Punctuated

Monday 18 April 2022

California intends to phase out the sale of internal combustion engine vehicles by the year 2035. But this is a classic following-sea policy, one that appears after a trend is already underway, and creates an optimal safe space for politicians. In other words, with EV market share hitting 13% last year, the number of ICE sales 13-14 years from now are already on course to be scant. A concept worth remembering: before the end of this decade, EV will be not only cheaper to operate but their sticker price will fall below if not well below that of ICE vehicles. In 2035 it will be starkly irrational to buy an ICE vehicle, unless one is purely seeking novelty. So, when The New York Times described the plan as “aggressive” it revealed once again that the press really doesn’t understand growth, adoption, and curves over time.

The US currently has roughly 280 million registered vehicles, and 36 million of those are parked in California. But perhaps more revealing is that half of all California’s vehicles are in the five large counties of Southern California. So it matters a great deal to the trajectory of emissions whether local governments—say, at the city or county level—take action to limit miles driven. The Gregor Letter routinely touches upon this particular issue, but it’s worth reminding that California exists under almost total Democratic control, and could institute at any time congestion charges that would lower miles driven. The political path with the least risk by contrast concentrates on making sure that no owners of ICE vehicles are inconvenienced, however. And that’s why we see abysmal, short-term plans like the state’s willingness to blow billions, yes billions, on gas tax rebates.

To California’s credit, it has at least undertaken all the policies one could pursue to transition its vehicle fleet—except for policies that would attack ICE vehicles. And yes, this includes higher petrol tax regimes that began their phase-in several years ago. All good. But as many energy experts and modelers point out, the US both as a nation and through individual states has already made enormous gains in decarbonization through the shut-down of coal, and the mighty ascent of wind and solar. Transportation emissions are now the great game in US climate policy. And that’s bad news, frankly, because US transportation policy has been terrible for decades, and unbelievably is at least as bad now, if not worse.

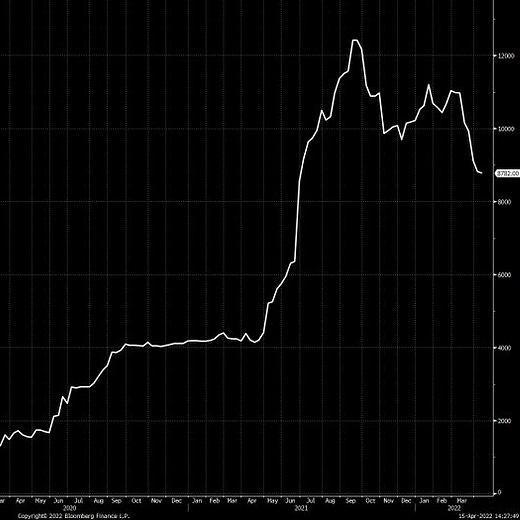

The IEA announced a second cut to its 2022 demand forecast, adding to its previous downgrade in March. Combined, this lowers the agency’s demand forecast from a high in February at 100.6 mbpd to an April estimate of 99.40 mbpd. And we are just getting started.

Meanwhile, BNEF slightly upgraded its estimate of global EV sales this year from 10 million to 10.4 million. This volume of growth is implied in their forecast that the aggregate global EV fleet will advance from 16.0 million on-road EV in 2021, to 26.4 million this year.

Using the estimates from the 7 March issue of The Gregor Letter, War Zones I, which formulates that for every 10 million EV on the road about a half a million barrels per day of oil consumption are avoided, the 26 million EV that are expected to be on-road by year end will, in the aggregate, avoid about 1.2 mbpd of oil. That is not small. Indeed, during normal economic growth of the past decade, 1-2 mbpd of oscillating demand growth has largely described how the world moves forward from year to year.

Those who model year to year demand growth in oil therefore now need to start incorporating the collective effect of EV adoption. Further, it must be pointed out that the two domains currently in the lead of EV adoption, China and the EU, have ICE vehicle fleets with far better fuel efficiency than North American fleets—so the bonanza of displacement that’s about to arrive will gain extra oomph when the US fleet starts to turnover. Add it up. We could see nearly 36-38 million cumulative EV on the road by the end of 2023, 50-55 million by 2024, and 75 million by 2025. So, we are already making the move now from the sale of 10 million new EV per year, towards 20 million EV per year—or, in other words, from avoiding a half million barrels per day of new oil demand per year to one million barrels per day. That is a significant drag on any growth expected by the oil industry, or its observers, and is another reason why 2019 is standing strong as the year global oil demand entered a flat, no-growth period.

The world is going to lose a portion of pre-war Russian oil production as the duration of sanctions lengthens and domestic output degrades. While the current geopolitical conversation focuses on political constraints to the flow of Russian oil exports, less attention is being paid to the risk—nay, certainty—that Russian production itself will degrade under a lengthy sanction regime. Let’s consider, for example, the two sanction periods that affected Iran’s oil production. Describing these effects is pretty easy: Iran has shown a long term ability to produce about 4 mbpd of oil, and the two times it’s been sanctioned the past decade domestic production has fallen by 35-50%. You can see that in a recent EIA chart here.

Russian oil production faces multiple threats, however. First, there is the deadening effect of the political sanctions themselves, specifically on Russian oil volumes for export: the international seaborne trade and finance system has already shifted these volumes to other buyers, often at a discount. Second, however, is more serious: Russian oil has been intertwined with western technical expertise for twenty years now. This expertise came through the presence of companies like BP and Shell. The steadiness of Russian production at the 10 mbpd level has no doubt been enabled by this expertise, though it is not easy to quantify. Here, what matters is the withdrawal of that expertise, and how it will affect production going forward as western oil companies make their dramatic exits.

Finally, however, is the broad severance of Russia from the globalized system of parts and supplies. We have had reports since the war started that this severance is affecting everything from industrial production to dentistry. Now come reports that Russian military equipment production itself is feeling the impact, as the abrupt shortage of parts affects tank production. This comes at a crucial moment in the war as most military experts anticipate that Russia is preparing to throw a new round of tanks and troops into Ukraine, something which could potentially develop into the largest tank battle since WW II.

Further reading: readers may enjoy the Russian produced WWII tank battle film: T-34, from which the above still (photograph) is taken.

Technological advances in energy and transportation will not only continue, but will likely get a boost from the current destabilization of the global economy. This of course has happened many times before, and the flowering of energy efficiency gains after the OPEC-led oil shocks of fifty years ago still stands as a primary example. In evolutionary theory we have the concept of punctuated equilibrium, a notion advanced by Harvard’s Stephen Jay Gould. The exceptionally long timeline history of the planet reveals a number of these events, some around great die-offs or other catastrophic lightning strikes—like the Chicxulub meteor that killed the highly successful reign of the dinosaurs and opened the gate to the ascent of mammals—or less acute but more chronic changes, like temperature or sea level changes of the past. Here, I am using the concept rather loosely, however, because Gould’s (and Eldredge’s) motive in their original paper was not so much to identify external events as triggers but to simply push back against Darwin’s gradualism. Regardless, the analogy is useful as it helps clarify how humans, in the modern era, might respond far more rapidly than anticipated to sudden change, economic disruption, and other threats.

Through the fog of the world’s current crises—inflation, war, climate change effects that are already landing, and newly emergent political fascism—it’s hard to maintain visibility. But consider how rapidly the world is trying to reorganize its relationship to the supply and production of natural resources, high end manufacturing like semiconductors, and fossil fuel dependency. One way to think about this moment is that we are moving quickly from an era where it was challenging to take quick action, and challenging to build and deploy, to an era where it will be necessary to erect a vast new architecture for the sake of a better environment. This pivot is discussed at length in a recent Josh Barro podcast, as he interviews energy professional Joshua Rhodes. The point made is an important one: in the second half of the 20th century, environmentalism generally meant blocking construction of new buildings, roads, and infrastructure. This bias likely deepened over the decades into a kind heuristic: everything new is probably bad. And now, at the moment when the world proposes to decarbonize aggressively, an entire generation reared on the trailing idea finds it hard if not impossible to extract itself from this perma-oppositional stance.

That’s why crises are so useful. They recast priorities, shuffling the deck of cards into an entirely new stack. At the front end of the current crisis for example, the idea that Europe can “get off Russian gas” or that the world can mitigate the loss of 10 million barrels per day of Russian oil both seem impossible, if not fanciful. But humans can surprise themselves, thus surprising you and me in the process. What if by simply starting down the road to less dependence on Russian gas by pipeline, Europe discovers it has other means to mitigate, bridge, reorganize, and strive not for zero dependency, but much lower dependency at a rate most thought unachievable? You may have heard this story, but at the outset of WW II, the US built not one but two new oil pipelines each over 1000 miles in length at lightning speed by marshaling nearly 20,000 workers. Scare people hard enough, disrupt them, and resources can and will be unlocked.

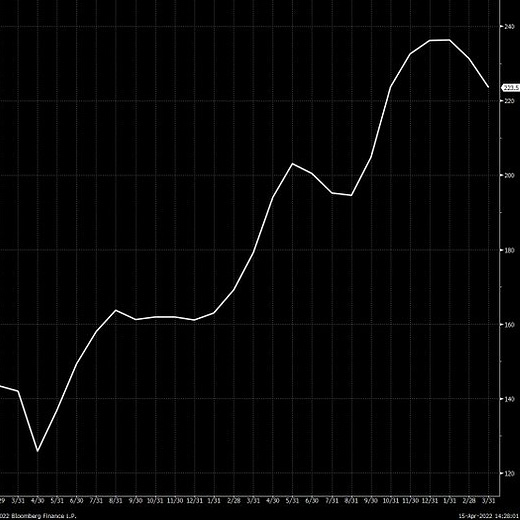

Using a different chemical structure in its battery pack, Mercedes-Benz demonstrated the ability of its new EQXX model to travel 600 miles on a single charge. But it’s not merely the absolute range that’s the story here, because Mercedes didn’t realize this achievement through a larger battery pack. The graph below, from the Bloomberg story, is so astonishing that perhaps it’s best to avoid adding further words here, and let the pictures do the talking.

First they panicked for battery production capacity, and now they are panicking for lithium. About one year ago Volkswagen realized that embarking on a major trajectory in the production of EV meant taking on a new responsibility for the powertrain. Whereas for 100 years vehicle manufacturers only needed to supply an empty petrol chamber with each unit, EV necessitate a far more elaborate in-house power supply. VW’s aggressive move towards Northvolt, locking up most of its future supply, is the kind of move both GM and Ford needed to have made. They did not.

Now comes the company farther ahead than all the rest, Tesla, admitting it too is about to panic: this time, for the sake of lithium supply. Musk hinted that maybe it was time to get into lithium mining. Well, there’s a very simple path to do such a thing: buy a lithium producer (probably a pre-production junior).

The epiphany hitting the automobile industry is pretty normal, and wanting to control lithium supply makes sense, but is tricky. That was one of the points made by Morgan Bazilian at the Colorado School of Mines, and Simon Moores of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence in their joint post earlier this month, EV and Battery Big Talk Must Now Switch to Mining as Supply Chain Bites. While the authors agree the industry has no choice but to gain better control over lithium supply, they allude to a similar push by Henry Ford to gain better control over rubber supply in South America that did not turn out so well. Supply chains are hard.

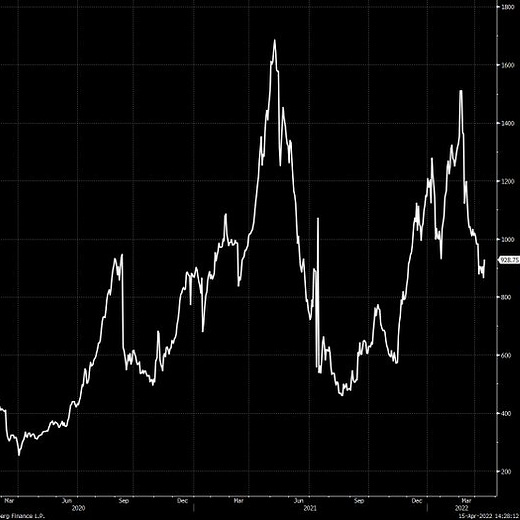

Signs that inflation is probably peaking are starting to multiply. While headline CPI unsurprisingly hit a new high at 8.5%, some components of the measure like transportation, electronics, recreation and leisure showed promise of easing. Used car prices in particular are clearly off their peak, and given the auto sector weight in the inflation readings that is good news. Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal also noted that “the four horseman” drivers of recent inflation are all rolling over:

Importantly, Federal Reserve governor Waller—while stating the Fed was still on track to keep hiking—admitted that inflation “probably had peaked in March.” A simple take is that global economic conditions are precarious, and scary. That’s why market sentiment readings are hitting lows not seen since the worst of the pandemic’s onset. But this also opens up the possibility that many market prices from high oil prices and high interest rates to suppressed stock market prices are at risk of a reversal.

Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, whose photographs of Alberta’s oil sands captured attention last decade, has a new outdoor exhibit coming this summer to Toronto. Burtynsky’s work shares some of the qualities of Salgado in the grandeur of his presentations. But where Salgado has often concentrated on laborers in the developing world, Burtynsky is very clearly focused on the environment, and the scale of our destruction in mining, suburbs, and natural resource extraction.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.