Oil Dependent

Monday 4 April 2022

Despite a long term preference for supply side solutions, the United States once again faces the consequences of having done so little to lower its demand for oil. The titanic advance in US energy production from all sources has paid out handsome dividends to the US over the past decade. The country produces so much natural gas now that it can export at least 10% and sometimes as much as 15% of its supply. And, from a low near five million barrels a day, the US now presses up against 12 mbpd of oil production. This is in addition to over five million barrels a day of natural gas liquids production. All these fossil volumes translate directly into the country’s muscular refining capacity, which has entirely tipped the terms of trade and put its petroleum balance sheet into small, occasional surplus. Meanwhile, US wind and solar now account for more than 10% of the country’s electricity supply. This fast growing inventory of clean power will not only fund EV demand, but will also free up even more natural gas and coal for export. The US is now a global energy giant.

But the one superpower the US continues to ignore is voluntary control of its own demand. Yes, over the past 20 years, US transit ridership has risen, fuel efficiency of vehicles has improved, and the country has managed to restrain its oil consumption to an oscillating plateau. In one sense, it’s a true victory that US oil use peaked 17 years ago, in 2005, at 40.2 quadrillion BTU. But comparatively, no western nation has done so little to actually force its consumption into decline.

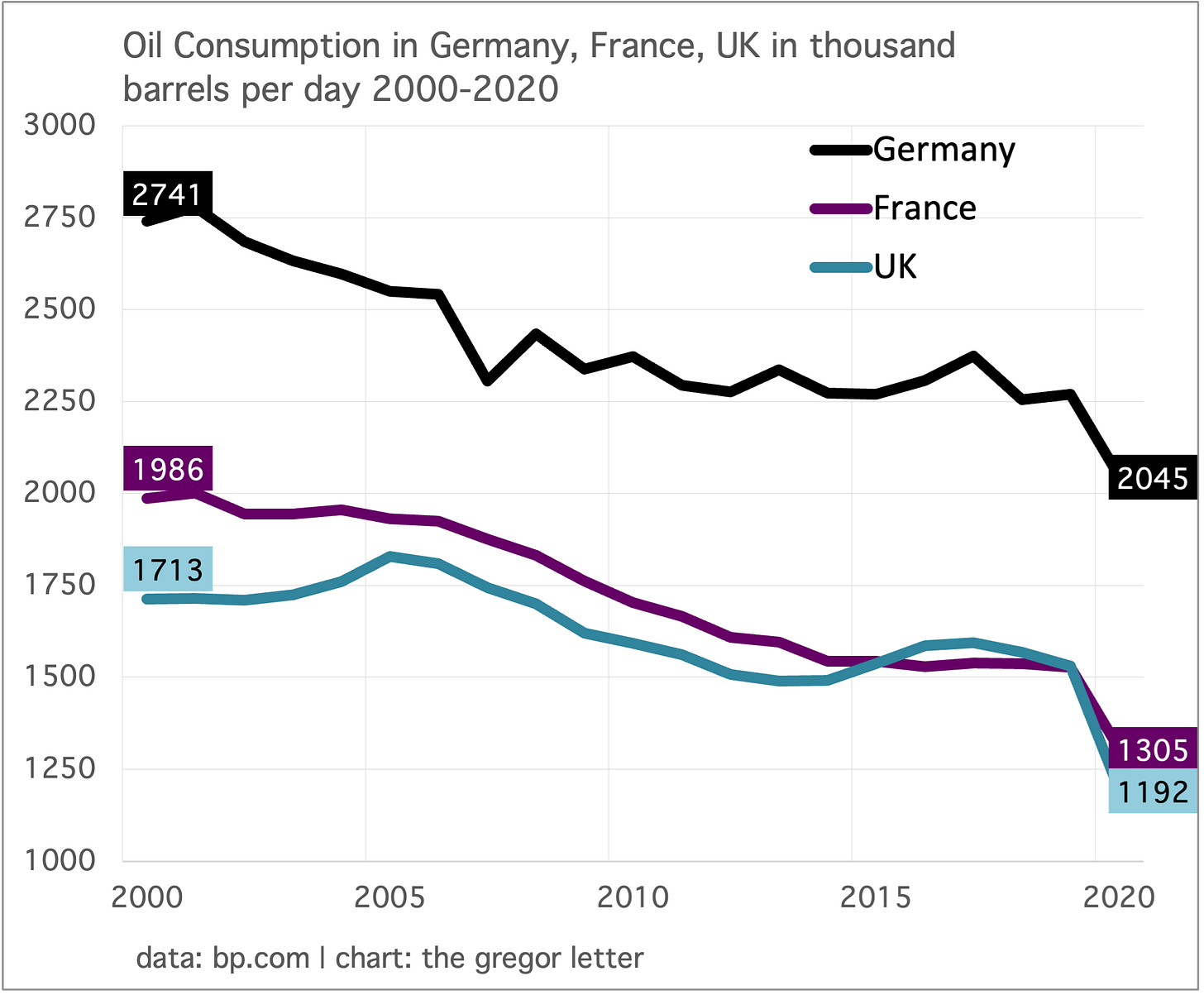

The problem of course centers on the structural and political supremacy of cars, and car ownership. Here, the cultural agreement about the protection of cars is truly bipartisan—a third rail of American politics that no elected politician dares to touch. That’s why the national petrol tax has not been raised in 29 years, why tolling—which was pretty commonly introduced in the 20th century—has seen no growth, and why not a single US city dares to even broach common solutions like congestion charges. In its totality, US vehicle ownership is massively subsidized through road and highway expenditures, and only the lightest registration fees. And while individual US states have made some moderate steps to increase their own petrol taxes, disincentives to overall consumption of petrol remains light. Petrol in the UK for example typically costs 40-50% more than in the US, and the UK has results to show for it: the country’s consumption is down 11% since the year 2000 through the year 2019 (the last useful data year, given the pandemic year of 2020 is an outlier.)

But perhaps the most ridiculous phase of American capitulation to the hegemony of petrol appeared recently, when Democratic leaders of US states and cities—many of whom profess a committed policy position on fighting climate change—announced multi-billion dollar rollbacks of petrol taxes. The most egregious proposals are coming from California, which could send $9 billion directly to vehicle owners to offset increased petrol prices, in addition to a relaxation of existing petrol taxes. These are the kinds of sums that were once attached to segments of California’s high speed rail plans. While the package includes a token subsidy for existing public transport—by making it free for three months—the overall portrait is lurid: The Democratic Governor of a deep blue and Democratic state, that has so far avoided any imposition on its own oil consumption outside of EV adoption, now subsidizing oil consumption.

It’s long been observed that in American culture freedom itself is intertwined with car ownership, and the perceived natural right to cheap petrol. But the US, despite cleaning up its petroleum balance sheet in terms of trade, is far from being a surplus oil producer like Russia, Saudi Arabia, or other OPEC states that can subsidize local petrol prices. Thus, a kind of tediously repetitive cycle comes back around every few years, in which voters get mad at politicians as their own, individual dependency is revealed all over again. Sadly, it just never occurs to the US that a very different kind of freedom can be found in lowering one’s dependency on oil. That used to be an idea with broad support, way back in the aftermath of the OPEC oil shock of the 1970’s. Perhaps just enough time has passed, however, to have forgotten those lessons.

OPEC held back this month on any 2021 downward revisions to global oil demand, as it awaits further data. Accordingly, we remain with the 1 mbpd cut from IEA (to the original 2021 growth forecast) and the 3 mbpd cut from The Gregor Letter as laid out in the past several issues. Let’s post the combined IEA and EIA chart again:

On the supply side, however, the picture is far more complicated. First, we have a new inventory release program announced from the US, as the Biden administration plans to empty the strategic petroleum reserve by 1 mbpd. Leaving aside the wisdom (or error) of such a tactic, at least they figured out how to do it. Single-shots of oil inventory releases don’t work: the futures market quickly absorbs them. But a more chronic release of a million barrels a day really does have a dampening effect on price. Oil finished the week down substantially. But alas, you see the problem: both the federal and state governments in the US are doing everything they can to make petrol cheaper, at a time when the best course of action is to reduce demand.

The global supply picture is further complicated by the repressive effect that sanctions have on the flow of Russian oil exports, and on actual Russian oil production. The former is not sanctioned outright, but some of the normal export channels run through buyers that are simply queasy about entering into those shipping contracts. Accordingly, countries like India and China have taken up some of this oil. Russian domestic production meanwhile can be expected to deteriorate, as technical and joint-venture influence from the West withdraws. It’s almost impossible to forecast how this plays out. But we do know one thing: erosion of Russian production will worsen, as supply chains of equipment and expertise dry up permanently. A recent round-up from Reuters suggested, for example, that the net of all these effects could see Russian supply drop by 3 mbpd starting this month. That is 30% of Russian production.

Looking ahead, it’s possible to make a simple conjecture about this year’s supply and demand picture: even if global demand falls as far as The Gregor Letter forecast, it’s likely that supply will be at least as pressured to the downside, if not moreso. Thus, until the Russia-Ukraine war is resolved enough to lift sanctions on Russian supply, the world will witness falling demand and rising prices.

Understandable moral outrage is driving many to demand that the EU entirely cut itself off from Russian imports of oil, and gas—immediately. Unfortunately, this is not only unrealistic, but may be inadvisable. It’s notable that most of these voices do not possess expertise in the energy area. That’s not surprising, as even educated people can come to believe that energy demand is discretionary. This does not make the question less pressing, however. There are further actions both the EU, the US, and frankly the entire OECD can undertake to hurt Russia economically. One of the most powerful channels would be voluntary, collective action rather than top down sanctions. But just to be clear, when Lithuania announced it would immediately halt gas imports from Russia, it was not and is not correct to say, “If Lithuania can do it, so can the entire EU.”

Back in the land of realism, however, most global energy experts have understandably centered on phase-out plans. These plans are excellent, and offer much of the immediacy more passionate voices desire: they send strong market signals that future demand for Russian energy will decline. The IEA of course offered its 10 point plan just weeks ago. Now comes E3G of London with a plan to unhook the continent entirely from Russian gas by the year 2025.

One mistake the West seems inching towards is a kind of self-harm, in economic terms, as a way to punish and thwart Russia. So far, most of the damage done to Russia has been through its own inept and failed strategy in Ukraine. Europe and the US need to be careful about putting their economies into recession, because that would in turn lower the public tolerance for any further policy actions against Russia. In truth, direct military action by the West against Russia, inside of Ukraine of course, would be more efficient at this point. Reports from inside Russia, meanwhile, indicate the public is telling itself that they only need to endure about three months of hardship, and then all will be back to normal. Given the hard evidence now coming through of atrocities and war crimes, that timeline to normalcy is simply never going to materialize.

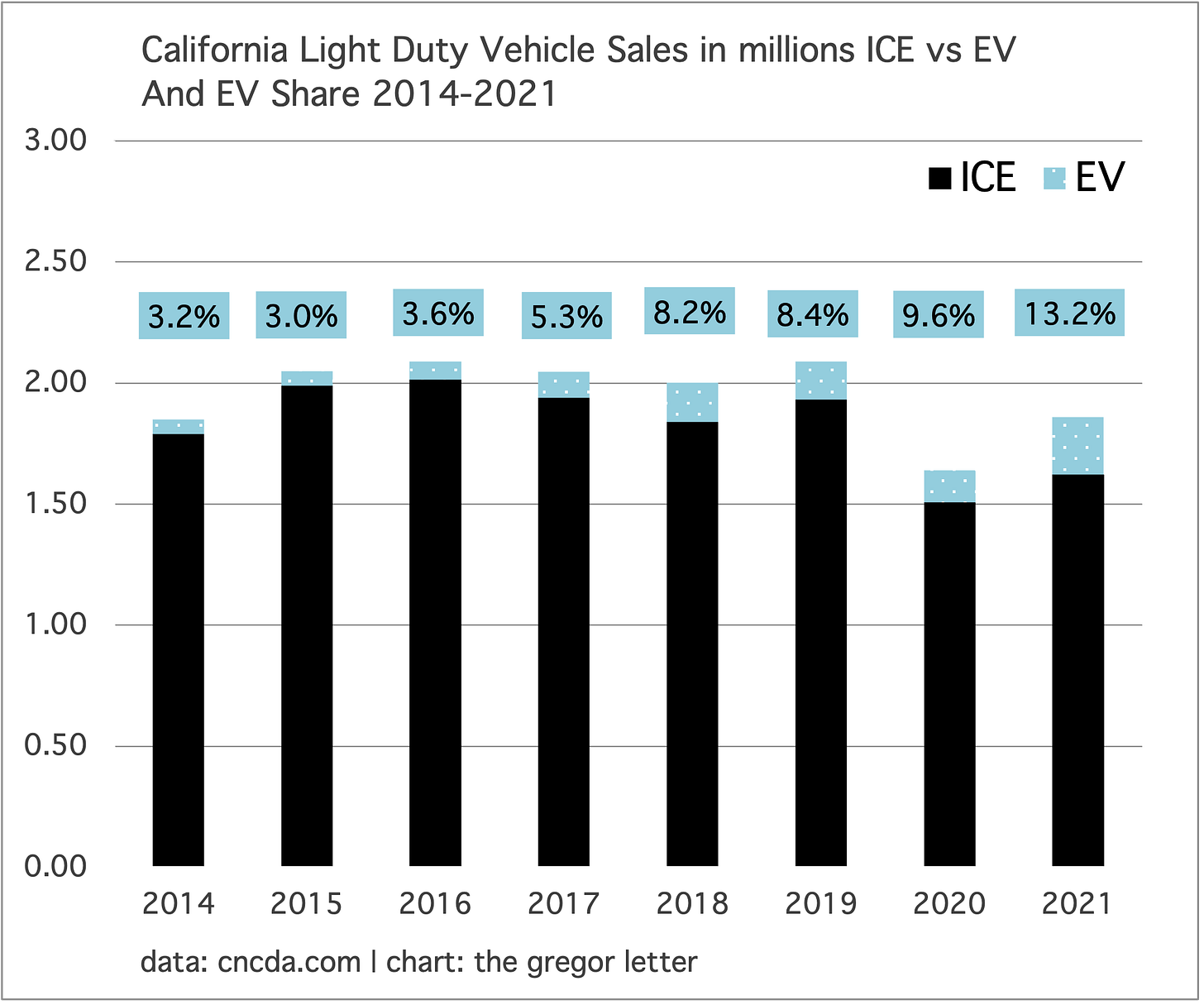

Petrol consumption has not only peaked but has entered decline in the world’s fifth largest economy. While national petrol consumption has rebounded in the US nearly to its long term flatline, California’s petrol consumption has clearly entered decline. Work-from-home options, very high rates of EV adoption—and now a turn to net outward migration—have combined to put the state’s road fuel on a downward trajectory. The full year 2021 data on California’s gasoline consumption has now been released:

Part of the reason that California’s petrol demand is not rebounding is that adoption of EV has now gained very significant traction.

Readers may be familiar with adoption curve models but just to remind, a new product tends to enjoy significant sales acceleration after reaching 5% market share. EV in California hit that level in 2017, and are now zooming towards 15%. Given the new cloud hanging over ICE vehicles, we can pretty confidently say that it's now lights out for gasoline in California. ⛽

The US labor market is going from strength to strength as an important measure, the participation rate, is rapidly healing. Friday’s US jobs report showed another strong push forward in the aggregate as March saw 431,000 jobs created. The composition of those jobs was also encouraging, with a strong advance in service jobs. Something to consider when you review the list below: cafe and restaurant jobs actually represent an important segment of urban life in America, indicating both a return of demand, and a return of available workers. This particular ecosystem accounts for a whole range of jobs from specialty farms to delivery services, equipment sales, and commercial real estate. The pandemic killed this ecosystem, and is the primary reason why so many neighborhoods in urban America have mostly gone silent for the past few years. And one more point: wages earned in this sector have traditionally funded aspiring artists. So it’s great to see this bouncing back, and it promises a fuller return to normalcy this summer.

But the most important reading from the jobs report was found in the participation rate. This measure lagged greatly coming out of the pandemic lows of 2020. And, it greatly concerned economists because it was not going to be possible to fully heal supply chains or relax inflationary pressure unless the economy restored the efficient throughput required. Well, prime age participation is now back to within a percentage point of its previous level. While concerns about the future of the economy are quite legitimate right now, the US labor market is simply too strong to start pricing in a recession. Yet.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.