Impressive Arrays

Monday 23 August 2021

The robust effectiveness of solar power continues to baffle observers who’ve still not absorbed the technology’s unique edge. Neither dense nor powerful, solar technology captures diffuse energy and cuts against a multi-century march towards singular, sometimes monolithic human solutions. Walls, guns, dams, battleships, powerplants, rockets, nuclear fission, and of course our old friend oil, are examples of how society has increasingly discovered (correctly, in many cases) that bigger is indeed often better. The key to solar’s success however runs in the opposite direction. Each individual unit of solar is small, tiny even, and decidedly unpowerful. Solar’s edge comes instead through mounting these micro-units into large arrays. And in such arrays we see solar’s intrinsic advantage: this is manufactured energy, and therefore adheres to the falling-cost phenomenon that steadily rolls out with duplication. A massive, 2 GW solar farm is therefore the sum of many small, individually weak parts stitched together to form a far more powerful machine. Does this matter?

Because the landscape of new energy is likely to branch along such contours, yes, it’s worth pondering how arrayed solutions, rather than singular solutions, will be increasingly more common. Consider aerospace, where advances during the 20th century mostly charted a course toward jumbo-ism, culminating in the 747, the A380, and military cargo planes, like the C-130. Because the optimal ratio between weight and battery size will be harder to fashion at a similar scale, electric solutions in flight will probably guide towards much smaller craft. And that’s fine, from a cost standpoint, because fuel costs for battery-powered flights will very obviously be cheaper. Hence, we are likely to see larger fleets, composed of smaller craft, flying shorter distances but more frequently. DHL for example has now ordered electric cargo planes to be constructed by Eviation, of Seattle. And, we are seeing an explosion of start-ups and innovation in small-craft flight more generally.

Two-wheeled transport is another area where micro devices have stormed the market, with alot more to come. While e-bikes, e-scooters, and China’s sub-compact EV market have gained most of the attention so far, it’s worth casting a glance to one of the largest two-wheeler markets in the world, in India. Traditionally petrol-powered, new incentives and looming emissions regulations are going to start pushing this fleet towards electrification. I just reported on these developments for Transition Economist, and the implications are significant. India’s two-wheeler fleet collectively far outpaces all other sectors in terms of oil demand; so a transition to electric (E2W) will not only suppress oil demand growth, but will perfect and accelerate electrification more generally in the country. Simply put: infrastructure built for the sake of micro-mobility will function and be interoperable with both the supply and demand side of clean energy.

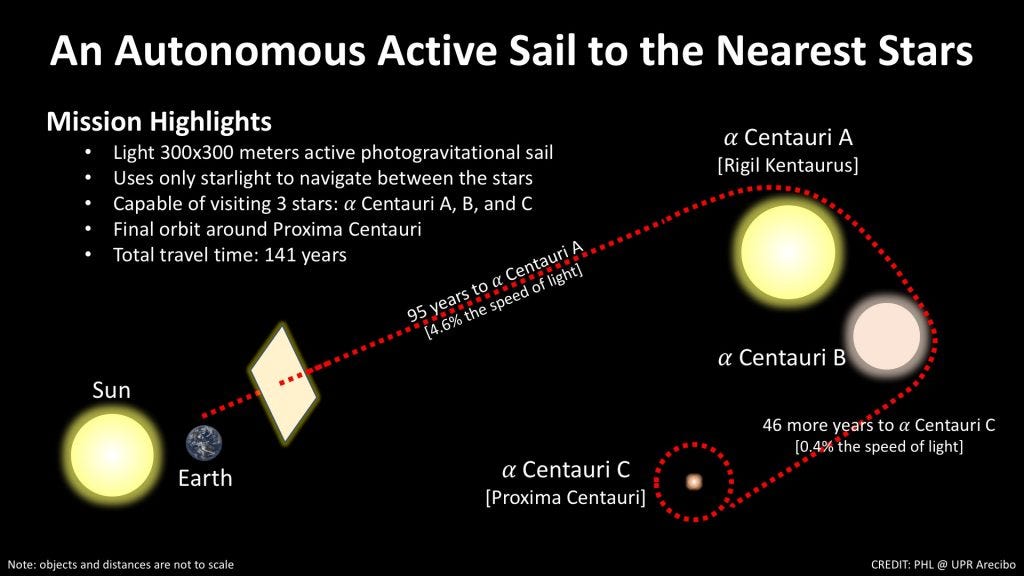

For a more theoretical example, one that’s rather ethereal but may be useful, is the starshot/lightsail project revealed a few years ago, with the backing of Stephen Hawking. Using a fleet of small, solar-powered “sail craft” rather than a singular vessel with onboard propulsion, the projects aims to re-think interstellar travel. Here we see a number of current, earthly themes coming into play: the craft would be unmanned, drone-like, and would leverage small-scale dynamics. Each ship would be defined mostly by its total sail area, around 4 X 4 meters. And many of these would need to be deployed to account for the decay and loss of some portion of the original fleet. Note again: the strength in numbers strategy.

The concept of decentralized energy is now fairly well understood in energy circles, but is perhaps less accepted more widely. Mostly, the proposition of new energy is about networks and interconnectivity, which will mostly happen through an increased pairing of storage (batteries) alongside the deployment of wind and solar. Yes, a great deal of global wind and solar generation will be arranged into massive arrays. But a good portion will be very small scale, and storage for homes and commercial properties will proliferate. Indeed, as the cost of batteries continues to fall, most new homes and businesses will be constructed with some moderate storage capability. There is no shortage of devices that can’t be marshaled to the network. That includes everything from the obvious, like using an electric Ford F-150 as a backup battery for one’s house, to attaching radio devices to water heaters, linking them into a networked, virtual battery.

The useful theme to understand here is not that the age of big things is over. The US military will continue to field something like the C5 Super Galaxy, to be sure, but that unusually large transport plane will always have to be powered by jet fuel. Rather, that scale and proportion are exceedingly compelling variables, and we seem to be entering an age where we are fruitfully exploring the other end of the spectrum, and finding (once again?) that small is beautiful.

The US goes to war far more easily than it raises the required capital to invest in itself. That’s the depressing conclusion from Adam Tooze this week, in a lookback essay, How We Paid for the War on Terror. Worse, while most seem to agree the sums wasted over the past two decades could have been put to use addressing massive US infrastructure deficits, the culture appears unable to escape this conundrum. Tooze lays down a rather devastating epitaph on the whole affair:

The tragedy is not that the War on Terror crowded out better projects. The tragedy is that the better projects were never on the agenda of power at all. The tragedy is that the one thing that those with power and influence could agree on was war-fighting. In a profoundly divided polity, with deep divisions extending into the elite itself, national security is the one area where a degree of bipartisan agreement was still possible.

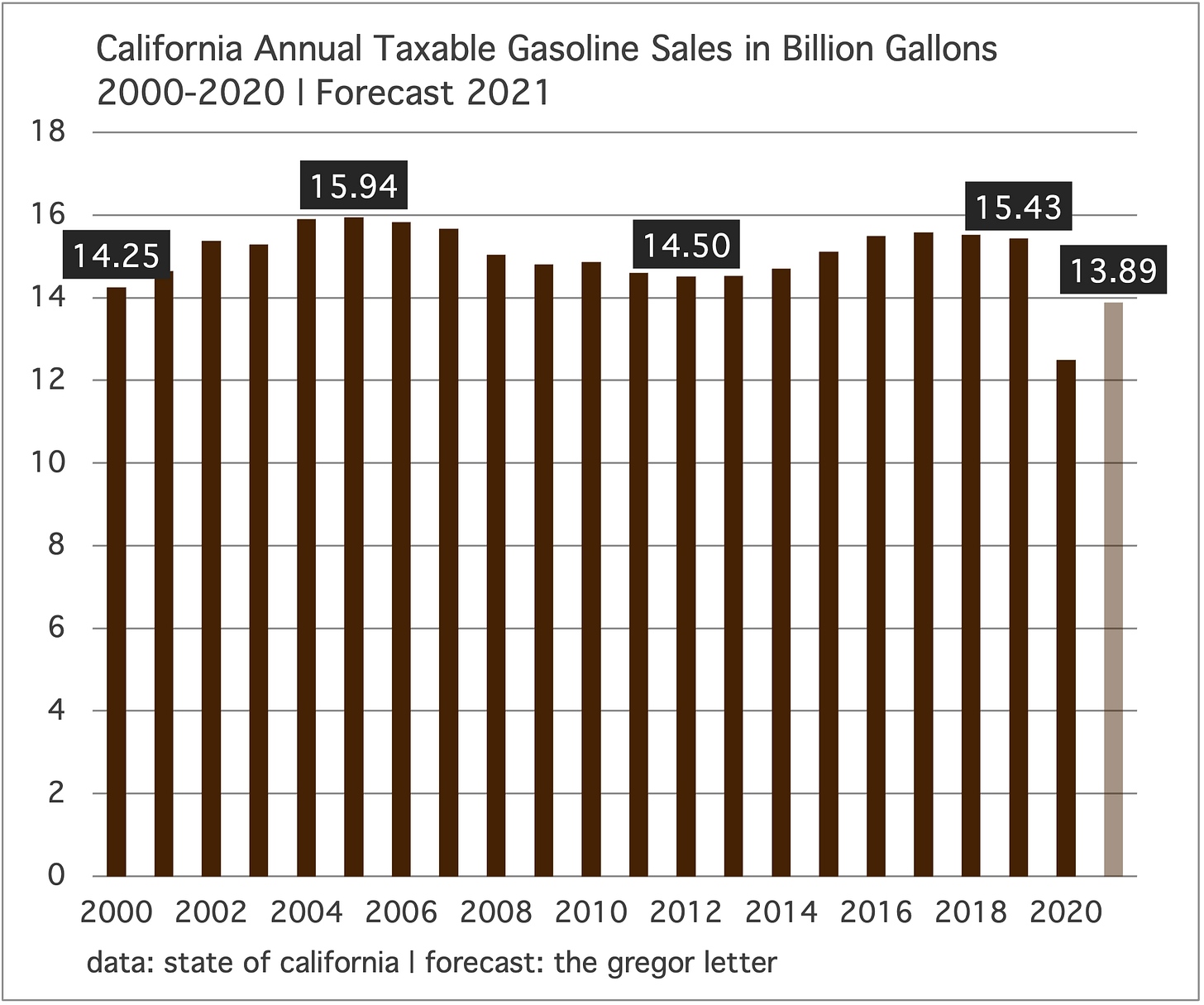

California gasoline consumption is recovering, but may struggle to reach previous highs. The Golden State remains our best proxy, in the US at least, for the approaching confluence of EV adoption, oil consumption disincentives, and the electrification of transport. California has mostly halted gasoline demand growth for over a decade, for example. But the state is also a lens through which to absorb how challenging it will be to force gasoline consumption into decline. That car dependency is so thoroughly embedded in California is useful also, in this regard, as it provides a hard case for the extreme political difficulty of dislodging personal vehicles from our cities.

However, as discussed in Last Dance for Oil, it may be the pandemic that does some of the work our policy complex has failed to do. Through the first four months of this year, California gasoline consumption remains down about 13% compared to 2019 (the pandemic year 2020 is of course not useful for comparison, in this regard). It would be reasonable to expect further recovery, but it looks like consumption may still wind up down around 10% compared to the last “normal” year. Why might that be? The conversion of temporary work-from-home changes in commuting to a more permanent state of workplace flexibility. Return dates have been postponed once again, and California is probably the leading edge of coming changes in how we use, or don’t use, office space.

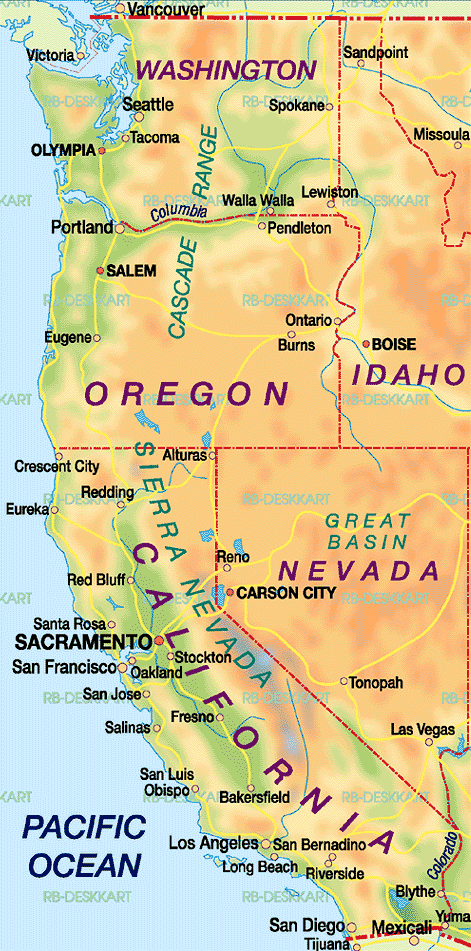

Oregon Governor Kate Brown threw her support behind the controversial Interstate 5 widening project, in central Portland. While the compromise will extract legitimate development gifts to the surrounding surface streets (improved bike lanes, better street design, and most important—the moving of the Harriet Tubman primary school) the widening will accomplish none of the congestion goals put forward by the Oregon DOT. And it’s ironic that the political culture once again has avoided road charges or congestion charges, as these could be put in place far more quickly, to greater effect. The construction project itself will add years of extra drive-time to the route.

But Brown’s inability to fight the car puts in relief a rather discomfiting reality that many climate activists would prefer not to know: it’s not Exxon Mobil and the rest of “big oil” driving these decisions. It’s Democratic governors and mayors in deep blue states and deep blue cities who fear a far more powerful constituency: car owners, most of whom are their own voters.

From Seattle to San Diego we have been showered with climate white papers, speeches, earnest declarations, and aspirational targets telling us how mayors and governors with the support of the people will fight climate change. Ah yes…as long as that fight doesn’t tamper with personal car ownership. We even have loud admissions, from California Governor Newsom, admitting that the transportation sector is now the top source of US emissions across the nation—and, especially in California. But again, very little direct action is being taken against the existing fleet of automobiles.

At any time the mayors and governors of the three big West Coast states can ask the US Department of Transportation to start the process on congestion charges in their major cities. That is the only way to tackle the call on gasoline that the existing ICE fleet will generate for many years to come. EV adoption alone doesn’t solve this. But by failing to undertake such policies, the West Coast governors are perhaps doing climate activists a favor. A popular theory of change has long held that “big oil” is pulling all the strings, and that to fight back against their policy influence one must install climate friendly politicians. Well, here we are. So if this has been your theory of change, you need to move on now to a better theory.

The ways in which we’ll use hydrogen can be complex and time consuming to understand. But Michael Liebreich, the founder of New Energy Finance (now owned by Bloomberg) has been generously sharing his insights, and once again has published a long thread at twitter. Michael’s aim is to aid understanding by creating a ladder of use cases that run from the easy or inevitable to the very hard, or uneconomic. Highly recommended:

The learning rate is alive in well in onshore wind. And by the time the US starts deploying offshore wind, from Massachusetts to Virginia, the same phenomenon will unfold. According to the EIA, the cost of onshore wind has declined by 27% since 2013. But note how those cost declines started to accelerate anew after 2017.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.