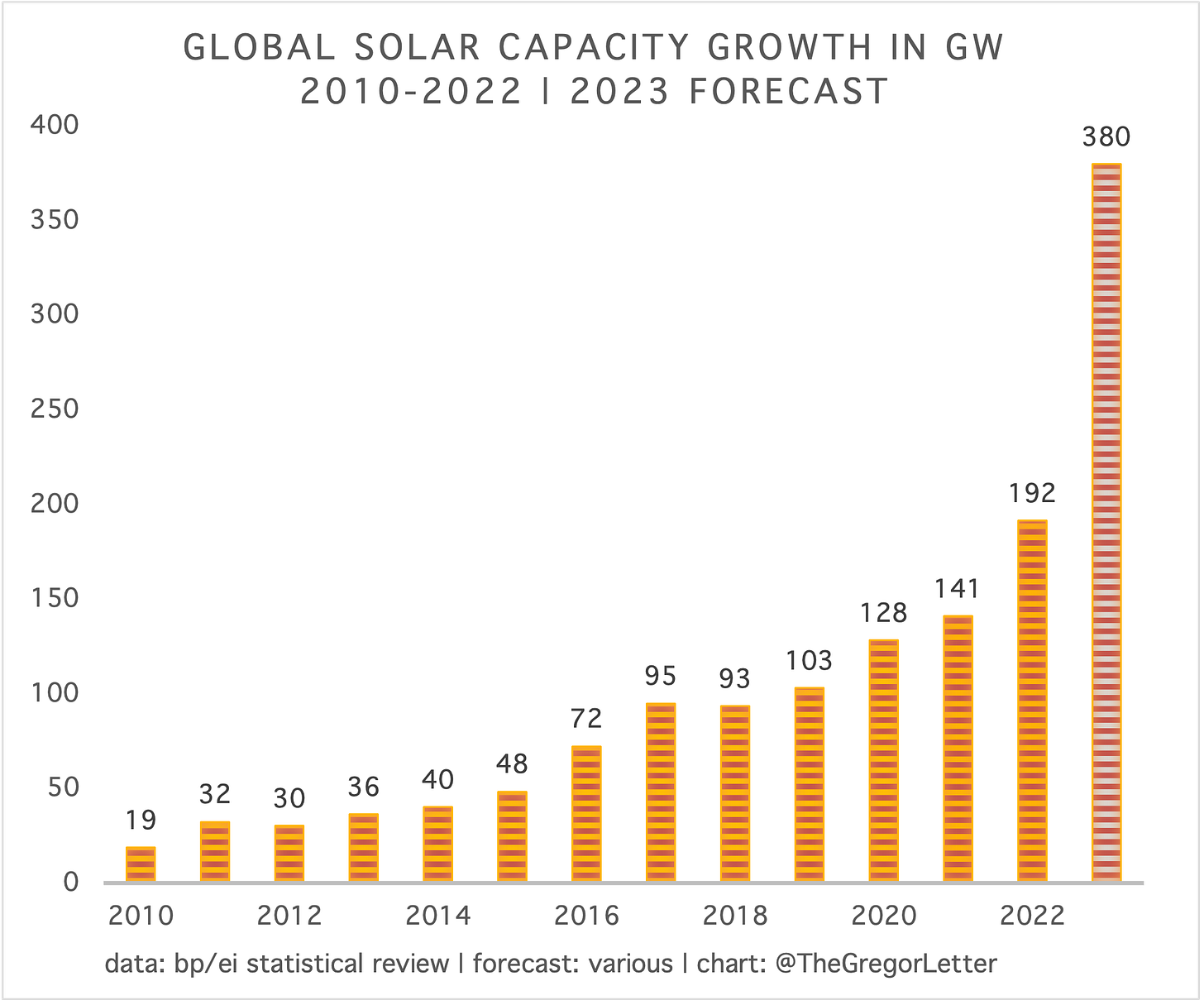

Solar capacity growth in China is on course to nearly double last year’s performance, once again kicking global solar into higher gear. According to reports, China has deployed 78.4 GW of fresh capacity through the first half of 2023. In all of calendar year 2022, China deployed 86 GW of new solar capacity, according to EI Statistical Review. At this year’s pace therefore, China is likely to deploy roughly 157 GW of new solar. Fantastic. To get a taste of how fast we’re growing, total GW of solar deployed globally in 2021 was 141 GW.

Using this data, let’s now speculate. Over the past 5-6 years, China’s contribution to annual global capacity growth has been amazingly steady, at around 35%. If this share obtains once again this year, we can project that total global additions will reach an incredible 448 GW. Is that just too easy? Probably. While patterns may appear at times during the energy transition, renewables growth is an upwardly volatile phenomenon, punctuating the grand curve with aggressive spikes and setbacks.

In this June’s Renewable Energy Market Update from the IEA, they estimate that total global renewable capacity growth this year will reach 440 GW—but that includes wind, hydro, and other small renewables categories. For solar specifically, IEA sees 287 GW of new solar deployed this year in their main case, and 327 GW in their accelerated case. While the IEA has made moderate improvement in their forecasting, they continue to be too cautious.

Other forecasters, like BNEF, are currently in a range of 320-380 GW. And there are a number of forecasts around that level. Given China’s extraordinary growth so far this year, we should probably favor the higher end, around 380 GW. But prepare yourself: we could see a 400 GW year in 2023.

Just to remind: The Gregor Letter overwhelmingly favors generation, rather than capacity, when discussing wind and solar growth. You should too. Generation, not capacity, is all we really care about. However, tracking capacity growth between the big data releases helps us get a handle on the generation outlook; one simply has to deflate wind and solar capacity additions to reflect that their up-time (capacity factor) is lower than other sources.

The high rate of growth we need from wind and solar is encouraging, and is achieving the rate we need to plausibly halt fossil fuel growth in global power by the end of the decade. Because the trajectory is so strong, it provides us with increasing clarity that generation from wind and solar could indeed triple from 2022 - 2030. This helpfully narrows down the uncertainty in the emissions problem to the growth rate of the underlying power system, most recently addressed in The Big Number, and in a follow up, the Monday Chart.

To put it simply, if global power grows at the trailing ten year average rate of 2.5%, then renewables, led by wind and solar, are on track to eat into underlying fossil fuels in the system. At 3.0% however that prospect becomes quite uncertain. And at 3.5%, out of reach. We should plan for a higher rate. Non-OECD power demand has grown at a 4.2% average over the past ten years. OECD growth has been alot slower. But the United States now looks like its own power demand is breaking out of a long plateau. And that should be no surprise. The reasoning of The Gregor Letter is informed by dynamics seen over the past fifteen years in the oil market: higher growth in the Non-OECD acts more like a fixed rate, with variability in weak OECD demand governing the annual total. If the OECD is now going to join the Non-OECD in higher demand growth for power—as we move transportation and other work over to the grid—then a higher global growth rate for power demand is on the way.

EV continue to grow their market share as US vehicle sales recover. Based on data from the first half of this year, US light duty vehicle sales are on pace to reach 15.4 million, a 13% advance compared to the same period last year. But EV sales are not only on pace to reach 1.3 million sales compared to last year’s 900 thousand sales, but for the second year are achieving market share penetration well above 5.0%—the key take-off threshold in technological and product adoption.

We continue to get evidence that petrol demand in California has entered decline. The 12 June issue of The Gregor Letter went into some detail on all the factors that finally led to this tipping point. It wasn’t easy, or quick. Let’s condense those now into the most important points. After all, California has long been the leading edge of change in the US, and we should be aware of the signal now emanating from the Golden State.

The two dominant factors necessary to force road fuel demand into decline are as follows. 1. The years that have passed since ICE sales peaked in a particular domain. 2. The market share of EV in new vehicle sales in that domain. Yes, there are many other factors that matter: population shifts, petrol taxes and other incentive schemes for EV, and changes in commuting patterns, like work-from-home. But ICE sales in California peaked at 2.153 million in 2015 (falling to 1.5 million last year) and EV are on course to take 20% market share this year (having reached 18% last year).

Why the focus on the peak in ICE sales? Well, the average lifespan now for a new ICE vehicle has reached a record 12.2 years. Getting at least halfway through those twelve years means stacking up six consecutive years of declining ICE sales. Notice that when petrol demand rebounded both in 2021 and 2022, it did so to lower levels—six and seven years after the 2015 ICE sales peak. Because all marginal growth in vehicle sales since 2015 have been controlled by EV, that peak cohort of ICE sales are starting to age, and may start to roll off into the used car market, while a small percentage will retire. In addition, California DMV data shows the total existing fleet of ICE cars, which continued to grow after 2015 (as expected, yes, even after peak) eventually began to struggle around 26 million, reached 27 million in 2021, and then fell back last year to 26 million again. All this said, do not expect the petrol decline to be rapid.

What does this tell us about the US as a whole? ICE sales peaked nationally in 2016 at 17.3 million. By last year, they had fallen to 12.8 million and are slightly rebounding this year, to potentially reach 13.5 million. But, as we saw in the previous chart, EV market share, while encouraging, is still below 10%. That’s not enough. Mind you, US petrol demand, like US oil demand, has been on an oscillating plateau for many years. We long since departed the era of growth. Instead, we are grappling with the plateau problem: the very hard work required to get fossil fuel consumption off a stubborn ledge, and into decline.

A large volume of US emissions lies almost entirely within Democratic control, and these domains are also failing to take action on vehicle emissions from the existing fleet. It’s time to get liberated from the oft-repeated claim that only Republicans are in the way of climate progress. That’s already well known, and understood. As Dave Chappelle might say, “we been on that.” The US has multiple cities—many of them vast conurbations—where policy is controlled entirely by Democrats, all the way from city councils and mayors up through the governor and the current administration.

We were reminded of this just last week as Governor Murphy of New Jersey went beyond verbal castigation of New York City’s congestion charging plan, and actually filed a lawsuit. Folks, if deep blue states with Democratic governors and mayors cannot find a way to enact congestion charging in New York City! that’s a tell. Just to remind, transportation today is the top emissions source in the US, now that we are rapidly decarbonizing electricity.

Over 52 million people, or a bit less than 1/6th of the country, live in the three large states of the west coast, a vast expanse controlled by Democratic governors, key Democratic mayors, and deep blue Democratic voters. Contained therein are two large cities, Seattle and Portland, topped off by two massive conurbations: The SF Bay Area, and Los Angeles-Long Beach-Orange County-San Diego. The US DOT could greenlight at any time congestion charge programs from Seattle to Portland, SF Bay to SoCal. All that’s required is for the overwhelmingly Democratic electorate of these cities to ask for it. Ouch. And the same goes true for Chicago, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. The Gregor Letter publishes from one of these cities, a global epicenter of progressive liberalism: Portland, Oregon. You would need an investigative team to find a Republican here. And yet, we are a tattered mess around everything having to do with cars, highways, and the reduction of vehicle emissions. On the table for years here in Portland has been an unwise freeway widening project to solve a problem that could be far more quickly, efficiently, and less expensively solved with congestion charging. Good grief, said Charlie Brown.

Shoutout to NoMoreFreeways, a local group that understands cars, roads, and highways are the central distribution mechanism for oil consumption. Their motto is perfection: Climate Leaders Don’t Widen Highways.

A simple but important insight from environmental economics is that the economy is a subset of nature, and not the other way around. Because we are a species increasingly adept at the transformation of nature, it’s understandable that humans might evolve to conclude that nature itself is a subset of the economy—you know, like a small grove of lemon trees gracing the perimeter of Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino. But no, as it turns out, without nature Apple’s clever consumer devices don’t exist either, nor do the people to purchase them. Playing around with these two views, you can glimpse how human beings are inclined to think: nature operates in the background, constantly refreshing its supply for our benefit, and we can therefore pluck as many lemons as we like—for we are the ones in charge.

Financial markets, in this same landscape, are the place where we record, and in indeed store the wealth, that flows from nature. And financial markets, always and everywhere composed of humans, have come to depend on this constant refresh rate of inputs to the economy. Depend? Yes. But assume is also important here. Humans assume the refresh rate of nature is a law. Well, it was, until the climate started changing. And now we have a problem. Or rather two problems: nature itself is under extreme pressure, and the place where we record nature’s health is not reflecting that pressure.

In 2021 Professor Madison Condon, of Boston University Law School, published Market Myopia's Climate Bubble, a grand tour of the myriad ways financial markets have yet to price in future constraints, and future losses, from climate change. Comprehensive in scope, Condon’s paper takes a let me count the ways approach and finds the mispricings, unsurprisingly, can be found top to bottom, from instruments that reflect prospects for states or cities, like municipal bonds, to risk accumulating for individual companies. The implications for individuals who store their wealth in financial markets and retirement plans are rather obvious. Or should I say, ominous.

Condon’s paper quite productively intermixes modern insights from behavioral psychology, and the incentives that drive individuals within institutions and the broader financial sector to avoid more accurate pricing. One important phenomenon highlighted is that markets do not reprice gently. Indeed. Humans are the products of evolution, and as a result we are reliably deep-discounters of the future. That is, we care about and make efforts around desires and risks in the near term, while making fewer plans and preparations for the future. This is partly why markets rarely reprice risk slowly over time, but tend to do so in a rapid woosh!

Cognitive conservatism is another useful term that applies here, and simply describes the human tendency to discount new information that disconfirms current beliefs, until those beliefs can no longer withstand the onslaught. Condon recounts the collapse of Pacific Gas and Electric, how that company’s share price lost 80% of its value in just two months. What’s helpful to think about is that this is how humans do it, expressing their psychology through markets. In the years leading up to PG&E’s 2019 collapse, evidence of a mega-drought in the western US had been accumulating for a while: steep drop-offs in California’s hydro output, cities smoked out in summer from Los Angeles to Portland. The reason that markets reprice in a flash, rather than over time, is that markets reflect how humans process information.

If nature’s wealth is starting to erode, then our future expected profits are not going to arrive as expected. You can actually think of profit in biological terms. The beaver expends effort to build a dam, and in the process secures a viable home while creating a back-up pond that flowers with renewed diversity—from which they also benefit. A more simple example: the cheetah expends energy to chase and catch smaller prey. As long as the energy consumed is greater than the energy expended, the cheetah enjoys a caloric profit, and lives to hunt another day. But as Woody Allen might say, “what we have here is a dead cheetah.” (see: Annie Hall, a relationship is like a shark, it must always be moving forward, and what we have here is a dead shark.)

Coming back around to a topic often covered here, Condon also addresses the likelihood that some portion of 20th century infrastructure will increasingly find itself…let’s use a British term here: unfit for purpose. Rail lines buckle. Pipelines fail. Utility transmission lines start forest fires. Corporate property gets flooded. And so on. Problems with grid stability in both California and Texas for example has led persons of a certain political persuasion to conclude that EV coming on to the grid must be the cause of blackouts, in addition to the variability of wind and solar. But it’s wind and solar, built in the 21st century, that are actually saving Texas and California from problems with their 20th century infrastructure. Notice the duration problem again in human psychology: no, it must be these recent things I see like wind farms and EV that are doing it, not the big wheel that’s been turning for decades, and is now causing temperatures to bust out of long contained envelopes.

If you are interested in how systems collapse, you may also have read the work of Joseph Tainter, who described collapse as a kind of rapid simplification from a state of complexity. In Tainter’s analysis, we are clever humans who build complexity but run into a problem when returns from investing in that complexity begin to diminish. Contemporary society is wildly complex, and supports a dizzying array of jobs from yoga instructors to computer engineers, and museum curators. This cornucopia of complexity is wonderful in every way, but as a system it’s vulnerable to pressure that would erode our profit from nature. A complex system like ours without question assumes the refresh-rate of nature is steady, and robust.

Solutions to better climate-risk pricing are perhaps easier to contemplate, than realize. Market Myopia's Climate Bubble understandably recommends an array of better and fuller disclosures that would more routinely be generated from the financial sector. One wonders though: if the same humans who find it hard to take action in the present to better negotiate the future are given more information about climate risks, would that change behavior? The economist Richard Thaler thought deeply about this problem, and in one domain suggested that the solution to workers habitually failing to invest for retirement would be to automatically enroll them in such plans, and let them opt out, rather than offering the workers the decision to opt in. There are kernels of insight there: humans are likely greeted with an internal barrier that’s hard to get over, when faced with making decisions about the future. Putting them into the future somewhat mechanically may force them, if only for a moment, to look back on the present. How can we encourage this type of thinking?

There’s an old trader’s adage that applies to the onset of any crisis: he who panics first, panics best. In other words, when capital is at risk, it’s preferable to slingshot yourself as best you can into the future, and consider your position today from that distant vantage point. If you recognize your enjoyment of nature’s wealth today, and would also like to be financially wealthy in the future, perhaps you should from time to time, without actual panic, consider that your plans are at risk.

Temperatures across the cities of North Africa are once again set to match or break records. Tunis, Tunisia today is expected to reach 49C or 121F, for example, as the month of July continues its blistering run, producing the hottest global temperatures on record. Let’s look back on Tunis, or rather Carthage, from the future. Below is the ingenious port, depicted as it was, paired with today’s map of coastal Tunis, still bearing the port’s remnants by the sea. Contemplate how Hannibal and his military, whose feats of daring are legendary, would have fared at 49-50C.

—Gregor Macdonald

Errrors and Omissions: the US EV sales chart that went out in the original email has all the correct data but the legend reversed. Now fixed.