Hopes for China

Monday 1 September 2025

China’s industrial revolution has largely been defined by the relentless growth of its electricity generation over the past three decades, as the nation transformed itself into the world’s workshop. The recent tendency to declare that China is now becoming an electrostate is a bit odd in this context, because the term is either too slippery to have reliable meaning, or succumbs to newcomer bias: when was China ever not an electrostate? Unlike the U.S., China did not grow its economy on the back of oil. Indeed, it wasn’t until this century that Chinese incomes were large enough and growing sufficiently to start adding domestic consumer demand for petroleum. China had to go through a build up of its cities first, as poor workers poured in from the countryside to take part in the manufacturing boom (Lewis turning point). The U.S. by contrast entered the era of consumer consumption much earlier, immediately after WW II, kicking off the long ascent of its lifestyle and consumer driven demand for gasoline.

In my 2018 series Oil Fall, my chapter on China addressed the divergence between the two countries:

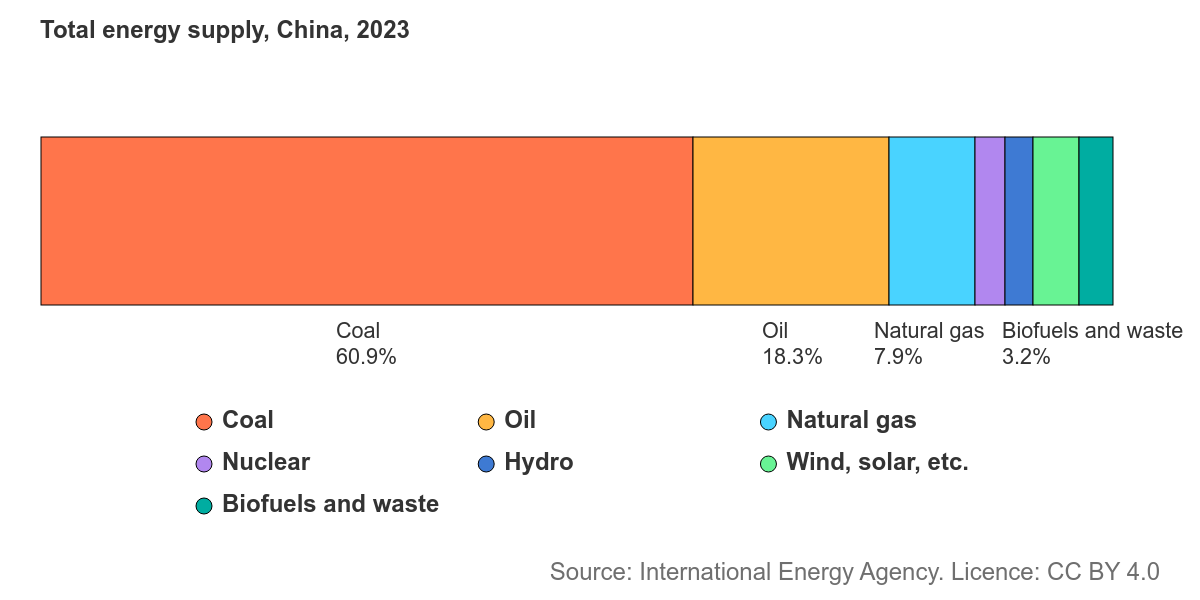

It’s also important to understand that China is a nation that runs primarily on electricity. China is not an oil nation. It’s a power nation, a testament to its strong manufacturing identity. In 2017, China consumed 3132 Mtoe of energy from all sources, but only 608 Mtoe of that total was provided by oil. Oil provides just under 20% of China’s total energy demand. Compare this to the United States, whose total consumption of energy from all sources in 2017 was 2235 Mtoe, of which oil provided 913 Mtoe. The United States, by contrast, is still very much an oil nation, where oil provides nearly 41% of its energy.

Indeed, one of the reasons China has had such an easy time integrating fast growing wind and solar power—without the bottlenecks that appear in other domains—is that unlike the U.S. it has been working on expansion of its powergrid for many decades, primarily led by coal. If we use the starting point of 1990, which most researchers identify as the start of its modern industrial revolution, the data shows that China’s growth of electricity generation grew an astounding 1500%, from 621 TWh in 1990 to 10087 TWh last year. For context, China started 1990 generating less power than Japan (882 TWh) and wound up over 30 years later generating 10X the power of Japan (1016 TWh). This is not the record of a nation just now emerging as an electrostate.

Here is a nice graphic through 2023, showing the composition of China’s total energy use. While there’s certainly alot of metallurgical coal used in China for steelmaking, you can pretty much read the coal category in the chart below from the IEA as a decent proxy for electricity.

Clearly one of the intents behind this new-ish jargon is to paint a contrast between China, which has developed on the back of coal, and the U.S., which not only remains far more car-dependent, but has become a giant of oil production and petroleum refining, or, as they say, a petrostate. As long as we avoid the error of thinking the divergence between the two countries is recent, that’s fair. But even here, there are recent trends that bear watching.

• What do we say about the fact that U.S. oil consumption peaked twenty years ago? And relatedly, that U.S. electricity generation has broken out of a two decade flatline around 4000 TWh and is heading towards 4500 TWh, rapidly. What bars the U.S. from becoming, eventually, an electrostate?

• Although China’s oil demand grew by far less over the past three decades, a 600% increase, its oil demand growth in the last decade has picked up the pace. To be sure, this growth is now running into a wall formed by the titanic adoption of EV cars, buses, and trucks in China: oil growth will eventually be halted. That said, China’s oil demand now sits barely 10% below U.S. levels. So, electrostate is a rather grandiose term for the second largest oil consumer in the world.

Cold Eye Earth has an allergy to geo-political concepts. Terms like petrostate inevitably function as a kind of Christmas tree that can be decorated with every unfalsifiable concept imaginable, and these themes inevitably spill into other suspicions around the dollar, the petrodollar, spheres of influence and so forth. To be honest, events and developments in recent world history seem more often to be breaking out of long-held patterns, than adhering to them. In such a world, the value of labels can crumble quickly.

Since 2005 when OECD demand peaked the oil industry has had to entirely rely on the Non-OECD for growth, which of course is mostly driven by China. So we’ve all been quite aware during this time that once China’s oil demand peaks, global oil demand will peak. Based on recent trends, and especially China’s historic growth of electrified transport, we are closer than ever before to a peak—but with a couple of cautionary notes.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cold Eye Earth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.