Of Interest

Monday 11 January 2021

US interest rates rose significantly as the global reflation trade gathered momentum. The yield on the US ten year government bond, which closed out last year at 0.91%, finished the week at 1.10%. The advance was part of an overall surge in industrial shares on global stock markets as the world prepares to reopen. One analyst on financial television quipped, “the economy is about to compress 18 months of production into less than a single year.” Germany’s DAX index, a perfect proxy for old school industrial growth, is already up +3.50% while hitting a new high. The MXI ETF, a common index of materials stocks (think: chemicals, copper, and iron ore) is up over 7% in the new year. Unsurprisingly, gold was hit particularly hard. But, by suffering heavy losses, gold provided helpful confirmation that interest rates have seen their lows, and an expanding opportunity set lies ahead for traditional investment. Contrary to common views gold thrives on deflation, not inflation. And this gold bull market may have just died on the back of imminent, economic growth.

Democrats pulled off an improbable win in the State of Georgia, taking both senate seats, thereby unseating Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. The victories added further fuel to the reflation trade, as every market analyst from Singapore to Oslo understands Democrats intend to make aggressive investments to get the US labor market back to rude health. At the weekend, President-elect Biden confirmed the thesis, saying, "Every major economist thinks we should be investing in deficit spending in order to generate economic growth…if we don't act now things will get much worse, and harder to get out of the hole later. So we have to invest now." While the double victories in Georgia take the Democrats to the thinnest version of senate control—50 seats + 1 with Vice President Harris—it’s not impossible Democrats could wind up with 51 (effective) seats. How so? The shocking events of 6 January, when the Capitol was assaulted by pro-Trump forces, is already pushing one Republican senator away from the party. Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski, in a remarkable interview with her home state newspaper, demanded that Trump resign and added the following thought to her remarks, “But I will tell you, if the Republican Party has become nothing more than the party of Trump, I sincerely question whether this is the party for me.” While no one expects Murkowski to become a Democrat, she appeared to open the door to joining Angus King of Maine, and Bernie Sanders of Vermont, as an independent.

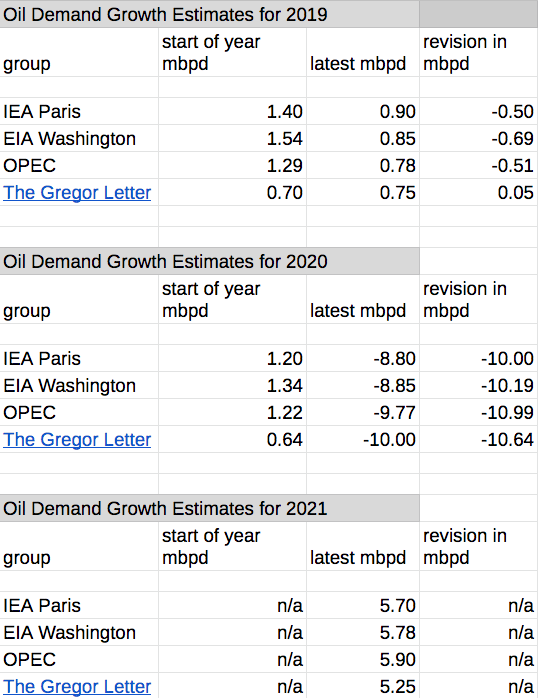

Oil and coal prices are rising as gasoline consumption advances, and industrial production returns to Asia. IEA Paris expects Chinese oil demand to have its biggest jump since 2010, rising by .85 mpbd this year. Cold weather across Asia is also driving demand and prices for coal and natural gas. However, we must remember that global oil demand will not reach 2019 levels this year. The plateau in global oil demand has begun, and now we wait for the declines to set in. Helpfully, 2019 stands as a convenient reference point for global oil demand at roughly 100 mbpd: EIA Washington is using 101.23 mbpd, EIA Paris is using 100 mbpd, and OPEC is using 99.76 mbpd. Depending on your forecast of choice, global oil demand will of course rebound strongly this year, but will only reach 95.00 - 97.00 mbpd. Let’s take a look at those forecasts, and also the Gregor Letter 2021 outlook.

Using the IEA Paris data as a baseline (because they use the very convenient 100 mbpd for 2019 demand), The Gregor Letter is slightly increasing the estimate of this year’s rebound from 5.00 to 5.25 mbpd. I agree with the IEA that jet fuel demand will remain under pressure for a long while, for example. But with measures of industrial activity already rising strongly in Asia, Europe, and now the US, it’s inevitable that road fuel demand will keep upward pressure on prices. While it’s disheartening to say so, we must remember that the global economic recovery will rebound on the back of the currently installed base of ICE cars and trucks. To be sure, as oil prices mount a further rally, those prices will also run into a change in workplace commuting, and the growing world fleet of EV. That’s enough to confidently forecast global oil demand will not reach the 2019 high this year. But the swing, or the delta, as demand moves up from around 91.00 to 96.00 mbpd is a good proxy and a good measurement of how much the existing system is still running on oil.

The crucial test comes next year when the global economy, having gathered momentum, places further pressure on the installed base. A quick take: if China’s EV sales continue their incredibly strong rebound this year, and adoption curves keep going as they are for EV in Europe, and Americans (who are not adopting EV as quickly) maintain marginal shifts in their commuting habits, then 2022 may see only a 1.00 to 2.00 mbpd advance. For now, however, the 2021 rebound is probably enough to meaningfully help the petroleum product segment of the market, but not enough to rescue producers. There is simply too much oil capacity now in the world, and OPEC’s tactic to run down inventories is understandable, but will have no lasting effect. The oil business is now a no-growth business. On that theme alone, please see this recent NYTimes piece telling the stories of recent graduates whose plans focused on the oil industry, and now must contend with a halt in hiring.

While interest rates have surely bottomed for the cycle, a post-pandemic world will likely keep them constrained for years. Applying further pressure to the pandemic’s aftermath is that the rate of population growth worldwide has been slowing down for decades as fertility rates continue to fall in nearly all high rate domains. Adding to the trend is that fertility rates in developed regions, already low, are falling further. The US for example just saw the lowest population growth in a century. Here is a chart from that linked article, from Brookings.

Energy transition will further act as a generally deflationary phenomenon, stripping out input costs to global production. Yes, energy transition will also place cyclical inflationary pressure on materials. Perhaps lithium, copper, silver, and steel will occasionally see supply-demand imbalances that drives prices into a short-term spikes. This will stir warnings from inflationistas that, finally, inflation is just around the corner. Indeed, we will probably see some inflation-like data points this year (and perhaps soon) as a rapid upsurge in demand hits the gradient of supply. But at the margin we are going to see a number of areas—from commercial office space to air travel, from commuting to household formation—where rebounds will be weak, and frankly, durably weak. The real question is whether the Federal Reserve, newly committed to letting inflation run hot while favoring labor market growth, can stick to its guns. Many bond market professionals are doubtful that the Fed will “see through” minor inflationary pressures, and will eventually capitulate. Well, that is probably a debate and a contest that won’t arrive until the very end of this year; and more likely, 2022.

Deflation in the price of batteries, not in the price of oil, will be a primary driver of the global economy this decade. And before we reach the year 2030 it may become routine for battery prices to be displayed, like a daily ticker, in financial media. Between then and now, much can evolve in the battery industry. Perhaps a vertically integrated model like Tesla’s will prove optimal. Or, perhaps standalone battery producers aligned to specific automakers will become more common. What we know is that the learning curve is robust, and traditional lithium-ion continues to break barriers. BNEF reported in December that China has now broken the $100/kWh level, specifically in the EV bus market. And unsurprisingly, Tesla is reported to be eyeing the rollout of an EV that would break current sticker-price barriers with a $25,000 offering—in China. While that offering is not likely to appear soon, we know that EV priced in that range is a common, industry goal.

With Democrats set to control the legislative and executive branches, it’s no longer necessary to provide a continuous outlook for economic recovery. Moody’s is forecasting that the Biden Administration will provide an extra $1.9 trillion in fiscal support, and the Democratic agenda has been telegraphed for a long while. The executive branch will become immediately aggressive on the health care policy front, with vaccine distribution and ongoing pandemic management that conforms to 21st century standards. States and cities will get the fiscal support they need, so that everything from New York City’s transit authority to the California public school system can rebound. There will be extended unemployment benefits; more stimulus payments to citizens; and various forms of debt and rent forgiveness. Small business, a keen focus of both political parties, will also get further support. (Just to offer some anecdotal evidence, I know several business owners here in Portland who used small business support to keep people employed and shore up finances, as logistics and payments became uneven in their supply chains and customer accounts. Accordingly, these businesses will be quite ready-to-go as 2021 proceeds). Put another way, I thought Paul Krugman was wrong, timing wise, when he asserted last year that the rebound could come quickly, like the aftermath of an interest rate shock. Now, it seems that type of rebound is more achievable, but for reasons no one (including Krugman) had anticipated: fast rollout of vaccines. Finally, it’s important to understand that in extreme contrast to the Great Recession ten years ago, US household balance sheets are in good shape. Americans are paying down debt, and direct payments have helped enormously. While the recovery will still take two years to play out, the technical end of the recession probably occurred last year. And, even if the US entered a new downdraft recently—something which economist Justin Wolfers thinks is possible—that too will end shortly.

A climate-focused infrastructure investment bill will probably come later this Spring, after Democrats have addressed voting rights, and the pandemic. We can make reasonable guesses as to the contours of such a plan. First, the Department of Transportation will swing heavily away from highways and vehicles, to concentrate on public transit. EPA will fire up the regulatory apparatus and press the lever to accelerate further closures of coal plants and disincentives for new gas-fired power plants. We may even get the first lite-footprint of a carbon tax, but one at the token-level that creates a path for something more robust in the future. Biden himself has already touted trains and charging stations as top priorities, and frankly those are very easy policy goals to lay out and achieve. All the normal course emissions goals for cars will be put back in place, and we may even see an increase in the gas tax. Finally, I would expect that a number of flagship infrastructure projects that have been waiting in the wings for years will get a green light. A new tunnel between Manhattan and New Jersey comes to mind. As does a proper re-ordering of passenger and freight rail in many regions, but especially in Chicago. Urban areas that have already undertaken local tax increases to fund metro buildouts, like Los Angeles, will probably get completion funding to simply bring current projects to faster delivery. Just to remind, the US remains in a multi-decade infrastructure deficit. The US economy could enjoy, therefore, a sustained ten year boom simply on the back of addressing that long overdue investment need. When you put such plans together with a global economic recovery, it is not unthinkable that the US could put together a year or two of 4.00% GDP growth—a level last achieved twenty years ago.

The market cap of TAN, the Invesco Solar ETF, rose to over $4.5 billion—more than a tripling since the end of August. The advance is partly explained by the share price increase, but also steady fund inflows. According to Invesco’s most recent report, assets reached $1.335 billion on 31 August 2020 when the share price reached $56.74. At Friday’s close on 8 January 2021, when the share price reached $119.13, the ETF’s asset value stood at $4.956 billion. While this ETF was already advancing strongly in recent months, the Georgia senate result unsurprisingly sent its price from $106 to $120. That’s probably an overreaction, but it illustrates the opportunity and risk as global capital surges towards such investments.

A closer examination of the components underlying the ETF, however, suggests that the fortunes of global solar are not exactly dependent on US policy. Much of the developing world, led by China, is embracing and adopting solar so quickly now that one might call it a capitulation. So the share price response to US senate elections is more behavioral. Yes, if the US adopts solar more aggressively, that will add to the earnings momentum of the global solar industry. The companies that are making the biggest advances inside the ETF are names like Solar Edge and Enphase of course, but especially the Asian located companies like Daqo New Energy and Xinyi Solar Holdings. One risk is that global capital needs to gain exposure to wind, solar, and EV at a rate and at a level that currently well exceeds the supply of such shares. Should this happen, or if it’s happening already, then the share prices of solar companies will way overshoot their actual growth rate, and that could lead to very painful corrections. Looked at another way, this is perhaps unavoidable.

Accordingly, it does seem likely that growth momentum—real, actual, fast adoption of global wind, solar, battery storage, and EV—is going to be the backdrop that attracts smart money, dumb money, and every other kind of money in between to these sectors. Investors will need to manage their risk carefully, because gains could be rapid and steep. But overall, these are wonderful problems to have. As I mentioned in previous letters, the capitalists are coming to climate action, bringing their dollars. And there’s nothing to complain about in that, even if a large bubble forms. After all, investment bubbles are an imperfect, but highly effective way to get new technology distributed. One just has to develop a framework, however, as to when the music may stop.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.