Resource Alarmism

Monday 22 February 2021

Tesla Corporation’s decision to invest $1.5 billion into Bitcoin has unleashed the usual hyperbolic claims about the cryptocurrency’s energy footprint. The Financial Times, for example, deemed it an act of environmental idiocy. But perhaps it would be better to question such a strategy more conventionally, and whether this is a wise use of corporate cash. The company finished the year 2020 with roughly $19 billion on its balance sheet. Not exactly the kind of surplus that warrants shifting 8% to a speculative asset. Tesla is no Apple, which has carried $65 to $100 billion of cash on its own balance sheet in recent years.

Bitcoin’s growing demand for electricity is currently estimated between 75 and 125 TWh per annum. Actually, the number moves around alot, depending on continually updating analytics from the University of Cambridge or other sites like DigiEconomist. The range of uncertainty itself is worth noting. Cambridge cites a theoretical upper bound of 330 TWh per year, and a lower bound of 40 TWh per year. Certainly not a “who really knows” situation, but these are still exceedingly small numbers on the grand scale of global electricity consumption. In 2019, the world consumed over 27,000 TWh of power according to the BP Statistical Review. Accordingly, the annual variability of normal global economic growth, a hot summer in Europe that increases the call on cooling demand, or a country-level shift in the use of coal power (China) would all exceed Bitcoin’s estimated annual power demand. As cited in a recent letter, Ice Melt, China created 75 TWh of new electricity last year from solar alone. And further context: the US consumes about 4,000 TWh per year and China now over 7,000 TWh. The process of bringing electrification to populations in the developing world, on an annual basis, also propels global demand growth for power. Are we going to decry rural electrification in Asia, even if much of the new power is from solar? In the five years between 2014 and 2019, total global electricity demand grew by nearly 3000 TWh. Looking ahead, we are currently in the process of shifting large blocks of the global economy, transportation especially, to power. And much of that new power will be clean.

This is why you don’t want to find yourself shouting out to the heavens that Bitcoin’s annual power demand, at 0.277% of the global total (75/27,000), is a moral and environmental disaster. While I enjoy the passion of such twitter threads (especially the well written, persuasive rhetoric of the one just linked) the hyperbole of such claims simply doesn’t match the scale or the proportions in question. One can reasonably hold moderate, justified concerns about the advent of cryptocurrency. But there is an equal concern: the way in which society as a whole often defaults to intuitions to claim, wrongly, that the world cannot possibly deploy electric vehicles because “they will certainly have to run on coal power,” or, to fight more generally any kind of economic development (including electrification) because “this simply switches humanity’s dependence from oil to other commodities.”

Hyperbole happens to be the specialty of Bitcoin advocates too. While many mining operations are hooked into renewable sources of energy, often taking up surplus power when wider grid demand is low, it’s a bridge too far, unfortunately, to claim that Bitcoin is helping the environment by utilizing energy that would have been wasted. Building a utility scale battery and taking up surplus wind power at night to feed back into the grid is helping the environment. But virtual battery operations, like the one used by this Texas Bitcoin miner, may get close to such a service but don’t quite cross fully into “helping the environment” territory. The grandiosity associated with the Bitcoin community is well known, and the claims about Bitcoin’s ability to solve intractable human problems are embarrassing. Sorry, but Tesla’s corporate decision to convert 8% of its cash to Bitcoin is highly questionable. I will remind: taxes, liabilities, payroll, and costs must be paid in dollars.

In truth, every year sees some electricity-using industries decline, and others appear, and naming Bitcoin as a statistically significant outlier, either way, in this evolution of the global economy is wrong. So the Financial Times’ claim that Tesla’s purchase of #BTC is climate idiocy is, itself, silly. The FT might as well write a long investigative series, projecting the damaging impact Tesla will have on global lithium extraction over the next 10 years. Unfortunately, this type of analysis gets very close to a rather dishonest, reactionary trend of late in which voices that never cared about the environment in the first place race to tell us that “green energy” is not going to be green at all, and rather comically cite all sorts of wildly wrong statistics about the millions of tons of coal that will be required to deploy global wind and solar power. Responsible observers are, by contrast, quite sober about the renewed call on natural resources that energy transition will require. And the salient point remains the same: this aggregate call is dwarfed, absolutely dwarfed, by the environmental impact of running the system as it is for another 50 years on fossil fuels.

Perhaps semiconductors will generate the next wave of resource alarmism, because energy transition is clearly going to need lots of chips. Indeed, we are only in the second or third year of the great global S curve in which wind, solar, storage, and EV are now rising majestically. And already we have chip shortages? General Motors is short, VW, Bosch, and Continental are short, and pretty much the whole world is short. The benchmark Van Eck Semiconductor ETF was barely scratched in last year’s stock market crash and taking out that brief dip the ETF has risen from roughly $150 at the start of 2020 to over $250 today. Recent reports indicate one of the ways the industry is handling the crunch is by disallowing customers from hoarding supplies, requiring them to scale their purchases to actual near term industrial demand. Nvidia reportedly decided to produce a video card that would throttle back if/when used for cryptocurrency mining in order to better create card supply for its preferred customers: gamers. Although the company later denied the card would operate as such, it’s a sign of the current fever. Which probably gets worse, before it gets better.

With an appropriately timed macro view, the research outfit of TS Lombard has gone so far to suggest that semiconductor manufacturing capacity has therefore been elevated to a geopolitical asset, with mounting risks and pressures, not unlike oil. Lombard suggests tensions of this kind will now migrate from the Persian Gulf to East Asia, Korea and Taiwan especially. I think we should be wary, however, of the impulse to declare that chips are the new oil. This phrasing is seductive. I myself have used it with regard to electricity, and I still think that formulation is true. But the comparison has become popular—especially at a time of slowing oil demand—and many resources (data is the new oil!) have been impulsively drawn in to the phrase.

All this said, mounting the expansion of new semiconductor production capacity will be a challenge. Yet, perhaps not as difficult as bringing 2 mbpd of new oil online. Consider it a preview of the decade ahead: one characterized by scary, short-term inflationary pressures that will seem awfully convincing at the time. Pressures that will segue—more quickly than most expect—into new supply.

US interest rates are rising rapidly as reflationary policy and an industrial recovery gather strength. This has predictably stoked fears of inflation, or rather, an emerging certainty that inflation will not only arrive, but that it will violently derail the US Federal Reserve’s policy commitment to keep rates lower, for longer. There is however a paradoxical dynamic, latent in this prospect. If market participants, despite protestations from the US Fed, work themselves into a hard belief that inflation is coming by selling off treasury bonds prematurely and too aggressively, then market interest rates will indeed rise. Worse, if the stock market goes into decline at the same time this also could contract liquidity, and the two effects together could tighten monetary conditions. This would be especially true if the US Dollar also rose, exacerbating the reaction. The dollar has a nasty habit of doing just that. This would then slow the economic recovery, slow hiring, and the interest rate increase that everyone expected would soon fade. Paradox: a premature fear of inflation could slow the economy, causing nascent inflationary pressures to ebb.

But there’s a different outcome that seems far more likely: as the industrial recovery unfolds, prices do indeed get pushed up—but those prices trigger actual hiring that increases production. Supply then meets demand, rather quickly. Given that the year is 2021, not 1921, with all the supertrends that epochal difference implies, one should favor a quick taming of inflationary pressure through increased output. And better still, through increased productivity. To briefly remind, the world has been in a deflationary phase for at least two decades. Fertility rates continue to crash from high levels in developing economies, and even from low levels in developed economies. Global production is increasingly digitized, optimized, maximized. Manufacturing learning rates are ferocious, and everywhere. Software is still eating the world (Marc Andreessen), and global labor is continually marshaled into the available workforce through communications technology. To say these things is hardly utopian. Rather, these supertrends are quite measurable and no data point tells the story more succinctly than the inability of global labor to get pricing power, through increased wages.

There’s another lens through which to project inflation’s future inability to gain sustainable traction: output gaps. Two economists, Paul Krugman and Robin Brooks, have long taken the view that spare capacity is far greater than is commonly measured. Brooks has a fun acronym to describe his posture: #CANOO - Campaign Against Nonsense Output Gaps. And Brooks in particular often hoists this ongoing analytical failure into his remarks. For example, in the tweet below, Brooks praises the FT’s Chris Giles for observing that the EU is likely to once again make a policy mistake on the question of stimulus, in part, by getting the output gap wrong.

For all the structural reasons mentioned (the suite of supertrends that have made our current age mostly deflationary) there is a strong case to be made that Brooks is right. Western world or indeed global output gaps are far larger than is currently assessed, and accordingly, stimulus should not be feared as the Europeans serially fear it—for it will take far more time for such stimulus to actually hit the limits to spare capacity. But markets are made of people. And if people decide that the US Federal Reserve will be knocked off its lower-for-longer stance, then we will indeed have a slowdown long before we locate the real border between expansion and actual, problematic inflationary pressure.

Jeff Currie of Goldman Sachs believes we are entering another commodity supercycle. Well, I simply can’t agree. In a recent Odd Lots podcast with Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway, Currie makes a number of excellent points about behavioral factors that will lead to such a supercycle. In particular, he identifies new policies that favor getting money into the hands of people directly, rather than through the usual circuitous, trickle down pathway. On this I agree. There are many supportive factors to a period of robust commodity demand, especially in a post-pandemic world. More broadly, The Gregor Letter has been quite clear that energy transition itself, while deflationary on a grand scale, will plow through the earth’s crust for years, turning up demand for natural resources.

But supercycle is a big word. The proof to apply to this question whether or not there’s a large sovereign on the planet about to enter an industrial revolution. That was the case in the last supercycle, roughly from 2000 to 2010, when China transformed itself and by extension the world. Presently, the US may finally invest in itself and raise the minimum wage, and China is clearly heading more deeply into its domestic consumption phase. These factors will certainly be price supportive of commodities. But it must not be forgotten: the biggest trend on the planet right now is energy transition and its inevitable removal of fossil fuel waste from the global economic system. That’s clearly supportive of some commodities, but is no recipe for a supercycle.

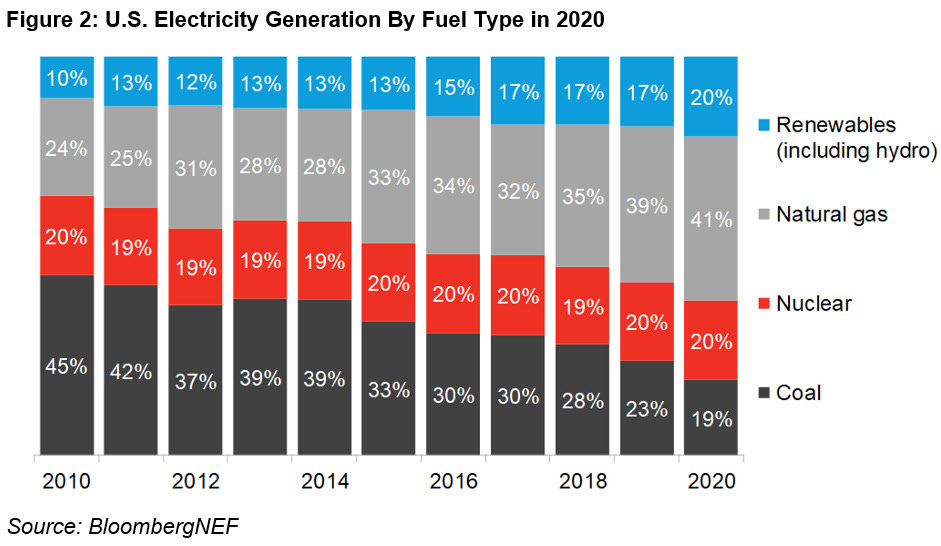

Over the past ten years coal has been steadily removed from the US power system. Natural gas, wind, and solar have feasted on coal’s demise. No, this is not news but it’s handy to see in full, now that we have 2020 data in hand to ponder the decade. The decade to come could be extremely unkind to natural gas. Despite advances from the European power engineering sector that has, to its credit, produced super efficient natgas turbines, it’s just not going to be enough to save NG in the electrical system. Wind and solar are already becoming commoditized. That means only grid level storage or other load-shifting strategies stand in the way. Bet on it: wind and solar and storage are going to do to natural gas what they’ve already done to coal. So, last decade in US electricity was a robust evolution. This decade: revolution. Chart: from the Sustainable Energy Factbook.

It’s a tradition, and an unfortunate one, that climate journalism is nearly always and everywhere about policy. The diminishing returns to such a tradition are going to become more glaring however as we further depart the domain of policy and forcefully enter the belly of transition. Newsflash: decarbonizing the planet will largely be accomplished by groups of humans organizing themselves around competitive technologies and services, also known as corporations. Gasp! So it might be behoove climate journalists to incorporate (hah) earnings reports and growth prospects in key industries to their coverage. Enphase and SolarEdge for example reported Q4 earnings and revenues earlier this month, and their growth was stellar. But here is where climate journalism could make a more notable change: by reporting on the earnings and revenue outlooks that companies provide in their conference calls. Both Enphase and SolarEdge would be excellent targets for such coverage because, of course, they produce all the electronic components to the industry. Explaining to readers, for example, the most salient point—that 40% annualized growth is currently in the corporate forecast—would be a far more insightful data point. And it might help transmit an important message: energy transition is taking place globally, far from the partisan (and internecine) policy wars in US states or Washington, DC. Solar is dirt cheap, and powerful. Monster growth is dead ahead and the companies are explaining to you just how that growth will happen. Now there’s a story.

Just to remind: the Oil Fall series will receive its update sometime this quarter, and will be sent out free to all purchasers of the original title.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.