signal from traditional GDP forecasts that have started to guide downward as the pandemic rebound continues to flatten out, putting pressure on Q4 2020 GDP both in the US, and globally. To summarize, the pandemic triggered a number of moderately severe demand forecasts for 2020 that started to look aggressive as an economic rebound took hold. But the rebound has now stalled, and faces the lack of new stimulus here in the US. Accordingly, 2020 is going to be just as bad for oil demand as originally feared. And The Gregor Letter is sticking hard with its 10 mbpd decline.

But next year is looking much better—mostly as we recover from a very low base—but also because a Biden administration so very clearly represents fresh rounds of stimulus and confidence inducing management of the pandemic. Accordingly, The Gregor Letter now forecasts 5 mbpd of growth in 2021.

Shares of British Petroleum fell to a 25 year low in London. In US Dollar terms, BP shares fell to lows not seen in over 35 years however. The company’s value has been cut by 50% this year alone. The bleak future for the oil and gas industry calls to mind the work of Harold Hotelling, who observed that producers of non-renewable resources all face a constant decision: whether to extract their resource slowly, in order to capture its appreciating value in the ground, or alternately, to extract their resource more quickly when prospects for investing the proceeds in other assets is more favorable. I think we can now say without reservation the market understands oil assets in the ground are either going to stagnate in value, or decline in value. Assuming that is true, producers should sell as much of their resource as quickly as possible, and devote that precious capital elsewhere.

The theoretical disagreement between MIT’s Andrew McAfee and LSE’s Jason Hickel, over the issue of green growth and material decoupling, continues. In a very long blog post published last week, Hickel expanded his ongoing critique of McAfee’s claims, and it appears he may have landed some blows. Frankly, it does appear that McAfee’s thesis, while right directionally, has often been supported by overreach. (The Gregor Letter has been following this conversation for several months. | see: Green Growth, 29 June 2020). One constructive way through the disagreement—and perhaps a way to the other side of the overall question—is the following suggestion: it is perhaps too early to make claims about growth decoupling from material consumption on a global level, because the data is too new, too young. It is not the time, just yet, to declare this empirically. However, as already shown in the first part of today’s newsletter, we are almost certainly on the cusp of such a change. Growing global GDP, while primary energy consumption actually falls, is going to happen. Outside of the energy sector, demand for other commodities will continue to rise along with population growth, modernization, and growing incomes. However, because energy is the common input to all production, these processes too will see a broad slowdown in overall costs, which are of course a proxy for resource extraction.

The Gregor Letter is changing its base case economic forecast, and bringing forward a more pronounced recovery into early 2022. Accordingly, the second half of 2021 will contain much of the positive economic data and optimism that the base case originally envisioned for first half of 2022. This effectively means the pandemic’s dampening effect will mostly run over two years, instead of three. The reason for the change: The United States is going to resume its global leadership role under a Biden administration, and will torch the path forward on pandemic management and economic investment. By mid to late 2021, it will become clear that the US is ready to face the decade to come, and will do much to shape it through science, energy technology, rational trade policy, and climate initiatives. This will not be a particularly friendly moment for a government like Britain’s, however, whose own dalliance with populism and xenophobic voodoo will increasingly be viewed as an outlier. Washington and Europe are going to get closer again, and if, for example, the ECB and other European governments are still hesitating on investing more heavily in new energy infrastructure, the sea-change coming to the US will likely tip those scales. China meanwhile, which has largely escaped scrutiny under a vacuous and theatrical tariff initiative under the Trump administration, will probably have to face more substantial tests from an administration that actually knows what it’s doing. One way China could ease those tensions: by joining a refreshed EU-US commitment to green growth. Perhaps, we may even see the first shoots of some carbon taxation in global trade—a trial phase, perhaps, with a very light footprint. Regardless, when China sees common agreement forming between Washington and Europe, and accepts that the US is no longer in feral mode, they will not want to be left behind.

While it’s too early to forecast the path of the employment recovery, the stock market is clearly anticipating an industrial led push, and many of the names that might be associated with such a trend have started to perform better. That said, market leadership continues to favor work-from-home names, especially in technology. But those names may see momentum decelerate significantly as the hope for a broader recovery gathers confidence. Accordingly, while a period of potentially intense uncertainty could dominate the scene as we head into the US election, and maybe for a week or two after, we should anticipate that an incoming Biden administration will make its economic plans, or at least some basic version of those plans, clear during the transition period. Cautionary remarks notwithstanding about habitual Democratic indecision, it will be in the Biden administration’s strong self-interest to kindle animal spirits as early as possible, to create some runway for when it actually takes office, in late January.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

Photos: 1. Downtown Portland Oregon, 2017, Gregor Macdonald. 2. Graphical history of various British Petroleum logos.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.