Rates of Interest

Monday 11 March 2019

The US market for electric vehicles is broadening out now, beyond California. For several years the Golden State took about half of all US sales of EV; but in 2018 that share dropped from 50% to 43.6%, as EV growth in the country rocketed higher by 80%. Final data from the California New Car Dealers Association showed the state took 157,659 sales of both BEV and PHEV, out of the 361,000 national total. Contrary to the earlier Gregor Letter estimate therefore, that EV would reach a 9% share of California vehicle sales, EV share reached 7.9% last year. The good news is that EV sales are now spreading rapidly to other states, loosening California’s grip on the market. And, given the continued slide in sales of ICE vehicles, EV should still reach well above a 10% share of all sales this year in California, and may go as high as a 12% share.

The electricity needed to power new EV hitting the road increasingly comes from the growth of wind and solar power. (This is a central thesis of the Oil Fall series). Early data from China, the UK, Europe, and the US shows marginal growth of newly built electricity generation continues to be dominated by the triumvirate of wind, solar, and natural gas. As US data for 2018 was just released by the EIA, I have made up a chart showing the top 18 states where some combination of wind and solar power now provide at least 10% of each state’s electricity sales. While one can certainly discount the very high proportion of wind power in sparsely populated Great Plains states, (Kansas, for example, with just 2.9 million people where wind power has now reached 47.13% of electricity sales), it’s impressive that in larger states like CA, CO, TX, and MN combined wind and solar are right around the 20% mark. More intriguing is the continued level of low public awareness that wind and solar have come to not only dominate marginal growth in many domains, but have now reached volumes more typically associated with nuclear power or hydropower. In less than a decade, we have moved the needle from a time when many claimed wind and solar couldn’t scale fast enough, to new complaints these sources are growing too fast. What a great problem to have! (note: in the chart below, the color gold indicates generation is solar-dominant; blue indicates wind is dominant.)

Wind and solar are a particular type of infrastructure requiring steep, front-loaded investment costs, but which then pay out quietly over 25 years, at very low levels of operational expense, not unlike a bond. Accordingly, it’s always a good time to think about interest rates when considering the future of wind and solar.

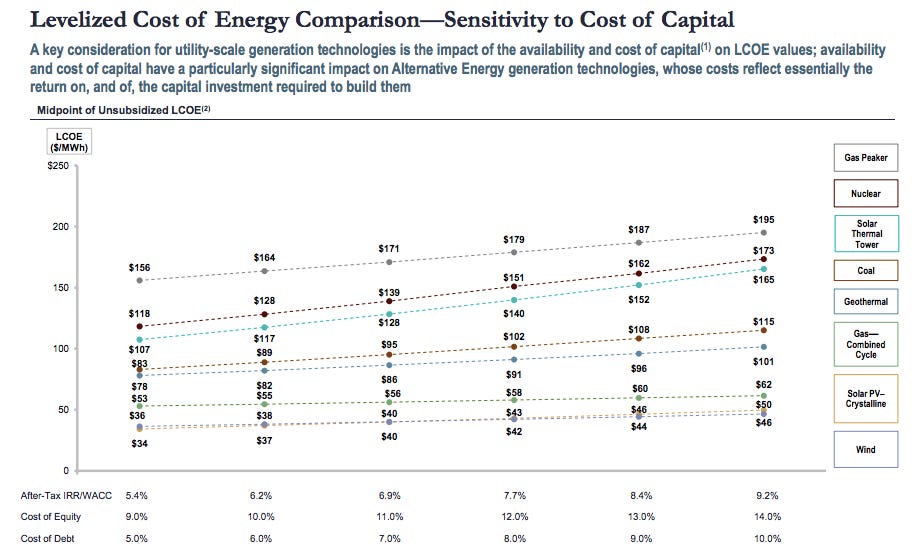

If you haven’t already, you might want to read through the latest report on wind and solar’s levelized cost of energy (LCOE) from Lazard. Published last fall, most readers gravitate to the main conclusions of the report’s update, which ranks wind and solar’s competitiveness both subsidized, and unsubsidized, against other forms of electricity generation, from natural gas, to nuclear, and coal. However, I would encourage you to pay some attention, instead, to Lazard’s illustrative cost-of-capital sensitivity chart. Despite the technologically driven cost crash in both PV panels and wind turbines the past 5-7 years, it’s still the case that capital costs—and yes, interest rates—are highly controlling of investment outcomes in clean energy.

Notice, for example, Lazard’s estimate of solar’s sensitivity as the after tax, internal rate of return/weighted average cost of capital moves from 5.4% to 9.2%. Along this axis, solar’s LCOE per MWh ramps quickly from $34 to $50, a 47% move. Now contrast this high sensitivity to combined cycle natural gas which, in the same comparison, sees its LCOE move more slowly from $53 to $60 per MWh, or just a 13% move.

(To enlarge the chart, click at least once on the image, and possibly twice.)

Needless to say, the low interest rate environment of the past decade has been enormously helpful to wind and solar development. If you’d like to learn more about this relationship in an easy to read essay, please see this helpful 2016 post from Carbon Commentary’s Chris Goodall. The main takeaway, however, is that even as wind and solar have come down dramatically in price—and have concurrently increased their efficiencies (ever larger wind turbines, and,PV panels that capture an increasing percentage of sunlight)—it’s still the case both forms of energy generation face a construction hurdle, in which labor, engineering, and materials must all gather at the front end of a singular event. And the capital cost of that singular event matters, quite a lot.

Now, let’s throw into the mix some recent work on our low interest rate environment from Princeton’s Atif Mian. You are probably familiar with the basic thesis of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, that extended phases of low growth, and low interest rates, create a somewhat perverse situation in which the earnings to capital outrun the earnings to labor. To put this more plainly, the rich get richer as they collect their rents and the value of those rents is maintained amidst low inflation, while wage growth stagnates for labor, causing worker wealth to fall behind. In the recent work by Mian and his co-authors Ernest Liu and Amir Sufi, “Low Interest Rates, Market Power, and Productivity Growth,” something akin to this Piketty effect is shown to impact the industrial sector, conferring a real advantage to corporate leaders, and pressuring the ability of followers to compete. In Mian’s explanatory twitter thread, falling interest rate environments while beneficial have an offsetting “strategic effect” that fosters market concentration, and stifles productivity.

This got me to wondering. As wind and solar and electrified transport increasingly dominate the global growth path over the next two decades, might we see a time when large well capitalized entities come to equally dominate the ownership of those assets, and the business of their deployment? My answer: yes—but when it comes to generation, industrial concentration or even monopolistic domination may be seen as less of a problem. Here’s why. Generation is already becoming a commodity. If Orsted comes to dominate a future offshore wind industry in the US, and companies like Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Energy continue to amass wind and solar assets, this will not interrupt the downward trend in the cost of new generation. So if large companies win the game of inches already in play in wind and solar (the sustained competition to undercut rounds of bidding by pennies) that is probably to the benefit of society. We need lots of supply on the generation side, and getting it built as quickly as possible has system-wide effects.

Rather, one might want to develop some concern for industrial concentration in energy storage. As mentioned in the January letter, Something About Storage, the hottest area for markets will almost certainly be the storage area. For, storage is the nexus where increasingly cheap generation will ultimately be distributed through both market mechanisms to govern pricing, and, technology that will govern algorithmic time-shifting and price arbitrage. In a future powergrid, storage—not just dumb boxes but smart-layer-enabled devices across the network—will be the key platform. And owning storage, or being able to build storage more competitively than others, or both, will confer the most advantage. In such a world, large incumbents would potentially monopolize storage capacity—much like an Amazon dominates today’s internet backbone—and the countervaling force to this domination would only come through tech innovation from entrepreneurial start-ups.

For what it’s worth, it’s my view the present secular era of low interest rates will continue. Falling global fertility rates, continued high levels of consumer debt, and the fact that industrialization, the heavy kind, is largely behind us in terms of growth points to a best case scenario in which global GDP is increasingly composed of improvements to the existing built environment, and to human well-being. In such a world, we will have ample time to ponder further the various advantages, and also distortions, created by low interest rates.

Apple, Google, Microsoft and Amazon have all been aggressive in building out wind and solar power, in an effort to match their increasingly heavy demand for electricity. In late December, I was interviewed by WIRED magazine on this topic, and the piece notes the tech sector so far has accounted for the buildout of a whopping 7 GW of new renewable capacity. But now comes Google with an AI twist, one that may lessen the unpredictable variability of wind power. You see, not only are wind and solar power variable, but they are both sub-optimally predictable. And grid operators want to know in advance, and need to know in advance, whether demand or supply will break out of more predictable envelopes. Again, electricity is a market. Ergo, the ability to ramp supply to meet spikes in demand has value. The ability to hold back demand, when supply is constrained, has value. And the ability to tell a grid operator when you will do either, also has value.

Google has now charged into this marketplace of electricity, announcing late last month that DeepMind, it’s artificial intelligence unit, has focused machine-learning onto its own wind production. For this effort, Google now claims that day ahead, or even two-day ahead, wind production can be predicted with better accuracy. While Google did not give exact details on how they are trading and monetizing this value with grid operators, the bottom line according to Google is that 36 hour predictability—that is, the increased ability of Google to sell wind power at a predictable time to the grid—raises the value of wind by 20%. And frankly, given similar experiments already taking place across the vehicle-to-grid space, that seems like a reasonable claim.

Assorted Briefs: The public is perhaps, just now, becoming aware of the major steps China is taking towards electrified transport, because 60 Minutes did a large segment on the EV story this past weekend. Meanwhile in India, early indications are that coal projects continue to be cancelled, as the push for new wind and solar power accelerates. According to PV Magazine, solar alone made up 50% of India’s new generation capacity last year. In the Indian Parliament, meanwhile, Piyush Goyal, former energy minister and current minister of Railways and Coal, explained India’s electrification plans and its bold intention to electrify transport through the adoption of EV. Back in Europe, emissions in the UK fell to levels last seen in 1898, as coal power is now mostly erased from the British landscape while wind power (and some solar) pushes towards 20% of UK electricity. Given that offshore wind power has been such a technological and economic success (coastal Yorkshire now hosts the world’s largest offshore windfarm), the UK government decided just last week to push forward more aggressively with wind power, aiming to have 30GW installed by 2030. Finally, there are now three very good reaction pieces to read, in the wake of the release of the Green New Deal. Please see my tweet-thread below, that highlights essays by Michael Liebreich, Ramez Naam, and the New Yorker’s John Cassidy.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.