Still Waiting

Monday 17 April 2023

The Biden Administration’s newly proposed rules to spur faster EV adoption confirms the US has no real plans to effectively cut emissions from the existing vehicle fleet. And without such plans, future emissions from the transportation sector will indeed fall, but they will fall much later in the 2020-2040 timeframe. The US could be working with individual states to introduce congestion charges and an array of incentives/disincentives around miles driven and ownership of internal combustion engine vehicles (ICE). Instead, the entire policymaking complex—top to bottom, from Washington to the local level—has concluded that measures taken against the existing fleet are politically untenable. A view, unfortunately, that’s not unjustified.

The discourse around the proposals has descended quickly into minutia, over-focusing on whether battery or other materials and manufacturing costs will fall quickly enough to meet the headline target: 66% of new passenger vehicles sales, and 25% of new heavy truck sales, by the year 2032. A thin and not very insightful op-ed in the Wall Street Journal made just such a case, adding a new error to the mix by assuming little progress in costs or adoption would take place over the next decade. While the op-ed discerns correctly that raising emissions standards more rapidly on ICE vehicles might lead to a market supply crunch rather than a successful transition (again, assuming virtually no progress in the learning rate of EV manufacturing) it completely misses the forest for the trees. The bigger, far more salient point is that relying solely on EV adoption just isn’t an effective way to lower emissions from the transportation sector.

Here, the word “effective” is meant to imply not just the volume of emissions we are attempting to curb, but the rate at which they are curbed.

The EPA’s proposal skirts the politically difficult problem of clamping down on the existing fleet by setting in motion aggressive emissions rules for new vehicles starting in 2027. In other words, the strategy is to realize emissions goals on the supply side of the new vehicle market. Automakers will be required to meet standards in their mix of both ICE and EV models offered. The new ICE vehicles will be required to have far lower emissions, and the EV models sold will, to put it plainly, need to be greater in number. This is a very macro approach, one that surrenders completely to the fact that any attempts to tax or curb existing vehicles is a third rail of American politics. But again, that surrender means moving any notable decline from transportation emissions to next decade. Indeed, in much of the EPA’s accounting, total volumes of emissions avoided are quantified to the year 2055. Well, yes, if you run these rules to 2055, avoided emissions will indeed be substantial.

So, we now have a policy proposal that gives up on a whole array of other curbs that could lower emissions sooner (and will still not avoid legal challenges, regardless), and, a not very helpful discussion that’s arisen around the proposal. Let’s make some corrections. First, the WSJ op-ed is the wrong way to come at the problem, and relies on a faulty assumption: that the EV adoption curve is neither strongly underway, nor will it be, regardless of additional policy. Plug-in sales in the US market last year (a market that’s historically been under-supplied with EV price range and model choice) reached 5.8% and is finally ready for takeoff. Even without new policy, EV market share in the US is fated to rise to at least 25-35% by 2032, and that’s pretty conservative. Let’s consider the following cases:

• EV market share in California: 2017: 4.2%. 2022: 18.8%.

• EV market share in the EU: 2017: 1.5%. 2022: 23%.

• EV market share in China: 2017: 2.7%. 2022: 25.6%.

The WSJ op-ed also inexplicably uses an IEA forecast that EV adoption will only reach 15% by 2030. Pro-tip: the IEA is terrible at long term forecasts, and any professional knows this all too well. Also, this 15% cited is likely the global forecast not the US forecast—though the WSJ Op-Ed authors, true to form, carelessly fail to make any distinction. Let’s assume it’s a global forecast, in which case, it’s just not relevant. We already know that large tranches of the world will remain way, way behind EV adoption. If however that 15% is meant to imply a US adoption forecast by 2030, well, that is just silly for a market already at 5.8% in 2022.

EV adoption in the US is going to go very well. It’s just not enough to bend emissions this decade.

There’s a fundamental blind-spot about using EV as the central tool for decarbonization and that of course comes via the lengthening average lifespan of existing ICE vehicles. The average age of US vehicles rose to a new record last year of 12.2 years. For a specific example, the top selling minivan in the US market, the Toyota Sienna, can now be run for at least 200,000 miles, and often lasts longer. Even if one optimistically projects that automakers hurriedly prepare today for these rules to land in 2027, notice again that the existing fleet of 275 million vehicles goes untouched. Accordingly, this requires that observers of energy transition in the transportation sector hold two, competing trajectories in mind: EV adoption rates can be rapid, but, the duration of the existing ICE fleet is so substantial that the decarbonization you expect simply doesn’t arrive at the same rate. And the corollary: EV adoption is an excellent method to start halting the growth of oil consumption. But if you are relying on EV alone to trigger petroleum demand declines, those will not come until much later when existing ICE fleets finally start to fade out.

The US has made no progress in reducing transportation sector emissions for twenty years. Unless there are new policies, The Gregor Letter expects no progress for at least another five years. Instead, we should expect that any sustained decline in this sector’s emissions will come next decade, not this decade. (clicking on the chart takes you to an interactive version).

Further reading: homepage of the EPA’s rule proposal, with links to its 758 page pdf.

Global electricity generation rose by a healthy 2.5% last year, and combined wind and solar covered 80% of that growth. The findings come from the annual Global Electricity Review, published by London-based Ember. Especially impressive is that combined wind and solar generation grew by 19%. That exceeded the trailing five-year AAGR (average annual growth rate) of 14.65% observed in combined wind and solar generation growth from 2016-2021. As the world electrifies, we can expect total demand to continue growing rapidly.

Unfortunately, coal generation also grew last year, by 1.1%, and according to the report, power sector emissions hit another all time high. While renewables+storage growth remains impressive, and perhaps will start to cover 100% of marginal growth starting this decade, we are still facing a problem of legacy generation, and the constraint it places on the effort to force power sector emissions into actual decline.

You are reading a free post from The Gregor Letter. There are very few of these, throughout the year. Why not become a subscriber? All paid subscribers get a free copy of the Oil Fall update package, and subscription rates are a very reasonable $80 per year, or $8.00 per month. Go ahead. Buy a ticket to the show.

If global generation growth from combined wind and solar maintains its recent pace through the end of the decade, peak emissions will be achieved in the power sector. But is that enough? The chart below applies the observed 14.65% AAGR in combined wind and solar generation growth during the 2016-2021 period to the remaining years of this decade. This is not a forecast. And it’s not a model, either. Rather, it’s simply a plausible case that allows us to think about how much work, at the margin of total system growth, combined wind and solar will do for us.

At first glance, it all looks so promising. For example, just reaching back to the findings from Ember—that combined wind and solar grew 19% last year from the 2021 baseline provided by the BP Statistical Review (2894 TWh)—suggests not only did growth last year reach 550 TWh in generation terms, but the 19% advance well exceeds the 14.65% growth projected here. That is awesome. Look at how far wind and solar are projected to grow, even at that lower rate.

Now comes the hard reality. The cautionary warnings made recently by The Gregor Letter about our current emissions trajectory are still relevant, even if the projection were to play out. The world as of 2021 generated a total of 28,466 TWh from all energy sources. If we apply an AAGR of 2.5% (the trailing ten year growth rate) to that figure, the world will generate 35,551 TWh by 2030. But look at where combined wind and solar land in the same year. In the projection, they grow generation at least 7000 TWh (2894 to 9970 TWh), almost exactly the same advance seen in the total, from 28,466 to 35,551 TWh. It is sobering indeed to think that wind and solar could both grow that strongly, yet still only cover marginal growth in total system demand.

In other words, we need combined wind and solar to maintain a very steep growth rate (and to plow through the constraints that typically slow grow rates) just to keep up with total marginal growth. Again, the two competing ideas: if wind and solar do cover 100% of marginal growth that is flat out amazing, and extremely good news. Yet, it still leaves the problem of existing generation, and legacy sources. As always, achieving peak fossil fuel consumption or peak emissions is a necessary, first order goal. But outright declines in fossil fuel consumption and emissions are harder to come by, because the task requires a two-front effort.

The bulk of the decline in US emissions the past decade was achieved through rapid coal retirements, but without a plan to curb natural gas growth, or to force oil consumption into decline, the trajectory of US emissions is no longer promising. The Gregor Letter apologizes in advance for harping once again on this topic, but there seems to be little widespread discussion of the fact that Paris 2030 emissions targets for the US are now totally out of reach. Not. Going. To. Happen. While the Biden administration understandably continues to cite those goals—a halving of total US emissions by the year 2030 compared to the 2005 high—it’s now time to fess up and acknowledge that, with 6.5 years left on the clock, these goals are no longer within reach. From 6007 million tonnes in 2005, to 3000 million tonnes in 2030? Nope. Not when we’re still hugging 5000 million tonnes in 2022-2023.

To be fair, some journalists correctly began to worry about the US emissions trajectory several years ago. Ben Storrow, of E+E News, made just such a case in 2020. However, other discourse continues to stray from reality. For example, New York based Rhodium Group at the end of March released a report on ways the US could still achieve its Paris 2030 goals. It’s generally good to be optimistic, and the Rhodium report is constructive. But, sometimes it’s equally important to be accurate, even if that means being pessimistic. The pathway(s) offered by Rhodium to reach 2030 goals are just not plausible.

Editor’s note: The Gregor Letter has turned decisively pessimistic in recent months around progress in emissions reduction for the simple reason that data trends lead inexorably to such a conclusion. This more skeptical viewpoint is also informed by observing over many years the amazing progress of clean energy, and how despite this progress, the “rump” of legacy energy sources and their emissions press onward. Fleets of newly built natural gas power plants are just like annual additions of new ICE vehicles to auto-fleets, extending the resistance to achieving emissions declines further out in time. To make this clear: if your primary emissions-fighting thrust comes mainly through the introduction of new technology, then despite how rapid that new technology spreads, you are still relying on a retirement schedule for all incumbent, legacy sources that is slow, and far more relaxed. Unfortunately, this is the path chosen when political constraints simply don’t allow for harsher emissions curbs. It’s also important to note that there’s an ongoing gap between the stated and revealed preferences of voters who identify themselves as being very gung-ho on taking climate action. Yes, they believe they want action. Until, that is, they are personally inconvenienced. Ask your own friends, who on one hand are certain climate action is necessary, how they would feel about a $15.00 charge every time they drive their ICE vehicle into the City of Boston, in addition to a tax that kicks in for every mile they drive over, say, 12,000 miles per year. For all readers who either live in Boston, or have in the past, here’s some on-point nostalgia just for you:

Readings of inflation confirm that the downtrend which began last year is still very much underway. And also, that the Fed should really, really stop hiking interest rates. The latest readings in CPI and PPI especially suggest that inflation’s arc continues to move in the right direction. Of course, even as some prices begin to fall, the stain of inflation remains visible across the world, like the high watermark left on buildings after a great flood. And that’s true also for renewable energy. Lazard, which produces an annual report on the cost of energy, revealed that for the first time in a long while, costs for solar and onshore wind rose. You can see that in the bottom two category boxes, in the chart below, which is extracted from Lazard’s 2023 Levelized Cost Of Energy+.

These cost increases would only be a concern if they developed into a new trend, and that is very unlikely. Indeed, as the learning curve presses onward, we should expect occasional breaks in the trend, before resumption of the grand descent.

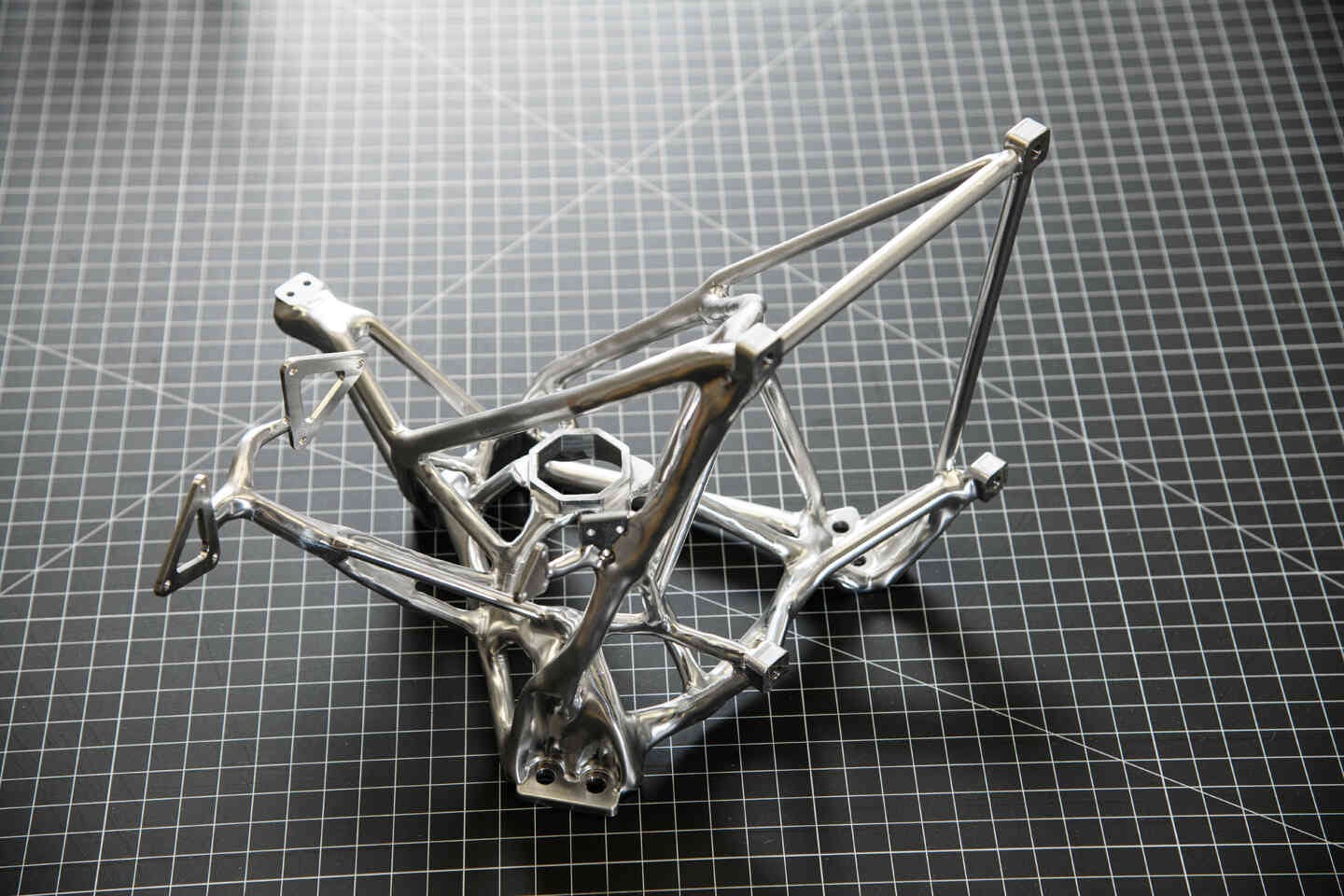

The latest tools of artificial intelligence are no longer mere playthings, but are swiftly entering industrial and commercial applications. Hype, as an accusation, is often used as an analytical shortcut to grapple with the new new thing. But hype is no longer even relevant when it comes to AI, because AI has gone feral. The New York Times had an excellent round-up of how AI is entering the workplace, and surely one of it’s most compelling examples comes from a NASA engineer, working on the development of mission hardware:

But where a human might make a couple of iterations in a week, the commercial A.I. tool he uses can go through 30 or 40 ideas in an hour. It’s also spitting back ideas that no human would come up with.

The A.I.’s designs are stronger and lighter than human-designed parts, and they would be “very difficult to model” with the traditional engineering tools that NASA uses. NASA/Henry Dennis

“The resulting design is a third of the mass; it’s stiffer, stronger and lighter,” he said. “It comes up with things that, not only we wouldn’t think of, but we wouldn’t be able to model even if we did think of it.”

Sometimes the A.I. errs in ways no human would: It might fill in a hole the part needs to attach to the rest of the craft.

“It’s like collaborating with an alien,” he said.

The Gregor Letter devoted coverage to AI back in early January, with a particular focus on the productivity potential, and its impact on the energy sector. | see: The Edge of Productivity, 9 January 2023. Because energy transition is ultimately an engineering and infrastructure project, readers are encouraged to ponder deeply the myriad ways AI could help speed our progress.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to Dropbox Shop.