Springtime Rollouts

Monday 1 May 2023

The return of Ford Motor Company to downtown Detroit signals a willingness to play in the new reality of mobility. Students of industrial history will know that the vehicle manufacturing sector has gone through various bundlings and unbundlings as the components needed to build vehicles migrated towards specialization. Indeed, the underlying force in the decline of the city of Detroit began early, when concentration in the auto sector began to disperse and manufacturing activity devolved to a regional map spread across not just Michigan but Ohio, Indiana, and Canada. Today, the global auto industry is splayed across a supply chain ganglion that’s global. Ford’s purchase and rehabilitation of Michigan Central Station and the adjacent Book Depository building originally designed by Albert Kahn, is therefore both a nod to the past but also the future. Not only will we transition to electric cars almost exclusively, but cars will likely have to share the road, and the transportation landscape more broadly, with an ecosystem of new mobility that includes bikes, e-bikes, and other multi-modal solutions.

Further reading: Ford to unveil newly rehabbed Book Depository in Detroit.

The legacy auto manufacturers continue to face a battery supply constraint, a result of having come late to the game. Thinking has certainly changed at Ford and other OEMs as the transportation landscape heads into a more volatile phase. But the long head start into the EV supply chain realized by Tesla, for example, continues to highlight the challenge the US legacy names face in ramping up EV production to higher levels. GM, for example, inexplicably just cancelled its popular Bolt—a small passenger car that had been growing strongly in the market, based in part on its affordability. GM’s May Barra appears to want to shift strategy towards larger EVs, trucks in particular. But perhaps it’s time to really question whether GM has a profound strategy problem. They cancelled another popular offering two years ago, a plug-in hybrid called the Volt, that offered fairly high mileage in electric-only mode. Now, after soaring Q1 sales of the Bolt, they’re cancelling that too?

Ford meanwhile is further down that track, with an electric F-150 truck already on the market. But note that orders for the Lighting (e-150) are stacked up as Ford doesn’t have the capacity to meet demand. The result: the Lighting has steadily risen in price, which could suppress future demand if it becomes widely perceived that the Lightning is both hard to source, and carries a premium. That is not the legacy of the F-150, as the everyman’s truck.

Ford has also announced exceedingly ambitious plans for near-future EV output that seem, frankly, unrealistic. The company maintains its guidance to be building 2 million EV per year by 2026. We shall see. At its new facility near Memphis, which they’re calling Blue Oval City, the company intends to build half a million EV trucks per year. Sure, you can build that capacity, but when will Ford actually produce 500,000 EV trucks per year? Usually these announcements somewhat cloud the difference between capacity and actual ouptut. The uncertainty of course comes from the availability of batteries. Ford is of course in that game too, announcing in 2021 its intent to increase domestic supply (also in Tennessee) in a region that’s quickly becoming a battery belt. Overall, it is probably best to treat EV output forecasts with caution, while paying closest attention to actual progress in battery supply.

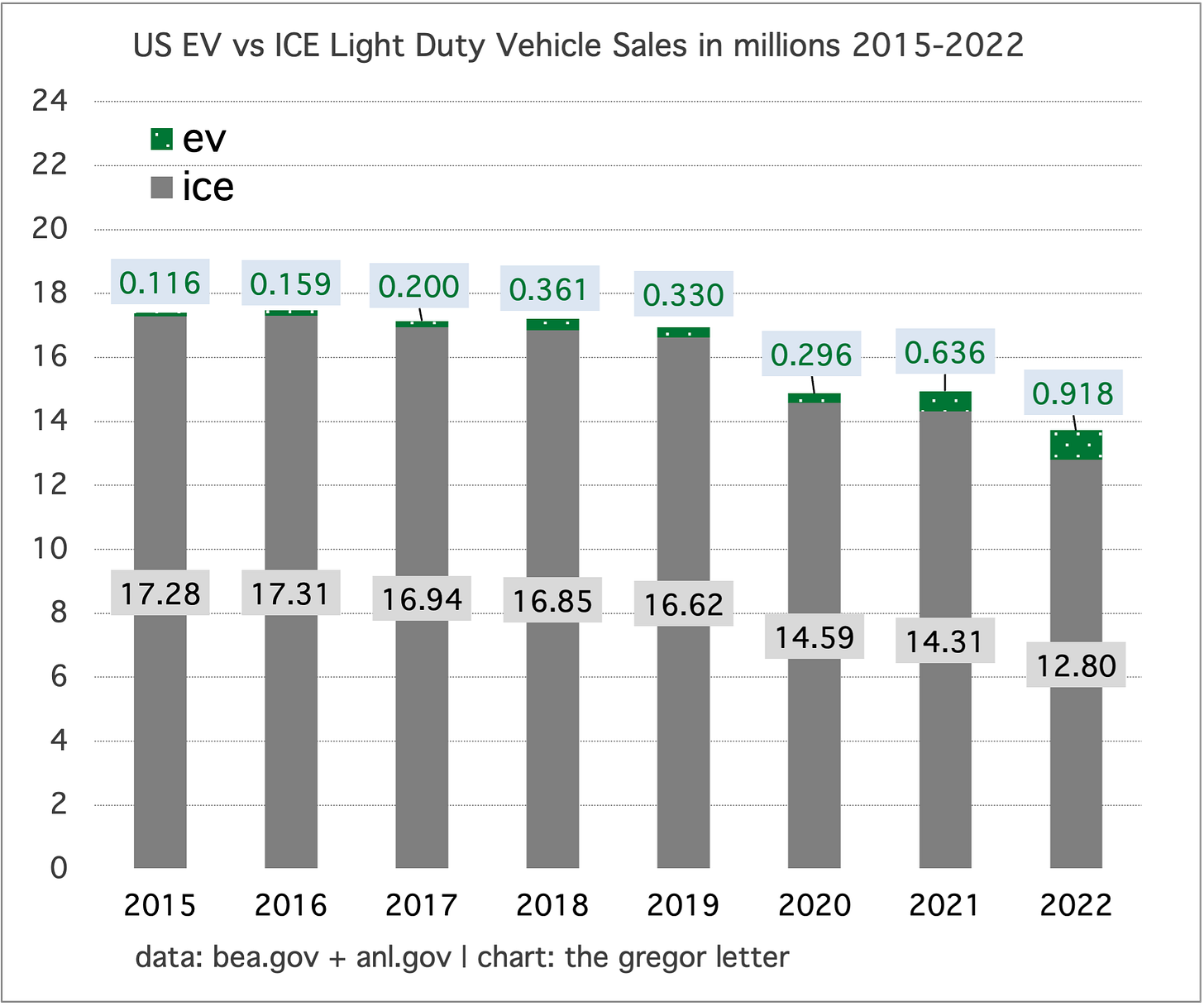

An ongoing transition in mobility and a higher interest rate environment have clearly suppressed the sales of ICE vehicles. One of the reasons EV are able to thrive in market share terms currently comes from the falling sales of ICE. Indeed, OEMs have to face two hurdles: they must re-tool to shift their product mix to EV, while at the same time consumers are likely to become wary of investing much further in the ICE platform. Share prices of the OEMs from Volkswagen to Ford and GM are not doing well currently, though one could plausibly claim that price action is in anticipation of recession risk. But when you see the chart below, no anticipation is required to be concerned.

As total vehicle sales fall, EV feast on the gap—rising in absolute terms. But the overall market is clearly smaller. Without question, the Osborne Effect is very much in play here. And vehicle manufacturers and the analysts who follow them may need to prepare for a surprising outcome: unlike in consumer electronics, where buyers hold off for up to a year or two at most (deferring purchases until the latest mobile device is available) in the auto sector buyers my hold off for years and years as a rolling Osborne Effect squats on the market until a fuller range of models and better pricing are available.

Electricity is the new “oil” that will fuel electrified transport, and in the US the distribution of power supply from clean sources is going well. There are now at least 15 states where combined wind and solar generation exceeds 20% of total in-state sales of electricity. In some states, like Iowa, South Dakota, and Kansas, there’s little doubt that some of their clean generation is exported. So, operationally speaking, Iowa (IA) did not supply 83% of its own power consumption last year exclusively through wind power. They likely exported nighttime surpluses to neighboring grids.

Regardless, the chart below shows that the mighty ascent of wind and solar power is becoming well distributed through the US. California and Texas are the big prizes, of course. Wind and solar taking 30%+ share in those states is far more consequential than Colorado’s 35%. But it bears repeating that the more wind and solar we create locally, the better. While HVDC technology is great, we can constrain costs in new clean power by making sure we avoid transmission over long distances.

Nota bene: in the chart below, blue bars are for states where wind is predominant, and gold bars are for solar states.

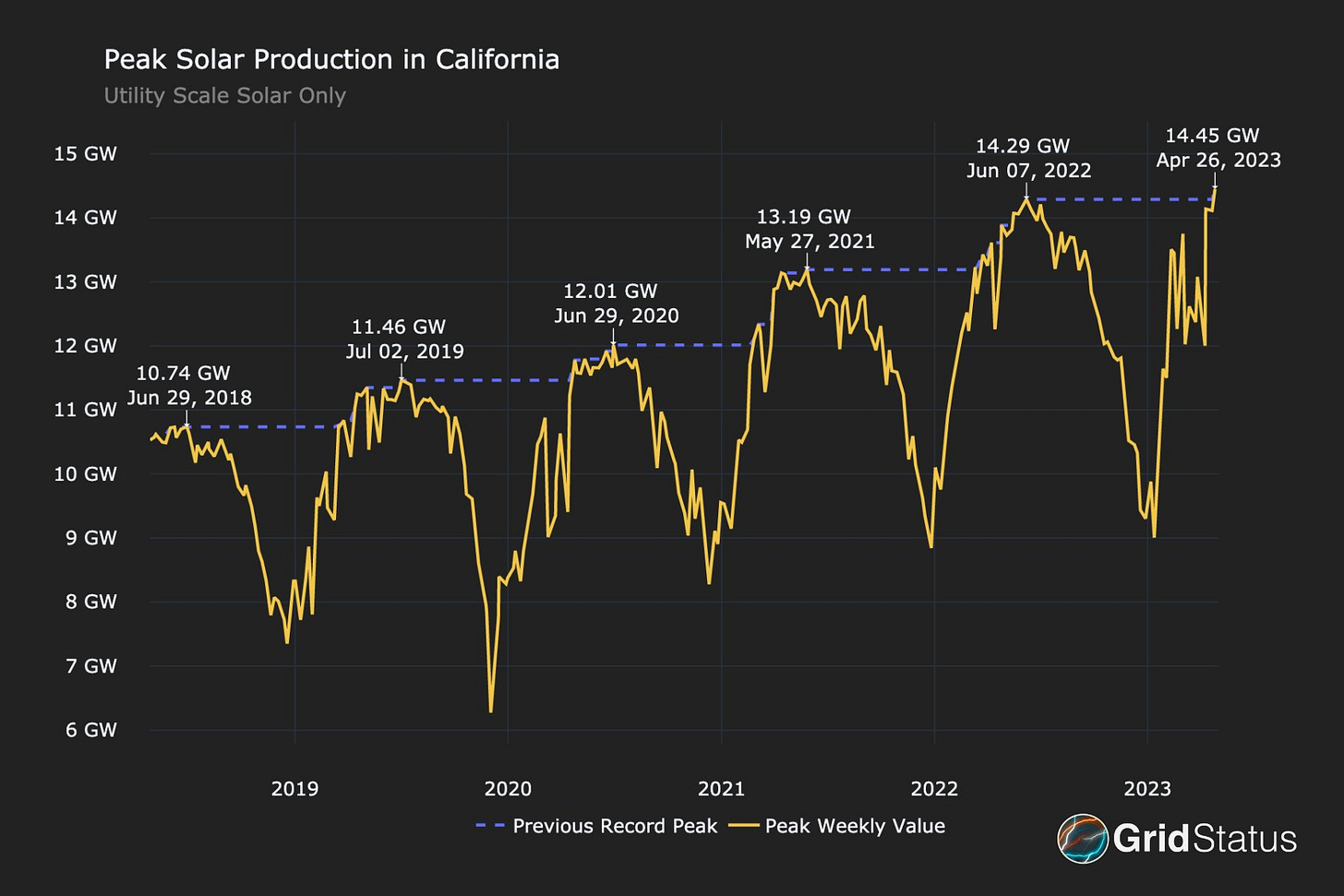

In related news, California solar production is hitting new all time highs this Spring, and that’s not even counting rooftop solar. Note on units: we typically measure electricity generation in hours, as in TWh or GWh over the course of one year. But there is another way to express generation, and that’s in simpler power output terms. The chart below uses that expression, GW or gigawatts, because what’s being captured here is peak output that itself is not restricted by time. Indeed, these peaks shown here are quite fleeting! That said, the power unit does tell us about the ongoing potential as solar power continues to thrive in the Golden State.

The economics of rooftop solar are never going to be as competitive as utility scale solar. But the impact on emissions and overall decarbonization from small scale is substantial. Put another way, do we really care how much every bit of clean energy costs, given the future losses we are due to suffer, from climate change? In a way, the argument for small scale solar is not dissimilar to the argument in favor of nuclear power. We already know that utility scale wind and solar will continue to be the primary forces in global decarbonization. Around the edges, therefore, we should add 1. some nuclear, and 2. as much rooftop solar as possible. Look at what small scale solar is already doing for the US: 58 TWh last year out of a total of 200+ TWh! Small scale solar also builds in a ton of resilience. And, as important, small scale generation is typically used on site, as it’s being created, with few line losses. More expensive? Who cares! If we expand small scale solar steadily, that means utility scale solar (and wind) can be increasingly devoted to power provisioning for much larger tasks, like making clean hydrogen at industrial scale.

Clean hydrogen production remains in its infancy, which means discourse of how best to proceed is contentious. A brief review: hydrogen has a transportation problem, a demand problem, and a price of production problem. Government incentives in the form of the Inflation Reduction Act will meaningfully lower the economic hurdles associated with making hydrogen from zero-carbon electricity. All good; that takes care of the price problem. But hydrogen production needs to be ideally located near a demand center, and that means as a product, hydrogen must be produced locally until transmission/transportation networks are established. Whereas wind and solar typically plug in to existing distribution networks, hydrogen has no platform ready and waiting to help out.

But there’s a broader, systemic challenge to making clean hydrogen. Unless we produce hydrogen entirely from clean sources (hydro, nuclear, wind, solar) then deployment of hydrogen production capacity via electrolysis will place new demand on any existing powergrid. And grids, while decarbonizing, are still largely composed of natural gas and coal-fired power. This is the point made by Leah Stokes, in a very good New York Times Op-Ed, Before We Invest Billions in This Clean Fuel, Let’s Make Sure It’s Actually Clean:

First, hydrogen projects must draw on new clean power. If a hydrogen plant just pulls clean power from the grid, then it’s not creating additional power; it’s simply diverting power that could otherwise be used for running an electric vehicle or heating a home. In fact, it would actually make the grid dirtier, since most utilities would respond to the increased demand by burning fossil fuels. That hydrogen cannot in any honest way be called “clean.”

This is hard. The US has a number of nascent, clean hydrogen projects starting to appear, one of which is located adjacent to a nuclear power plant in Oswego, New York. You can see the problem: as hydrogen production exerts a “pull” on power created by the reactor, this new demand coming onto the grid means additional power in the network must be created to meet existing demand. And in New York, that power is mostly like a mix of hydro, other nuclear, but especially natural gas.

This is one reason why some theorists believe early iterations of clean hydrogen production might be best paired with wind power. Those high penetration numbers shown previously, in states like Iowa, Kansas, and the Dakotas? Yes, something like that. Of course, one then still has to solve the demand problem: is there demand in the Great Plains for clean hydrogen? Not as much. This is why the emerging offshore wind farms coming soon to the US east coast are so promising: not only will they begin to suppress natural gas growth in the region, but, hydrogen production could take place at night, and serve a wider variety of industrial users between Virginia and Massachusetts.

The US offshore wind industry gets started for real this summer, as two wind farms will complete construction, and start producing clean electricity before the end of the year.

• South Fork Wind Farm, a 130 megawatt project will have 12 turbines located 35 miles east of Montauk Point and deliver power to Long Island. The project is developed by Orsted and Eversource.

• Vineyard Wind 1, an 800 megawatt project will have 62 turbines located 15 miles south of Martha's Vineyard and deliver power to Massachusetts. The project is developed by Vineyard Wind, a joint venture of Avangrid Renewables and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners.

There was a good write-up from NPR on the cable laying part of the project. And here is a good photo grabbed from the Cape Cod Times, showing how the cable comes ashore in Barnstable.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to Dropbox Shop.