Rollover

Monday 30 May 2022

A trend change is taking place in the US interest rate environment that, if sustained, will shape the economy’s path forward into year end. The shift comes as many markets finally succumbed to the Federal Reserve’s rate hiking cycle, all cracking lower over the past six months. Rates are of course both a reflection of conditions, but also act as an agent of those conditions. After dramatic declines in stock markets, bond markets, crypto markets, and now housing markets, interest rates have pivoted lower after surveying the wreckage and have perhaps come to a conclusion: The Fed is starting to gain real traction against inflation. Indeed, recent readings of inflation, like Friday’s PCE data, strongly suggest that inflation has now peaked. Core PCE for April came in at 4.9%, down from 5.2% in March, and 5.3% in February.

Memories of the protracted inflation of the 1970’s, while faint due to time passing and generational turnover, continue to influence observers of the US economy. But that era is unlikely to offer satisfactory clues to the inflationary potential today, either in the US or around the world. The global economy today is highly automated, optimized, and networked. The pandemic snarled and whipped those attributes into a tangled mess but alas did not break them, or erase them. There is no question however that the US economy ran too hot in 2021. But equally, there is no question it’s slowing down, and may be rapidly slowing down, in 2022.

The pivot in interest rates can be observed several ways. First, as highlighted in the last letter, Federal Reserve members began to make slight adjustments to their public remarks starting several weeks ago. We might list these as follows. 1. Powell at the 4 May FOMC presser pointing out that interest rate markets had already done alot of the tightening. 2. James Bullard, surprisingly asserting that the Fed was no longer as far behind the curve as many think. 3. Other Fed members like Bostic and Daly, saying once again that a 75 basis point hike was not necessary and not on the table. And then in just the past two weeks: 5. Bostic saying not once but twice that after the June and July FOMC meetings, where it’s anticipated the Fed will hike 50 basis points at each, that it may be time to pause, and be open to how the September meeting might go.

You can also observe the rollover of rate expectations in the behavior of the 10 Year Treasury yield, the 2 Year Treasury yield, and the US Dollar Index. The latter two instruments have sent a fairly strong signal. Note the extremely steep angle at which both ascended over the past 7-8 months, and now the rollover from the peak.

The second chart, of the US Dollar Index, is especially telling because it records the opinions of the global financial markets as to whether interest rates in the US are still poised to go higher, relative to the rest of the world. For now, their answer is a fairly resounding no.

As cracks have started to appear in the US economy—tech companies like Amazon saying they’ve done enough hiring for now, retailers seeing a big slowdown in purchases and a rise in inventories, used car prices declining, and mortgage rates soaring alongside an unsurprising slump in the US housing market—it can be helpful to also check in on sentiment. While not scientific, I ran the following poll on Twitter just over one week ago. (you’ll need to click on the tweet to see the results). Needless to say, the fear of higher interest rates likely peaked, as it always does, right as rates probably peaked as well.

Rates also appear to have peaked just as fear itself has transitioned from a focus on inflation, to a focus on growth. There is justifiable concern that the tightening cycle meaningfully raises the risk of recession. But the uncertainty is how near in time we would be to such an outcome. (Of course, the US labor market is not even close, not even a little, to a recession).

There is still an optimistic path forward. There are monthly macroeconomic reports to come on inflation, jobs, and industry both in June and July. If inflation continues to fall, and growth continues to weaken, then the outcome already being hinted at—a pause in Fed rate hikes—will materialize quickly. And this will be known in just eight weeks time, by the end of July. If the ever elusive “soft landing” were to materialize, this is a rough roadmap to how it might look: a rap on the knuckles of demand, interest rates falling, mortgage rates falling, inflation falling, but stock markets rising, opening the door to a new, nascent strengthening phase or perhaps a consolidation phase in the US economy as inflation continues to drift downward.

EV market share is starting to operate like a ratchet, doing well when vehicle markets are strong, and doing even better when vehicle markets are weak. Let’s begin with the laggard market, the United States, which is finally sending out a new signal. After languishing for years around the 1-4% market share level, EV sales in the US have started moving more regularly above the key 5% threshold. In fact, 2022 data shows that EV share hit nearly 6% in December, approached 5% in January and February, then soared to nearly 7% in March. The reasons are not complicated. Petrol prices are high, model availability and consumer choice have improved, and the US car market is weak. The chart below comes via EV Hub.

Meanwhile in China we are seeing very much the same story in 2022. China of course has suffered a major industrial slowdown in Q2 as it once again battles the pandemic. This has impacted the country’s oil demand, and especially vehicle sales which have slumped hard. EV sales have been hit also, and as a result, may not make it to the 6 million mark many had originally forecasted for this year. But market share continues to soar. Through the first four months of 2022, EV share has climbed from 13% last year to over 20%.

Because of the pandemic’s resurgence in China, it is best to pull back from any 2022 forecast as to how the year will finish. Accordingly, the 2022 total sales figure of around 23 million, with 4.7 million of those units being EV, is really just an annualized projection based on the latest data. The rest of the year is highly uncertain, in both directions.

Finally, just a quick look at a key European market: the UK. Figures just released by the Department for Transport indicate that EV reached a 14.2% market share last year, as 327,000 units were sold in a total market of 2.3 million.

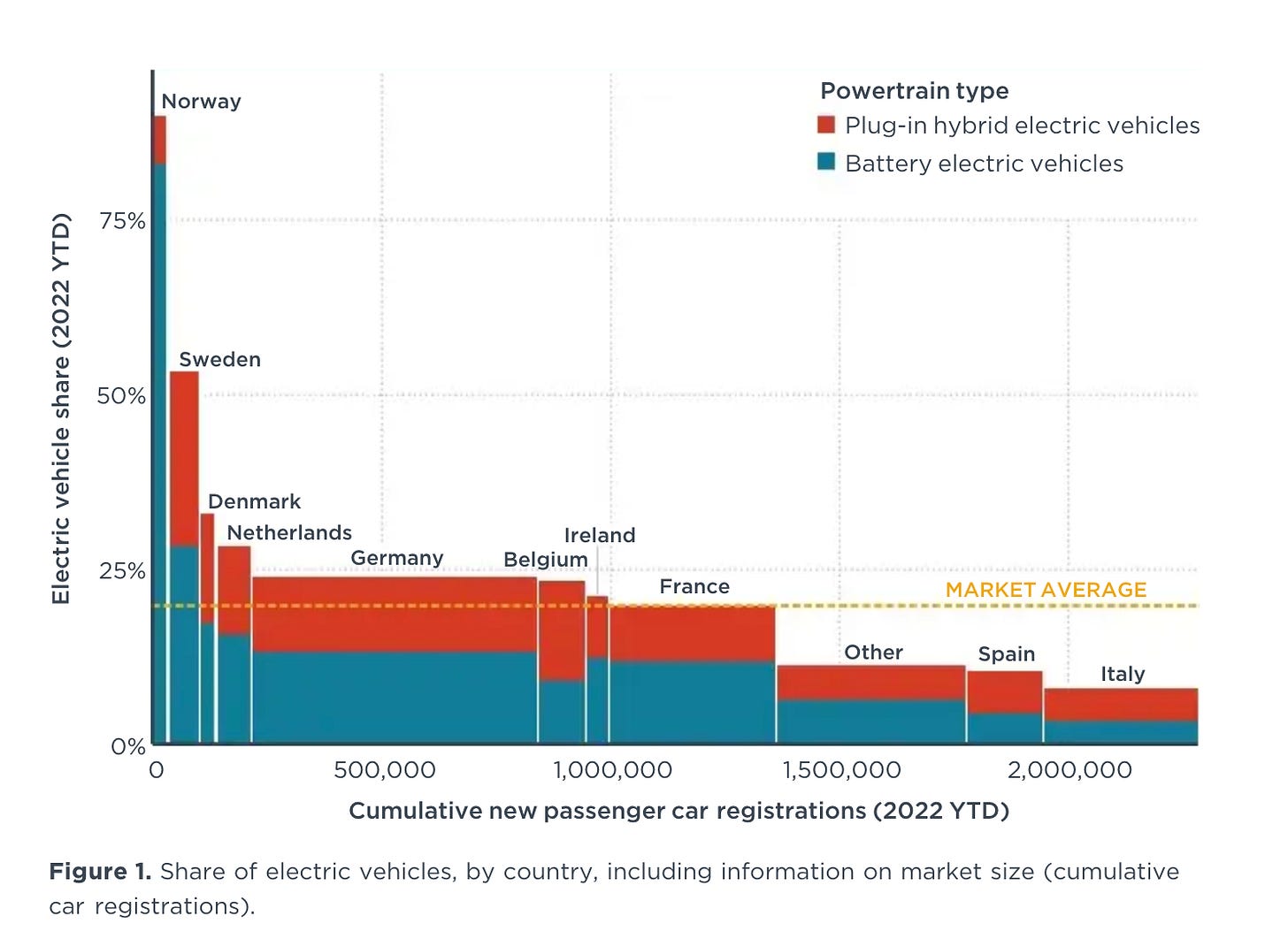

More broadly, some European markets are starting to portray what an all EV market might look like as EV share in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands soar above 25%. And the rest of Europe is also starting to move quickly. In the chart below, which comes from the ICCT, sales figures and market share are covered for Q1 2022. Note the ICCT’s market average line, showing that EV market share in Europe as a whole is already advancing towards 25%.

The volume of avoided annual oil demand, as a result of the burgeoning EV fleet, is now substantial. According to BNEF, the existing global fleet of all electrics (not just EV cars but buses, trucks, and two/three wheelers) avoided 1.5 mbpd of oil demand last year. If we add the basic calculation offered previously by The Gregor Letter, we can incrementally add each year at least 0.45-0.50 mbpd of avoided demand using the current adoption growth rate of global EV. But this would slightly understate the current annual impact going forward, because The Gregor Letter doesn’t attempt to model growth of electrics outside of vehicles. As one example, the two and three wheeler fleet of India is so massive that it regularly accounts for at least half, and sometimes as much as 60%, of India’s road fuel consumption. And this fleet is starting to turn over to electrics.

Global demand growth for oil this year, meanwhile, is not going well. Both EIA and IEA have cut their full year estimates twice now—bringing growth down from a high of 3 mbpd to 1.8-1.9 mbpd. That’s not enough. The Gregor Letter firmly holds the view that this will be chopped down again to 1.0 mbpd of growth, at best. And given the slowdowns in China, the EU, and now the US, the outcome that’s more likely is that no growth defines the year once we finish. Put another way, for the world to see more than 1 mbpd of demand growth this year, the global economy would have to reaccelerate. Maybe that happens. But the world economy will have to stop slowing down first!

As you look at the chart, therefore, 2022 demand is likely to complete the year around 98.50 mbpd, or less. Not the current 99.37 mbpd. That would represent a 1.9% decline from the 2019 high. What data might suggest that outcome? Let’s look at US oil demand so far, through the first four months of the year. According to just released EIA data, 2022 US oil demand is tracking at 1.87% lower than the comparable four month period in 2019. (Just to remind: 2019 remains the baseline year in most data series, given the outlier pandemic year of 2020). And consider that the US economy is undisputedly the strongest in the world right now! If the US is tracking at 1.87% below 2019 levels, how will full year 2022 global oil demand make much progress this year given hard slumping vehicles markets, the China slowdown, and the emerging recession in the EU? Now add the most obvious factor of all: stubbornly high prices.

It’s not clear at all that either established energy sanctions against Russia, or proposed energy sanctions, are effective. The Gregor Letter speculates that researchers in the years ahead may conclude that such sanctions did great harm to the economies of the OECD, while adding very little extra deterrent or damage to Russia beyond the original sanctions regime. The key factor in these trade-offs is the following: whether placing a cloud over 10% of the world’s oil supply actually induces a large enough risk premium on oil prices that it negates the original intent of such sanctions, through a far higher realized price windfall to Russia. And, far greater damage to the economies of Europe, and the US.

To review: Russia is currently trying to operate under an extremely punishing sanction regime that has introduced supply-chain chaos to its industrial base, put up nasty barriers to trade and financial flows, and as a result is wrecking its economy. In the same way Russia is having difficulty resupplying its military, it is lacking in parts and supplies for every industry from aviation to oil and gas production. Without any extra sanctions on Russia’s energy exports specifically, its output would be fated to decline and is declining already. Matt Klein, at The Overshoot, has been updating the situation and Russia’s fortunes are deteriorating rapidly.

Europe meanwhile is supposedly in the middle of a conversation about taking a stronger stance, perhaps a full embargo, of Russian oil and gas. But consider the impact these efforts have had already: natural gas prices have been sky high in Europe, which has had a major impact on its own industrial base. LNG volumes from the US to Europe have soared but this has triggered a huge upward repricing of NG in the US itself, with prices reaching over $9.00 per million btu this past week. And oil prices meanwhile remain improbably elevated.

A group that is strongly advocating for Europe to move to a full embargo has produced a number of papers on the subject, hosted at Stanford. Their paper, “Energy Sanctions Roadmap: Recommendations for Sanctions against the Russian Federation” (May 2022) offers up a rather complicated tariff scheme by which sellers of Russian oil and gas would retain some portion of sale proceeds, for the benefit of Ukraine either now or in the future. But the paper falls down in two ways. One, it makes no assessment as to whether the scheme would work, or why sellers of Russian energy would enter into such a scheme, or any example of how such schemes have worked in the past. Worse, the paper doesn’t address at all the market impact of such schemes, makes no projection of how this would affect global pricing of oil and gas.

Without a direct confrontation of 1. the damage to the world economy from such sanctions and 2. the risk premium pricing that such sanctions would both effect and sustain on oil and gas, it is hard to treat such proposals as anything other than political theorizing. Just to remind: The Gregor Letter takes a strong moral stand against Russia in this affair, has embraced the original sanction scheme, and has even gone so far to suggest that direct military action against Russia on Ukraine soil might be warranted if not preferable because the prospect of Russia’s genocidal intent cannot be tolerated. Just to update this view: while actions taken by the West so far are laudable, the West may already be putting its security at risk in the future because it has concluded (as with past Russian acts of aggression) that the safer path lies in indirect confrontation. But Putin has made it clear he cares as little for Russian lives as he does for Ukrainian lives. And history is pretty clear that when you are dealing with a political leader like that, they will never stop. Until they are stopped.

Just to embrace and extend previous commentary made in The Gregor Letter since the Russian invasion: The OECD should absolutely undertake a kind of WW2 war effort to withdraw from fossil fuels through the deployment of wind, solar, storage, transit, while also making heavy attacks on the demand side too. Shocking markets with future infrastructure plans is a far superior strategy than trying to go cold turkey from fossil fuel dependency. Here’s why: the latter is nothing more than self-harm. The former harnesses markets and capital, sends a signal to the future direction of the energy landscape, and would further deter investment in fossil fuels. To its credit, Europe and the US have struck out into this territory. But you need strong economies to get off fossil fuels. You need forward motion. You need momentum.

The New Yorker has published a very embarrassing article asserting that the cash piles which big technology firms place in the banking system are used to fund fossil fuel extraction, thus entirely countering their ongoing efforts on decarbonization. This is of course a sophomoric idea, that emerges from a kind of naïve inspiration:

If you happen to read the “report” the article covers (and I frankly don’t recommend wasting your time, unless you’re currently in surplus) you’ll find that it’s not really the product of research, but is really just a wild claim, tarted up as research. Just to say, every human endeavor that is financed—from Elon Musk’s effort to buy twitter, to the construction of a new semiconductor fabrication facility—draws on the capabilities of the financial system. And your dollars, and my dollars and the California Public Employee’s Retirement fund’s dollars kept in the system are part of that process. Based on the logic of the report, that the dollars of Amazon, Facebook, and Apple are also used similarly, we can make the following counterclaims:

ExxonMobil’s capital in the system helps fund the buildout of wind, solar, and storage.

Nancy Pelosi’s personal wealth in the system helps fund the manufacturing of guns, low-mileage SUVs, and chemicals.

Harvard University’s capital in the system helps fund the construction of mini-malls, which lease space to nail salons and burger joints.

Capital is water. And capitalism is a water system. Corporate treasurers keep their company’s cash in short-term financial instruments, often t-bills and notes. And those instruments then act as part of the system’s capital base. There just isn’t an immaculate way to run a capitalist system, while segmenting out particular uses of capital from the broader, myriad uses for capital. It’s silly to even have to say it.

But let’s be constructive, for a moment. What if the US government created green versions of its treasury instruments, at various maturities? And what if corporations had the ability to place their capital in such instruments, and such instruments were then used by green banks as the base on which they make particular kinds of loans? Despite the unserious foray into “capitalism” in hopes of finding actual climate solutions, it’s probably the case that western owners of capital will find ways, in the years ahead, to ensure their wealth bears down more comprehensively on the problem.

—Gregor Macdonald

Correction: The original email version of this post, in the last line of the first paragraph, mistakenly attributed February’s core PCE reading of 5.3% to April.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.