Smoked

Monday 12 June 2023

While an outright decline in global oil consumption is still several years away, the building blocks to decline are showing up now in multiple domains. The current view of The Gregor Letter is that global oil demand peaked in 2019, and began a multi-year standoff that will oscillate in a range of 1.00% - 1.50% around the 100 million barrel a day (mbpd) level. This oscillation should break down sometime after 2025. A safe bet right now, for example, is that global oil consumption finally starts to decline in 2027. Here’s what that might look like:

While it sounds unnecessary to say because it’s so obvious, oil demand has three possible regimes: an era of growth, an era of stasis, and an era of decline. That middle era receives far too little attention. The US, for example, has been on an oscillating plateau in total crude oil consumption for fifteen years. And its gasoline demand has been on a plateau nearly as long. Please remember these examples each time your intuition tells you that peaks are followed by declines. They are not.

Each type of demand era is hard to achieve. It’s not easy in a growth era, for example, to retain all the demand from a previous year, while adding new marginal demand in the current year, only to then repeat the process the following year, for many years to come. Today, the world has now achieved stasis in oil demand, and that was no easy task. First, global auto sales of ICE engines had to peak. That happened in 2017, and China ICE sales peaked the same year. Efficiency gains in newer ICE vehicles had to keep pressing forward, and transportation solutions in public transit also had to make gains either through newbuild or resurrection of older lines. All that happened. Then EV adoption had to get going not just in cars and trucks, but in two and three-wheelers, which are so dominant in Asia. Historically, for example, India’s two and three wheeler fleet (the largest in the world) has collectively consumed at least as much if not more petrol than the country’s vehicle fleet. Finally, some behavioral change was needed and the world was introduced to work-from-home as the result of the pandemic. All these factors combined to get us to a plateau.

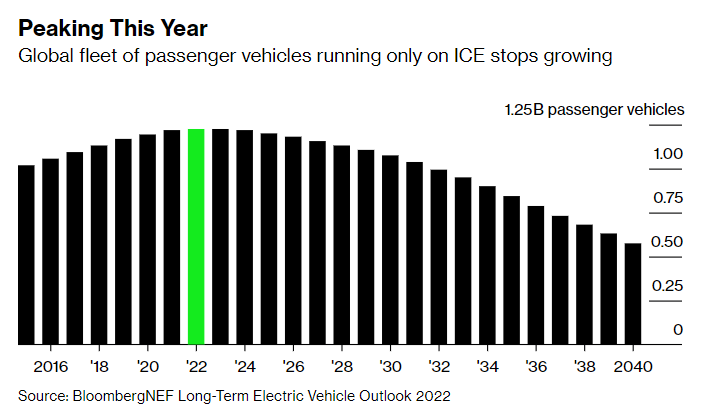

So why is global oil demand not declining yet? First reason: because the existing ICE fleet hasn’t peaked. Or, if it is peaking, that’s only occurring just now. Bloomberg estimated that the existing fleet of ICE passenger vehicles peaked last year. Even if true, however, the rollover is exceedingly gentle. Some are confused as to how global ICE sales can peak in 2017, while the fleet keeps growing, pushing a peak in the total fleet out later in time. The answer is pretty easy: ICE sales press onward at high levels (below peak) while at the same time ICE vehicle lifespans continue to lengthen, now at a record over 12 years.

This is the main reason why The Gregor Letter is looking after 2025, into 2026 and 2027 for a decline to begin, because these years approach the ten year mark after peak ICE sales, and, cars purchased in that year will start to retire. In other words, the first upsweep of EV adoption is additive, not revolutionary, in that it creates a fresh layer of zero emissions vehicles on top of the existing ICE fleet. The great replacement occurs when the ICE fleet peaks, with no help from ICE sales to match that decline. Again, the automobile era is over 100 years old; getting to the moment of decline is a process.

So, how do we get to decline? Well, California is instructive, and may even offer a template. The Gregor Letter suggested in December of last year that California petrol consumption, after plateauing for over a decade, was finally ready to fall. Let’s tally up the factors that finally caused the tipping point in California.

• 2015: ICE vehicle sales peak at 2.1526 million.

• 2017: State kicks off new, multi-step increase in petrol taxes and fees for ICE vehicles. These petrol taxes are still ratcheting higher.

• 2017: Annual petrol consumption hits a post great recession recovery peak of 15.58 billion gallons, a level not seen since 2005.

• 2018: EV sales break out above the 5% market share for the first time, reaching 7.27%.

• 2019: Total registered passenger vehicles (of all types, including EV) peaks at 26.3027 million.

• 2019: Total California population peaks after traveling along just below 40 million for several years, and begins a tiny decline of 7,000 to 10,000 people per year.

• 2020: Petrol consumption crashes but it’s not statistically valid, as it represents an outlier year caused by the pandemic.

• 2020: Work-from-home begins, and California’s tech and entertainment industries are perfect fits for the new lifestyle.

• 2021: EV sales break out above the 10% market share for first time, reaching 12.27%.

• 2021: ICE fleet peaks after several years of no growth, and starts to gently fall into 2022.

• 2022: EV sales soar to European levels, reaching market share of 18.73%.

• 2022: Annual petrol consumption makes a slightly lower low than the prior year, 2021, indicating a break with gasoline trends in the rest of the US.

The most important dynamic in the California story is that ICE sales peaked earlier than the US, earlier than China, and earlier than the world, in 2015. This means that by 2021, the average ICE car sold in California had reached middle age: 6 years logged, with 6 years to go. We might identify this as a shadow tipping point, as it sits halfway to the new average ICE lifespan of 12.2 years. Also by 2021, we had work-from-home, which in part led to some net migration out of the state as workers fled to mountain towns and other cities across the West. While we only have two months of gasoline data in the books for 2023, it seems highly unlikely that consumption will exceed 2022.

One way to think about EV in the early phase of adoption is that 1. they kill future growth of petrol consumption. 2. you actually have to get yourself into the future to see that effect finally unfold. :-)

Getting global oil demand to enter decline means we have to tick a number of boxes that remain empty, waiting for us to cross numerous thresholds. It’s great that ICE sales globally peaked in 2017 (as they did in China) which means we are just now coming into that shadow tipping point, as all ICE vehicles sold in 2017 reach their half-life this year. What the rest of the world doesn’t have under its belt, however, is a slight population decline, or a broad embrace of work-from-home, or a new regime of petrol taxes and fees for ICE vehicles. Moreover, the rest of the world (and the US too outside of California) remains very invested in petrochemicals and other industrial applications for oil. These factors play almost no role in California, which is very much a white-collar, digital economy.

It must also be said that the rest of the OECD, Europe mainly, has enjoyed falling oil consumption for years but this is because petrol taxes and mileage-efficiency have been way, way ahead of the US for several decades. Your correspondent lived and traveled in both the UK and New Zealand more than 20 years ago, and petrol was already $4.00 per gallon. Indeed, on an inflation-adjusted basis, US gasoline is dirt cheap today, somewhere below that same level.

The US could in fact kick off the global oil decline almost immediately, were it to align petrol tax policies, driving and road charges, and other transit-friendly policies as seen in the rest of the world. We know however this is not going to happen, for political reasons.

The IEA has forecasted that global oil demand will reach a slightly new, all time high this year around 102 mbpd. But the OPEC cuts confirm this is not going to happen, and once again the IEA tendency to overestimate demand will have to be revised downward. It certainly seems likely however that 2023 will see demand recover to the 2019 high, maybe a little higher, around 101 mbpd. Our model however allows for a 1.00% - 1.50% oscillation around the 2019 level as our baseline. In short, absent some newly dramatic set of policies that attack demand, which at this point could really only come from the US, we will have to wait for the ICE fleet peak, and the retirement of the 2017 ICE cohort, to work their magic.

In the meantime, we can say with confidence that oil and gas is a no-growth business.

All or nothing work-from-home forecasts continue to fail, as companies step up their recall of workers in the US. Banks, tech companies, and other US employers are increasingly asking workers to return to the office. This is expected. And as long as you avoided the extremes in your forecast, all is well. The Gregor Letter continues to believe that WFH will permanently impact at least 10-15% of workers in the OECD. This adds a bit of extra downward pressure on oil demand, but it’s important to remember that OECD oil demand has been falling in gentle phases for a long while, since 2005/2006. Morning Consult has the latest readings: Americans working from home dropped about 4% in the past year.

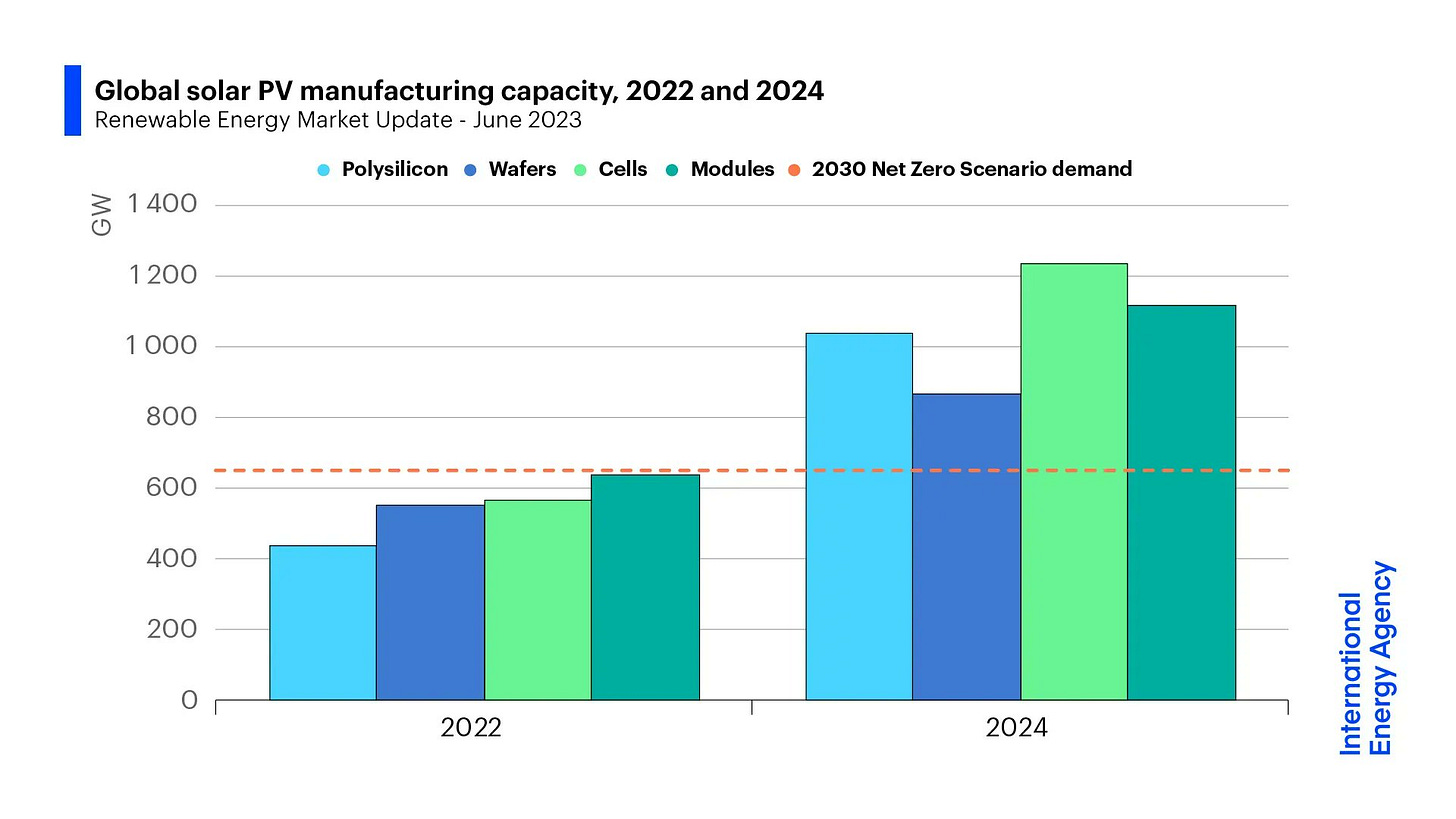

One of the inevitable outcomes in the growth of solar production capacity is the growth of solar generation capacity. According to the IEA, which just released its Renewable Energy Market Update 2023, output capacity in polysilicon, cells, and modules will all increase to over 1000 GW by next year, with wafers not far behind, just below 900 GW. It’s no wonder that forecasts of installations therefore keep ratcheting higher.

This also may explain why forecasts of global capacity growth in output are currently volatile, and frankly, upwardly volatile. Jenny Chase of Bloomberg is currently forecasting that the world will roughly install 340 GW of new solar this year, 2023. But, she adds, industry consensus is higher. Meanwhile, IEA, which is terrible at forecasting, projected in the above cited report that global generation capacity additions would reach 310 GW in 2024, compared to 286 GW this year. Unsurprisingly, the IEA is alone with such a low forecast for 2023, and as a result, their “growth” forecast for 2024 would, if it came true, actually result in a decline against the Bloomberg and industry consensus for this year.

The Gregor Letter thinks the following projection is far more likely. Output capacity is growing strongly, so 2023 is going to be a stellar year. But the spread between Bloomberg’s forecast and the industry this year could be resolved by pushing some installations into next year.

Urban smoke from wildfires has typically impacted West Coast cities, but this month the entire northeast was affected by fires in Canada. Air quality indexes spiked to dangerously high levels, people stayed indoors, and a pervasive sense of gloom descended upon the region. Fire, flood, drought, and heat were events or conditions that initially arrived individually to cities and regions as the effects of climate change increased in frequency. Now we are seeing clusters of these conditions, in the same locales.

With respect to New York city specifically, the past two decades have seen a number of notable shifts in the city’s climate. Several damaging floods associated with either hurricanes or tropical storms shut down subways and other public transit. These events have also been associated with partial blackouts. Also, the climate classification of New York City has changed from Humid Continental to Humid Subtropical. The big shift has occurred in winters, which are measurably warmer. Now, the city along with Boston, Philadelphia, is within range of large volumes of smoke from fires, and this probably indicates northeastern Canada is more vulnerable to the burn. The northeast has also had a couple of mild droughts. Nothing like the mega-drought affecting the West, but one has to wonder that too is now a risk.

The Federal Reserve is expected to pause its interest rate hike campaign when the FOMC meets this coming Wednesday, 14 June. The more pressing question however is: what would cause the Fed to start hiking again in July, if the same data trends that have justified a pause simply keep going? Inflation readings have come down steadily over the past ten months. Wage growth, which was also a concern, has also calmed down. Producer prices have also fallen; inventories of goods have risen; rents and housing prices have eased; and global inflation has also started to come down.

Global stock prices reflect the current outlook: a steady global economy with inflation falling means the value of earnings can rise once again. One important point: the relationship between tight labor markets and inflation is, again, not what a previous generation of economists had come to believe. Inflation is falling, despite the job market remaining strong. One possibility: modern economies may work better at full employment rather than lower employment because our supply chains and productive capacity are actually quite good, and throw off savings and efficiency when running hard. For example: what causes egg prices to rise, outside of a new demand source or an illness that kills chickens? Easy answer: spanners in the works of distribution. If all workers needed to run a national egg production and delivery network are on hand, you will get embedded into the price of each egg the efficiencies, also known as savings, that are intrinsic to the system.

The Gregor Letter doubts very much that any data is going to change enough after this week to induce the Fed to start hiking again in July. Yes, there have been historical periods where a start-stop-start dynamic took hold. But the wild aggressiveness of the Fed’s hiking campaign the past year was designed, in part, to prevent that outcome. So far, so good.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to the Gumroad storefront.