The head of the International Energy Agency declared in the Financial Times that all fossil fuel consumption will peak this decade. This would have been a big news item five years ago, but just about everyone is prospecting for peaks these days. The Gregor Letter for example downgraded oil coverage some time ago—while still keeping tabs on global consumption—and the focus here has moved on to the far more important question: how much longer do we have to wait before decarbonization finally delivers emissions declines. The current answer on that uncertainty is not so promising, unfortunately.

The IEA head, Fatih Birol, has a tendency to use imprecise language when talking about the tricky categories of growth, peak, and decline, and his piece in the Financial Times was no different. In the lede, he cites decline rhetorically, dangling that outcome as unappetizing to the coal, natural gas, and oil industries, but an inevitability nevertheless. Well of course. But then the article, further down, admits that the declines, when they come, will themselves not be linear. That sounds like a mild acknowledgment of reality in post-peak periods: rough and lengthy plateaus that don’t convert easily to declines. As always, intuitions assume declines follow imminently after peak. But at the scale of the global energy system, that is simply untrue. Let’s be clear: peaks rolling over quickly into declines are not observed. Overall, Birol’s FT piece follows this intuition, and that is either an error of analysis, or of writing, or both. While it’s true that achieving peak is a necessary goal, it is not sufficient to solve the problem. And that reality becomes more acute, actually, as we now approach peak consumption of the main fossil fuels. Hunting for peak five years ago, when it seemed impossible, was a worthy game. But peak is no longer the play.

Meanwhile in the US, the EIA is now forecasting that gasoline consumption is headed for mild decline. Wonderful. It only took twenty years from peak. According to the latest STEO report:

We reduced our U.S. gasoline consumption forecast because the U.S. Census Bureau revised its population estimates for the United States to include fewer people of working age and more people of retirement age, who tend to drive less. The revised population estimates have also resulted in a downward revision of our vehicle miles traveled (VMT) forecast, which directly affects motor gasoline consumption. We forecast U.S. gasoline consumption will average 8.9 million b/d in 2023 and 8.7 million b/d in 2024.

The Gregor Letter has previously taken the view that California gasoline consumption finally fell off its own plateau after twenty years also, and is now in decline. The natural next-step would be to see US gasoline consumption also fall into decline. But we’re too early in EV national adoption, and we have no national policies penalizing existing fuel consumption. In the chart below, notice how gasoline demand has been “peaking” for nearly twenty years also, on a national basis.

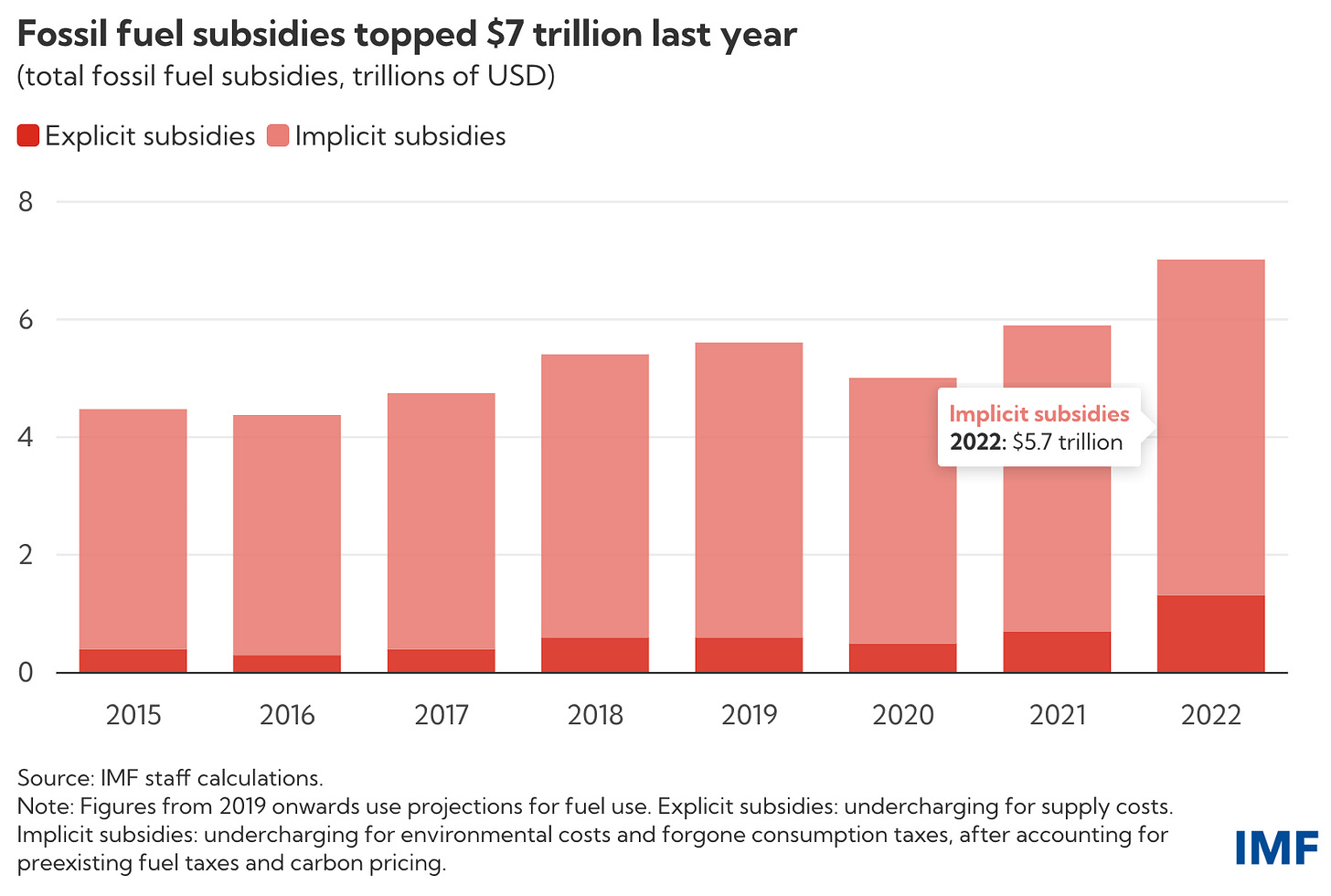

Quantifying indirect subsidies to global fossil fuel industries is absolutely the right analytical approach. To get the true picture of how path dependency is maintained within coal, natural gas, and oil systems, one has to focus not on subsidies to extraction, but subsidies to consumption. The IMF has done just that in their latest report. Let’s first take a look at the big picture:

Notice the huge spread between explicit and implicit subsidies. That’s another way of portraying the fact that the systems we subsidize to consume fossil fuels are far larger than the fossil fuel production system itself. The most obvious example: the transportation and travel sector, now the top sector for emissions in the US, and the second place sector for emissions globally.

The IMF fingers the problem correctly, noting that untaxed air pollution and untaxed emissions are the main source of indirect subsidies. They write in their report:

….undercharging for local air pollution and climate change accounts for about 60 percent of total fossil fuel subsidies in 2022, undercharging for broader externalities and supply costs another 35 percent, and the remainder undercharging for general consumption taxes.

What would a proper scheme look like, for road transportation? Imagine every city in Europe and the US adopting London’s road-charging scheme, which started out twenty years ago with fees on trips, but has subsequently expanded outward to apply fees based on the emissions that come from fuel and car types. If you meet the emissions requirements, no extra charge. If you don’t, well, pay up.

After maintaining a strongly negative stance for many years on wind and solar, perhaps it’s time for Bill Gates to admit he was wrong. The new Elon Musk biography by Walter Isaacson apparently contains a revealing quote from Gates, demonstrating he has not evolved even a little on this question. As reported by CNBC:

Gates argued that batteries would never be able to power large semitrucks and that solar energy would not be a major part of solving the climate problem. “I showed him the numbers,” Gates said. “It’s an area where I clearly knew something that he didn’t.”

Oof. If that sounds bad, it’s actually worse than all that. Since Gates took his stand against wind and solar’s ability to do much to solve climate change, the two technologies have stormed the gates of the city, so to speak. Ha. So Gates is even more wrong today than he was when he started voicing this view last decade. Look at these numbers:

Just thinking about loud, but perhaps wind and solar know something that Bill Gates doesn’t.

Remember, we are potentially on a path that will see combined wind+solar grow from nearly 12% global share of electricity in 2022, to 30% of global electricity by 2030. There is considerable uncertainty about reaching this share, given the uncertainties in total system growth by the end of the decade. But if you told someone in 2012 “I have two technologies that can scale fast, will drop steadily in cost, and will reach 12% of global power ten years from now but then really take off towards 2030” you would think that’s a breakthrough. But sadly, Bill Gates keeps flogging that word, breakthrough, implying as always that wind and solar are not enough and we need this other, unnamed thing—which Bill never reveals.

It’s great that Gates is working on small modular reactors. The Gregor Letter remains steadfast in its view that we must augment wind and solar (the undisupted leaders of decarbonization) with some nuclear. But letting the years pass without updating your views is a no-no. Big no-no. Suggested title for a Gates Notes post: “How I Was Wrong (Then Got Even Wronger) about Wind and Solar.” 🌞

The IEA has done some excellent research on the fuel consumption effects of Work From Home. One of the more fascinating points made in the IEA’s most recent Oil Market Report is that Work From Home broke the relationship between vehicle miles travelled (VMT) and GDP. This rather forcefully answers a long-standing question: is personal vehicle travel in post-industrial economies a key feature of GDP, or can OECD economies produce just as much GDP while driving less? As we learned during the pandemic, the long expansion of a digital labor meant that up until 2019, an increasing portion of the US workforce was driving to an office and simply logging on to the computer. No drive to the office was necessary. Here is the IEA on the WFH phenomenon in the US:

Since the pandemic, the previously consistent relationship between the US Federal Highways Administration (FHWA) vehicle miles travelled (VMT) data and GDP has changed, with fewer miles now being driven per dollar of output. This decline in intensity closely mirrors the estimated impact of WFH and on adjusted fuel usage. The VMT marks for 2021 and 2022 both fall short of the previous trend by close to the 5% implied by our analysis of EconPol’s study. Furthermore, the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) data show that for March and April 2023, the number of Americans staying at home each day increased by 9% compared with the same period in 2019. At the same time, the number of very short trips by any form of transport (less than one mile) increased by 24%, while the number of trips in some major medium and longer distance categories fell. These apparent behavioural changes imply substantially reduced car use for commuting and as well as for other everyday activities.

In the chart that IEA supplied with this analysis, it will come as no surprise that the US shows up as the most sensitive domain to WFH effects. Well, of course. The US is the global capital of car culture.

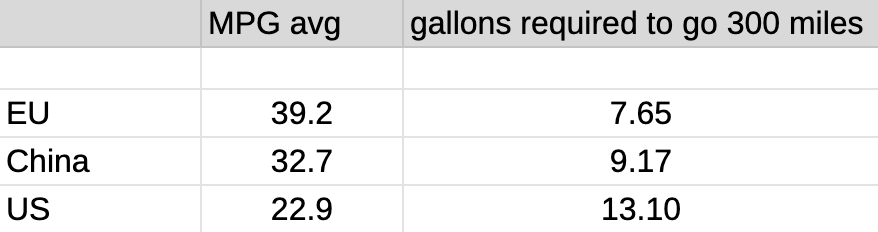

This is also on occasion to remind readers of a very important dynamic that is about to play out in the US: because we drive more, and especially because fuel efficiency in the US is poor (low) the sensitivity of national fuel consumption is higher to the adoption of EV. The February 20 issue of The Gregor Letter, Grunty Yank Tank, went into some detail on this imminent change, and provided a useful table:

As you can see, rapid EV adoption in a domain like the European union will not hit petrol demand as hard as in the US. The EU has for decades been curtailing petrol consumption through policy. The US only lightly so. Incredibly, it takes nearly twice the petrol to drive 300 miles in the US as it does in the EU. So every time the US displaces future petrol consumption through the sale of a new EV, the impacts are far more significant.

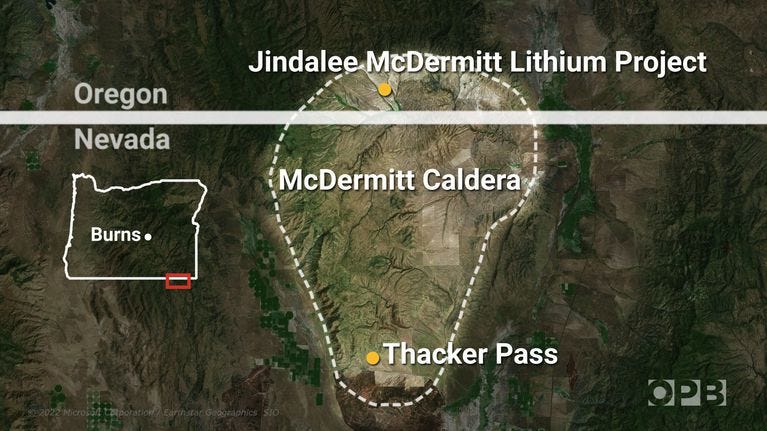

The tension between modern environmentalism and new resource extraction to fund the energy transition is going to intensify. It is indeed a curiosity that natural resource deposits are often found away from population centers, in low density regions, and often in deserts or other vast drylands. Historically, this has meant the very small populations which inhabit these regions have been victimized by state and corporate actors. This is enabled, in part, because lines are quickly drawn between those who want to preserve such lands in unspoiled condition, and those who want jobs in their development. Such is the case with the rolling discovery of lithium along the Nevada-Oregon border, in a region known as the McDermitt Caldera.

Note to readers outside the US: once you travel to the north of Nevada or California, you enter an active volcanic region that roughly begins with Mt Lassen in Calfiornia and runs up through the Cascades. Impressively, Fleet Street in London writes the best headlines and it’s hard to beat this one from The Daily Mail: World's biggest lithium reservoir found in supervolcano McDermitt Caldera in Nevada - with $1.5trillion worth of the precious metal that powers world's technology. And here’s a really helpful map from a local news organization, Oregon Public Radio:

As readers may know, we already have a BLM approved project at Thacker Pass, in the same region on the Nevada side of the border, which the court system has now cleared. So, the recent announcement, from a geologist’s point of view is not a surprise. The deposits are so substantial, that assuming economic recoverability, the US could be sitting on enough lithium to cover all forms of battery deployment for several decades. That is exciting. However, it will also mean a terrible desecration of those drylands, and that is something we will have to come to terms with, as a society. Something to keep in mind: we can run all the vehicles on half the energy. That is a hard fact that cannot be ignored. And it will bring with it a huge reduction in oil extraction.

—Gregor Macdonald