Midyear Chartbook I

Monday 11 July 2022

For more than a decade, dividing the world into two spheres of oil consumption has been a useful way to think about the evolution—and the future—of global oil demand. The OECD came into its consumption peak 17 years ago at roughly 50 million barrels a day (mbpd) and since that time has steadily traded places with the Non-OECD. Now it’s the Non-OECD that consumes more than 50 mbpd while the OECD travels along at the 45 mbpd level. 2019 still stands as our last and best year for data comparisons, and Non-OECD and OECD demand stood at 51.68 and 46.07 mbpd respectively, in that year.

Now let’s consider 2021, the first rebound year from the pandemic. The chart here comes via the latest release of the BP Statistical Review covering data through 2021. Notice how Non-OECD demand in 2021 recovered to a level that’s 99% of its 2019 high. Not so much though for the OECD, where 2021 demand recovered to just 93% of the 2019 high. Why is that? And is this pattern already familiar to us? Is it something we should have expected? Yes, to all those questions.

If you look back to the great recession, you’ll see that particular crisis triggered a permanent step down in OECD demand. That’s because a solid portion of OECD demand then, and now, is discretionary. The OECD countries are the original oil hogs, led of course by the United States. Oil demand in this sphere of the world contains a significant Leisure & Convenience component. Oh damn, I forgot the whipping cream at the store. And soon, a 6000 pound SUV makes its seventh suburban round trip of the day. In the OECD, recessions and crises hit travel and leisure hard. Should we expect this to repeat? We should.

The OECD also happens to be a sphere where efficiency gains tend to proceed at a pretty good pace. Europe for example is the main driver for these gains. But across the entire OECD the painful memory of high oil prices during a crisis tends to unleash fresh rounds of efficiency. It happened after the OPEC oil embargoes. It happened after the great recession, and it’s probably going to happen again. That 46 mbpd level will likely mark the peak of the next step down. And just to remind: EV adoption was not yet a thing, in all previous energy shocks and associated financial smackdowns.

It must also be remembered that per capita energy use more generally in the OECD remains extremely high. Think of this as excess waste, a high level of inventory that makes sustained trimming of consumption more feasible.

Oil demand in the Non-OECD by contrast is coming up from a low base, just like its broader energy demand. Individuals in the Non-OECD are also far less price sensitive, in part, because each individual uses less energy generally, and that user profile applies also to oil consumption. If you own a 2 or 3 wheeler, and only consume several liters of petrol per month, it just doesn’t matter as much if oil prices are at $80, or $120.

The Gregor Letter maintains its view that global oil consumption has now peaked, around the 2019 high. This view is often misunderstood as implying that global oil demand is about to decline. Nope. There is little prospect that global oil demand goes into decline because the Non-OECD keeps finding ways to outrun the OECD demand decline. Eventually though—perhaps over the next 3-7 years—a sustained decline will finally appear. One of the reasons for that outcome is that the OECD, which held demand steady for a decade, is about to perform another step down. And so the Non-OECD’s ability to outrun the OECD decline is about to get harder, alot harder. Especially when you consider the wild rate of EV adoption in the Non-OECD’s most important economy, China.

For those who suffer either/or syndrome, who find it challenging to contemplate a plateau of global oil consumption, just remember that the oil industry also sees this end of growth and is similarly challenged to formulate a response. How does one invest heavily in future supply, if a supermajor like BP keeps producing a forecast that no demand growth globally occurs after 2025? Remember, it wasn’t Greta Thunberg or ESG investing mandates that got us here. The threat of a secular slowdown in global oil demand growth began almost ten years ago, in 2014, when global supermajor investment dropped off markedly, with a profound and damaging impact on the oil services sector.

In the years ahead, it will be far more useful for investors to ignore the warped thinking of political partisanship that only seeks to place blame for the current situation, and instead concentrate hard on the following: what if oil supply remains tight in a no-growth oil demand world, because, collectively the global oil industry has absorbed and accepted that there’s no growth up ahead to capture?

Combined generation from global wind and solar has now surpassed nuclear power. This chart tends to stir controversy, because nuclear itself tends to stir controversy. There’s a sturdy community of nuclear advocates who’ve spent decades tearing their hair out because the west has, in fact, dropped the ball on nuclear. They see this as illogical, innumerate, and perhaps a little bizarre. Just to remind, The Gregor Letter remains an advocate of building some new nuclear to reflect the fact that dense, coastal populations are harder to serve by wind and solar. And more broadly, because using nuclear as a tool to enhance and preserve the buildout of clean energy would be an effective, smart thing to do. Let’s build new nuclear! Let’s do it.

But nuclear advocates who go beyond these more limited ambitions need to finally face up to some truths. Here are the main ones: wind, solar, and storage (WSS) are cheaper, better and most important of all, faster. If your goal is to combine return on investment with solutions that work quickly on decarbonization, then WSS is unbeatable. Again, look at the chart. Consider the speed. Why is there such a differential in speed?

Because nuclear faces, and has always faced, a social hurdle. That social hurdle is absolutely punishing to nuclear’s return on investment prospects because it greatly slows planning, permitting and construction timelines. Nuclear projects tend to be catastrophic cost overrun boondoggles, and nuclear advocates habitually respond with if only society was more damn rational we could build nuclear faster. But society is not rational. It doesn’t do the math that Mr. Cocktail Party Engineer Guy likes to flog, because society has major concerns—many legitimate, some less so—about nuclear’s proximity to their homes, and especially the problem of nuclear waste. Did you know that US nuclear plants have been effectively transformed over the decades into de facto nuclear waste sites? How would you like to stare across Plymouth Bay to the now de-commissioned Pilgrim Plant, which no longer produces power but is a toxic waste dump? A role that was never conceived of when US nuclear plants were originally proposed.

Just deal with it. The chart above therefore also largely tracks the enormous differential in social hurdles between nuclear and WSS. The latter is being built out across the farms of Iowa, the drylands of the American southwest, and soon offshore the eastern seaboard from Boston to Richmond. Stop fighting it. Stop saying it’s illogical. But most of all, please stop saying WSS won’t scale.

You are reading a two-part post from The Gregor Letter, the first of which is free. Part II will publish between the regular schedule on Monday, 18 July. If you are still carrying a free subscription to the letter, please consider subscribing. Here’s why: there are few free posts throughout the year. Moreover, subscription rates are a very reasonable $75.00 per year for individuals and have not been raised for some time. Yes, inflation is still transitory. To learn more, see the About section. Many thanks as always to the international institutions, agencies, and investment professionals who rely on the letter for its analysis.

The volume of global power now generated by combined wind and solar matches total EU power generation, from all sources. Numbers can be fun sometimes:

2894.4 TWh: global wind and solar generation in 2021.

2895.3 TWh: total EU power generation from all sources in 2021.

There’s no longer any excuse for nonsensical talk about wind and solar. How they can’t scale. How they are too expensive. How they’ve barely made a difference. The two renewables combined have become a major force in global power generation. As you can see in the chart below, combined wind and solar have now crossed the 10% share threshold globally and in China; the 12% level in the United States; and nearly the 20% level in the EU. California and the UK remain global leaders at the 25% level, or above.

Global fossil fuel consumption is not set to decline anytime soon. And even if we plod along on an oscillating plateau, it’s still very bad news for climate. The storyline of the world’s decarbonization efforts continues to be a tale of two cities. On one hand, EV adoption is soaring in China and the EU, as clean electricity is also growing very fast now and at scale—as the previous charts attest. Yes, it’s happening: new electricity demand from EV in China, the EU, and the US is all more than covered by marginal growth of clean electricity from renewables.

But that that does not mean fossil fuel consumption is being damaged much at all—apart from its dimming growth prospects. One way to see the world’s current position is that clean energy is significantly blunting the growth of fossil fuel consumption, but not yet able to kick fossil fuels to the curb. Global coal peaked 8 years ago in 2014, but has mostly plateaued since. The same fate awaits the 2019 peak for global oil: growth prospects are scant, but any outright demand decline is not visible either. Finally, natural gas continues to find its way into every gap in the global economy, and is on course to continue growing strongly. Structural note: until grid level storage really starts to take off, natural gas will be a kind of partner to renewables—supporting the gaps to their intermittency. Renewable advocates are not keen to admit this truth. It is unpleasant. But operationally, it’s true. Gas fired power plants and the ramping ability of their modern turbines have been growing strongly alongside wind and solar, paving the way for wind and solar’s higher levels of penetration. Look at the data in the previous chart for the UK, for example, where generation from wind and solar (mostly wind, in the UK) actually fell back to a roughly 25% share last year from a 28% share in 2020. Those annual levels would not be attainable without some fossil generation in support.

The bracing chart above, which combines oil, natural gas, and coal shows that even when one fossil fuel falters, the others pick up the slack. Oil rebounded strongly last year but from deep lows, and didn’t come close at all to its 2019 highs. But when dumped into the fossil fuel mix, oil barely acted as a drag on total fossil fuel consumption. That’s because coal rebounded to levels last year that are extremely concerning (more on that, to come). And as mentioned, natural gas continues to grow strongly. Warning and reminder, this chart terminates at year end 2021, and this year total fossil fuel consumption is sure to breakout above the 2019 level because oil consumption, although weak, continues to push slightly higher and coal is being called upon again as the Russian attack on Ukraine continues to foul up energy flows of natural gas via LNG. The tale of two cities is not improving. There will be some soul-searching in 2023 about how the 2021-2022 energy crunch unleashed a fair amount of backsliding into the morass of fossil fuels.

Coal consumption in 2021 was so strong, that it wiped out every year of progress since the peak of 2014. Time to face up. One of the dynamics that climate scientists have warned about for years is the spare capacity latent in the enormous coal fleet of China. Yes, China is the global leader in the buildout of new wind, new solar, and adoption of electric vehicles. China is also pursuing a new offshore wind industry, and doing so very aggressively. However. China’s coal fleet was amassed over decades, and when cold temperatures strike in winter, or a global LNG supply chain problem develops, China can always turn to coal as a back up.

Just to put some further details on the chart above: China’s coal consumption had been roughly stabilizing around 80-82 EJ since the global peak in 2014. But last year China’s coal use leapt higher, to just above 86 EJ. And again, this was despite another titanic year in China’s buildout of wind and solar.

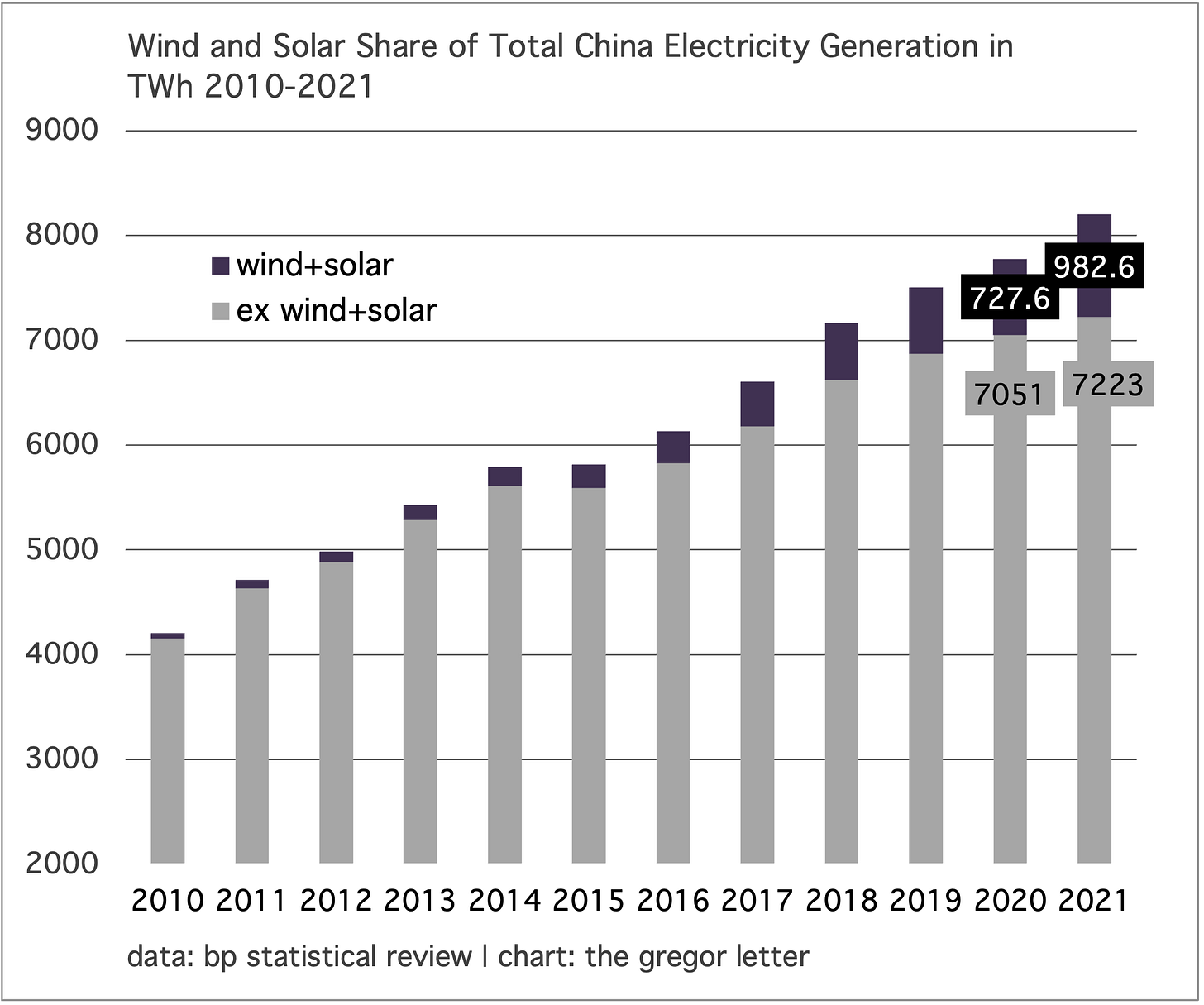

In China’s power data therefore, we are still waiting for an encouraging easter egg, if one can use that term: a phase when wind and solar begin to take control of marginal growth. Are we near? Well, there are encouraging signs. While power generation from sources ex wind+solar grew by 172 TWh last year, wind+solar grew by an astonishing 255 TWh. To put that in context, China added enough wind and solar in a single year to generate nearly as much power as Spain generates from all sources (272 TWh).

But there is an even more impressive comparison. At 982 TWh, China is creating clean electricity from wind and solar at a level that matches the total output of power generation from Mexico and Canada combined (977 TWh).

Just to review your summer cocktail party talking points:

The world now produces from wind and solar in a single year an amount of electricity exactly equal to all the electricity the EU produces from all sources.

China now produces from wind and solar in a single year an amount of electricity exactly equal to all the electricity Mexico and Canada together produce from all sources.

—Gregor Macdonald

Data notes: All data in today’s letter comes from the just published BP Statistical Review of 2022, which covers global data through the year 2021. The common energy unit used now is the exajoule. This may be frustrating to those used to barrels, or tonnes. But let’s remember that when measuring energy, heat units are preferable. The one data series not from BP in today’s letter covers California, which comes from the EIA, and is crossed checked with State of California reporting. Here, the data is less precise, owing to the hurdles which EIA has erected in recent years, by shutting down useable portions of their Open Data project. This forces users to grapple instead with overly large Excel spreadsheets. If this sounds like a complaint, it is. :-) The Gregor Letter continues to lobby EIA to restore the user friendliness it established under the Obama Administration.