Multipliers

Monday 21 August 2023

The Inflation Reduction Act is so quickly embedding itself into the US economy that its terms are unlikely to be altered by any future administration. To investors and observers outside the United States—who’ve witnessed American policy succumb over decades to the dramatic push-pull between the two major political parties—this proposition may sound risky. But the IRA has a number of organic protections now gathering around its base. By the time the next window of policy risk arrives, after the 2024 election, the benefits of the policy will simply be too widespread. Few, if any, will dare to disrupt it.

The most powerful and enduring feature of the IRA is that it’s acting, and will continue to act, as a catalyst for investment capital that’s now arriving from the rest of the world. The Gregor Letter has sounded out this theme previously, pointing out the strong advance in FDI starting in 2021, and explaining the IRA was set to trigger an enduring multiplier effect. Many are now starting to quantify that effect. Earlier this year, Goldman Sachs speculated that the legislation could wind up attracting $11 trillion of infrastructure investments by the year 2050. More recently, the Financial Times estimated that the IRA, in conjunction with the CHIPS Act, had already unleashed over 110 large scale industrial announcements, amounting to more than $224 billion in projects. And of course, we’re just getting started.

Republicans have been blindsided by the unexpected way in which the IRA, the CHIPS Act, and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill have rolled out. They did not expect the bulk of investments, so far, would have such an outsized impact on their own congressional districts, in deep red states. But neither did they expect the suite of legislation to act like a powerful attractor to private capital. In this, they were not alone, and it’s worth explaining why. You see, the United States is a country that’s neglected to build needed infrastructure for forty years now. Whatever muscle was built up in the late 19th and 20th centuries has completely atrophied. We don’t even know how to talk about infrastructure, how to cover it journalistically, how to promote its return on investment, or to analyze the losses to US GDP from the infrastructure deficit, and its crimp on productivity. This is all reflected in the country’s inability to build anything well, from bike lanes to rail, without an enormous struggle resulting in sky high costs that lie completely outside the norm in the rest of the developed world. The atrophy is so widespread that the problem is actually obscured from the day to day American vision. The shock into reality typically comes, however, when Americans return home to confront their defunct airports, non-existent public transportation, and chaotic, poorly designed streets.

If you actually talked to infrastructure professionals the past decade—professors, engineers, policy wonks—they would have told you that for the country to get moving again it would never be sufficient for states, or private capital, to spark the needed change on their own. No. The federal government is crucial, because the logjam of regulation and rules, when busted at the federal level, finally creates a safe path for private capital, which typically fears project completion-risk. US politicians have lived for many years in a linear world, therefore, thinking about spending in static, zero-sum terms. With this sequence of legislation, the US has created for itself a kind of ongoing, countercyclical safety net that will plow through the next recession, and several recessions to come.

Now of course we have the rather hilarious spectacle of politicians in red states celebrating the job gains even though, as Republicans, they voted against all of these programs. Tim Scott, Republican from South Carolina and presidential candidate, has been singing the praises of material recycler Redwood Materials, and its decision to open operations in his state. But Redwood did so in part because of the IRA, and more generally the company has benefited from additional direct investments from the Department of Energy. Scott voted against the legislation, as a senator. And it’s worth recalling: not a single Republican member of the House voted for the IRA. Indeed, red states are so overwhelmingly the beneficiaries of this legislation that any future retorts to the IRA from electeds in these states will be composed entirely of hot air. The set-up is reminiscent of Obamacare: it was all well and good to rail against President Obama, but when actual Republican members of congress made their move to act against Obamacare, they got blowback.

Over 80% of investment flows have so far gone to red states, according to analysis from the FT. Over time, that mix will probably start to balance out. But it’s worth understanding another feature of the US landscape, when thinking about the real versus the perceived risk that anti-green politicians will try to attack the IRA in the future: many red states suffer from above average poverty. Indeed, red states are also victims of the forty year drought in US domestic investment. So, if you start parachuting semiconductor, battery, and EV plants into South Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky the economic sensitivity to that investment is going to be high. For future politicians who propose to halt that pipeline? Well, good luck.

Republicans need to find a new candidate to run for President in 2024, because the prospect that Trump improves on his 2020 performance is remote. Consensus analysis continues to scamper back to the heuristics of 2016, in which Trump upended the conventional wisdom and won 304 electoral votes (EV) despite losing the popular vote by 2.8 million. Very obviously, 2024 is not 2016 and it’s not 2020 either, in which Trump lost the popular vote by 7 million. The next twelve months meanwhile are set to be brutal for Trump’s political prospects, and that too remains insufficiently discounted. Public trials have a long history of shifting sentiment because courtrooms have a nasty habit of airing out the facts, while stomping on the nonsense. Courtrooms are where bullshit goes to die.

When thinking about 2024, it’s worth considering therefore how much Republican and Independent support Trump risks losing. Let’s be overly conservative and say that two thirds of 2020 Trump voters stick with him, regardless of his myriad legal jeopardies. Let’s also say the bulk of the final third sticks with him too. But of that final third, educated and professional Republicans in urban areas are likely to consider more deeply the absurdity of voting for a candidate out on bail.

If Trump loses just 5% of the vote he received in 2020, and Biden retains his vote, that would put two of the five closest states that Trump won last time into play: North Carolina, which Trump won by just 1.35%, and Florida, which he won by 3.36%. The next three states would be a harder get for Biden: Texas, which he lost by 5.58%; a single Maine electoral district which he lost by 7.44%; and finally Ohio, which he lost by 8.03%. These five states (well, four states and one EV district in Maine) are shown in gold color in the above EV map. The map itself is a duplicate outcome of the 2020 election, but applied to the 2024 apportionment after the last census, in which a net +3 EV accumulated to the Republican advantage. To make this crystal clear for readers outside the United States: if the results of the 2020 election were duplicated in 2024, Biden—who won 306 EV in 2020—would win just 303 EV in 2024.

As for the uncertainties about the Biden vote, one has to remember that if Trump is on the ballot, negative partisanship voting is activated, which means—to use a favorite phrase—that Democratic voters will be willing to crawl through glass to vote against Trump. In other words, Republicans lose the passion-vote among Trump supporters if Trump is not the presidential nominee, but at least they bring back suburban Republican voters who would not be embarrassed to vote for Tim Scott, Chris Christie, and other names not in the race yet, like Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin. Republicans, as you can see, are in a pickle. Their leading candidate is a unique kind of ticking time bomb: gathering up all the energy of the Republican base, but repelling voters needed to get him over the 270 EV threshold.

Yes, enthusiasm for Biden remains poor. But he is nowhere near as disliked as Trump. A recent AP poll showed that 64% of Americans are already certain they can’t vote for Trump. Thus, we have two pools of passion to track as we head into next year. One pool is the bottom third of Republicans who would vote for Trump even if he made animal cruelty videos. That represents about 17% of the electorate. But we have a very large portion of the electorate—Democrats, Independents—passionate to vote against Trump. Here, we can even posit that no Democrat is excited to vote for Joe Biden next year. Doesn’t matter: they will all pour out to vote for Joe as a way to negate Trump. But it’s good to acknowledge: a Biden win next year will be composed not of wild Democratic enthusiasm, but broad voter fear of a second Trump term.

Beware of oil analysts bearing convergence theory. After World War II, the United States began its long, transitional journey from an industrial economy to a consumer economy. Because this change of character began mid-century, and because so much economic activity in the postwar period was aligned with the building out of American suburbs, oil was the primary platform for growth. Between 1950 and 1970 for example, US oil consumption rose a heady 127%, from 6.5 mbpd to 14.7 mbpd.

This era of rapid energy growth still has a grip on the mind of many analysts, who make the mistake of believing that the Non-OECD in the 21st century will replicate the OECD experience of the 20th century. Apparently, it has not occurred to these analysts that electricity is the 21st century platform for economic growth, not oil. If you look at this per capita chart of oil use since 1965, for example, try to imagine OECD consumption eventually converging with Non-OECD consumption—as expressed by its two biggest economies, India and China. Where do analysts, bullish on future oil demand, think the point of convergence will land?

The Gregor Letter takes the view that China’s oil per capita advance over the past twenty years, up over 170% from 2000-2022, was in fact the advance analysts are now mistakenly looking for, up ahead. Other observers are understandably looking in a different direction: the end of road fuel growth in China, and perhaps even the end of oil demand growth. The head of CNOOC is actually entertaining this idea, and why not? China’s slowdown is composed of a number of long-term factors, from demographics to the tailing-off that naturally comes after your economy has gone through the most intense phase of industrialization. Xi’s economic policies have been bad for a while, and now it looks like those mistakes are finally landing.

Just a note on the units here: yes, it is unusual to see the kilowatt hour (kWh) used to measure liquid oil. But one explanation is that Oxford-hosted Our World in Data prefers to use this common unit over, say, joules or some other heat unit.

US total fossil fuel production from oil, natural gas, and coal is up an enormous 6.8% during the first four months of this year. Looking into the details reveals that coal production is maintaining its levels from last year, while natural gas, crude oil, and natural gas liquids are soaring. Just to remind: The Gregor Letter has repeatedly made the point that US fossil fuel production will increasingly decouple from domestic demand, now that petroleum products and LNG are so easily exported. Nice little detail on that issue: natural gas exports by land pipeline to Mexico have just hit a new all time high.

Form Energy, the iron-air storage company that’s already struck contracts in Colorado and Minnesota, has just made another deal to bring storage to New York State. Form’s technology aims for 100 hours of discharge time, which is characterized by company leaders as multi-day storage, or MDS. Quite obviously, if you have a grid sized battery that can discharge for 100 hours, versus the current standard of 4 hours for lithium-ion technology, then what you have is something that looks more like generation, than storage. Indeed, if several iron-air battery arrays were located in the same region, and the typical duration of gap-filling imbalances is 2-4 hours, then iron-air battery arrays would have so much time to recharge after partial discharge that we might almost think of MDS capability as continuous. In other words, when exactly would a 100 hour battery not be available?

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) announced the procurement last week. Readers might also want to take a look at Form Energy’s recent white paper, showing that longer duration storage is going to be more efficient and economical than the current short-duration (four hours, lithium-ion) standard. No question, that’s a corporate white paper that is self-serving—but sometimes it’s important to recognize that, if you find, say, a group of people working on long-duration storage, they probably arrived at that project because they believe it’s an optimal solution.

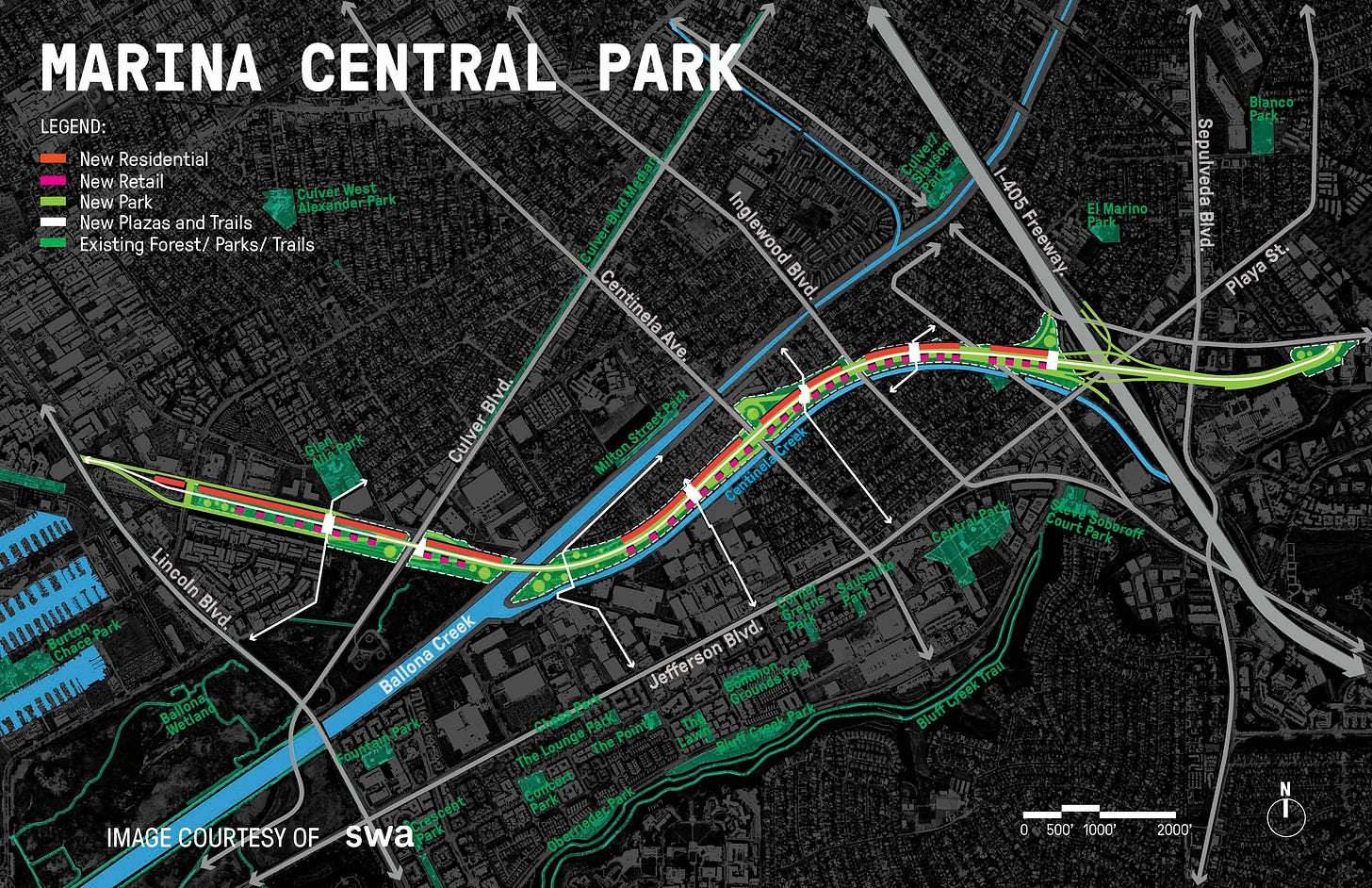

If closing and re-purposing streets and freeways is your jam, then you will love a mega-proposal now coming out of Los Angeles. Marina Central Park would transform the 90 freeway into a long necklace of residential structures, parks, bike paths, and a bus lane. This is precisely the kind of project needed to tackle the toughest emissions problem still facing the US: oil consumption in transportation.

—Gregor Macdonald