Green Growth

Monday 29 June 2020

The just released BP Statistical Review showed combined wind and solar are crowding out growth from all other energy sources in global electricity. The data further confirms the ongoing storyline from the microeconomic level: utilities are accelerating plans to shutter existing fossil fuel capacity (coal, especially) and signing up to cheaper, better, faster energy technologies. Global coal consumption meanwhile, which peaked in 2013, appears finally ready to enter permanent decline. While metallurgical coal will likely enjoy a long tail of demand, it’s just not enough to support the market. The signal coming from the thermal coal market meanwhile is pretty clear: coal, in power generation, fell 2.65% last year. There’s just no way out, for coal.

Measuring the ability of combined wind and solar to cover the annual marginal increase in global electricity demand is an effective way to measure not only their own progress, but decarbonization more generally. In the chart below, you can see the twin sources have been “testing the fence” if you will for a number of years. Always showing promise, but never quite dominating the scene. Indeed, in 2018, when global air conditioning demand surged along with global economic growth, growth of sources ex wind+solar surged to meet overflowing demand. Last year, however, when total demand rose by 352 TWh, combined wind and solar finally crested over 300 TWh. Given the slowdown forecasted for this year and next in overall economic growth, we are likely to see wind and solar dominate more consistently this decade.

The IMF in June downgraded their 2020 global GDP forecast considerably, compared to their previous April outlook. Now that we are halfway through the year, however, there’s not much drama in the change from -3.0% to -4.9% growth. Rather, it’s the IMF’s fuller digestion of the crisis, and its portrait of a far slower recovery, where attention should focus. Compared to the pre-crisis GDP forecast, for example, next year’s GDP is now on course to be lower by “some 6 and a half percentage points,” to quote the full report. This represents a massive loss of global output. But remember, always watch your rates and levels. The IMF forecasts a rebound next year, with global growth advancing 5.4%—but from a very depressed baseline.

One of the best ways to visually disentangle dramatic declines in growth, from strong rebounds that tend to follow, is to lay out the losses expressed as an area. And the IMF does just that their blog post, The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression:

Output losses are a helpful way to think more deeply about the long lasting damage to economies, and individuals, as crises profoundly interrupt progress. They are precisely the reason why wage growth, job opportunities, and pricing power can take much longer than anticipated to return. Let’s also remember the sustained pressure that pandemics have historically brought to bear on societies—a central focus of The Gregor Letter over the past three months. And even after pandemics resolve, in their wake, deflation has typically shown up not for a short while but as a long-term echo.

The Gregor Letter base case for economic recovery remains unchanged, as the global economy will likely face a three year struggle, with more sustainable hope appearing in 2022. Needless to say, the extraordinary policy failure in the US continues to be a major contributor to this outlook. In previous letters, over the past months, I have gone into great detail in the base case update. Now, as the next wave arrives, I will let the unfolding tragedy speak for itself.

Polling for the incumbent US President continues to collapse. The numbers are so bad that chatter is rising, in Republican circles, that Trump should consider resigning. Last week, the much anticipated high quality polling from New York Times/Sienna showed three main themes: Biden is trouncing Trump on the national level; Trump is also now far behind in the battleground states; and incredibly, Trump is now seeing his support erode among white voters, and even white voters without a college degree. How much movement or strength lies behind the distressed chatter in Republican circles is, for now, unknown. But there’s a simple rationale to the prospect that Trump bows out before the election. By doing so, it might remove some of the tail-risk that threatens to wipe out Senate Republicans running for reelection. Or, at least that’s the idea. In a recent televised interview, veteran campaign manager James Carville said “there is now a greater chance Trump resigns, than he wins the election.”

The Robert E. Lee Monument statue in Richmond, Virginia has been transformed into a powerful projection screen. The nighttime displays have featured images of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman appearing on the monument’s base, as Lee’s horse rides in silhouette, stamped with the letters BLM. This cinematic act is, without question, an artistic masterstroke. Hence:

Global oil demand growth has likely peaked. That’s the central conclusion of the coming update to Oil Fall, which will now arrive in late July. There is however no evidence that the pandemic and its associated crisis—which certainly brought the peak forward from the 2021-2022 period—will equally accelerate the transition away from oil. While that may very well happen, the lower risk forecast is to declare the plateau of global oil growth has now begun, and the oil industry is now very much a no growth industry, with nothing but stagnation ahead. We could fluctuate on this plateau for several years. Here, it’s useful to consider how the entire global coal industry crashed and went bankrupt earlier last decade (when coal peaked in 2013), and yet consumption oscillated for some years to come. I have warned several times that an overfocus on Western oil companies as the proxy for oil dependency is a mistake. Corporate bankruptcy does not prevent the extraction of coal, or natural gas, or oil. All that said, we will surely mark 2020 as the beginning of the end for oil.

Just to remind: subscription prices for The Gregor Letter move up from $50.00 to $75.00 per year, and $5.00 to $7.50 per month, this coming Wednesday, 1 July.

The door has kindly been held open for three months to enable all readers to lock in at the lower $50 level. The price change will take place later Wednesday evening.

Green growth on a national or global scale remains hard to quantify, but the data post 2010 strongly points in that direction. The third chapter in Oil Fall lays out in some detail the waste associated with combustion, and all the extraction, shipping, materials, and costs which make that system less economic than the one offered by renewables. It’s simply axiomatic that wind and solar’s mind-blowing cost savings compared to coal and natural gas derive very much from a much less intensive call on resources. And in particular, that wind and solar are energy capturing devices running at very low cost, once erected.

Andrew McAfee, professor and author at MIT, has been pursuing this storyline and you can review his claims both in a recent podcast with Sam Harris, and his recent book, More from Less. McAfee’s thesis, which I generally regard as being on the right track, is that global growth has been becoming less resource intensive. Already, however, you can see the myriad ways in which such a claim could attract disagreement. For example, many processes and products which now form GDP are very much digital or intellectual in nature. Those products and services have every right to be included in GDP—and it’s not that dematerialization created them, but rather, they are themselves simply not material by design. So this component of modern GDP, as the numerator, can very much continue to expand with little pressure, and thus little movement in the denominator: raw materials. Moreover, population continues to grow. So, there are myriad opportunities to confuse or conflate absolute with marginal growth in resource consumption as we head above 7 billion people on the planet. Still, as an energy historian myself, and using energy as a proxy, I think McAfee is on the right track—though, I would conjecture his thesis will become more true, more clarified, in the years ahead than it is right now.

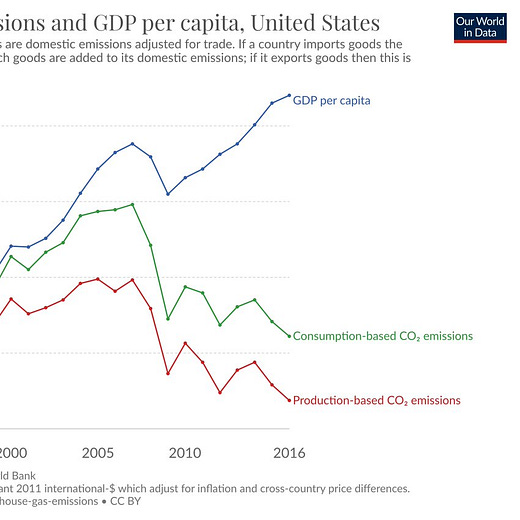

Jason Hickel has recently offered a strong retort to McAfee’s thesis, in an essay published this month in Foreign Policy. As you read through Hickel’s piece, you will notice a familiar and evolving accounting challenge: how to quantify material consumption for a country like the United States in an era of soaring product imports. Moreover, even a layman knows that the material intensity of manufacturing, especially in the highly unregulated centers of Asia, and China in particular, is high. After all, Coal 2.0—the dramatic resurrection of the 19th century energy source—was almost entirely a China phenomenon, all in service of production consumed by the West. And it would be an understatement to say this multi-decade trend was grossly inefficient. If anything, one would expect data to show materialization to have intensified between, say, 1990 and 2010.

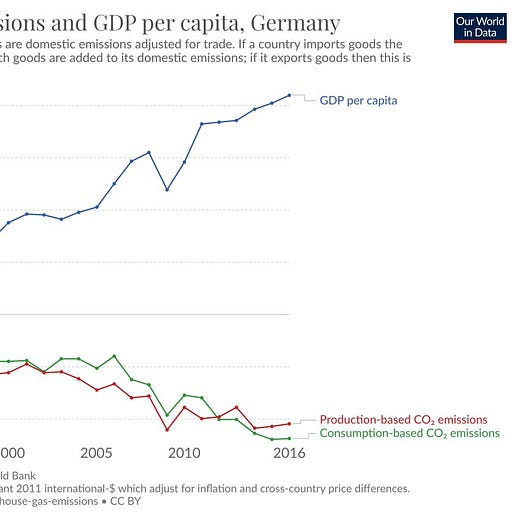

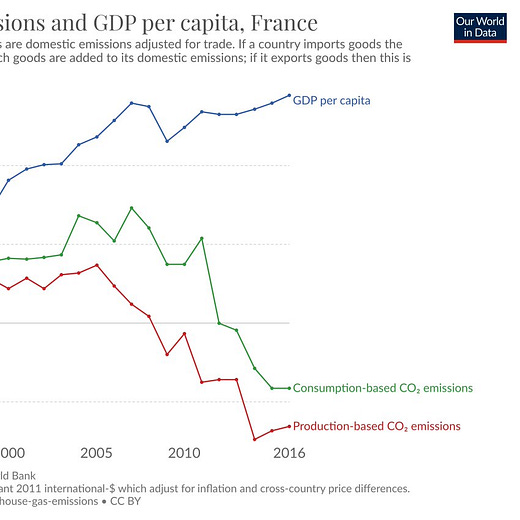

Rather than trying to adjudicate Hickel’s and McAfee’s views—because I additionally want to avoid setting up an either/or proposition here as well—I would like to make a few general points, while encouraging readers to explore the claims for themselves. First, I think it’s going to be more difficult to settle disagreements of this kind, or more importantly come to a consensus on this question, using 20th century data. All the action is taking place now. So if dematerialization is your game, you probably want to concentrate on data series in the 21st century. Second, one is going to have to become more familiar with the economic literature, in how resource consumption accounting takes place. For example, import-adjusted emissions—indeed, GDP growth with either flat or declining emissions—seems like a pretty good marker to me. To wit:

Finally, I think it bears repeating that society can (and will) come up with any measure of GDP it so chooses. Implications: the numerator in the GDP-to-resources ratio is partly social. GDP will change, the composition of GDP will change, and different societies will account for GDP differently. Many observers really dislike GDP as a measure overall, and with good reason. My take: keep revising, making GDP better.

One mistake that everyone should avoid, however, is cherry picking timeframes. Be honest. For example, given that the largest woosh! in the global buildout of wind and solar doesn’t truly begin until after 2010, don’t write an essay making the claim that ‘wind and solar have contributed little to decarbonization since the start of the new century.’ I call this drowning the signal.

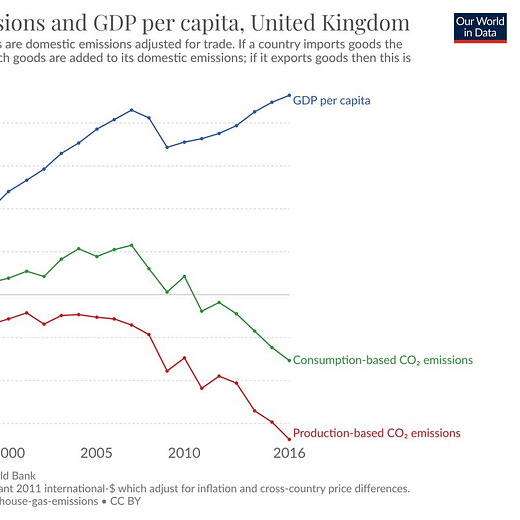

The final chart in the set of Max Roser examples (up above) is instructive because the UK very much embodies the accounting challenges for a modern economy that 1. outputs large volumes of intellectual products, 2. imports large volumes of products manufactured abroad, and 3. has done an extraordinary job converting its electricity to wind and solar, while also using a lot less oil. Emissions are an excellent unit of account and it’s simply inarguable that the UK is growing GDP, in this case, as trade-adjusted emissions fall.

Notice also in the UK chart how the great recession caused a more visible interruption in the previous trend. And then afterward, how the buildout of wind and solar, with its cost declines and lighter call on materials, really kicks in starting last decade. And here we are. The UK, which I have called Another California, is a very good model for the good things to come in OECD countries. If you’re hunting for green growth, your time period has arrived.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

Photos: 1. Southern view of Mt Adams from Trout Lake, Washington, June 2020, Gregor Macdonald. 2. Southbank, London, March 2020, Gregor Macdonald.

Correction: The original entry concerning the Robert E. Lee statue has been updated to reflect that this is the Lee Monument located in Richmond, Virginia—not the Lee Monument located in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.