Oil at Bay

Monday 20 April 2020

Global oil demand took three years to recover from the great recession by reaching 4201.9 Mtoe in 2010, eclipsing the peak of 4163.9 Mtoe set in 2007. The question of whether demand performs similarly after this crisis has everything to do with the macroeconomic duration of the recovery, and, whether adoption of new technology will have the time required to head off a petroleum resurrection. Keeping oil at bay will require that electrification of transport, which has now established a solid basis for further growth in China and Europe, sees a similar tipping point in the United States. Would three years be sufficient for that tipping point to unfold, in the US? Tweak the slider bar of the recovery’s duration, while also turning the knobs of policy and affordability, and outcomes from the US begin to change. Regardless, because the US represents such a crucial piece of the oil market, it’s now determinative to the trajectory currently in motion in China and Europe. Given our backdrop, that the internal combustion engine has seen its apex in two of three of the world’s largest regions, how best to think about the next move from America?

Well, I believe many analysts will waste valuable time postulating theories about behavior change. I’m not so big, on behavior change. The pandemic, it is already claimed, will give birth to radically new preferences in how much space cities give over to cars, how much air travel business travelers demand, and a broad embrace of everything local—indeed, a veritable renaissance of localism. These are the conditions society has been forced into today—so why not just project these behaviors out to the future, converting them to discretionary choices made collectively? Here’s why: for oil demand to reset at a lower level, and then to begin a sustainable decline, will require new infrastructure to support new choices. Transport electrification must become both the policy choice, and soon enough, the economic choice of both public and private sector purchasing decisions. Without such an outcome, society will simply get back behind the wheel of the existing fleet of buses, trucks, and cars—driving them along existing networks.

So stubborn is the American topography in this regard, that vehicle electrification will have to be additionally supported by a resurrection of public transport. What would be required, in even the most cursory glance? Rebuilding the Boston and Washington D.C. metro systems for starters, and then expanding them; giving large sums of funding to myriad other US cities already building out transit networks, who will soon be halted in the face of further financing constraints; and, building high speed rail in dense corridors—East coast first, then West coast. Other key cities east of the Mississippi, from Detroit to Chicago, St. Louis, Nashville, and Atlanta would also need to be included in such a network. If you want to take a bite out of every section of US oil demand, you will need policy incentives that address every segment from short-trip commutes of 5-15 miles to the mid-range air travel itineraries of 1-3 hours. Experientially, that looks something like the following: workers from Boston to Miami rarely take the car to work, or take a plane to another East coast city for a business trip. In other words, the East Coast finally realizes its infrastructure fate, long forestalled: looking, and very much operating like Europe.

Is oil demand in decline in Europe? Indeed it is. At 648.8 Mtoe in 2018 (and roughly the same in 2019), EU oil demand sits 11.6% below the 2007 high of 734.5 Mtoe. But notice this is not exactly a rapid decline, about 1.00% per year. That’s why I warn, and will continue to warn against optimism about a peak in global oil demand. Oh yes, we may indeed get our peak. We may indeed be able plant a flag in 2019, as the year King Oil finally stopped growing. But that peak may be hollow, from a climate perspective, if it converts to a lengthy plateau.

Unless the United States rapidly lifts market share of EV from the current 2% to above 5%, and invests in public transit, the very good transport electrification taking place in China and Europe will not be enough to sustainably prevent a global oil demand recovery, because Asia ex-China, Africa, along with the US will dampen the effects of any pull lower on demand elsewhere. Alternately, one could project a much longer macroeconomic recovery, with global oil demand on a course to slowly and painfully recover along with global trade and GDP, thus allowing time itself to produce desired outcomes from energy transition. That too may happen. But if you are assigning the responsibility of transition to time, then one must also assume all the stubborn effects of slow growth too. And slow growth periods, despite the helpfully low interest rates which tend to arise within them, are equally friendly to path dependency, and the tendency of the economy to rely on existing fleets of everything, from cars to power plants.

Slightly more than half the world had already reached peak oil demand by 2018. But that did not prevent global oil demand from growing both in 2018, and 2019—albeit more slowly. The chart below was first introduced in Oil Fall; and when I talk about these effects to audiences, I use the following analogy: imagine instead of oil consumption we are instead tracking junk food consumption among children. Getting half the population of children to halt their junk food consumption growth will certainly drag the total growth rate down. But you are still a long way from junk food declines if the other half is still increasing its intake of Nacho Cheese Doritos, Mars Bars, and Mountain Dew. And there are always more people. Because junk food populations, just like oil populations, also continue to grow.

These efforts are further complicated by rebound effects. In post peak regions, lower prices don’t spur new demand as much as one might theorize. Indeed, after the great recession, oil demand in the OECD very clearly rebounded with job growth, not price. But in the developing world, exceedingly low prices open up gateways for new adoption. Yet another reason to be concerned if one is positing a long recovery phase in which oil prices remain exceedingly low. Let’s be clear: the risk is not that such an ultra-low price domain would send oil demand to new all time highs. Rather, that a long duration regime of very low oil prices could nurture conditions in which new rounds of oil adoption occur, thus helping to build that most frustrating of outcomes: a long plateau of oil demand.

When the Oil Fall supplement is released in May, I will update the above chart with the best data available. But it bears repeating a key forecast in Oil Fall: the end of oil demand growth could produce the worst of both worlds, one in which the oil industry is decimated by enormous job loss and capital destruction, but also with little near-term prospect that global oil demand enters outright decline. This between-state is often ignored in people’s eagerness to realize clearly defined outcomes. Humans are either/or thinkers by design, to our detriment. But more often than not, we are called upon to grapple with mixed conditions that don’t give way to any clear direction.

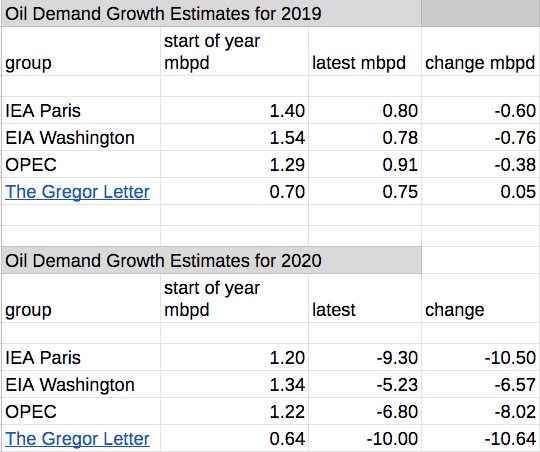

Both OPEC and the IEA in Paris last week released their updated estimates for 2020 oil demand. The revisions are unsurprisingly massive. (To be honest, though, it appears OPEC is kind of pulling its punch). Conversely, I was encouraged to see the IEA—normally over-conservative and reluctant to back down from a previously bad forecast—absolutely kick the furniture over with a declaration of major decline. (N.B. - In that table, I have changed the unit of account in the 4th column from a percentage change, which was suboptimally illustrative given the enormity of the revisions, to a simple change in barrels.)

To pick up the strands from the previous discussion: you can imagine that many analysts are integrating these shocking demand declines of 5, or 6, or even 10 million barrels per day into their recovery forecasts. If you quickly glance and don’t think too hard, it may seem obvious the world will never rebuild that much demand until years of time eventually pass. I hope that’s true. But I would remind just for argument’s sake that if a vaccine were released this year (and no, that is not going to happen) that the existing vehicle fleet is very much with us, parked and waiting. What’s not at our disposal, what’s not in our possession, is the capital required in the private sector to more rapidly change out the existing vehicle fleet. One of the more confounding aspects of recession, and tech adoption.

Note to readers: you will have noticed I’m hammering away at both sides of the oil demand recovery issue; in one letter laying out all the reasons why oil’s future is toast, and in another letter warning that demand recoveries cannot be dismissed. This is intentional. I want to very much emphasize the unique nature of a pandemic—arriving at a time of energy transition—as a moment of extreme uncertainty. And most important, to keep in the forefront of your mind that a collapse of both the oil price, and the oil industry, do not and should not be read as a signal that global oil demand is fated to collapse sustainably. Oil dependency is a real thing, and the past 200 years of fossil fuel consumption have shown repeatedly, several times with coal and oil also, that resurrections of demand are persistent and frequent.

The competing forces of austerity, and public investment in the form of infrastructure spending, will very much guide our path over the next two years. As most will recall, support packages launched from 2008-2010 in China, Europe, and the US largely gave way to belt-tightening, or tighter money impulses once the shock phase of the great recession was over. This created a sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and a near-double-dip recession in the US in 2011. You should therefore closely follow the conversation in Europe, largely controlled by Germany, about the prospect of both eurobonds and a green new deal to build clean infrastructure.

As you may know, a mutualisation of debt or the creation of a common eurobond has been a line in the sand for tight-money policymaking circles in Austria, Germany, Finland, and the Netherlands. For example, see this week’s piece in the Economist, The Dutch Grumble over Europe’s Coronavirus Cheque, and also this Irish Times piece, Government Supports Green Deal Being Central to EU Economic Recovery Plan. Generally speaking, the EU seems rather open to green infrastructure spending but is bogged down in a debate about mechanics over its financing. If one forecasts however that the tight-money member states are on course to endure a long duration recession, then pain itself may eventually take over and break any logjam in the policy dispute.

An alphabet soup of letter-based descriptives currently dominates the macrosphere, from V, to W, to L shaped recoveries. So it may be of some interest that over at FX Weekly from Nordea Bank, they’ve produced an early look at the “L” shaped recovery currently coming into view in China. For our purposes, the level to which coal consumption has recovered is poignant, because it reflects both utility and industrial components: electricity as a basic necessity likely accounts for the bulk of the “L” progress, back to an index level near 75. But, depressed industrial activity will likely pin consumption there for a while, well below where the year began. One observation, spotted elsewhere and that I’ll repeat here, is the view that a best case outcome to our predicament is a severe recession that lasts about 4 quarters. In other words, should we experience an “L” style recovery we might feel thankful.

We are just 7 months away from US elections, and the President’s approval numbers are crumbling. Pollsters will tell you that a crisis in its early phase tends to boost sympathetic support for incumbents, and we’ve seen that so far across the world. But the effects can be ephemeral. As the storyline has emerged of the US administration’s broad and lasting incompetence, the numbers have turned down. The latest Gallup poll has the President’s approval now declining swiftly from 49 to 43, which may very well qualify as a breakdown of his long enduring support, from already low levels. A separate Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll found that Joe Biden has a 7 point lead with likely voters in November, and a majority, 51%, now disapprove of the President’s handling of the pandemic. 60% of Americans are worried that restrictions could be lifted too quickly.

Not that this is news, but in addition to the shape of the pandemic, and also the momentum of energy transition, the outcome of the November elections must also now drive analysis of likely macroeconomic outcomes. The incumbent President losing the election is now the base case, and you don’t need to know the details of that case beyond the fact we will certainly be in recession for the balance of the year. It may seem bizarre that the US stock market for example is up at current levels, but 7 months is not too far for the market to start pricing in significant policy changes. As a sign of the current impulses coursing through US culture, this brief essay by Marc Andreessen is a clarion call for America to start building things again, for example. If that’s a reliable signal, and I think it is, the electorate is now quite likely to vote against the traditional austerity party, the Republicans.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

Photos: 1. Arriving Seattle Airport, with Amazon Prime aircraft in distance, March 2020, Gregor Macdonald. 2. Tilikum Crossing Bridge, for bikes, pedestrians, and transit only, January 2018, Portland, Oregon, Gregor Macdonald.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.