Slowdown

Monday 21 March 2022

This year’s global oil outlook is already deteriorating, as the IEA cuts demand estimates by one million barrels a day. While producers will certainly pump what they can to capture high prices in the near term, they are even more unlikely now to invest heavily in new supply as the prospect for future demand growth dims further. This is the emerging conundrum that may dominate the oil and gas market for at least several more years. A world without demand growth is a world in which the trailing 5-7 years of oil-capacity underinvestment doesn’t turn around, doesn’t get better, but actually gets worse.

Demand destruction is a very hard phenomenon to predict. But we must try. New readers to The Gregor Letter are always encouraged to review recent issues in the archive, but especially letters War Zones I and War Zones II which lay out a case for roughly 3 mbpd of global demand destruction this year. Should high and volatile oil prices dominate for the rest of 2022, this change in demand would erase the entire forecasted increase originally laid out for 2022, by the main agencies IEA and EIA. Of course, uncertainty over oil price direction couldn’t be more intense. There are plausible scenarios in which oil prices stay elevated around current levels, or spike again to even higher levels around $200, or, collapse in spectacular fashion as the global economy sinks into a more pronounced crisis. Could oil prices in futures markets go negative again? Indeed they could: especially after a sustained period at nosebleed levels around $200. All this said, the fact that IEA immediately cut 1 mbpd is a sign of the central tendency. Demand will absolutely take a hit this year.

Not everyone agrees of course. In a recent Odd Lots podcast, Pierre Andurand made the case that this time around demand destruction will not really kick in until much higher prices, around $200. His reasoning: the inflation adjusted price of oil means we need to get to much higher nominal prices to trigger the necessary changes in demand behavior. The Gregor Letter strongly disagrees with this argument. Humans respond to nominal prices, not real prices, in the near term. And humans also respond pretty regularly to rates of change, rather than actual levels. If you raised petrol prices by 50% over two years, consumer psychology would not be that troubled. But raise petrol prices by just half that amount in 4 weeks time, and consumers will recoil—and not just at the pump. In other words, Andurand’s argument may be sound if, say, a US household were to tally up income, outlays, and sectoral spending for the past twelve months to conclude, oh hey, those high nominal prices really aren’t so bad on a real basis! But this is not how human psychology works. In the US, petrol prices were already front page news before the war. And now petrol prices are a major political lever, actually causing governors of blue states to suspend petrol taxes. Again, the argument about real prices is not just entirely countered, but overwhelmed by the evidence coming from the political realm. Readers once again will detect a recurring theme sounded out for 2022: fossil fuel prices will confound policy around energy transition.

In the IEA’s most recent Oil Market Report, released Tuesday 16 March, the agency embarked on what The Gregor Letter predicts will turn out to be not just one cut, but an extended demand cutting campaign. Notably, the IEA front-loads its 2022 downward demand revisions to Q1 and Q2, with a rebound in demand in the second half, to project an annual average demand cut of just 1 mbpd for the entire year. But there is no reason to believe that demand gets better in the second half. Indeed, the history of demand destruction shows that once the behavioral trend gets underway, it is hard to stop. Indeed, demand destruction this time around has all sorts of new themes that potentially take outcomes far beyond orthodox demand pressures that occur as a result of booming growth—as was the case in the 2005-2008 period. As the last two letters pointed out: the current energy shock is not just at the pump: it’s becoming embedded in a far broader awareness around fossil fuels, war, security, and vulnerability.

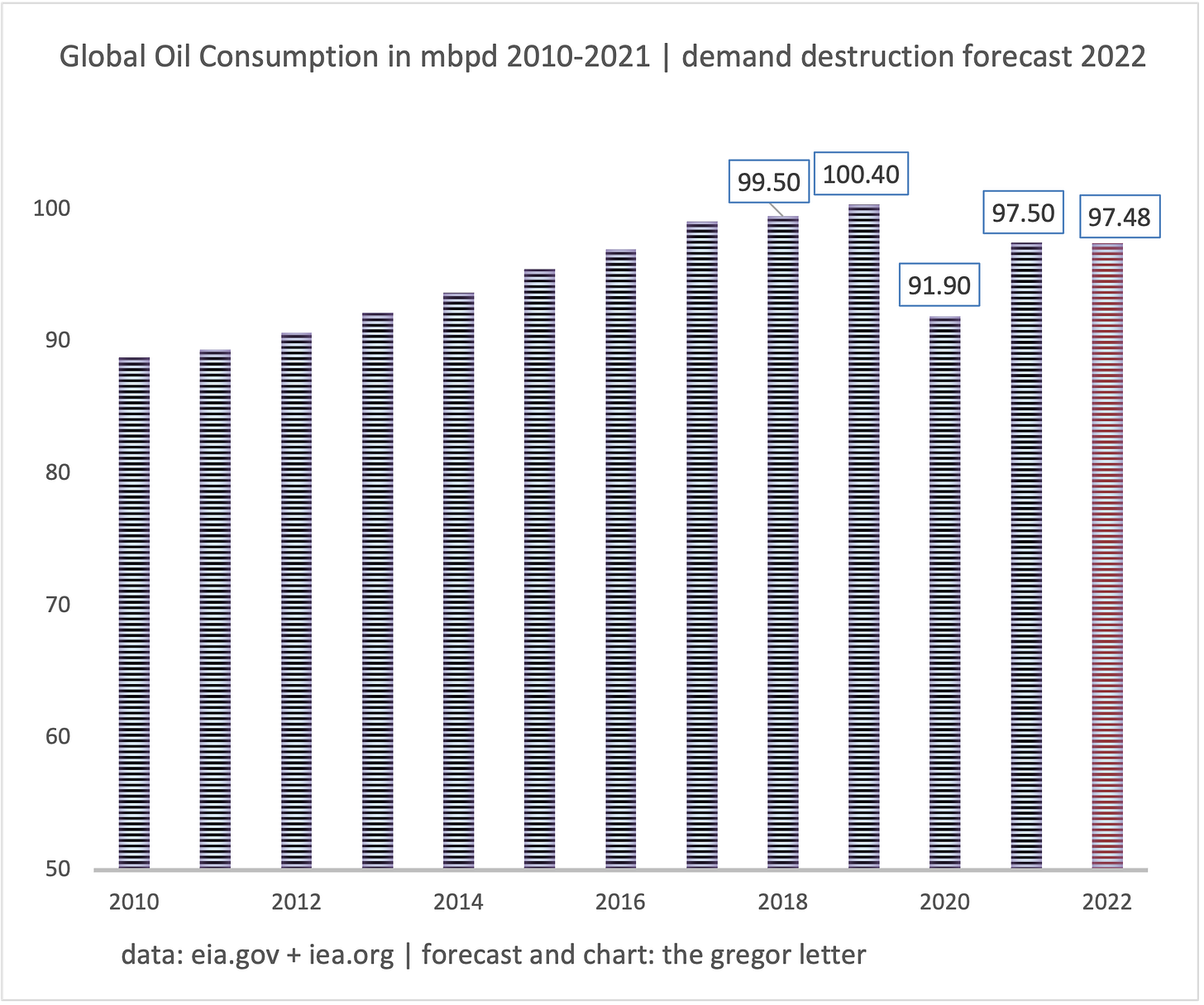

In the chart below the latest outlook from IEA (Paris) is blended with pre-2018 historical data from EIA (Washington). This is slightly unconventional, but during this period of high volatility—economic, geopolitical, and sectoral—this is the best way to provide a legible update. Note: the EIA generally follows the IEA on global oil forecasts and historical data. And while the two agencies are out of sync with each other in this regard on a short, four to six week basis, over time the two data series converge. Accordingly, the data attributions in the charts are for both agencies.

And here is the current forecast from The Gregor Letter, showing a more severe demand decline to 97.48 mbpd. Because 2021 was slightly revised upward, this demand destruction forecast now suggests there will be zero oil demand growth this year.

The case for a peak in global oil consumption and the beginning of a plateau is stronger than ever. As readers can see, regardless of whether one prefers the current IEA downgrade or The Gregor Letter downgrade of 2022 oil demand, the case for a 2019 peak is gathering strength. And that matters, because the portrait of a world that no longer has oil demand growth will immediately feed into the decision making of oil producers, with inevitable results. Just to remind: the notion that global oil demand was near a peak is an idea that’s at least five years old. It was a central case in the 2018 Oil Fall series. But the pandemic, and now the Russia-Ukraine war, have likely brought that peak forward—from a previously anticipated timeframe right around now in 2022—to an earlier date, around 2018 and 2019. Frankly, given what’s about to unfold in demand destruction and global EV adoption, the prospect that global oil demand will ever again put together back-to-back years at higher levels is remote.

Now that electricity is a transportation fuel, all that remains is to move demand over to the powergrid. Combined wind and solar are now approaching, or even surpassing, a 25% share of powergrid generation in California, Texas, the UK and Europe. Importantly, growth of new wind and solar in the three major world domains of the EU, US, and China is far outdistancing new demand from electrified transport. This fact still runs up against intuitions however, that somehow we won’t have enough new electricity to run electrified transport. That enduring misunderstanding has a simple explanation: it just seems impossible to most people that the amount of energy required to run an electric vehicle is at least 50% less, if not 60% less (or more) than running a vehicle on petrol. That differential is just too substantial for most people to incorporate into their thinking.

For example, here in the United States where EV adoption is finally getting started, the amount of new electricity being generated each year from new wind and new solar far outdistances new demand from on-road EV. A very healthy ratio of new clean power to new on-road EV demand might be somewhere in the 5X to 10X range. So how does 30X to 40X grab you?

The deployment of new wind and solar in the US has come in waves over the past decade, and a new wave is underway. Wave one began roughly twelve years ago, as the first mega-scale solar arrays came together in their planning stages, and as wind power stormed the Great Plains. That wave pushed hard into mid-decade, and gave way to a lull. You can actually see some of that in the previous chart. Then a new wave began during the pandemic year and is now about to rocket even higher. Here’s a look at the big picture so far: the progress of combined wind+solar as a share of total US power generation. Note the doublings.

Combined wind and solar will easily reach 20% of US power generation by the year 2025. That is extraordinary. And how will this be done? Through a new round of wind and solar at the utility scale in states like Texas, at the small scale through further rooftop deployment, and then later through new offshore wind power. Indeed, from this point forward, the amount of net new natural gas capacity is going to make very little progress, and wind, solar, and storage are going to entirely dominate growth. Take a look, for example, of how new generation capacity is already shaping up for this year, according to the EIA:

To gather support domestically for energy transition the US needs to undertake a far better political strategy. If it fails to make this change, and make it quickly, then political polarization will capture the effort, carving and slicing up long term goals into ineffectual pieces. That’s why the announcement this week of a plan to locate battery manufacturing capacity in West Virginia is encouraging. Plainly put, the US needs to site industrial capacity for the production of new energy in those US states where the economy is weak. It’s frankly a wonder this idea floats around from time to time, with little if any action. A simple approach would be as follows: blend the list of highest-poverty states in the US, with a list of states that have long depended either on coal extraction or coal combustion. Really, it’s not that complicated.

The global economy is going to slow down appreciably, largely tracking the hit to global oil demand. With uncertainty so elevated, however, it’s impossible to forecast how the rest of the year will proceed. A more benign slowdown might actually give supply chains further time to heal; and a relaxation of demand more generally may help ease inflationary pressures. A more acute slowdown would on the other hand unquestionably lead to a global recession. And it’s not just the energy shock and the instability caused by the war that threatens such an outcome. A looming food crisis, one that plays out over a longer cycle, is also forming on the back of crimped supplies of grains from Ukraine. The UN’s World Food Programme is warning about the supply chain, and the IMF is looking at both energy and food disruptions to also warn about a slowdown. It’s a certainty that the IMF will soon downgrade global growth.

The nickel market trading fiasco at the London Metals Exchange is a reminder that during periods of high volatility it’s not just prices but whole systems that break. Russian sanctions have understandably triggered wild trading in energy markets, but also in the nickel market—a reflection of Russia’s role as the world’s top producer, via its company Norilsk Nickel. This is yet another challenge to energy transition owing to the crucial role nickel plays in new energy technology—batteries in particular. Readers may recall the fuller discussion of the crucial metals required for energy transition in the 21 November issue Worlds Collide, and the cited paper, Metals May Become the New Oil in Net-Zero Emissions Scenario.

Military analysts are converging on a near-term conclusion: that the first thrust into Ukraine by Russian forces has now culminated. This is not necessarily good news however. The term culminate is meant to define the moment that a military force cannot continue, on its present track. For a fuller explanation, see the report of 19 March, 2022 from the Washington based Institute for the Study of War. This likely means that until Russia gets a new war plan it may be restricted to aerial bombardment, which is already terrible, and could become far more horrific.

A moral problem that may begin to arise for the West is that Russia’s invasion increasingly looks less like a war, in which military targets are the prime focus, and more like mass scale murder, with predominant targeting of civilian infrastructure, and civilians themselves. To be sure, the totality of Western sanctions against Russia, along with the surreptitious military aid to Ukraine, has been far more devastating to Russia than many critics are inclined to admit. We must also remember that Western intelligence agencies are no doubt providing Ukraine forces with actionable information. This is all good.

But these actions all seem to imply that this is a war, rather than a depopulation campaign. One needs to be careful about applying the word genocide, but if Russia’s actions now swing even more concertedly to constant missile attacks on cities, attendant firing squads of civilians, seige tactics that starve trapped people, and the deportation of Ukraine citizens to Russia, then the situation may ratchet upwards to a more serious moral and existential challenge to the West. Should the invasion develop further along such a path, then it will become increasingly intolerable to have a 20th century horror play out again on the European continent. To be honest, it feels as if this moment is approaching quickly. And if that assessment is true, we should all be prepared for a more serious phase of the war.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.