Goodbye Inflation

Monday 28 October 2024

We know enough about inflation to predict it won’t be returning anytime soon. For over three decades western policymakers mostly fought off deflationary pressures and were barely successful in their effort. That it took a global pandemic—with its collapse of supply chains, and waves of stimulus money—to finally trigger a supply-demand imbalance tells us everything we need to know about the risk that inflation returns anytime soon. Without a grand, coordinated effort taking place at scale, any new bouts of inflation just can’t occur, leaving the underlying deflationary supertrend to carry onward.

The world has been grappling with a deflationary trend for over 30 years now. The factors are numerous—everything from the fall of the Berlin Wall and the formation of the modern European Union, to the rapid uptake of productivity enhancing software, manufacturing automation, and offshoring. And even now, the world has still not run out of very low cost labor that keeps being integrated into the global workforce. If you live in the West, you are often exposed to stories of quickly rising cost of living in cities like London and Los Angeles. But these are mere islands in a world that holds vast inventories of cheap land and real estate. Indeed, all high-cost Western countries are beset with large post-industrial regions which continue to see population loss, and declining property values.

To understand the foundations of a deflationary trend, it’s important to have a handle on the common shape of infrastructure and supply-chain development in economies. To condense this unwieldy subject to a simple proposition: when your society gets past the upfront investment costs to erect public transportation, bridges, pipelines, information networks, and institutions of expertise, the cost to deliver the next unit of X tends to either fall, or not rise much. A good way to illustrate the downward cost tendencies of such a landscape is to consider its opposite condition, as seen in such eras as Gold Rush San Francisco during the 19th C, when the riches flowing from the newly discovered gold fields landed in “the city of San Francisco” which at the time was a barren outpost, and barely had any functioning services. Gold rush workers sent their laundry on ships to be processed in China, and prices for food, alcohol, or hotel rooms were crazy high. Think: what would be the price of a banana on the moon?

Today we’ve created not just markets in everything, but often instant, electronic markets in everything. You can hire help, start a business, file forms, and secure supplies almost effortlessly now. Even obtaining actual physical goods has become lightning fast. The classic example is that most people are within 15 minutes of a petrol station, where the next unit of energy can be purchased without a fuss.

The pandemic upended this established system, remaking the world into a kind of protean 19th C San Francisco, where no one was available to man the stores—hence, no stores. That the pandemic offers such a clean, clear test of inflation’s threshold is enormously helpful, because the pandemic revealed that the hurdles now are very high if you want to trigger and sustain inflation. Indeed, although inflation was a global phenomenon during the pandemic, the US literally kept adding jobs and expanding its economy right through and past the peak of inflation. Yes, that’s right: inflation peaked above 9% at its high in 2021, and fell steadily as the US economy and the workforce expanded.

Inefficient, less developed economies have a terrible time controlling inflation because the critical mass required to propagate efficiencies is unrealized. Indeed, in contrast to the now antiquated theory that a full employment economy sparks inflation, it’s robust labor markets that help control it. When workers finally returned and revived output, inflation started to fall.

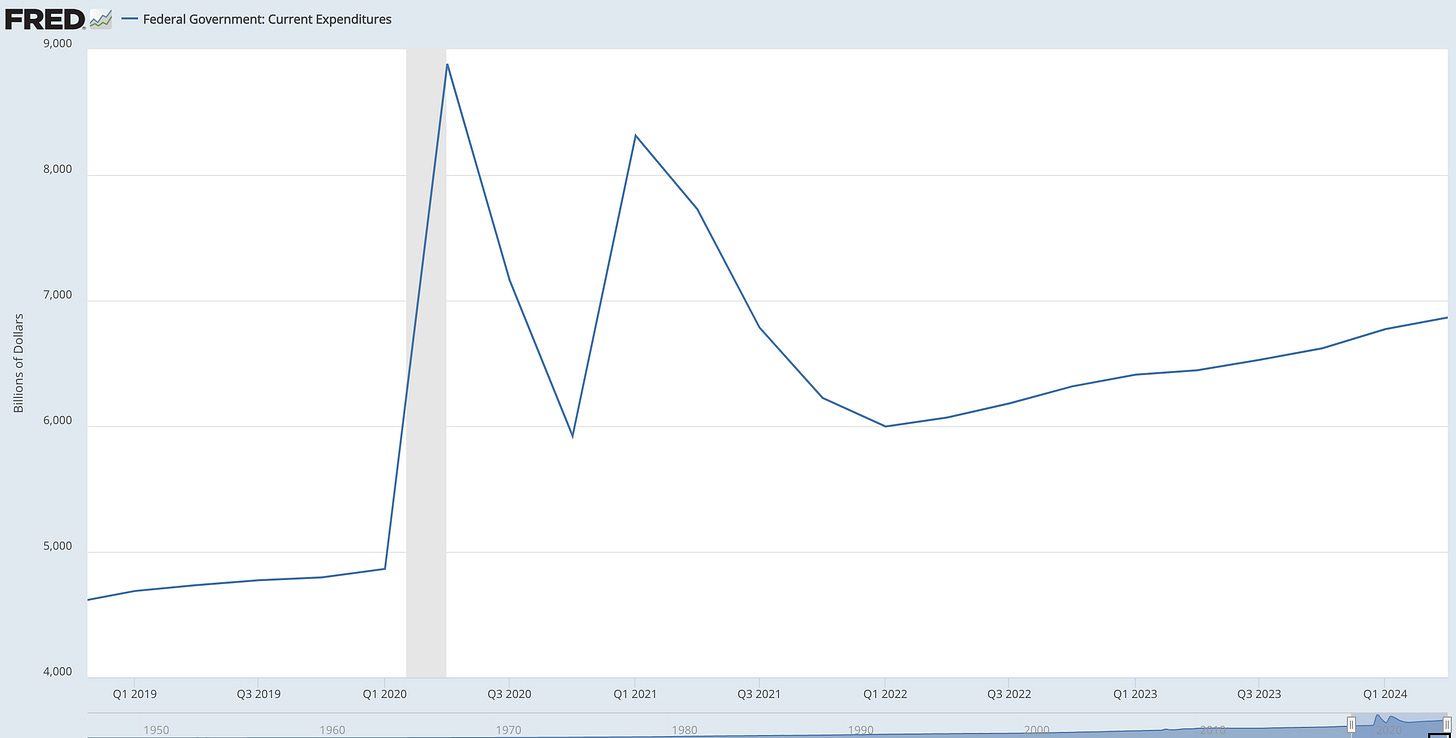

The politics of inflation remain as nasty and incoherent as ever. For example, there’s a common view that policies of the Biden administration caused the inflation. But that’s just not supported by the record of spending over the past four years. The bulk of the emergency financial aid to the US economy took place in 2020 when the Trump administration was still in control. But neither should the Trump administration be blamed with the inflation: 2020 spending programs—everything from the $2.2 trillion CARES Act to myriad other support programs passed in 2020 (an additional $1.3 trillion) were largely bi-partisan. Indeed, if the President had been a guy named Smith, it wouldn’t have made any difference: the US was going to engage in emergency spending no matter the politics, no matter the party.

To put a fine point on the question: the inflation began almost immediately after Biden came to office—just 4 months—which fits into the normal understanding of how long it takes for stimulus to propagate through the system. To be even more clear, Biden didn’t create his own pandemic relief package until mid-March 2021, in the form of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, and US unemployment was the main reason—still above 6% at the time. And again, that spending could not have been approved without Congress.

So, a non-partisan view of the two first waves of emergency relief would say that the first wave, the largest, occurred under Trump and the second under Biden—but would it really have been so different had the roles been reversed? Additionally, let’s also touch upon another bi-partisan issue: how the Fed handled interest rates. Most observers agree the FOMC held rates too low for too long given the stimulus that started flowing through the system.

On the chart below, the first two major spending bills are marked with red, vertical lines, and then the three domestic investment plans (which are incentive plans, more than they are spending plans) are marked in green.

As others have noticed, it is rather hilarious that inflation peaked in August 2022, literally the same month both the CHIPS Act and the IRA Act were passed. No, the Inflation Reduction Act did not lower inflation. Rather, the inflation was already fated to decline once the emergency stimulus worked through the system. Just like monetary policy itself, fiscal stimulus or fiscal restrictiveness are initiatives that work through the system with lags.

None, and I do mean, none of the investment programs meanwhile were inflationary, nor are they inflationary now. Inflation itself quite clearly didn’t care about those three incentive programs at the time—the IIJA, IRA, CHIPS—and still doesn’t care about them now. Incentivizing the public sector to build factories for batteries, EV, or semiconductors is not inflationary. But sending out billions in the form of stimulus checks, when supply itself is meaningfully constrained, will indeed produce inflation if you pressure the supply-demand balance hard enough. And we did.

For those who believe the return of inflation is always just around the corner, you have just been handed a real-world experiment demonstrating what doesn’t cause inflation, and what does. Most importantly, it looks like the hurdle is so high to actually create inflation, that it may take 100 year events to do so. Most clarifying of all: the gargantuan stimulus programs, monetary policy, and even collapsed supply chains were only enough to generate about 18 months of inflation. No new inflationary era began. We did not return to the 1970’s.

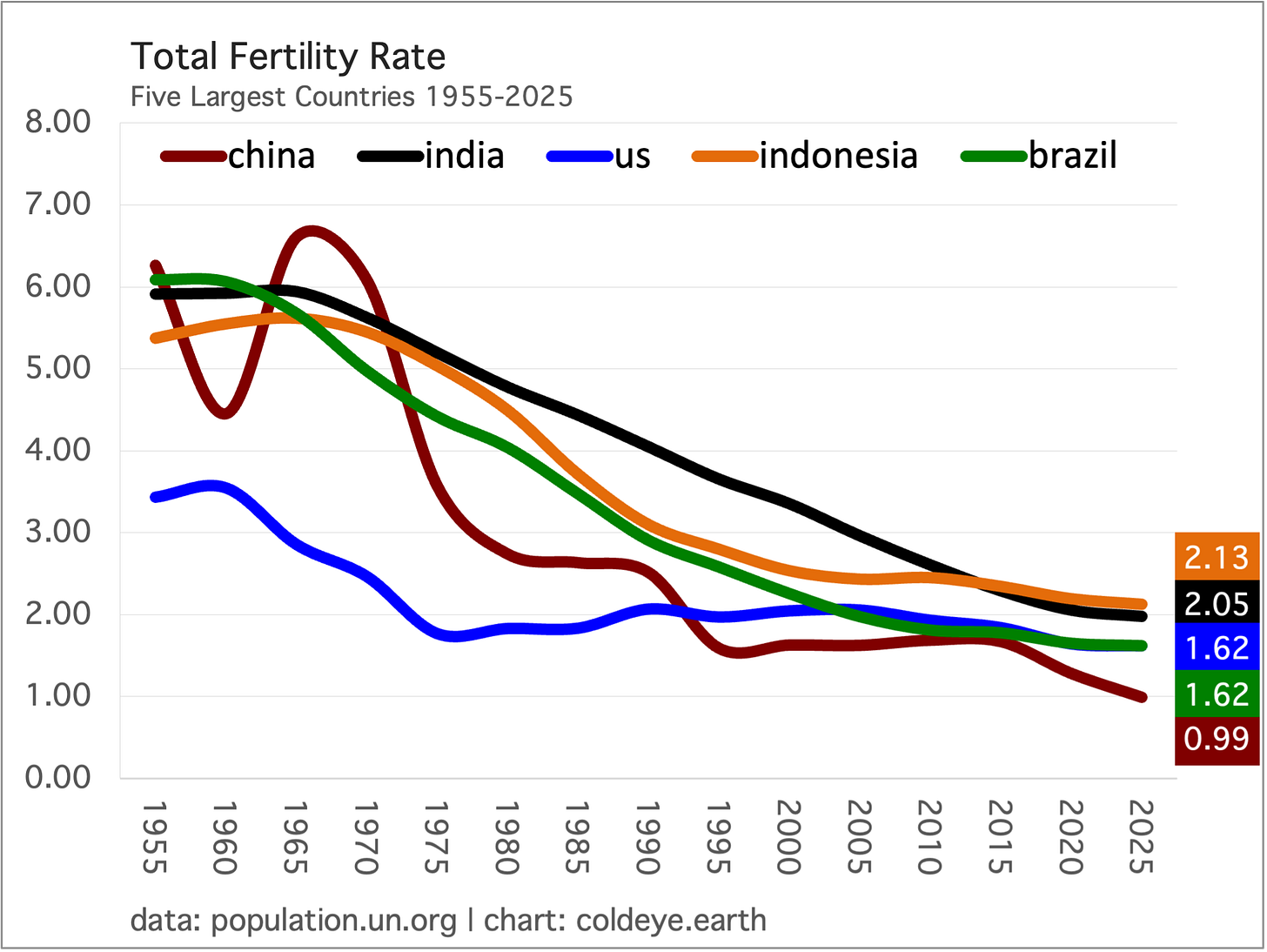

Without being too formulaic about it, it’s fair to claim global demographic trends are deflationary. No doubt many readers are aware that, in the past 30 years, fertility rates in the developing world have come down dramatically, while developed world fertility rates have sunk to lower lows. The big country sitting between these two trends is of course China: unlike India, or Africa, China’s fertility rate is not coming down from very high levels, but has rates more similar to developed world countries: already low, and going lower. Indeed, China is a major factor in the declining rate of annual net additions to population, shown in the chart below.

As recently as 2013, the world was adding a net 91.26 million people each year. But with the trend towards lower fertility rates taking hold, the past decade has seen this rate decline. While the pandemic period resulted in much lower birth rates in 2021, and 2022, this rebounded in 2023. The black histogram in the chart represents the year 2024, which begins the current UN forecast. So the world added just 70 million net new people last year. The information comes from the 2024 UN Population update.

When you look more closely, this time at the evolution of the total fertility rate (TFR) evolution over the past half century in the world’s five largest countries, it becomes easier to understand how the population growth rate can be slowing notably. Consider for example India, whose TFR was as high as 4.0 as recently as 1990, after coming down from 6.0 in the 1960’s. Today, India’s TFR matches where the US was as recently as 2005, at just 2.05. That is astounding.

Just a quick fertility review: as countries become wealthier and especially as their medical standards rise, they typically see fertility fall as prospective parents invest more of their income across a smaller number of children. This process appears to be extending across developed world economies too. The wealth created in the 20th century has been key to lowering fertility rates, despite the fact that human desires are somewhat unlimited, and that wealth also represents a claim on future consumption. Yet, at some level of wealth, acquisition of material goods tails off, and accumulation of financial assets becomes the priority. Indeed, this behavioral phenomenon has been identified as a factor in keeping interest rates rather low the past 30 years. When people are financially wealthy, they often need fixed income to balance risk in their portfolios. And this trends accelerates as populations age! So the world is aging, the world continues to get wealthier, the world is quite developed with infrastructure, and there’s a constant demand for bonds. That makes for a steep hill that inflation must climb, if it ever wants to return in a big way.

Investors need to consider the possibility that another deflationary boom is on the way. Our last deflationary boom occurred during the late 1990’s when the internet and affordable consumer computing radically altered pricing and consumption, as it removed layers of labor and other frictions, causing economies to speed up. The artificial intelligence revolution should do the same. Somewhat surprisingly, it seems many investors or observers are quite behind in their understanding of AI, believing the gains are all up ahead in the future. Yes, there will be future gains, but AI is operative right now, is being used right now. For example, I just asked ChatGPT to list some areas where AI is already operational and making productivity gains. Here are just a few points selected from a long list:

Automation of Repetitive Tasks: AI and machine learning streamline routine tasks in fields like data entry, document processing, and customer support. Robotic Process Automation (RPA) combined with AI can handle complex workflows, allowing employees to focus on higher-value activities.

Data-Driven Decision-Making: AI-enabled tools analyze massive datasets to generate actionable insights, supporting faster and more accurate decisions. For instance, AI in finance can analyze market trends in real time, while in manufacturing, it can predict maintenance needs, minimizing downtime.

Inventory and Supply Chain Optimization: AI-driven analytics forecast demand with greater accuracy, optimizing inventory levels and improving supply chain efficiency. Machine learning algorithms can detect patterns that humans may miss, helping companies avoid stockouts or overstocks.

Enhanced Recruitment and Talent Management: AI is increasingly used in HR to screen resumes, match candidates to job requirements, and analyze employee performance data. This reduces hiring time, improves the quality of hires, and enhances employee retention strategies.

Precision in Healthcare Diagnostics: In medicine, AI speeds up diagnosis by analyzing medical images, lab results, and patient records with high accuracy. This shortens time-to-diagnosis, improves patient outcomes, and reduces the administrative workload for healthcare professionals.

Coding and Software Development Assistance: AI-powered coding tools assist developers by suggesting code, automating tests, and finding bugs, greatly improving development speed and software quality. GitHub Copilot and similar tools allow programmers to complete routine tasks faster and focus on more complex coding challenges.

Energy Optimization in Smart Buildings: AI-driven systems help manage energy use in buildings by controlling lighting, heating, and cooling based on real-time occupancy and environmental conditions. This reduces waste and saves costs while maintaining a comfortable environment.

Just to add, AI is already being used by the global power sector to forecast weather (temperatures), to optimize equipment, and to ferret out savings opportunities across operations. Recently, some respected analysts have become concerned that the admittedly massive investment capex of the tech sector which seeks to enable AI capabilities will have to slow down soon until it can prove there are earnings to harvest from those investments. Cold Eye Earth disagrees! The earnings from AI investments are already flowing! We will not only hear from companies like Microsoft that they are boosting revenues from their enterprise offerings, but other companies in the industrial sector will eventually report savings they too are gaining from AI integration. US productivity growth, by the way, keeps chugging along.

The US bond market would be much happier with a Harris Presidency, given the inflationary tariff and spending plans proposed by Trump. Admittedly, analysis breaks down a bit in the face of Trump economic proposals because it’s historically unclear how seriously to interpret campaign trail promises vs. actual policy outcomes. Most economists have rated the two different paths declared by each candidate and universally concluded Trump’s plans expand the deficit further, while also lifting the cost of consumer goods.

One of the reasons the Harris plans score better on both spending and inflation surely has to be that, without any action taken by Congress, the 2017 tax cuts will revert back automatically if not renewed. That means both corporate taxes and rates on high-income households would obviously increase revenue. Moreover, it’s highly likely Democrats will lose the Senate, creating gridlock. And gridlock has historically been friendly to markets because more often than not it restrains spending plans.

To put this in context, let’s check in with a different chart of economic data that pairs well with the inflation discussion in the first essay of today’s letter: government expenditures. Notice how the two big spikes in government spending largely occur before Biden gets to office. But this is not a political interpretation. Cold Eye Earth has already argued that the spending on the pandemic was for the most part bi-partisan (as it was elsewhere in the world too). Rather, the point here is that these spikes in expenditures are so unusually large they simply can’t be repeated.

Expenditures are now rising gradually, to be sure. But the bond market has pretty easy math if Harris wins with gridlock: all the big fiscal spending moves further into the rearview mirror, and factors in the US growth picture come to rest on the existing incentive programs (IIJA, IRA, CHIPS) and the condition of the global economy.

To wrap up, the following three assertions could not be more clear:

If you want to ignite inflation in the developed world you will need a very big bazooka, the size of which is rarely seen or deployed.

The deflationary supertrend is so well established that fighting it gets you one maybe two years of respite, before the trend reasserts itself.

The lingering suspicion that inflation will return is everywhere and at all times a reflection of human psychology: the hangover of fear that reliably follows a bad experience. This masks the fact that no rational argument for inflation’s return exists, at this time.

Power generation from combined wind and solar has now surpassed coal in the US. Coal’s crash and wind+solar’s ascent has helped remove inefficiency from the power system, as the high operational expenses associated with running coal are successively expunged. To capitalize on that difference however, the US will need to deploy alot more storage, which will ensure that all the green electrons are utilized.

The fossil fuel underlayer continues to grow, highlighting the fact that, even when we halt its growth, time will still be required to force it into decline. There is no question the rate of fossil fuel demand growth has slowed meaningfully. In the chart below, for example, 2019’s consumption was only barely above 2018; 2021 matched the 2019 level; and the growth from 2022 to 2023 was just 1.4%. Global oil consumption is not yet ready to fall. Global coal consumption won’t grow either, but is also stubborn about falling. And finally, natural gas continues to grow—strongly. The underlayer is far stronger than most have assumed.

—Gregor Macdonald