Revenge Effects

Monday 21 February 2022

Vehicle miles traveled in 2021 rebounded strongly in the United States. On one level this is not a surprise, given the steady progression of job gains and commercial activity especially, as supply chains were resurrected. So strong was the rebound however that 2021 total miles traveled at 3,228.8 billion came within 1.2% of 2019’s 3,269.1 billion. That level of recovery is not matched however by trends in US gasoline demand. 2021 demand has come in at 8.79 million barrels a day vs 9.31 mbpd in 2019, a 5.6% spread. According to EIA, this year’s gasoline demand will rise again, but just to 8.95 mbpd. What might account for the near full recovery in miles traveled, but failure of gasoline demand to do the same?

A suite of factors most likely explains the difference. Although national US adoption of EV remains far behind China and the US, California had a strong year as plug-in sales reached a 12.4% market share. Americans also bought alot of new cars, and despite headline problem of ICE cars more generally, ICE fuel efficiency gains do keep moving forward, albeit slowly. Another factor: trucking activity soared, as did delivery services, and goods delivery in the aggregate is more efficient than individual purchases made on a standalone basis, with consumers making their own trips.

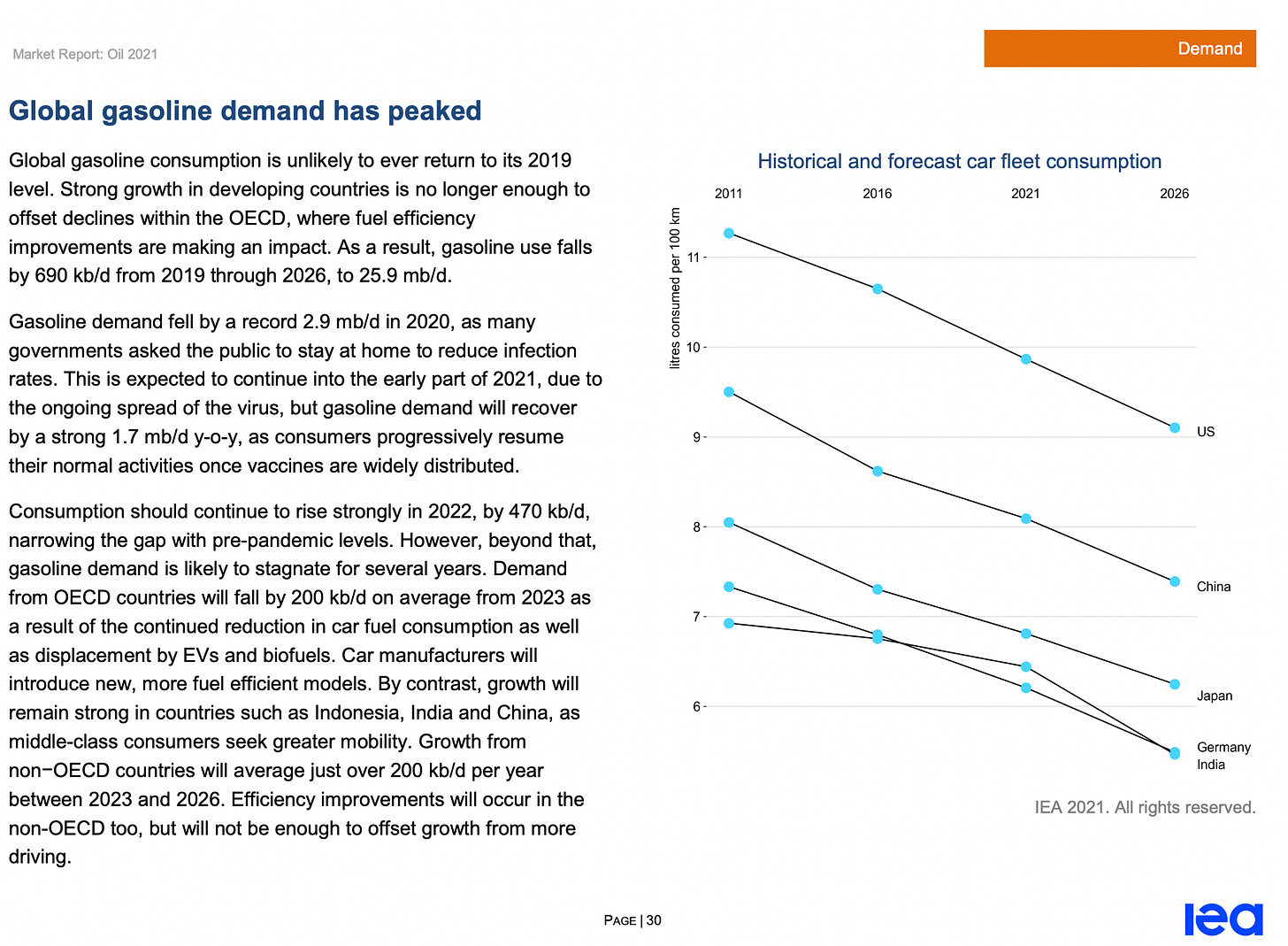

Just to remind, IEA declared one year ago that global gasoline demand has now peaked. Moreover, IEA data shows that China gasoline and fuel oil demand has been flat for four years now (2017-2020). While that demand is forecasted to rise this year, road fuel in China is going to have to overcome a projected 6 million EV sales in 2022.

In the accompanying text to the chart above, note carefully the following framing: Strong growth in developing countries is no longer enough to offset declines within the OECD, where fuel efficiency improvements are making an impact. Readers will recognize this dynamic, identified by The Gregor Letter as the one that now governs global crude oil demand more generally. The industry has survived this past decade largely because flat to falling demand for oil in the OECD has not just been offset, but more than offset, by strong growth in the Non-OECD. That dynamic is now coming to an end for gasoline, and is now set to determine the much bigger path ahead for global oil demand.

The era of avoided oil demand growth from EV adoption has now begun. Based on analysis from The Gregor Letter, the 10 million new EV set to hit the road in 2022 will avoid approximately 445 thousand barrels per day of new demand. This estimate could be higher or lower of course, depending on the mix of both consumer and commercial models deployed, and the average miles-per-gallon of ICE vehicles being displaced, which varies greatly across domains. The calculations were first laid out in the last letter. To paint two extremes: if EV were only being adopted in China, and only in the passenger vehicle sector, where the average gasoline mileage is a fairly high and efficient 40 mpg, then the volume of avoided oil demand would be smaller, until EV adoption reached much higher levels. If EV were only being adopted in the US, meanwhile, where fuel efficiency is much lower, at an average of 25 mpg, then even the front end of EV adoption would start to have an impact. Think: Amazon putting the first and second tranches of 100,000 EV delivery vans on the road.

Let’s play around with the amount of oil that could be displaced in the years ahead. In the chart below, two growth cases are modeled. A rather conservative annual growth rate of 20%, and a more aggressive growth rate of 40%, is applied to global EV sales for the next five years starting with 2023, while also adding this year’s expected sales of 10 million units. Global EV sales grew by 100% from 2020 to 2021, and are expected to grow by 65% from 2021 to 2022. As always, the annual growth rate will slow as we now move into the middle of the adoption curve. The aim here is not to make a prediction of how the EV rollout will proceed with precision, but rather to help readers think about how, from this point forward, it now makes sense to count avoided barrels. Because avoided barrels are going to start adding up rather quickly.

If global EV sales rise just 20% next year, and every year for five years, the cumulative amount of daily oil demand that will be avoided, including 2022’s .445 mbpd, will be 4.415 million barrels a day (3.97 mbpd for years 2023-2027 + 2022’s .445 mbpd). So even in the conservative case, the oil industry is looking at a fairly major loss of demand in the transport sector that it will have to make up elsewhere, via new ICE vehicles still hitting the road, and all other petroleum applications. To put this in context, that’s a solid 4.4% hit to global oil demand using the 100 mbpd baseline which describes current demand levels. Suddenly, the notion that EV will “not have much of an impact on global oil demand” is not just outdated, but can be discarded. Indeed, total global oil demand growth in recent years—say, since 2015—has struggled to exceed 1-1.5 mbpd each year. The conservative EV adoption case starts hitting the market with a loss of nearly half a million barrels a day this year, more than a half million barrels next year, and proceeds to wipe out three quarters of million barrels in 2025.

Those who are not familiar with how commodity markets function will intuitively notice that 100 mbpd of demand is a very big number, and that half a million barrels a day is quite a small number. Let me help: the oil market is everywhere and at all times not about the big number, but rather the going-forward small number. Faster annual growth of 2 mbpd can place considerable pressure on prices, for example. Slow annual growth of 1 mbpd has tended to keep prices stable. Flat growth can grind away on oil prices, but outright declines, even “small” ones can hit prices very hard. If you want to amaze audiences, casually remind someone that the Great Recession saw global oil demand fall less than 1 mbpd annually, from 86.7 mbpd in 2008, to 85.8 mbpd in 2009. The small number, not the big number, drives the market.

While the electrification of global transport is absolutely necessary, it will not be sufficient on its own to trigger quick declines in global oil consumption. If we think of China, for example, as the primary industrial base of the world it’s easy to think of how much CO2 output will remain on the table in China even as their fleets turnover to EV. According to the current IEA forecast, China is on course to consume 15.95 million barrels per day of petroleum products this year, 2022. But after stripping out total projected gasoline and gasoil consumption, the two main road fuels, that still leaves 8.70 mbpd of consumption spread across such categories as ethane, naphtha, jet fuel, and other petroleum products.

We also need to consider the declining efficiency and potentially poor lifecycle emissions from overly large and heavy EV passenger vehicles. It is one kind of calculation for large commercial EV to replace commercial ICE, given the high productivity of that category. Commercial EV like buses, delivery vans, and heavy trucks scoop up trips that would otherwise be undertaken by numerous ICE vehicles, and perform energy intensive tasks that would otherwise call upon oil. But it is quite another to contemplate the displacement of a compact, crossover ICE SUV with something like GM’s EV Hummer. Simply put, once you scale up passenger EV enough, the quantity of material inputs is so large that one begins to slide backwards, on a lifecycle emissions basis.

Back to the EV Hummer: a vehicle so large and heavy that its battery alone weighs nearly 3000 pounds, about the same as an entire Honda Civic. That particular comparison is apt, because over at MIT’s Trancik Lab, you can play around with a helpful and interactive scatter plot that looks at lifetime emissions across a range of ICE, hybrid, and pure 100% electric vehicles. And it must be said: the Honda Civic, an ICE compact, gets very close to a current array of hybrid vehicles in its lifetime emissions. | see: non-interactive screenshot below, that will take you to the MIT site if you hit it.

While the EV Hummer is not scored yet on the MIT interactive, it’s reasonable to expect that its lifecycle emissions will not appear anywhere near fellow EV models, hovering around 200 grams of CO2 per mile. No, passenger EV vehicles like the Hummer are likely to wind up in the black dots, with the other ICE vehicles, above 300 grams per CO2 per mile.

That’s just plain bad, on a number of levels. We’ve just been treated to an American football Super Bowl that was plastered with advertisements for EV. That’s great. But if the US market is going to be enticed to buy very large passenger EV vehicles, then the harvesting opportunity on the level of oil consumption will still be rewarding, but a great deal will be given back in lifecycle terms. And those terms matter. Why? Because all those harder to abate sectors, like steelmaking and mineral extraction—which are due to remain healthy during the long phase of energy transition—will be hit with notable demand growth, undoing much of the work achieved in getting off road fuel.

Fossil fuels, and the world’s dependency on them, are having a moment of revenge. There is no single actor driving this phenomenon; rather, it’s the confluence of existing path dependency in the incumbent system, right as the producers of incumbent energy see all too well the new technology being delivered by energy transition. The revenge effect, therefore, is a kind of emergent property. Global automakers are switching over to the EV platform; global powergrids are full speed ahead in their adoption of wind, solar, and storage; global capital is fleeing fossil fuel investments; and unsurprisingly, global producers of fossil fuels—a class of private and state run entities—are being cautious in how much they invest in further output. And it only adds extra friction to the effect that private oil companies started curtailing their investment in new barrels a decade ago.

So far, The Gregor Letter has tracked the various bad-faith explanations for tight oil and natural gas markets, which have universally blamed the pace of energy transition, calling it “greenflation.” And we’ve also covered the most conventional explanation: that a new era of aggressive fiscal and monetary policy delivered a far faster rebound globally. In past financial crises, industry of all kinds had plenty of time to recover. Not this time. But now we are seeing other voices, some more neutral, and others even on the side of climate action, acknowledging that the world still needs fossil fuels, and for a long while yet, even if in diminishing quantities.

In the UK, for example, the government is openly stating these sentiments exactly. Note the framing, in that twitter thread’s reporting: “Continued support for Britain’s oil and gas sector is not just compatible with our net zero goals, it is essential if we’re to meet the ambitious targets we set for ourselves while protecting jobs and livelihoods,” he (Greg Hands) told parliament. Meanwhile, Blackrock has made strong, conciliatory remarks in just the last week, in an effort (apparently) to ward off threats of being dropped from the Texas pension system. “As a large and long-term investor in fossil fuel companies, "we want to see these companies succeed and prosper," BlackRock executives wrote in a letter that a spokesman confirmed was sent at the start of the year to officials, trade groups and others in energy-rich Texas.

The preview to this theme occurred about one year ago, when the Texas powergrid went down amidst a wave of bitter cold. Politically driven groups blamed the state’s windpower fleet for the disaster. Ironic, really, considering George W. Bush was the original, legislative prime mover in getting Texas to its current position as a wind power giant on the world stage. The problem with this motivated reasoning is that the state’s uninsulated natural gas pipeline system was primarily to blame. And engineers had in fact warned Texas energy policy groups for years that this could eventually be a problem. The real problem: upgrading pipelines costs money.

The development of the term revenge effect comes from Edward Tenner, formerly of Princeton University, who wrote the book Why Things Bite Back: Technology & the Revenge of Unintended Consequences. The central idea is pretty easy to understand. Tenner observes that new technologies do indeed solve problems, but then tend to throw off a new suite of problems. One of his well-understood examples: the computer and electronic-device age has solved many computational and work problems, but unleashed new ones in the form of repetitive strain injuries and the overall negative effects of sitting too long in chairs. Here’s a brief review of Tenner’s original book. (opens to PDF).

What is the revenge effect therefore, that is now appearing alongside energy transition? Well, it’s not that wind, solar, and storage or EV are generating new problems. Rather, it’s their collective advent, and the exuberance by which capital is chasing them, that has highlighted how dependent the world remains not just on fossil fuels, but really fossil fuel systems. The revenge expresses itself therefore in the no man’s land, where we are attempting to free ourselves of the old system, only to receive the answer from that same system: not yet! The incumbent system is biting back, telling us that we will still have to invest enough in that system to prevent it from seizing up. Otherwise, we will have persistent energy cost inflation, which, look out, could interrupt the buildout of new energy technology.

What happens next? More of the same, probably. When you begin to accept and really absorb some of the other facts laid out in today’s letter, you come to understand that the global oil and natural gas industries are going to continue to be very cautious, now that they understand the marginal barrel will increasingly be produced not to serve growth, but to serve dependency. At one point in the near past, British Petroleum produced roughly 4% of the total annual production of oil globally. How eager would you be to invest new dollars in new production capacity if you thought that EV alone (not to mention all other ESG directives) could account for a loss of 4 million barrels a day of demand, between now and 2025?

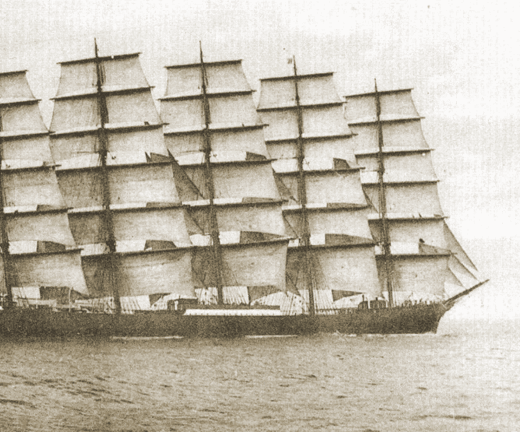

Although unlikely, one avenue that fossil fuels may explore are ways to be more relevant, more efficient, or better priced. You can discern the minor efforts already made towards this goal in projects like carbon capture in coal combustion, super efficient natural gas turbine development, and pledges by oil companies to bring their own daily operations towards net zero. It just makes sense. If you see your industry entering the sunset years, why not try to market yourself better? One conjecture a number of people have made is whether the auto industry, in partnership with the oil industry, may eventually try to develop super high-mileage ICE vehicles as a counterpoint to the high energy efficiency of EV. Cool idea. But it may be too late.

These thoughts were echoed recently by Ethan Mollick, a professor at Wharton. The paper he cites, The “sailing-ship effect” as a technological principle, can be found here.

James Bullard of the St. Louis Federal Reserve is the odd man out. Bullard has a long history of intemperate outbursts, and other efforts whose sole aim is to grab headlines. In the past few weeks, Mr. Bullard has come out swinging for a bigger hike of half a percent in March to get things started, and even hinted at the potential for surprise, emergency measures. But as so often is the case, Bullard received no support from other members of the FOMC in the aftermath of his splashy, market-moving TV appearances. Quite the contrary. Mary Daly of the San Francisco Fed and Loretta Mester of the Cleveland Fed were both quite firm in their intent to fight inflation. But they did so by reiterating past remarks, and Daly in particular cautioned against forming a big, scary plan in advance that could create lock-in. The final blow to Bullard’s view came from the Federal Reserve’s Vice-Chair, John Williams of the New York Fed. In remarks made just this Friday, Williams pushed back quite specifically against the idea that one has to kick off the rate hike cycle with a big bang. From the linked article:

“There’s really no kind of compelling argument that you have to be really, you know, faster right in the beginning” with rate moves, and “I don’t see any compelling argument to take a big step at the beginning,” Mr. Williams told reporters after his formal remarks. The Fed can instead nudge rates up and take stock of how the process is going, he said.

What many Federal Reserve members have quite clearly confirmed is that the rate hike cycle officially begins in March. And now we know it will begin with a quarter point hike. We still have one more CPI reading to get through, however, between now and then. And the details on that CPI reading will matter alot. The last reading, at 7.5%, was ugly. What markets are clearly looking for is some sign not that inflation is about to dramatically decline, but rather, that inflation has peaked.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.