Last Dance for Oil

Monday 26 July 2021

Last year’s dramatic decline in oil demand reveals where structural weakness and strength now reside in the global market. We’ve known for a decade of course that oil demand growth has steadily migrated from the OECD to the Non-OECD. Indeed, since 2010, 100% of global demand growth has unfolded outside the OECD. Oil producers lost the OECD many years ago as a demand growth center. But the pandemic year, while an outlier in many data series, tells us a great deal about the current fault-lines in demand. In short, OECD oil dependency is far weaker than understood. And rather fearsomely, China oil dependency is far more robust.

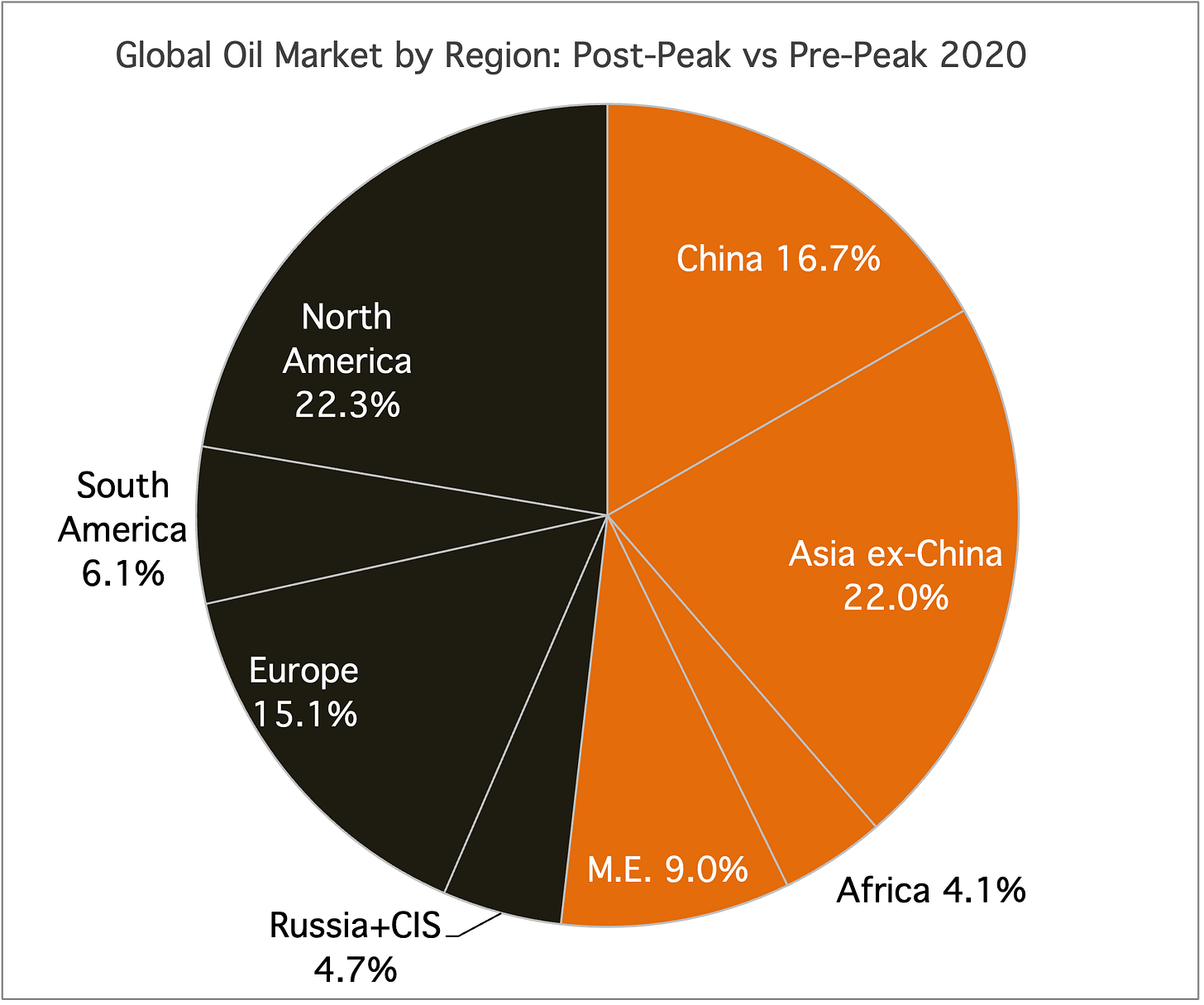

First, let’s take a look at demand by regional market share in 2019, when the world was humming along as normal. An earlier version of the chart below first appeared in Oil Fall, with the central observation that about half the market had already seen peak demand, with the other half still building. This remained the case in 2019, with the OECD along with Russia and South America well entrenched in post-peak, no-growth mode, as Asia and Africa, led by China, carried onward.

To accompany the market share figures above, the OECD consumed 2079.6 million tonnes of oil in 2010, and 2065.4 million tonnes in 2019. An almost perfectly flat demand performance. Indeed, the OECD peaked in 2005. But the OECD’s flat performance this recent decade illustrates a separate challenge: the peaking of fossil fuel demand growth without any concurrent decline, or what I call the plateau problem.

In the pandemic year however we see that OECD demand strength is far less structural, and has high sensitivity to macroeconomic conditions: commuting in particular. Both Europe and North America saw demand fall by a whopping 13%, as China’s demand actually rose by 2.27%. This shifted the plate tectonics of global demand (admittedly for just one year), pushing post-peak regions to less than half the market last year.

While South America probably contains minor potential for further oil demand growth among post-peak regions, it is far likelier that economic development there will leapfrog petrol-based transport, and begin to branch towards electrification. Conversely, existing petrol driven two-wheeled transport across Asia represents a sturdy form of structural demand dependency and China more broadly, along with Africa, remains latent with further upside oil demand potential.

That sales of ICE vehicles peaked in China four years ago is not enough to trigger outright oil demand declines in China. This is the same problem seen elsewhere, across the OECD. But it is also the case that oil, as a product, has now lost its grip on growth more generally. What does it say that such a large portion of demand was so quickly knocked offline in the OECD in the pandemic year? It suggests that without commuting and frankly a large number of short-distance, discretionary trips, oil demand in the OECD would be significantly lower.

The oil market is enjoying therefore a rather classic, one-time rebound from the deep-hole lows of last year. This injects cash into the western oil and gas sector, but not enough cash to encourage a fresh round of investment and exploration. Oil believers are certain this lack of investment is a mistake, and that the next units of global GDP will absolutely require new units of oil supply. But there is no longer much of a linkage between the two. OECD GDP has grown nicely for a decade with precisely zero new barrels of oil required. This is particularly true of the United States, where oil demand peaked in 2005. This small but enduring fact continues to surprise people.

Oil’s position now in the world economy is like that of every other incumbent technology or service that stops growing in the face of newcomers, but, persists on the back of path dependency. The western oil industry is right to not invest much in new supply, and critics of this practice are wrong. The pie of global demand has stopped growing, and over the longer term the only profitable oil to be drilled will increasingly come from the ultra-low cost producers in the Middle East. They will enjoy utility-like revenues for many years from oil as the western firms decline, consolidate, and go under.

Long-term changes in commuting and workplace schedules provide the ingredients required to finally kick-off sustained declines in global oil demand. Either-or-ism remains the bane of all good analysis, and the current conversation about workplace and commuting changes certainly falls into that trap. The vast majority of global workers will have to return to the workplace. But, a large tranche of workers will not. And therein lies all the difference. Don’t fall into the trap of picking one, over the other.

Q1 2021 California gasoline consumption for example, at 3.108 billion gallons, was 15.3% below Q1 2020 demand at 3.669 billion gallons. Is that a fair comparison, given that emergence from the pandemic didn’t really get going until Q2 2021? Not only is it fair, it’s quite instructive. Q2 2020 gasoline demand in California, the deepest quarter of declines across many indicators, was pounded down to a deep low of 2.666 billion gallons, a fall of 31% over Q2 of 2019, at 3.854 million gallons. So even as California gasoline demand started to rebound sharply by Q1 of this year, demand, while higher than the lows, remained meaningfully below the highs. And California is set up now to be the epicenter of workplace changes, with many fleeing the state to live in the Mountain West and those who are staying poised to switch to part-time office schedules.

Many remain dismissive of the post-pandemic thesis of permanent commuting and workplace changes. Soon, they will have to climb down from that view. More than half of global workers polled by LinkedIn want a hybrid work-home arrangement. Remote-work job postings are soaring, and these postings receive far more responses in accordance with those same changing preferences. We cannot put the toothpaste back in the tube, as they say, and the revelations that burst forth during the pandemic are here to stay.

You will have also noticed that cities from Providence to New York to Portland to Los Angeles are also getting strong feedback about making street closures permanent, and making outdoor dining permanent, as the trend to formalize these pandemic practices takes hold. Separated street barriers and other accoutrement to foster and protect the burst of urban cycling is also moving forward rather swiftly. The Brooklyn Bridge just added hard-separators for a bike lane. Commuting to New York City itself does not look like it will ever recover fully, and that is likely to permanently affect Midtown real estate. Of course, NYC commuting patterns don’t really impact oil demand given rail transit density—but they’re a proxy for changes to take place in car-based cities as well.

And what about on the national level? The story here is similar to California’s. US petroleum product consumption through the first 5 month of 2021 reached 18.778 mbpd. Unsurprisingly, that’s a big recovery from the first 5 months of 2020, when product consumption fell to just 17.757 mbpd. But the similar period in 2019 saw 20.361 mbpd of demand. Frankly, getting back to those 2019 highs suddenly seems quite hard. Especially as EV sales in the US are finally ready to start moving up from a low base.

For ten years now, the OECD has offered zero growth to global oil producers, but the OECD was not exactly useless in this regard: by failing to decline, the OECD stood as a pillar of dependency. Now, however, it is no longer clear that the growth in the Non-OECD can escape the drag. OECD oil consumption looks like it has started its more pronounced decline. The IEA noted for example, as early as March of this year, that global road fuel demand has now peaked. Yet another warning.

The front-page-news recovery in oil prices, and oil and gas shares and associated ETFs, has temporarily stolen attention away from the multi-year struggle that was already taking place in the oil sector prior to the pandemic. As the re-opening carries onward, we are about to have a new epiphany: global oil consumption may eventually crest very briefly around the old highs of 2019, but will not be able to live for long at that level.

Electric vehicles sales are starting to really take off, with China and Europe emerging as the main growth centers. Volkswagen’s EV sales soared 165% in the first half of 2021 and EV sales were pretty good in Europe last year: so no, this was not just a base effect producing unusual YOY growth. European EV adoption is now quite serious. Ernst and Younghas moved up its global EV adoption model by five years, and now expects that by 2028 ,European EV sales will surpass ICE sales. China meanwhile, as readers know, essentially produced the peak in global ICE sales around 2017, and now EV sales in the country have crossed well above the crucial 5% market share take-off point. Over 1.1 million EV (NEV) were registered in the 1H of 2021, putting the market on pace to over 2 million units for the year. The US remains the laggard and notable outlier. But that is about to change.

The IEA now forecasts that global petroleum product demand next year will come very close to the 2019 highs. Well, that’s probably true. Momentum in the global economy, coming up from the crater of 2019, could very much sweep oil demand from a robust recovery this year into a brief peak next year. But consider how much has to go right, for that to happen. The IEA sees next year’s product demand at 99.453 mbpd compared to 99.725 mbpd in 2019, 91.053 mbpd in 2020 (the pandemic year), and 96.447 mbpd this year. What hope does global petroleum product demand have in 2023 of surpassing 2022? Precious little. By then, global changes in workplace routines will be landing with considerable impact, and global EV adoption will be ferocious.

The Gregor Letter tips its cap to oil traders who successfully played the year long rally. Hopefully those same traders understand why momentum is now starting to evaporate. The forward looking rate of change in demand has slowed considerably. The roughly 5.5 mbpd gain in demand this year will be followed, supposedly, by roughly 3.0 mbpd of growth next year. But frankly, there are risks to that advance, and The Gregor Letter is starting to sour on the prospects for 2022. Indeed, The Gregor Letter remains with the view that oil demand growth will rebound by a stronger than expected 6.00-6.25 mbpd this year, thus stealing further momentum from next year. Remember, now that oil has peaked (as coal did in 2013) oil is just a trade.

It’s important to not interpret the pandemic’s hulk-smash! of the oil market as confirmation of oil’s demise. Rather, we should interpret the pandemic as a unique event that arrived just as oil growth was already leveling off. And accordingly, 2020 will likely be seen decades from now as a crucial pivot in the Oil Age, one as significant as WW2 which initiated oil’s inevitable dominance over coal.

When you look at the chart below, therefore, look at the longer term weakness in OECD demand, and imagine yourself, say, in 2015 asking the following question: I wonder what confluence of events would finally trigger oil’s decline? We mostly have our answer: a worldwide pandemic that fundamentally alters commuting habits and which arrives just as EV are starting to take off. As with all complex questions, uncovering the answers is devilishly hard at the front end, but maddeningly simple and obvious afterwards.

When it comes to the global oil market, we are now finally getting our answers.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.