New Material

Monday 6 January 2025

For the past five years wind and solar have done an exceptional job of suppressing the (net) growth of fossil fuels in US power generation. However, the risk that’s now emerging—given the race to source new power demand to support the growth of AI—is that natural gas growth, already a problem, does a hard acceleration. Why might that happen? Two reasons. The bulk of global data center capacity growth is going to be concentrated in the US, at least in the near term. And also, the volume of new power generation that the commercial technology sector is going to demand may smooth out eventually, but at the front end will be sudden. We are at the front end right now. This raises the likelihood that on-site natural gas generation becomes the go-to solution for the industry. Think: mini, dedicated natural gas turbine arrays that potentially sit behind-the-meter (BTM) and thus avoid the entire traditional process by which new, standalone on-grid powerplants are built. Indeed, big tech is about to join the list of justifiably frustrated interests in the US—wind and solar developers especially—who are ready to expand the grid, but cannot do so because of legacy regulation.

As you can see in the chart below, energy sources in the US electricity system ex wind+solar have been held in check for five years now at roughly 3600 TWh, starting in 2020 and running through 2024. That’s a great demonstration of wind and solar’s rapid growth, but also the hard problem of getting legacy generation to actually decline. This risk presented now, however, is that wind+solar may not be able to respond as quickly to sudden demand growth. If that happens, net generation from fossil fuels in US power will actually start increasing again.

The terms of this newly arising dilemma are becoming clear(er) as a number of very good analysts are stepping up to the plate to provide guidance. For example, if the tech industry is going to build on-site generation, why not choose instead wind and solar and batteries, with a small amount of natural gas as back-up? That was the question answered by a consortium of researchers last month, publishing at the URL of offgrid.ai, who found that off-grid solar microgrids would not just be economic to deploy, but could meet the speed the industry requires. Notably, this research got push-back from some quarters for even daring to raise the prospect that natgas would be paired to such systems. But the tech industry is going to preference reliability and security, so we should be so lucky if solar with natgas and battery backup emerges as the common solution. Just to remind: Germany’s long term national energy strategy is to have a modern grid that’s mainly powered by renewables but nevertheless has a good chunk of natgas back up. That’s a good benchmark.

Meanwhile, there is legitimate uncertainty about high-case projections for total power demand given the historical pattern in semiconductor manufacturing that sees processing power increase as energy requirements fall. This is a tricky set of factors to weigh, of course, because if a domain such as the US experiences rapid volume growth in data center capacity, that could overwhelm, in the short-term, future gains to computational efficiency. On this question, Micheal Liebreich has juggled a basket of uncertainties and has produced not a definitive answer, but an enormously helpful map of the terrain, if you will, and you should read his essay The Power and the Glory. There's alot of position-taking right now on the emerging AI/powergrid landscape that's overly strong and premature. Liebreich’s essay respects the competing concerns, and offers an excellent platform for how to think about the problem as we head into a very active year for global AI growth.

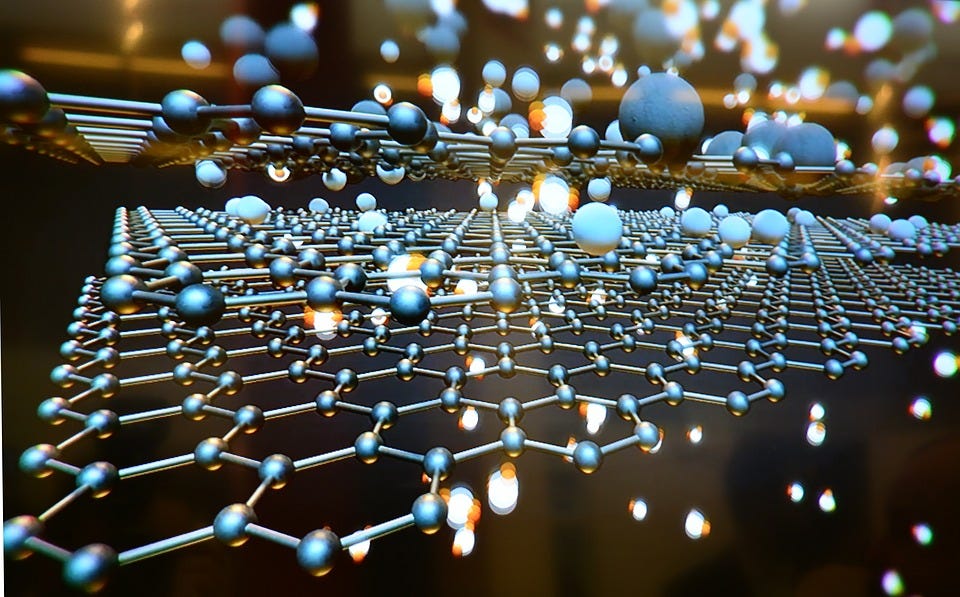

Working with an existing materials science lab, an MIT researcher discovered that the introduction of an AI tool significantly raised the lab’s productivity. From the recent story in the Wall Street Journal:

The lab that Toner-Rodgers studied randomly assigned teams of researchers to start using the tool in three waves, starting in May 2022. After Toner-Rodgers approached the lab, it agreed to work with him but didn’t want its identity disclosed.

What Toner-Rodgers found was striking: After the tool was implemented, researchers discovered 44% more materials, their patent filings rose by 39% and there was a 17% increase in new product prototypes. Contrary to concerns that using AI for scientific research might lead to a “streetlight effect”—hitting on the most obvious solutions rather than the best ones—there were more novel compounds than what the scientists discovered before using AI.

Toner-Rodgers was a bit surprised himself. He had thought at best it would have just kept up with the scientists on novel discoveries. “You could have come up with a bunch of lame materials that are not actually helpful,” he said.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cold Eye Earth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.