Portfolio Nuclear

Monday 26 June 2023

After decades of stagnation a notable uptick in global nuclear generation will occur over the next three years. And because of this advance—estimated by the IEA at over 300 TWh—the world’s electricity system is expected to meet nearly all marginal growth during this period with renewables: wind and solar clearly in the lead, and nuclear pulling up the rear. That would be a big accomplishment. Driving large energy systems towards a no-growth state for fossil fuels is not easy, but is a necessary first achievement before those same systems can tip, often years later, into fossil fuel decline. And if nuclear helps us get there, well, that’s a type of growth configuration that argues for a more modest pro-nuclear argument, one that’s better aligned with our current place in energy transition. In short, it’s way past time to rescue the nuclear question from the either/or trap, and to instead consider nuclear in a more junior, supportive role.

Absolutist arguments both for and against nuclear have been around for decades. But now that wind, solar, and batteries are the undisputed leaders of decarbonization, both arguments are now wrong. It’s not that nuclear technology changed. Rather, it’s that the world in which nuclear offers itself as a solution has changed. The absolutist positions have served a useful function however, as they’ve gathered like a magnet every last filament of insight to their respective views. With that clarity now in place, let’s consider the two extremes and recommend that both be abandoned.

The anti-nuclear argument is confident that no new nuclear should be built, ever, anywhere, and that devoting capital and human labor to new nuclear only serves to deprive necessary support for the real decarbonization leaders: wind and solar. This is plainly a zero-sum argument, and weak on its face. However, this type of analysis emerged over a decade ago before wind and solar had entered the steeper phase of their adoption curves, and it’s understandable why intuitions would lead to this view. In the same vein, the never-nuclear argument points out quite correctly that: 1. nuclear is far more costly than new wind, solar, or batteries. 2. nuclear’s construction timelines are so lengthy that we cannot bend emissions trajectories soon enough to head off climate tipping points. 3. nuclear waste storage remains an unsolved problem also, one with its own negative dynamics. 4. Private industry is not eager or even able to build nuclear without capital support and risk-sharing from governments, further complicating delivery timelines. 5. nuclear is burdened with a social-license problem that will always add to its high costs. 6. the learning rate never seems to improve with nuclear, unlike other technologies, and nuclear may even have a negative learning rate: relentlessly becoming more costly as time passes.

All of these arguments were competitive years ago, but degrade rather quickly when we step back from an all-or-nothing framing, and consider a much more modest buildout of new nuclear in a supportive role. In other words, once you place nuclear into a portfolio approach, where it would occupy, say, a steady 15% of expanding global power generation (compared to its current 10% share) it no longer matters that it’s slow to construct, more expensive, or harder to site. Asking nuclear to do less, while also building some, is the solution. Moreover, nuclear’s high and reliable capacity factor of 92-95% (the amount of up time for a nuclear plant on an annual basis) means that by adding a small amount of nuclear to wind and solar’s high speed buildout it becomes an amplifier: suppressing the opportunity for further natural gas growth by adding a booster to the large decarbonization project.

Just a comment: your correspondent once made these exact anti-nuclear arguments, because they were at one time more suitable to the context. We were far behind in decarbonization, and we needed to get going quickly—hence, high speed wind and solar. But just to say, the worst of these arguments now is the cost argument, especially when espoused by people legitimately concerned by climate change. Hey: climate change is everywhere and at all times going to be a destroyer of capital, infrastructure, agricultural output, generating property losses that stand to be cataclysmic. In that context, saying that nuclear costs too much rings hollow.

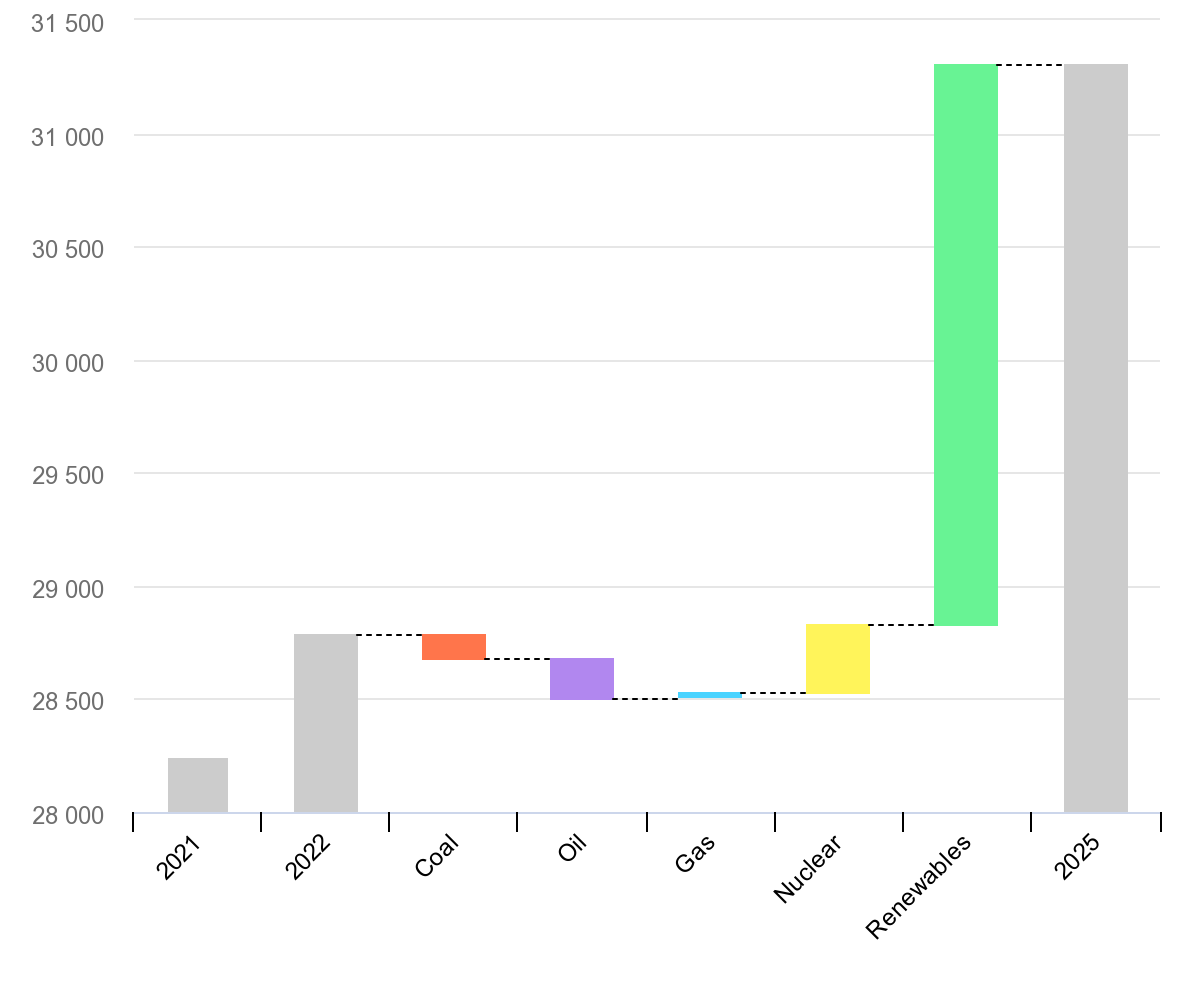

Before we get to the absolutist pro-nuclear argument, let’s take a look at the 2022-2025 forecast from the IEA in their 2023 Electricity Market Report. The chart is a bit unusual, but what it’s trying to show is that over this three year period, coal and oil in global power fall, natural gas makes tiny progress, and renewables, along with nuclear, handle (nearly) all the growth as the world’s demand for electricity moves from 28,733 TWh in 2022 to 31,295 TWh in 2025.

Why does this matter? Because, without that growth in nuclear generation, the gap in total demand growth would surely be filled by natural gas. The Gregor Letter addressed the natural gas problem over the course of three separate issues early this year, starting with this one, Bad Natty Emissions. Just to make this plain, those of us who rightfully cheer on the wind, solar, and battery buildout have been slow to admit that those technologies alone are still not covering all the marginal growth in global power generation. That problem too has been covered at The Gregor Letter, in Still Waiting, showing that even a very high growth case for wind and solar through the end of this decade may only be enough to cover marginal growth—without denting underlying fossil fuel dependency in power systems. We have equally been slow to acknowledge that natural gas adoption has been, and continues to be, ferocious globally and that this rapid buildout creates a new dependency for natural gas.

Here is the fundamental problem with the anti-nuclear argument in today’s context: saying we should not even build some new nuclear shirks the responsibility for an extended delay before fossil fuels actually decline in global power systems. It’s the view of The Gregor Letter that with nuclear in a supporting role, and starting now, we might plausibly get to fossil fuel declines in global power in 6-7 years. Without nuclear in a supportive role, declines in global power systems may not come for another decade or more. Here’s a big reason why: growth in total global electricity demand is already heady because a central project of energy transition is to move as much demand off liquid fossil fuels over to the powergrid!

Now let’s consider the absolutist pro-nuclear argument. Remember, this argument arose at least fifteen years ago, when it was not clear at all that wind and solar would cross the cost thresholds necessary to make them scale. Today, the argument has been obviated. One way to sum up this view: It’s just math, ok? Right, of course. Just do the math! But relevant math is often absent from nuclear absolutist presentations. This 2019 Wall Street Journal Op-Ed is a good example, see: Only Nuclear Energy Can Save the Planet - Do the math on replacing fossil fuels: To move fast enough, the world needs to build lots of reactors. The slight-of-hand the authors use here is to cite the large numbers associated with the end state of energy transition, not how we proceed there over decades. Worse, instead of acknowledging nuclear’s negative learning rate, or its slower completion timelines, the authors claim nuclear is the fastest way to decarbonize. Finally, (out) dating themselves, instead of admitting to the rapid growth of wind and solar, the authors default to a view more justified fifteen years ago: Solar and wind power alone can’t scale up fast enough to generate the vast amounts of electricity that will be needed by midcentury, especially as we convert car engines and the like from fossil fuels to carbon-free energy sources.

Let’s get real, and put an end to the scaling critique:

2895: total EU electricity generation in TWh in 2021.

2895: total global electricity generation in TWh in 2021, exclusively from wind and solar.

If combined wind and solar globally are already producing a volume of electricity equal to total EU consumption, well guess what, that proves wind and solar do not have a scaling problem. Just so that readers are better oriented to our current position, here is a chart showing global nuclear generation against combined wind and solar generation since the year 2000. Again, which technology is being criticized for not being able to grow quickly enough? Sorry, which technology is claimed to be the fastest? Request: please stop making the absolutist nuclear argument. It’s not realistic, and if your goal in making that case is to sound smart, well, it no longer sounds that way.

Over the next three years, as Vogtle in the US comes online, and as French and Japanese reactors start up again, and as new nuclear in China comes online, we are going to have a chance to stand back and marvel at a new reality: lightning fast deployment of wind and solar, with nuclear in a subordinate, junior role is one helluva powerful combination! While The Gregor Letter likes to avoid sports analogies, please allow just one: power hitters derive their run productivity in part from the skillset of other batters who cleverly do whatever’s required just to get singles and doubles. Big Papi swings and wins the game in the bottom of the 9th because there are runners already on base. Wind and solar and batteries are now the power hitters of grid decarbonization and everyone needs to capitulate and accept they are the undisputed leaders. But nuclear is how the power hitters can increase their runs-batted-in. Those extra runs are the difference now between taking full control of all marginal growth from renewables+nuclear, or, continuing to cede ground to natural gas. Your choice.

Challenges:

If you still believe it’s not necessary to build even some new nuclear, then show your work claiming the year emissions from the global power system go into decline. Not when emissions enter a plateau, no. We are near to that juncture already. You’ve got to show that wind, solar, and batteries are not only able to handle 100% of marginal growth, but are actually able to cut into that thick, sedimentary layer of fossil fuels in global power and get them into sustainable decline.

If you still believe we can only decarbonize with nuclear in the lead, you’ve got some ‘splainin to do. How are you going to transform the social-license problem in which most populations do not want new nuclear nearby? When is nuclear going to have a positive learning rate? If you’re going to blame bad policies for the fact that combined wind and solar have already trounced nuclear in the growth race, please explain what policies are politically workable to reverse the situation. Here’s a gimme: you don’t even need to address the rather gnarly problem of nuclear waste. Just make the case that nuclear is faster, and should be trusted to lead us now, with wind and solar switching places into the junior role.

Further thoughts on the portfolio approach, from a timely news story: Harry Markowitz, Nobel-Winning Pioneer of Modern Portfolio Theory, Dies at 95.

You are reading a free post from The Gregor Letter. There are very few of these, throughout the year. Why not become a subscriber? All paid subscribers get a free copy of the Oil Fall update package, and subscription rates are a very reasonable $80 per year, or $8.00 per month. Go ahead. Buy a ticket to the show.

The State of California has now updated Q1 2023 petrol consumption data and the decline continues. The Gregor Letter first keyed into the likelihood of this decline late last year. But declines are hard to come by, and are often preceded by lengthy plateaus. In the most recent issue, a laundry list of tipping points was identified, explaining how California finally got off its two-decade plateau. While this is a signal to US national petrol consumption coming off its own plateau, we are not far enough along yet with EV adoption, efficiency, and tax incentives/disincentives to see that realized.

Fissures in Russia’s military over the weekend raised the prospect that the world could have an oil supply problem if the country were to devolve into a period of instability. Fortunately, one of the most enduring and important governors in the oil futures market is the level of OPEC spare capacity. For example, OPEC keeps announcing plans to cut supply of late but the price of oil remains weak. Reason: the futures market just moves those barrels over to the spare capacity column. Accordingly, OPEC spare capacity has emerged from the pandemic period at unusually high levels, around 4 mbpd. If Russia did suffer a horrific civil war, that OPEC spare capacity would certainly not be enough to calm prices. But, it’s going to take meaningful disruption the oil market believes will endure to counteract that big, safe cushion of capacity on which OPEC now squats.

Grid monitoring dashboards are hot right now, as new players jump into the game giving us all real time feeds of daily power. Veteran grid geeks have long hopped on to the California ISO operator, whose good looking graphics give you a kind of air-traffic-controller view of the grid as solar powers into the afternoon, and then batteries come on in the evening. A new player on the scene is GridStatus.io and their displays are even prettier. Here is California’s grid at 20:35 Pacific time (the Sunday night before The Gregor Letter publishes). Fun: batteries are at the same level as nuclear. By the way, how great is it that California still has some nuclear!

The nice design at GridStatus.io is further enhanced by their integration of multiple grid regions. For example, blistering high heat is probably going to be a story in Texas for a while yet, so yes, you can just hop over there and toggle to the ERCOT view.

Overall, the increase in accessible information is important because energy transition occurs on such a large scale, it’s hard to see it happening. California recently fixed up their reporting of auto sales and EV in a nice dashboard, and so did the federal government itself, as Argonne now reports national EV and auto sales. Bravo, and keep it coming.

The US is now working on its fifth year of (net) energy independence. The trend began late in the Bush administration, got going more strongly during the Obama administration, and has stayed on trend through the Trump and now Biden administrations. None of these four administrations undertook any policies at all that crimped, suppressed, or held back US domestic production of oil and gas, which are now once again at all time highs. The big game changer came under Obama, when wind and solar ignited. Today, the 15% share of wind and solar on the grid means the US can export even more coal, and more natural gas, through LNG. That too—the LNG export approval wave—also started under Obama in 2014, and it has gone from strength to strength.

The US produces energy, consumes energy, exports energy, and still imports some energy—mostly crude oil that simply comes here to be transformed into products, and then is shipped back out again. The result is that the US, after being a heavy net importer of energy for many decades, is now a net energy exporter. Long may you run.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to the Gumroad storefront.