Signs of Progress

Monday 26 December 2022

We should be both sober and enthusiastic about the latest advance in fusion. For a brief moment, and at a very small scale, scientific breakeven energy was achieved in a fusion experiment at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Lab, in northern California. The good news: a new stopwatch has started running, marking this moment as the start point on the journey to applied fusion. The sobering thought: commercial application of fusion is probably not just far away, but exceedingly far away. The respondents to this poll (below) are therefore likely correct, in that they chose quantum computing over fusion:

The US Post Office will overweight EV in a large purchase order for new vehicles. You may recall the USPS moved initially, at the tail end of the Trump administration, to purchase mostly ICE vehicles to replace a portion of its aging fleet. The new administration headed off those plans, and now we have reports that an order package for 106,000 vehicles will fall roughly into a 60/40 configuration of EV/ICE:

If you are feeling disappointed that USPS is not ordering 100% EV, it’s worth remembering that a significant remit of the post office is to deliver to rural areas, and west of the Mississippi that means a lot of miles to cover. The likely path for the USPS vehicle fleet, which in total reaches nearly 300,000 vehicles of many types, is that electrification will unfold similarly to the broader adoption of EV: cities and suburbs first, and then rural areas later, if not much later.

We are finally seeing long needed data improvements in coverage of the US electric vehicle market. Historically, US EV sales data has largely been dependent on industry groups or independent data gatherers. Typical examples would be the California New Car Dealers Association (on which The Gregor Letter has depended for years), or myriad blogs that scrape automaker reports to estimate sales. Now, things are changing.

The State of California now maintains both ongoing sales data, and aggregate sales data, for EV within the state. Soon, The Gregor Letter will switch reporting to this data series. More importantly, the DOE’s Argonne Lab, an excellent resource for energy analysis already, is now providing very extensive EV sales data for the entire US market, and has also produced historical data going back as far as the year 2010.

News Briefs • Redwood Materials, run by former Tesla exec J.B. Straubel, has announced it will construct a $3.5 billion battery recycling plant in South Carolina. • Market rent increases may have started slowing before the Fed’s hiking cycle, and are losing their momentum further as the rate of job growth, still positive, decelerates. • Researchers at the Cleveland Fed have released a new housing data tracking index, one that attempts to improve upon very outdated methodology historically used to gauge inflation. Economy watchers are excited about the new data series. • Grand Central Madison, a new terminal adjacent to the original Grand Central, will now handle traffic from the Long Island Railroad. The largest new station built in the US in the past 67 years will allow for faster timetables, and fewer delays, as the new capacity will partly untangle service from Metro North trains. • Air pollution has fallen 30% in Barcelona over a period when the city has aggressively pared back the travel freedoms of the personal automobile. • Michael Liebreich, formerly of BNEF, has released his latest long essay on hydrogen. • Ethan Mollick, the Wharton professor quick off the mark to deploy Open AI’s ChatGPT in his classroom, released a white paper offering guidance on how best to use ChatGPT as a kind of companion, or work helper. Elsewhere, Mollick summed up his views in a HBR essay. •

Subscription rates for new subscribers to The Gregor Letter will rise modestly, starting in January 2023. Individual rates are moving from $7.50 per month and $75.00 per year, to $8.00 per month and $80.00 per year. The institutional rate will move from $300 per year to $320 per year. Also: Every paid subscription comes with a free copy of the Oil Fall 2018-2023 package. Just to remind, no existing paid subscriber will ever see their rates rise, as you are locked in at the rate when you joined. Hopefully, the modest increase will alarm neither readers, nor the Federal Reserve, as the increase is below the recent rate of inflation. :-)

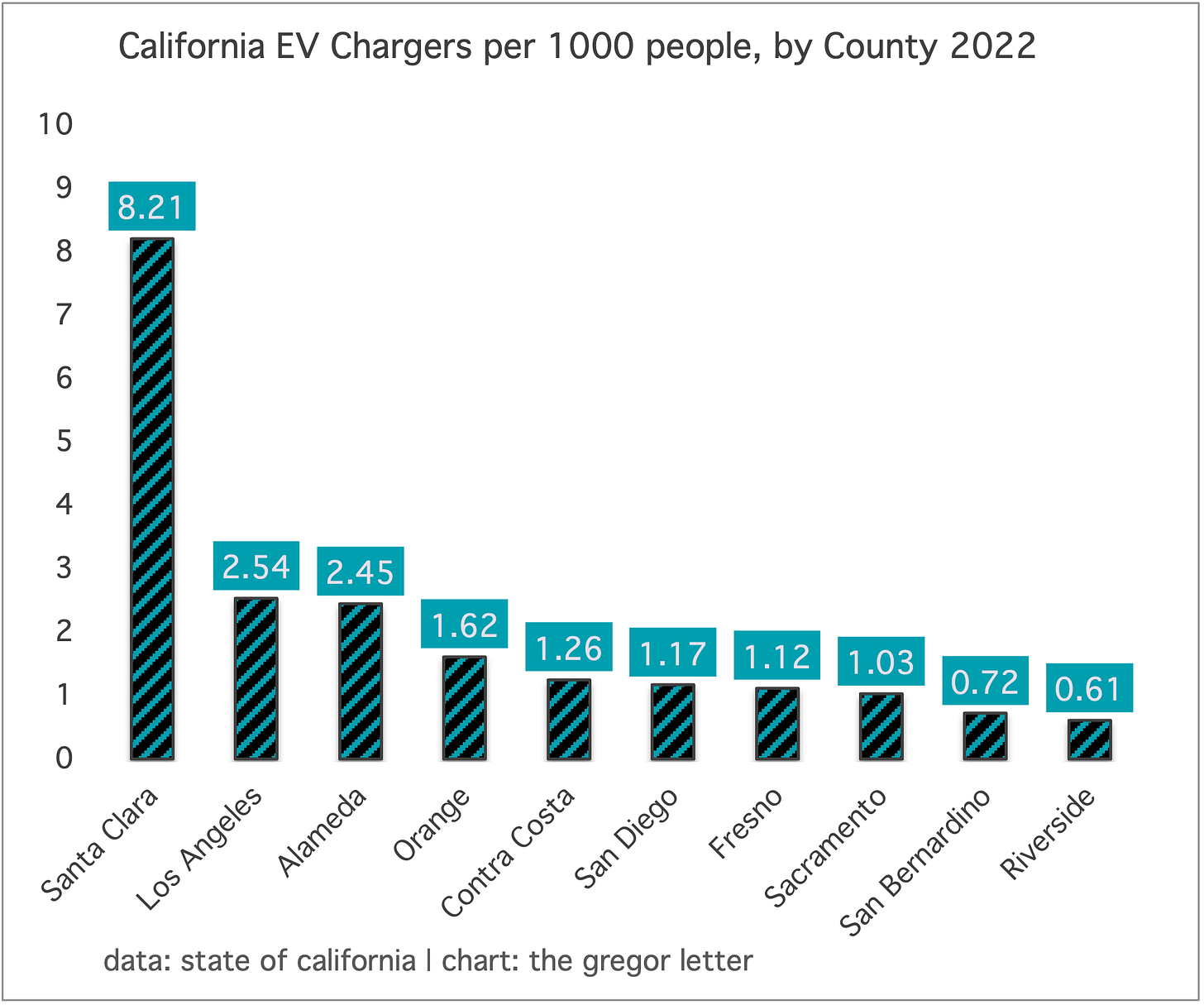

The hand-wringing over the buildout of needed EV chargers never quits. And that’s a shame, a real waste of time. Of all the challenges associated with the electrification of transport, building out charging infrastructure is anything but herculean. General rule: charging follows EV penetration. In the chart above, which shows EV chargers per 1000 people of population by California county, you can see that counties like Santa Clara and Alameda in the Bay area, and also Orange and Los Angeles, are unsurprisingly well ahead of the curve. The ten counties highlighted here are the most populous, in the state.

What would be a good benchmark, though, to project the number of chargers ultimately needed? That’s a trickier question. A couple of things: first, chargers are not charging stations. Data is new and emerging here, and some of the chargers in this data do have multiple outlets, but probably many do not. Again, the survey here is for chargers, not charging stations. Conversely, a petrol station with just two pumps can no doubt fulfill the needs of more cars in any 24 hour period than a charging station could with two chargers, for the obvious reason that gasoline pump-time is around 5 minutes or so, and charging time is much longer. Bottom line, we are going to need more charging stations than petrol stations.

But not necessarily alot more. The total number of petrol stations in California that provide gasoline may surprise you. In a state of 39,240,000 people (2021), California currently has just 8000 stations that dispense gasoline. That means total state gasoline stations clock in at just 0.20 per 1000 people. Interestingly, California petrol stations are declining, from a peak near 8500 in 2016.

But the number of EV chargers we will need is moderated by the growth of home charging. The charger count used in the data series and chart above combines both straight public, and also shared private, chargers. A good example of the latter would be a charger bank in a corporate or university parking lot—not open to the public, but in heavy rotation among employees.

People have an intuition that chargers need to come first; only then can we deploy the EVs. But that’s not how it worked in the petrol-car era, and it’s not likely to work that way this time around. To be sure, governments will need to take the lead policy-wise with transmission infrastructure—an example being dedicated high-speed lines that follow interstates. But mostly, EV charging capability will grow organically in steps, with demand sometimes outrunning supply, and then supply sometimes outrunning demand. Don’t worry. Be happy.

The pandemic is now slipping into the rearview, leaving a lot of disruption, and some grandiose theories in its wake. It’s natural for a crisis to spark the imagination. Soon enough, dawn-of-a-new-era thinking begins to dominate. This was true after the great financial crisis, and it’s true today. Perhaps, surprisingly, even more true. For the pandemic arrived when a number of big wheels were already in motion. And that’s why several post-pandemic ideas seem extra weighty. Their antecedents all began years before, last decade. And now the crisis and its aftermath are given the credit.

A couple of demographic facts are worth mentioning. It’s estimated that the 2020 coronavirus has been responsible, using excess death methodology, for about 16-28 million deaths. That’s terrible, and awful, and sad in every way. Those are big losses, and each one has no doubt rippled across families and communities. The 1918 influenza caused the deaths of at least as many, with estimates running as high as 50 million. But world population was 1.8 billion in 1919, and stood at 7.8 billion in 2021.

Perhaps the biggest regime change now identified as a post-pandemic phenomenon is inflation. Or really, scarcity. In ways called out and claimed, but never really identified, the pandemic supposedly left the world with a shorter supply of food, materials, and the labor to produce them. But there’s just no evidence of a permanent change in supply and demand, outside of the bullwhip effect caused by global shutdowns and re-openings. Indeed, the same domino effect which saw everything rise in price on the back of crimped supply is now seeing the same effect in the opposite directions. Everything from grain to lumber, from used cars to copper has started the journey back to pre-pandemic prices.

Deglobalization is also seen as a pandemic recipient. And here, deglobalization does triple duty: not only as a theory about itself, but as an accelerant to regime change in inflation, and scarcity. And yet, the political pressures on global trade have been mounting for forty years. In particular, the critique of neo-liberalism and free trade advanced with intensity the past decade, and played a key role in both the 2016 US election and the Brexit vote in the same year. Somewhat paradoxically, it was not protectionists in the west that put this trend into bigger play, notwithstanding the Trump administration’s half-hearted tariff regime. Rather, it was Xi and China policy that began to dial back domestic economic progress, getting bogged down in Hong Kong, human rights violations, and sabre-rattling over Taiwan. Indeed, the global race to build semiconductor capacity and battery production capacity outside of China, and very much in the west, is not the result of the pandemic or its effects, but a legitimate response to a very regressive turn in China’s political-economy.

What did the pandemic change? Surely it must have changed something. Work-from-home is very obviously the result of the pandemic, and works as a clean and crisp example of a new era outcome. The Gregor Letter has suggested previously that a break in the commuting mandate was probably inevitable, and the pandemic was unquestionably the catalyst. Anecdotally, you know, and we likely all know professionals who could easily be back in the office full time now, for five days and forty hours. Guess what? Employers discovered they could shed real estate leases and other fixed costs during the pandemic, and so it’s not just workers who like being at home, employers like it too. Indeed, the pandemic’s impact on how we work and commute will probably come to be seen as profound. The pandemic unlocked possibilities, and there’s no way to put all those realizations back in the bottle.

Finally, there’s the claim that a post-pandemic world is one where fossil fuels, even at lower growth rates, are in short supply. This notion is among the easiest to dismantle. Here goes: a crisis-led demand collapse leads to a supply fall, and then an economic rebound intersects with a war on the European continent, in which the aggressor accounts for at least 10% of world oil supply, and whose supply lines feed European natural gas dependency. That put coal in play, spiked oil prices, and started a kind of mind virus about fossil fuel scarcity. Dependency, not scarcity, should have been the lesson.

But price knocks down a weak thesis, and is doing so currently.

Concerns are mounting that as China re-opens a sudden increase in economic activity will spike the price of oil. But these concerns are largely overblown. The IEA estimates China’s oil demand over the 2021, 2022, and 2023 periods to run as follows: 15.4, 15.0, and 15.8 million barrels per day. To be sure, the rebound from this year’s estimate at 15.0 mbpd to next year’s 15.8 mbpd will place pressure on oil prices. It’s just not clear at all that this advance is probable. Political leadership, Xi mainly, has done alot of damage to China’s economic prospects, with mismanagement touching everything from the property sector to the internet sector, not to mention a weird if not bizarre approach to the pandemic. Under Xi, China has capped its own progress, digressing into self-destructive territorial obsessions over Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other points of micro-contention in the South Pacific.

In the background of these questions, China road-fuel demand has grown ever more slowly in recent years as EV storm the market, and auto sales more generally slow down from the torrid pace seen last decade. Moreover, OECD oil demand is either in a new decline, or, a permanent step-down from the flatline of the past decade. So, advances in China oil demand even if they materialize are not likely to have the kind of impact once felt so immediately in the global oil market. Here is a potentially useful rule of thumb now to gauge changes in China’s oil demand going forward: is leadership embarking on a new growth path? Or, is leadership swirling around the drain of its own haphazard geo-political focus? Until Xi makes a new move,

a quieter, more stagnant China is the base case. | A note on the data: IEA estimates of China road fuel demand in recent years have been wildly unstable, with revisions often taking back as much as 100% of previous reporting. The 2021 estimate you see here is probably valid, and reflects the rebound from the pandemic low. The 2022 estimate however should be treated with great caution, given the tendency towards revisions lower.

The transition of the United States from a heavy importer of energy to a net exporter is now a long term trend that clearly has room to run. It’s also important to understand how often this story gets mangled, jumbled up into deep error, by media actors that run the gamut from the ignorant, to the malevolent. As always, it doesn’t have to be this way. Let’s begin here:

The US produces energy of all types. Everything from oil, coal and natural gas to electrical power driven by nuclear, hydro, wind, and solar. And then the US consumes energy of every type in transportation, heating, industry, and in homes. In recent years, however, the amount of energy that the US exports has actually started to blot out the energy it still imports. Enough so, that the US has finally moved out of its post-war energy deficit, into a small surplus. In other words, from a trade balance perspective, its current account in energy terms is now positive.

Let’s take the year 2021, as an example. In that year, the US consumed 97.844 quadrillion btu (“quads”) of energy from all sources. But in the same year, the US produced 98.306 quads of its own energy, again, from all sources. That looks good, because it equates to a surplus of 0.462 quads.

Of course, the US doesn’t produce enough of every single energy source to feed itself entirely from its own supply. Well wait, actually, the US almost does accomplish that feat, with the exception of one source: oil. That’s right. The US produces all the coal, natural gas, wind, solar, nuclear, hydro, and biomass that it needs, and it exports surpluses of two of those: natural gas in the form of LNG, and coal. But it does not produce quite enough oil, and needs to import some.

But the US turns around some of that imported oil however, after transforming it into much more powerful petroleum products. According to the EIA, the US enjoyed a net energy export surplus of 3.616 quads in 2021. The reason that figure is higher than the simple difference between production and consumption, of 0.462 quads, is that some of the energy we export is very high in energy content: coal not so much, but LNG yes, and especially petroleum products, like gasoline, jet fuel, diesel, and other petro products.

Readers are probably used to examining the US trade deficit, which of course is expressed in dollar terms. Here, we examine this trade balance not in dollar terms, but in energy content terms—quads. And as you can see, after running in the red for a long time (certainly longer than is covered in the chart) the US has now moved into the black. Net imports, which used to be positive, are now negative. That’s a powerful position to be in, and we saw an example of this power just this year, when American LNG started making its way to Europe, during Putin’s war of aggression.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to Dropbox Shop. All paid subscribers to The Gregor Letter are granted access to Oil Fall for free.