Regime Change

Monday 5 October 2020

Markets are getting into position for a Biden presidency. Macro analysts both inside and outside the US are also beginning to align in their views of how a new administration will affect investment, interest rates, employment, and the US dollar. As most can already discern, the US has come through a 40 year period in which monetary and tax policy were the primary tools to create growth. The problem, already well established, is that diminishing returns have set in on both of those strategies. The US suffers from one of the longest running infrastructure deficits in the western world, which sees global level cities such as Boston, Washington, New York, and San Francisco trying to operate on infrastructure last updated in the 1980’s, at best. At worst, many American cities are still struggling with pre- World War II transport and water systems.

When you begin to comprehend the trillions of deferred maintenance and investment that now overshadow the US economy, it becomes far easier to absorb what’s coming next from a Biden Administration. The entire national railroad network needs modernization; and myriad US cities need completion funds for commuter rail resurrections that have appeared in fits and starts the past decade. Government vehicle fleets will be electrified (the US Post Office alone controls about 200 thousand vehicles) and building codes will be transformed, likely through incentives, to incorporate solar and storage in everything from schools to other municipal and federal buildings. The green light from Washington will add speed to many trends already in place: solar, wind, and offshore wind especially. If you are a second or third tier city in need of intermodal upgrades to get products to market, or to host deployment operations for offshore wind, you will finally receive federal funding.

Macro and economic forecasters and advisories see what’s coming, and draw the obvious conclusions. Treasury yields will likely stop falling, at least for a while. (It bears remembering that treasury yields rose for about one year, starting in early 2009, as reflationary policy began to take hold. And then they fell again, even as the recovery made slow progress). Investment flows will favor industrial companies, and that will likely bring an end to both the outperformance and the momentum of the megacap technology names. The US dollar will weaken—not because something fundamentally weak will be taking place in the US, but rather, because the US dollar tends to assume a relaxed posture when global trade is running normally. The difference this time around is that consumption will not be restricted to retail goods, but will expand to include the big, heavy engineered equipment needed for construction and modernization. And of course, not all the capital goods required to supply a decade long infrastructure upgrade will be sourced domestically in the US. If you recall the effect China’s modernization buildout had on European capital equipment manufacturers, for example, this era will be similar.

To use a single US city as an example, it’s rather effortless to lay out what needs to happen next for the City of Boston. Despite incrementally resurrecting its commuter rail along historic rail beds that were originally laid down before WW1, the city’s entire transportation network needs to be overhauled. The subway system needs to have most of its rolling stock replaced. Same too with the commuter rail system. And the footprints of both need to be either expanded or enhanced with station upgrades and tie-ins to other networks of cycling or walking routes. The Boston waterfront needs climate hardening, as seasonal high tides now regularly invade the lower portions of the financial district. Finally, Boston has access to broad undeveloped land in its new South Waterfront district and the city like many US cities is now quite short of housing. The implications are rather straightforward: Boston is just one of 50 large US cities that need investment. Doing so will not only boost its GDP in the short term, but because the upgrades are aligned with efficiency, the longer-term GDP outlook would also be substantially improved.

In my journalism work over the past few years, many of the interviews I’ve conducted with urban designers and infrastructure professionals have produced a rather unified message about the problem which has beset the United States. Local populations in Boston, Los Angeles, and many other urban areas have shown an increasing willingness to tax themselves in order to make long overdue investments. So, there is not a collective action problem facing the US, as many of the critics habitually point out. Rather, there is a completion-funding problem—one that is also bound up in permitting. Let me explain: if replacing all the rolling stock in Boston’s two rail systems, while also expanding each system, requires X amount of capital, then it’s quite likely that Massachusetts voters would happily take on 40-60% of that burden through a bond offering. But traditionally in the US, the federal government has taken a cornerstone role not only in funding, but in permitting. By providing both the funds necessary to complete generational projects, the federal government typically becomes a co-applicant in standard environmental reviews. Both influences are greatly helpful in getting infrastructure built, because federal involvement then clears the risk-path for private capital to also participate. There is a ton of private capital that would love to own the future cash flows either from construction bonds, or income generated by infrastructure itself. Moreover, the US not only has a 40 years backlog of projects to pursue, but needs to tackle these challenges on much faster construction timelines. This is all very possible, and much of the criticism of building infrastructure that’s become common in the past four decades is very much the result of the absence of one, key player who used to play the deciding role: Washington.

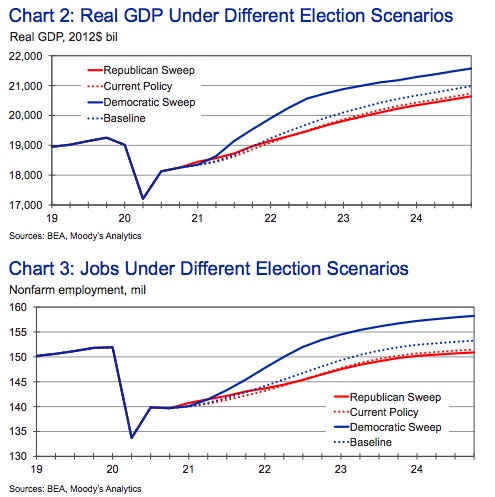

Economic forecasters who’ve started laying out a post Biden boost to economic growth include Goldman Sachs, Nouriel Roubini, and in particular Moody’s, which released a full report late last month. It’s not exactly rocket-science: if the federal government aggressively gets back in the game of making long needed domestic investments, then GDP is going to be meaningfully lifted in both the short and long term. The below chart is from the referenced Moody’s report, The Macroeconomic Consequences: Trump vs. Biden.

Not only is Joe Biden now highly favored to win the presidency, but a broad based polling surge in his favor strongly suggests Democrats will also gain control of the Senate. Because polling results are moving quickly, I have updated the electoral college map once again. In the last letter, I explained that an outlier poll showing a huge Biden lead in the state of Maine eventually transitioned to reflect similar strength in the state of Minnesota. Now, that same outperformance has started to affect the state of Pennsylvania, and quite importantly, the states of Ohio and Iowa—enough so to tip them into toss-up status. Just to remind, there is a commonality to these states as they are older, white, have large rural populations, and in many cases are losing population as successive economic expansions pass them by. First, let’s look at the latest EV map:

In the above scenario, Biden: 1. wins all the states that Hillary won, 2. takes back the three midwest states that Trump barely won in 2016: PA, MI, and WI, 3. wins a new state for Democrats, AZ, 4. pushes OH, NC, and FL from deep red back into toss-up status where they have been for some years. And the kickers, two small, and two large: the piecemeal congressional district of Maine (ME-02) falls back into Democratic hands, as does Nebraska’s (NE-02). And finally the big shock: the states of Georgia and Texas are toss-ups. That is both unthinkable, but also the new reality. The implications are huge: if Texas and Georgia are now toss-ups, then long-shot Democrats running for the senate in Alaska, Kansas, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi are suddenly in contention. And the polling on the senate bears this out.

Thus, we must now favor the outcome that not only does Biden win the presidency, but control of the senate falls from Republican to Democratic hands. Indeed, it is becoming quite easy to forecast that, at minimum, Democrats will pick up a net +3 seats, placing the senate in a 50-50 configuration. At that level, New York’s Chuck Schumer then becomes majority leader via the constitutional route which deems that Kamala Harris, as vice-president, becomes the senate president, providing the 51st vote. While forecasting the senate is far more difficult, Democrats will likely pick-up seats in Arizona, Colorado, North Carolina, and Maine, while losing Alabama, for the net gain of +3, pushing the senate to 50-50. But now it also seems likely the Democrats will get at least one, if not two, of the pick-up opportunities in the following states: Alaska, Montana, Kansas, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Editor’s note: the news that President Trump tested positive for COVID comes as the Gregor Letter was already in production. In the same way that the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg has, or will have, undetermined effects on the election outcome, so too is the news of the President’s illness. Because it’s difficult to say something useful when newsflow is this accelerated (the revelations of the President’s tax picture, a Presidential Debate, and now a widespread COVID breakout in the White House have all occurred in less than seven days) let me suggest the following: keep your eye trained on the remarkable stability in the polling. Biden has held the same lead he holds now for many months, with only slight fluctuations in his disfavor appearing in August, and now a new fluctuation very strongly in his favor appearing in September, and especially here in early October.

Post election dramas are promised (and feared), but are unlikely to be realized. Readers both outside and inside the country are understandably focused on the efforts of Republicans and the Trump team to either thwart the counting of votes, or create mayhem in the post election phase. At play in these fears is the memory of Bush vs. Gore in 2000, which likely feeds into a broad suspicion that the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) can reverse the outcome of the election. This is however a flawed example, and a flawed precedent. Here’s why: most of the states that many fear will see a post-election series of lawsuits have, themselves, very clearly outlined rules for how they will accept, and count, mail-in ballots. Florida in the year 2000, by contrast, not only counted all the votes but conducted a law-mandated machine recount of all the votes which still resulted in a statistically tiny gap between Bush and Gore. It was from that very small patch of ground that both the Florida Supreme Court and SCOTUS got involved—mostly over disputes over how many times to recount the vote.

States like Ohio for example have a very clear set of rules for how they will count the vote that comes in person on election day, the early in-person vote, and the mail-in vote. The rules are quite clear on the latter: all ballots postmarked by election day will be counted up to 10 days after election day. While Ohio is controlled by the Republican Party at the state level, it should be noted the secretary of state for Ohio has been quite clear and active in communicating these rules to the public. What opportunities therefore would the Trump team have to use SCOTUS to intervene, and stop counting the ballots after election day—as Ohio has already explained it will do? Few, if none. State supreme courts and also the US Supreme Court, when in conservative control have shown a fairly consistent, distaste for allowing any ad-hoc rulemaking or rule circumventing. The chances that ballot counting would suddenly be halted in Ohio are the same for halting vote counting in California, which typically takes at least 4 weeks to tally all the votes.

Here is your general guideline to assess the merit and the likelihood that SCOTUS would intervene heavily enough to change the outcome of the election at the presidential level: is the state at issue—whether it be Florida, or Pennsylvania, or Ohio, or North Carolina—making up ad-hoc rules, after the election? If SCOTUS determines as such, they will most certainly act. But if the Trump team sues a state, despite that state following the rules it laid out for itself before the election, then expect SCOTUS to show thumb-down on such efforts from the Trump team.

Based on current polling, which now favors a thunderous blue wave of Democratic votes that would obliterate small margins, these risks are also likely to be moot. Indeed, there’s a possible twist coming to this storyline. Most expect the Trump team to make broad efforts to stop vote counting after election day. But the results may see a flipping of the script, with Trump and Republicans staring down a broad election loss on November 3, and then pleading with the country to please wait, until all the votes are counted.

While the Gregor Letter base case for economic recovery remains unchanged, it’s now time to lean towards the possibility that a 2021 recovery will proceed at a faster pace. Yes, this is tricky. Because, as you are no doubt aware, the economic problems created by the pandemic are actually getting worse. Layoffs by major US employers have started up again. The most recent jobs report (the last before the election) showed the pace of the recovery is slowing significantly, as job creation came in well under expectations in the Friday 2 October release. Simply put, the latest economic data unsurprisingly shows that the bridge Congress built to get the unemployed to the other side of the pandemic has started to falter. Incomes also fell for the first time in August, for example. So in the near term, the deep crater left by the pandemic’s massive impact has not gone away, at all. And the longer that crater stands as an open wound, the longer we must extend our timeline for recovery.

But we must also stay open minded, ready to accept that radically different policies will pace and lead expectations, catalyzing a faster 2021 recovery. Assuming Biden is certified as the winner in the electoral college in early December, and that Senate control has fallen to the Democrats, you can expect the following signals to emerge. Each will have a major impact on markets, and the employment picture.

Clear articulation of new pandemic management policy, one befitting a modern nation. This would include a massive rollout of testing capability, fresh economic support to affected workers that could function like a temporary UBI, and better guidelines so that states and institutions don’t have to make up rules on their own.

Perfecting and fixing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to align not only with demands of the pandemic, but to circumvent potential actions by SCOTUS. Solutions to the problematic gaps in ACA have been waiting in the wings for years, stymied by Republican control of the Senate.

Release of a major, decade long plan to invest in US infrastructure, with clear signals as to how funding will land across the various regions of the country. The initiative will of course greatly favor clean energy, reduced consumption of fossil fuels, and broad electrification.

Because markets (and humans) are forward looking, a broad range of industries from healthcare to energy to construction and engineering would obviously start moving immediately, making preparations for 2021. This would shift the trajectory of the recovery in a very positive direction (clearly what macro forecasters like Moody’s are expecting). The US dollar would stop strengthening, boosting global liquidity, and many other industries outside the US would also begin to respond to US plans.

Ford Motor Company announced firm plans to produce an all electric version of its wildly popular truck, the Ford F150. The company will invest $700 million and, in a marriage of old and new, has chosen the historic River Rouge complex as the location for the project. The details of the truck itself are fascinating, and likely to attract buyers looking for even better speed and torque, than the ICE version. But the real kicker has to be Ford’s decision, or perhaps realization, that the larger battery grants useful bi-directional capabilities, effectively make the truck a rolling power plant. The EV 150 will be able to power not just itself, but can be switched to provide electricity to tools or other needs at any job site.

Oil prices fell substantially, further confirmation that the mini-recovery in prices since March has now terminated. Coverage of oil and the oil market in The Gregor Letter is also likely to decline as oil is no longer the story. While the acceptance phase will take time to develop, financial media needs to understand that in the years ahead, oil price fluctuations will carry no signal, and global electrification should be put at the forefront of most energy stories.

Small scale nuclear is making progress, attracting investment and research development. Bill Gates’ nuclear venture, TerraPower, continues to pursue small modular reactor (SMR) technology and in a partnership with GE Hitachi is developing a reactor that would be paired with storage. That’s a great idea. Elsewhere, MIT is chasing ever elusive fusion, and perhaps they have made some progress according to this story in the NY Times. I wouldn’t bet on it, though. Just to remind, The Gregor Letter does in fact have a position on nuclear, one that is both constructive but narrow. From the 25 March 2019 issue:

The prospect of new nuclear therefore now faces not one, but two hurdles. With a negative learning rate, nuclear power—already expensive—never gets cheaper. So nuclear both here and elsewhere in the world has fully lost the cost argument. More challenging is that nuclear has now lost the climate-solution argument. If India can build 0.648 GW utility scale solar plant in less than a year, and if the United Kingdom can transform its power grid in less than a decade, killing coal, and taking combined wind+solar from 2.5% to over 18% of its total electricity, then the longstanding argument that only nuclear can quickly decarbonize power systems has considerably weakened.

And yet. Ironically, it may be the very real success of wind and solar deployment that opens up a better argument for nuclear: as marginal amplifier, to make current progress move even faster. Here, we see that the cost argument has two sides. Yes, nuclear is now the most expensive new generation out there, and its ROI is second-rate, given its long construction timelines. But so what? As estimates of future climate-change damage ratchet upward, we should care less about up front price tags and more about outcomes that bear heavy losses. Moreover, although combined wind and solar are now moving very rapidly, and even with storage solutions also now emerging, in many domains the gaps in needed supply are being furnished by new natural gas. And natural gas, while far better than coal, will stand as a new emissions barrier in the years ahead.

Accordingly, I now believe we should build some new nuclear. Not alot, but some. It doesn’t matter how much it costs, and it doesn’t matter that it may take ten years to build. If so many climate analysts are now in agreement we’ve got about 10-12 years to substantially re-direct the current growth path of emissions, then having a new population of nuclear capacity arriving at the margin, next decade, would be greatly supportive of the much larger wave of new wind and solar and storage.

NextEra, the leading-edge wind and solar utility of the United States, has surpassed ExxonMobil in market cap. Exxon’s market cap has declined by half for obvious reasons. But to put a finer point on it: the oil in the ground controlled by Exxon is worth far less in both the near and far future than previously understood. And, the capital equipment under Exxon’s control to extract and refine that oil has also meaningfully declined in value. And these declines create further, ongoing risk to any party who owns shares in XOM, thus requiring a higher equity-risk premium. By contrast, NextEra owns and continues to develop far less risky wind and solar and storage projects, which all have much higher visibility in terms of their risk, and cash flow. So, an investor in NEE is not going to be paid a premium to take on the risk of owning such assets, also for obvious reasons. Yes, this is all about the downfall of the oil and gas industry, now that it’s a no growth business. But far more important is that renewable energy offers not only better returns to society, to but to investors as well. More of this—alot more of this—to come. FT, with the story. N.B. it is probably more correct to say NextEra has matched, rather than exceeded ExxonMobil’s market cap, right around the $140 billion level.

Path dependency should never be far from our considerations, even when there’s evidence to support rapid change. The global economy is very likely at a welcome tipping point as the mighty part of the adoption curve looms in EV, wind, solar, storage, and clean infrastructure. And there is good reason to expect these transformations are about to proceed more quickly than ever before. Just take care to remember path dependency; a powerfully enduring phenomenon in systemic change. While incumbency has taken some big hits of late, and will soon take more, incumbency has an uncanny skill to leave its mark, like a shadow.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

Photos: 1. South Station, Boston, 1902. 2. Douglas Aircraft plant, during World War II, Long Beach, California.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.