Revenge of the Fossil Fuels

Monday 23 December 2024

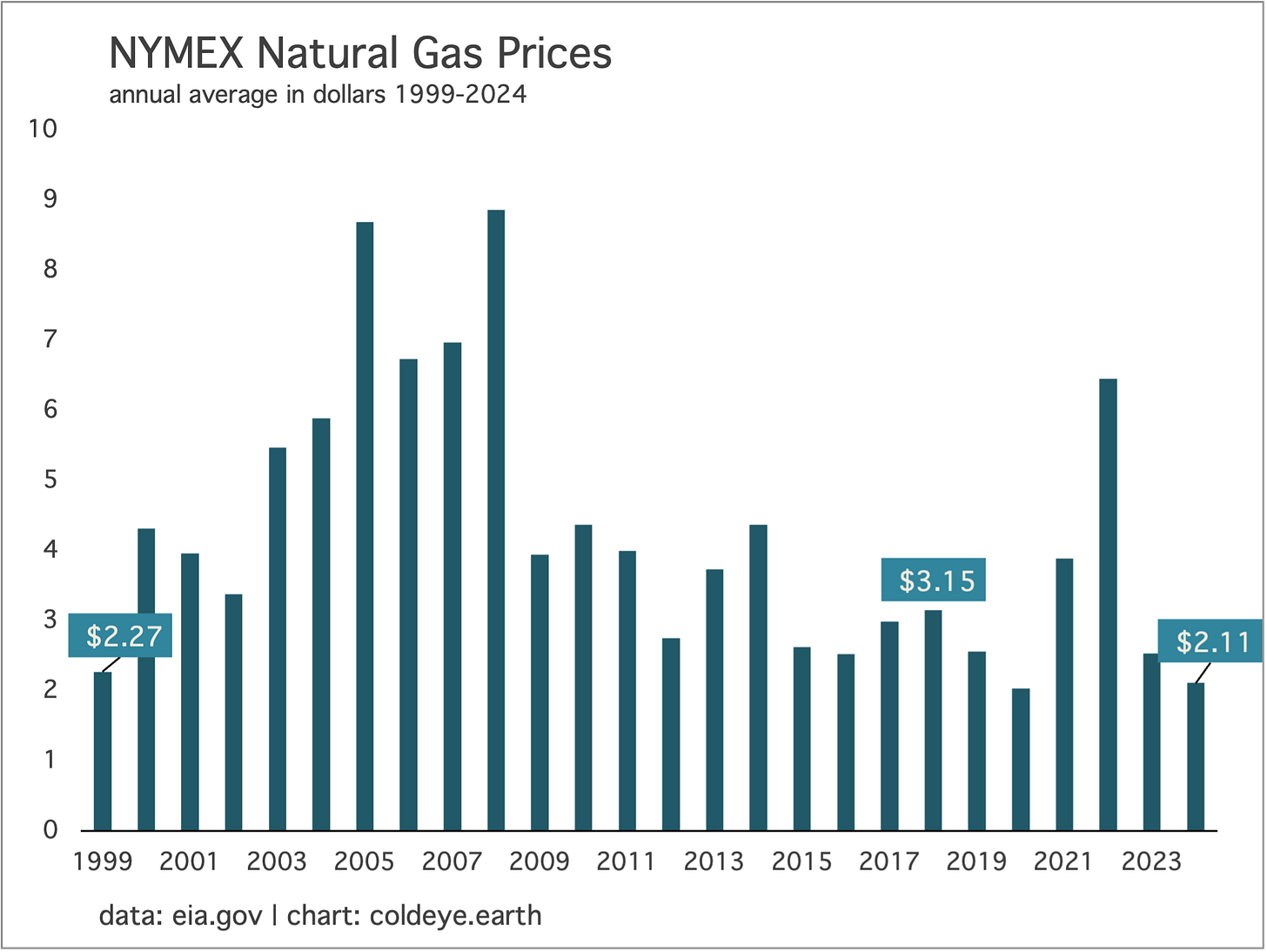

Natural gas prices are so low they should be making headlines. Just how cheap is American gas these days? Imagine walking into a supermarket this week to buy last minute items for Christmas and discovering that everything has been marked down to prices last seen in 1999. Yes, that cheap. The average price for a million btu of Henry Hub at the NYMEX has averaged $2.11 through the first 11 months of 2024, and in 1999 that same figure stood at $2.27. These are not outlier prices either. In 2018, when most would agree the economy was quite strong, the average annual price was $3.15. In the past decade, the outliers have been the high prices for natural gas, not the low prices.

The reason 1999 supermarket prices would feel like a bonanza is that the purchasing power of your wages would have certainly gone much higher in the intervening 25 years. Using the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator, natural gas at $2.27 in 1999 would require $4.27 in today’s dollars because today’s dollars buy so much less of everything. While the price of NYMEX natural gas bounces around alot (here in December 2024 it’s currently trading above $3.50) the average price this year of $2.11 means that unlike most other prices on the planet, natural gas has entirely failed to keep up with inflation. Lucky you.

Energy transition was fated to eventually have a showdown with very cheap fossil fuel prices. Now it appears that in addition to cheap natural gas, we have a new problem arising with coal. You will recall that global coal consumption peaked in 2013-2014, very gently declined for 7 years into the low of 2020, and then rebounded strongly in 2022 to match the old high—and then, in a final flourish, proceeded swiftly to make a new all time high in 2023. Ouch.

If that was not shocking enough the IEA just reported coal made yet another new all time high this year, with demand growing a full 1.00% and will not decline at all from this level over the next three years! From the lede of the report:

Coal is often considered a fuel of the past, but global consumption of it has doubled in the past three decades. At the height of lockdowns related to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, demand declined significantly. Yet the rebound from those lows, underpinned by high gas prices in the aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, has resulted in record global coal production, consumption, trade and coal-fired power generation in recent years.

Notice the interplay of price and demand referenced by the IEA: when natural gas gets expensive, coal gets cheap by comparison. It can work the other way too, when cheap natural gas from the US is exported through the LNG channel—exactly what happened in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine, causing coal prices to spike. But now, global coal prices (Newcastle, for example) have given back 100% of the 2022 spike and coal once again is dirt cheap. All together, this is clearly why the IEA dares not forecast any coal consumption declines for the three years of 2025 through 2027.

For those foolish enough to predict peak emissions in China (hint: this can’t be done, so anyone claiming they can make such a prediction is telling on themselves) the IEA seems to have carved out a special warning:

A third of all the coal consumed worldwide is burned in power plants in China, making the country’s electricity sector the main driver of global coal markets. In 2024, China has maintained its focus on diversifying its power sources, continuing to build out nuclear plants and accelerating its massive expansion of solar PV wind capacity. The country’s hydro sector also experienced a rebound after several years of underperformance. However, electricity demand in China is increasing strongly, growing at a faster rate on average than GDP since 2021. Two major drivers are underpinning power demand growth in China: the electrification of services previously provided by other fuels, such as mobility and industrial heat, and emerging industries such as data centres and AI.

This bewildering decade-long journey of global coal demand should be highly persuasive of the following points:

• Stellar growth of renewables is a necessary but insufficient method to decarbonize powergrids.

• If it’s impossible to model global coal’s confounding pathway from peak, to decline, to full resurrection over a 10 year period, then one has no chance at all of modeling or forecasting peak emissions.

• The vast surplus of Asian coal-capacity is an ever-present Sword of Damocles hanging over energy transition because economic growth, and weather extremes, can put that capacity into play anytime—and this is precisely what’s happened.

• If you find the global adoption of electric vehicles exciting, just remember that if marginal powergrid demand growth from EV is not covered by renewables, it will be covered by new natural gas and existing coal. Note also that the IEA cites data center growth and AI as new drivers of power demand, alongside EV, in China.

• Vehemently anti-nuclear voices who’ve declared for years we only need wind, solar, and batteries to decarbonize have decisively lost their argument.

If you were a President coming to power in the United States, how would you guide policies around the use and export of natural gas? And in particular, what if you didn’t care even a little about emissions and climate change? As a new administration prepares to take control in less than 4 weeks time, the US remains a giant of fossil fuel production, and a significant exporter of bountiful surpluses in coal, petroleum products, and natural gas via LNG. Here are two directions the US could take:

• Continue to exploit the competitive advantage offered by cheap, domestic natgas for the sake of the country’s industrial base. Indeed, if we combine both industrial and commercial sectors, together they account for over 40% of the country’s total natgas consumption. A fossil-fuel forward administration might even create incentives to boost domestic consumption further.

• Increase natgas exports further by twisting the arms of allies like Europe to increase LNG imports from the United States.

The US has already significantly increased LNG exports in recent years, because the country can offer that product at such competitive prices. And of course, the US has surely been enjoying for a decade now the ultra-cheap natural gas available to us through domestic production. Comparatively, however, the advantage conferred to a $27 trillion economy through the exploitation of a very cheap energy source far outdistances any boost from LNG exports. Let’s talk about that.

The export of raw commodities is typically associated with less developed nations. There are exceptions. But generally, it’s preferable to add value to these exports. Less developed countries therefore dig up coal and copper and other natural resources, and send them straight to the ships because they lack the infrastructure or level of development required to add value, and increase profits. A business economist pointed out these themes to your correspondent many years ago, as we stood on a hill high above Wellington Harbor, in New Zealand. For a long while we watched a large ship loading raw log lumber into its hold, and all the business economist could do was shake his head, and decry it. “Raw logs! What the hell are we doing exporting unfinished lumber?”

According to reports, the incoming administration absolutely loves the idea of increasing raw commodity exports and intends to browbeat our allies into buying more LNG. Trump has now said explicitly that the EU must buy more oil and gas to reduce its trading imbalance with the US. But the potential delta—between what we’re already exporting, and what we could export to the EU—is small, if non-existent. The EU has already increased LNG imports from the US, after decreasing its reliance on Russia. Indeed, there’s a much larger dynamic at play here: EU consumption of oil and natural gas is in decline.

Global fossil fuel consumption in the aggregate has risen again in 2024 to a new all time high. The IEA has estimated that natural gas will have grown by 2.5% and, as discussed already, coal use grew by 1.00%. Oil remains the weakest grower of the bunch, with various estimates coalescing somewhere around +0.8% for the year. Together, this allows for an estimate of the year’s aggregate increase. Using trailing data from the EI Statistical Review, the aggregate fossil fuel increase for the year stands at +1.35%.

Notice how the respective, estimated increases of each fossil fuel mostly aligns with the threat they each pose to getting global emissions under control. The world is actually doing a decent job constraining oil growth. The persistence of coal and its stubborn refusal to decline is both bewildering, but an important factor in holding emissions firm at a high level. The most serious threat however now comes from natural gas. Oil and coal live on these days mostly in the pre-existing infrastructure from the 20th century. Natural gas however is going through a new and massive adoption phase, with new gas-fired power generation being built everywhere.

Cold Eye Earth is well aware that readers prefer good news. But good news on climate progress is simply not on offer, right now. The world will have built an absolutely crazy volume of new wind and solar by the time the year ends, but demand growth for power will still way outdistance that fresh supply. Look at coal. Look at natural gas. Meanwhile, climate coverage has fallen into a rut, repetitively counting up renewables growth to produce its next news article, but forgetting or perhaps neglecting to confront the fact that this is only half the story.

The proliferation of peak emissions calls meanwhile—a phenomenon which has really gone into overdrive the past few years—is both irritating and unhelpful, but can be interpreted as a form of frustration. Because no one possesses a method to make such a call, the merchants who produce these reports—whether peak China emissions, peak global powergrid emissions, or peak total emissions—all share the same reasoning: surely, after so much renewables growth, fossil fuels must be near their terminal growth phase. The approach fails of course because economic growth itself, in addition to the economics of existing energy infrastructure, are still in control. As Cold Eye Earth is fond of saying: a small thing growing fast is an amazing sight to behold—but a large thing, growing slowly, can be truly fearsome. Reporting on the small thing, but neglecting the big thing, is no way to conduct responsible coverage.

Energy transition, therefore, has renewables growth working in its favor, but economic growth itself as a competitor. If we acknowledge the tendency of economies to grow, then the only plausible offset to this competition is to pair forced retirements of fossil fuel infrastructure with renewables growth. Yes, if you follow the curves far enough, legacy fossil fuel systems will eventually retreat on their own. But as explained in The Underlayer, this is not happening now. The fossil fuel underlayer is sturdier, more robust, and younger than ever. The amount of new natural gas capacity that’s been built in the world the past 15 years is a shocker—and the United States has taken a leadership position in that buildout.

When we consider the year 2025, and the position we currently occupy in the energy transition, we might say that renewables growth has been stronger than even many of the optimists expected, but the intractability of legacy fossil fuels is far nastier than expected. The path that energy transition has followed so far is the soft-impact route, which seeks to avoid upsetting consumers with restrictive disincentives. This makes so much sense as the first journey out of the morass. However, unless you want to wait for those lengthy curves to play out, populations are going to have to be inconvenienced by an accelerated and forced retirement of good working assets, everything from power plants to cars.

And that’s not likely to happen, of course, because it’s hard to impossible to get elected on such a platform. On the brink of a new year, therefore, let’s try to remember that no matter how many new GW of wind, solar, and batteries that get built next year, and no matter how many coal plants retire, or EV adopted, economic growth and aggregate demand only needs to expand normally to keep the bulk of existing energy delivery systems fully functioning, and ready to serve.

We have reached therefore not a take-off point as many had assumed, but rather a stand-off. To break that stasis would require a dramatic course correction: the OECD building nuclear on a pace that overthrows current regulation; retirement programs for petrol-based vehicles that are costly; or a moratorium on new natural gas capacity, with a mandate to build renewable+battery powerplants instead. Political economies from Australia to the US have no doubt considered these choices, and understandably decided not to pursue them. And there you have it.

—Gregor Macdonald