Snail Mail

Monday 10 August 2020

Risk is rising to the integrity of US elections in November as the United States Postal Service, increasingly the focal point of voter participation, comes under partisan and operational pressure. Starting earlier this summer, delays in postal delivery began to appear in many regions across the United States. Social security checks, postal delivery of medications, and ballot-by-mail delivery (in selected primary elections) have all been increasingly affected. At the same time, President Trump initiated a new propaganda war against voting-by mail, claiming it was a massive vehicle for voting corruption. These claims have received understandable pushback, even from a number of Republican senators. This eventually prompted Democratic leadership to write an open letter to the new Postmaster General, which served as public notice that assurances had been made to fix, or even reverse, any organizational changes that have slowed postal delivery times.

But no sooner had the open letter been published (and the meeting it refers to, between majority leaders Schumer, Pelosi and postmaster DeJoy) when the USPS announced on Friday night, August 8, 2020, that a new round of sweeping managerial changes would be undertaken. As a kicker, the USPS also announced that the special franking rates historically offered to state election operations for bulk ballot processing would more than double, from .20 cents per ballot to .55 cents per ballot.

Readers outside the US will likely be quite confused about how to interpret these events. Briefly: the USPS is a federal level agency, one of the few authorized in the US Constitution, that applies a single standard across the whole of the country. But individual states and election commissions have a wide range of rules and capabilities when it comes to voting by mail. In Oregon and Washington, for example, elections are exclusively conducted by mail, and the envelopes voters use to return ballots are pre-stamped. The intent in these two states is obvious: to encourage the greatest participation in elections. Other states have very little experience, by contrast, in voting by mail outside of allowing a very small percentage of voters to request the permission to vote in this manner. Many states put up difficult roadblocks to voting by mail, and do not offer pre-stamped envelopes. That may seem like a small matter, but anyone in marketing and sales knows that even small notches of friction can affect participation. And who has time to wait in line to buy physical postage stamps?

To make matters worse, we have seen this year that many election commissions across the country are so deeply incompetent that vote-by-mail ballot requests this year (on the rise obviously during the pandemic) were not answered in nearly enough time for them to be returned. Moreover, many states—even states that you might assume are friendly to mail balloting like New York—enforce highly punitive standards for returned ballots, and rejection rates can be high. Ballot design is done at the state level, for example, and is often poorly done if not awful. The Post Office meanwhile is supposed to apply a postmark to returned ballots that give proof to a common standard: that ballots be returned by mail no later than election day. But often that postmark is not applied. What we have therefore is a hodge-podge of widely varying state rules around mail voting, often with absurd outcomes.

Hanlon’s razor tells us to “never ascribe to malice that which can be explained by incompetence.” When it comes to conducting elections, designing ballots, creating mail ballot rules, and funneling these processes through the Post Office there is ample opportunity for ad-hoc, discretionary decision making at the state and local level to disrupt and confound the process of voting. But at least as often, elections in the US top-to-bottom are simply antiquated, and poorly executed. The USPS has also endured operational problems for years, after two decades of digitization that has driven a long term decline in postal volumes and revenues. And yet now, in 2020, the sudden market call on the mail-ordering of consumer goods has of course soared which, on one hand, is likely increasing revenues to the USPS but also straining the very same resources they’ve been trying to downsize in an era of falling postal service demand. When you read this story about slow mail delivery and voters not receiving their ballots for the upcoming primary in Minnesota, any complete and accurate explanation is quite challenging to formulate.

What’s needed, therefore, is a sensitivity analysis that projects how current polling spreads in swing states, in which Biden currently has a well established lead, could be affected when compared against an array of estimated, vote-by-mail failure rates. Wisconsin, long regarded as the tipping-point state in the coming election, is a good example in this regard. Barely won by Trump in 2016, Joe Biden is currently sitting on an average 6 point lead, according to RCP. Now apply a high rate of vote-by-mail participation in the state this November—but, with a general understanding that Democrats in most states have indicated they intend to use this method far more than Republicans. Then start applying various ballot rejection rates. It’s not hard to imagine how that 6 point lead could be chopped down to something more manageable. And, for those of you who remember Bush vs Gore in Florida in 2000, imagine not one but as many as 7-10 states engaged in very intense, post-election legal challenges as postmarks, late arriving ballots, and signature rejections are all piled up in both state supreme courts and the US Supreme Court.

And yet, there’s a twist.

To the extent Republican voters skew towards an older age demographic, and also towards rural areas, these nefarious but bumbling attempts by the Trump administration could backfire. Backfire on GOP turnout. This Autumn, most senior citizens will surely be looking to reduce their exposure to crowds, and historically seniors and rural populations in most states have relied on voting-by-mail, especially in regions where winter begins to strike as early as November. And those voters are very likely to be voting Republican.

So it’s probably not Biden’s commanding lead against Trump that could be ultimately dislocated by the pandemic, US Post Office problems, or the latest legal attacks and threats by Trump & Company. Rather, it’s the Senate races that could be affected, because the margins in many (not all) of those races are much smaller.

US light vehicle sales are on pace to decline by 16% this year. Globally, commercial and passenger vehicles are expected to fall by over 20%. The US figure comes via Calculated Risk. And, the global data via Huyndai research, as reported in the Korean press.

Electric vehicles were kind of a big deal in the early part of the 20th century. And shares of electric vehicle companies were hot, in the stock market. The research comes via financial historian Jamie Catherwood. In particular, Catherwood sees parallels between today’s flurry of special acquisition vehicles (SPACs) and similar market activity from 1890-1910 as investment professionals raced to bring public capital closer to start-up EV companies that had not yet listed on an exchange. | Note: Catherwood has also been interviewed on the Odd Lots podcast, in which he covers the 1918 Spanish Flu.

During the great recession, global oil demand fell for two years. After coming into a high in 2007, the crisis and slow recovery saw demand lower in 2008 by 1.1%, and then lower still in 2009, falling another 1.3%. The current pandemic is likely to produce a very different outcome, however. This year’s sudden stop blasted a far bigger hole in oil demand, creating a uniquely low baseline. It makes sense therefore to project some moderate quantity of growth for next year. As always, the question remains: how much?

The most recent update to the oil demand growth table (posted roughly once each month in the letter) shows that 2020 demand change estimates are being very slightly tweaked. Yet the song remains the same: global oil demand will fall between 8-10 million barrels per day (mbpd), a decline of 8-10%. However, the global agencies have now started to estimate changes to demand growth next year, and here the range is wider: OPEC sees over 7 mbpd of growth in 2021 while IEA Paris is closer to 5 mbpd. In truth, forecasting next year’s demand change is exceedingly difficult, as it rest in part on getting this year correct at a time when so much policy uncertainty exists in the world’s biggest consumer, the United States.

And that’s precisely why The Gregor Letter is at the bottom of the growth table, for 2021. The broad and ongoing failure to utilize available 21st century technology and practices in the US to manage the pandemic keeps pushing the US recovery out further in time. That fact alone impacts world trade, consumption, and—not just oil demand here—but everywhere.

Despite the policy uncertainty still to come, it is still advisable to assume oil demand growth will at least carry a +sign next year. Even The Gregor Letter forecast, which appears “low”, at just 3.25 mbpd of growth, represents a big bounce in percentage terms of 3.6%, as we come off the very low base of 2020. For the industry, the takeaway remains grim: a growth decline of 8-10% this year, followed by a recovery next year that claws back only a portion of the decline. Again, given all the changes currently underway in global transportation—many of which are converging towards the year 2025—this is why it’s now too late for the industry to ever regain its previous growth path. Oil is now a dead-money, no growth industry, fated to experience brief upticks in the context of long-term stagnation and eventual decline.

New Mexico is the latest state to approve a major coal retirement in conjunction with a plan to replace the capacity with solar, and storage. The supertrend continues. The San Juan Generating Station, with just under 1 GW of remaining capacity, will close in 2022. Roughly 1.1 GW of renewable generation will be deployed as part of the plan (led by solar) in conjunction with 300 MW of storage.

The global fleet of coal-fired power stations contracted in the first half of this year. That’s according to a new report from Global Energy Monitor, in a post published by CarbonBrief.

Just to remind, global coal consumption peaked in 2013 at 161.98 EJ, and then proceeded to oscillate on a plateau for 6 more years. But the outright decline is finally here. There’s another, more important point to make on the matter of coal, and its historical record over the past 250 years. Although superseded by oil starting in the latter half of the 20th century, coal of course enjoyed a re-boot starting in 1990 when Asia industrialized. Coal 2.0, as it might be called, was a retort to the common intuition that energy sources completely die out, and never enjoy a resurrection. This time around, however, the combination of wind, solar, and storage is so powerful that, unless humanity experiences some unusual bottleneck in technological development or material availability, we will never see Coal 3.0.

Hyperboloid cooling towers, developed by Frederik van Iterson in the early 20th century, are starting to disappear. A big piece on the trend in the Financial Times noted that 1/3 of the towers originally constructed in Britain have now been taken down. Because the towers are so deeply emblematic of the thermal power era, it’s worth speculating all the other associated infrastructure that is now fated for no-growth, or disassembly. The obvious: oil refining capacity, pipelines, port infrastructure for the export or import of coal, natural gas and coal fired power stations, and coal trains. If you haven’t already, do read John McFee’s massive, two part series on coal trains in The New Yorker—written last decade in the heart of Coal 2.0—as it remains classic of the genre.

The stock market continues to forecast an extremely robust recovery for 2021. Analyst consensus SP500 earnings for next year remain stubbornly high, projecting a 100% recovery that matches earnings from 2019. Accordingly, the forward P/E ratio is also quite high and far out of average range, as FactSet illustrates here.

While The Gregor Letter base case remains unchanged, the lights continue to dim on the pace of recovery. The current wave of the pandemic has of course caused the nascent rebound to stall. Now comes yet another absurd development, in which the President has attempted, through dubious executive orders, to craft a synthetic spending and relief bill outside the congressional process. If these actions endure, and are not supplanted immediately with a normal congressional bill that supplies maintenance money to workers and state governments, then evictions, permanent worker separations, and other networks will start to fail as consumer spending exits the flat-zone and begins a new decline. Already, the economic impact of the current wave has not only done damage, but will sustainably unleash more damage as Autumn sports are cancelled, universities only partially re-open, and workers in cities do not return. Rents are falling in leading US cities, and in university-driven regions like Boston the impacts on real estate could be significant.

While the stock market continues to probe further recovery highs however, both US treasury bonds and now gold continue to forecast deflation—and in the case of gold, an extended period in which central banks will have to fight deflation. Tellingly, just this past week, the yield on the US Ten Year Treasury bond probed the .50% level—not seen since the market panic in March, when global capital surged into US treasury bonds pushing their yields down to extremes. One takeaway from the current market action is that without panic, and without large declines in stocks, government yields revisiting the panic lows suggests that money demand is falling hard. Indeed, there is recent data showing that Americans continue to save dollars, pay down credit card debt, and are avoiding taking on new obligations. No surprise. Gold meanwhile is thriving on negative real rates, as the actual rate obtainable on a US treasury bond is now lower than inflation itself.

The risk is that the liquidation phase of the current crisis—effectively staved off with maintenance money—could still lie ahead because markets of course price at the margin. US domestic real estate, like US equities, continues to hold its value because homeowners have either had their mortgage payments suspended or have received enough government funding to hold the line. Indeed, it is impossible to understate how helpful it has been to stave off the liquidation phase, because that process triggers an array of damaging effects that very effectively propagate through the economy. So far, few if any are being forced to sell their cars, boats, houses, or stocks. And it shows. But should that phase get underway, it will be hard to reverse.

In the last letter, it was fully acknowledged the adult supervision and rational policymaking from a new administration next year could indeed trigger such a massive rebound in confidence, that the elusive V recovery which everyone seeks could very much unfold. But it’s important to remember how much further damage can be done between now and then. And also this: the current recovery is not a “V”, and is now clearly a square root shaped recovery, but could easily become a “W” if immediate aid is not forthcoming.

Markets offer imperfect signals and gold in particular is both tricky and unreliable in this regard. Sometimes gold is a risk-on asset; sometimes a risk-off asset, and contrary to popular intuitions, gold does better when central banks are fighting deflation than when they are fighting inflation. But there is no question that gold sees those falling interest rates, and, is luxuriating in that light. The more reliable signal is the direct one: falling interest rates, heading back to the panic lows of March, are sending out a warning. The warning is clear, and unambiguous.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

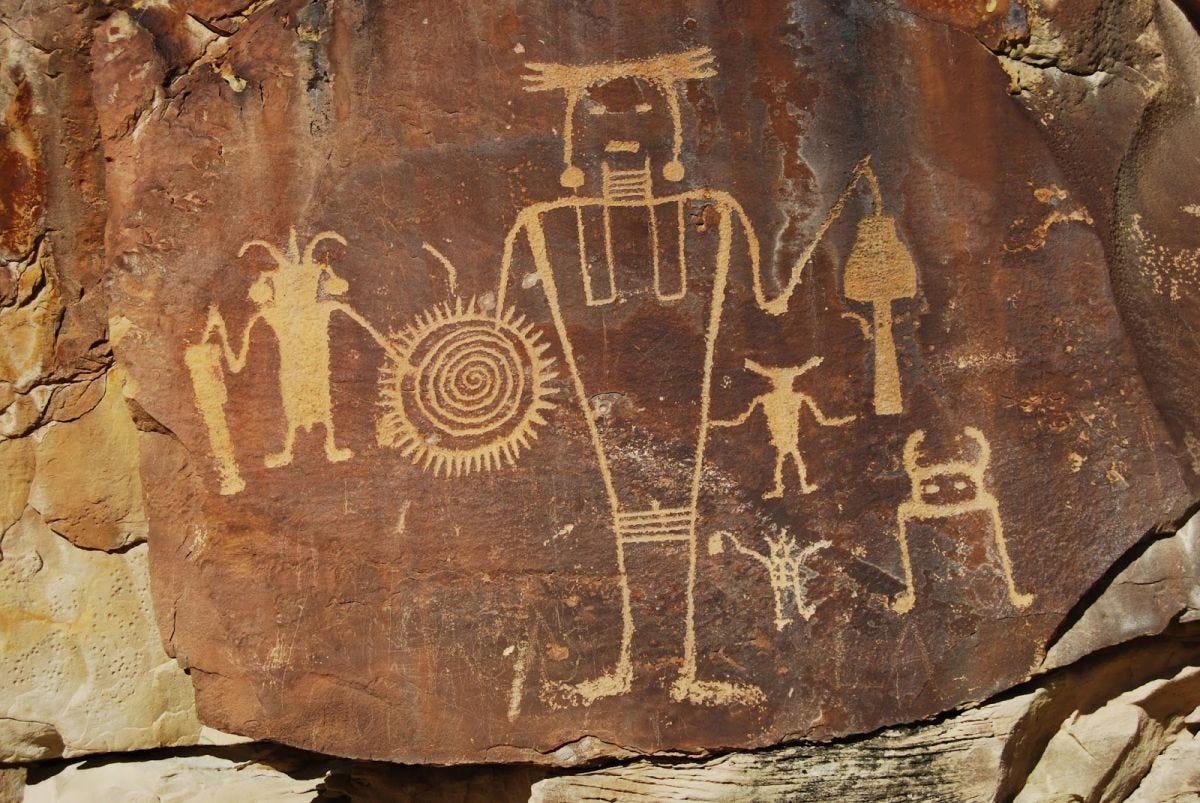

Photos: 1. US Post Box, Portland, Oregon 2018, Gregor Macdonald. 2. Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter, Portland, Oregon 2019, Gregor Macdonald. 3. Petroglyph National Monument, Albuquerque, New Mexico. 4. Cooling Towers, Herleen, the Netherlands, 1918.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.