Struggles and Setbacks

Monday 13 November 2023

The promise of small modular reactor technology was hit hard this month as NuScale, a Portland, Oregon based SMR developer, suffered a full cancellation of its first major project, located in Utah. Skyrocketing costs were the main cause, which in turn led the consortium of western utilities—lined up to purchase future power from the project— to back away. In coverage of the story, for example, Eric Wessoff of Canary Media notes that NuScale’s cost estimates rose sharply earlier this year, from $58/MWh to $89/MWh. More disheartening is that NuScale’s design had been approved the NRC, the only approval of its kind, so far.

The SMR approach to nuclear deployment was aimed specifically at bringing down costs through offsite construction, and its potential scaling effects. In the same way wind and solar power are largely manufactured offsite, and at scale, the hope was to realize a similar deployment sequence for nuclear: standardization of parts and equipment, and, onsite assembly. But even the best manufacturing learning-rate outcomes historically have always begun with high-cost early prototypes, and poor margins per unit until volume begins to rise. Furthermore, it’s far easier to eventually produce cost-decline effects when you are producing millions of simple units, like PV panels. When you are trying to produce the very first SMR, the challenge is exponentially harder.

Share prices of clean energy manufacturers have taken a beating in the second half of the year as rising interest rates take their toll. The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF, ICLN, is down roughly 30% year-to-date. Former high flying superstars like Enphase, SolarEdge, First Solar, and the giant lithium producer Albemarle have fared even worse. Broader markets meanwhile seem to think that interest rates have definitely seen their peak. But energy infrastructure companies across the battery, lithium, solar, wind, and EV space may need confirmation that the long-end of the interest rate curve has at least stabilized before investors are willing to return with enthusiasm.

The US offshore wind supply-chain is still being formed, and that’s one reason why we’re seeing project cancellations. While the US has done a great job so far of refurbishing ports, marshaling equipment, and even building a single fit-for-purpose ship, we are still at the very front-end of establishing the kind of resilient and efficient deployment system that Europe, by contrast, has enjoyed for years. Tactically, that means we don’t yet possess the kind of flexibility to dampen rising costs.

Unsurprisingly, these struggles and setbacks have delighted clean energy naysayers, whose pattern is well-established by now: for 2-3 year periods when clean energy is going gangbusters they lie in the grass, saying nothing. And then they spring forth, in a year like 2023. But strong trends are in fact built on the wrinkles of pullbacks.

As solar growth marches forward across the planet, one of the world’s largest countries, India, has fallen far behind. Despite India’s impressive electrification program, which has effectively brought power to previously unconnected populations over the past decade, the country is simply not taking advantage of solar, and its cheap & fast deployment. This is really bad. India’s population is set to overtake China’s this year, for example, and the country is now the #2 coal consumer. We simply can’t afford to have solar lagging in a domain of 1.4 billion people. Hence, the kWh per capita measure in the chart below best reveals the problem.

India represents therefore a very large block of current and future emissions from the power sector that is not decarbonizing fast enough. From a global accounting standpoint, this block joins another problem sector as represented by US transportation emissions from the existing vehicle fleet. Last month, at the Clean Power Hour podcast, I identified these two blocks as significant global impediments to getting fossil fuel consumption into decline.

The Israel-Hamas War has opened up faultlines within the Democratic electorate, raising serious and new uncertainty about the outcome of next year’s presidential election. Global sentiment is quite clearly on the side of the Palestinian cause. Measurements of sentiment however are complicated by the fact that a more generalized sympathy for Palestinians has been growing for years, and this is partly separable from where sentiment lies specifically on the events that began on October 7th.

Here in the US, sentiment is more equally divided—but not among young people and college students. They are angry, they are protesting, and they are now threatening to vote against Biden by simply not voting at all, next year. To complicate the outlook further, there are now at least four candidates that could collect votes from young people looking to protest current US policy (which they believe unfairly skews in the favor of Israel). Robert F. Kennedy, Cornell West, and Dean Phillips were joined this week by Jill Stein as alt-candidates that can be placed somewhere on the leftward spectrum. Ralph Nader has not joined yet (he’s now 93 years old) and probably won’t. But you get the reference: there are more than enough alt-names to produce outcomes similar to the year 2000 and 2016.

Editor’s note: because the Israel-Hamas War understandably generates passionate intensity, it’s important to clarify that this essay is not about the war itself, its adjudication, or the history that precedes it, but intends rather to exclusively address its political and cultural effects on the 2024 US election.

The 2020 election can partly be characterized as one where third party voting activity collapsed back from the high levels seen in 2016, in recognition that in an era of thin-margins, protest voting does not align at all with preferred outcomes. In 2016, a very large 5.7% of the national vote was distributed to candidates not named Clinton or Trump. In 2020, that share fell dramatically, down to just 1.8% for candidates not named Trump or Biden. The risk now is that this alt-vote share rises again next year. Should that happen, Biden’s exceedingly thin 2020 margins in Arizona and Georgia, where he won by just 0.31% and 0.24% respectively, could slip away easily.

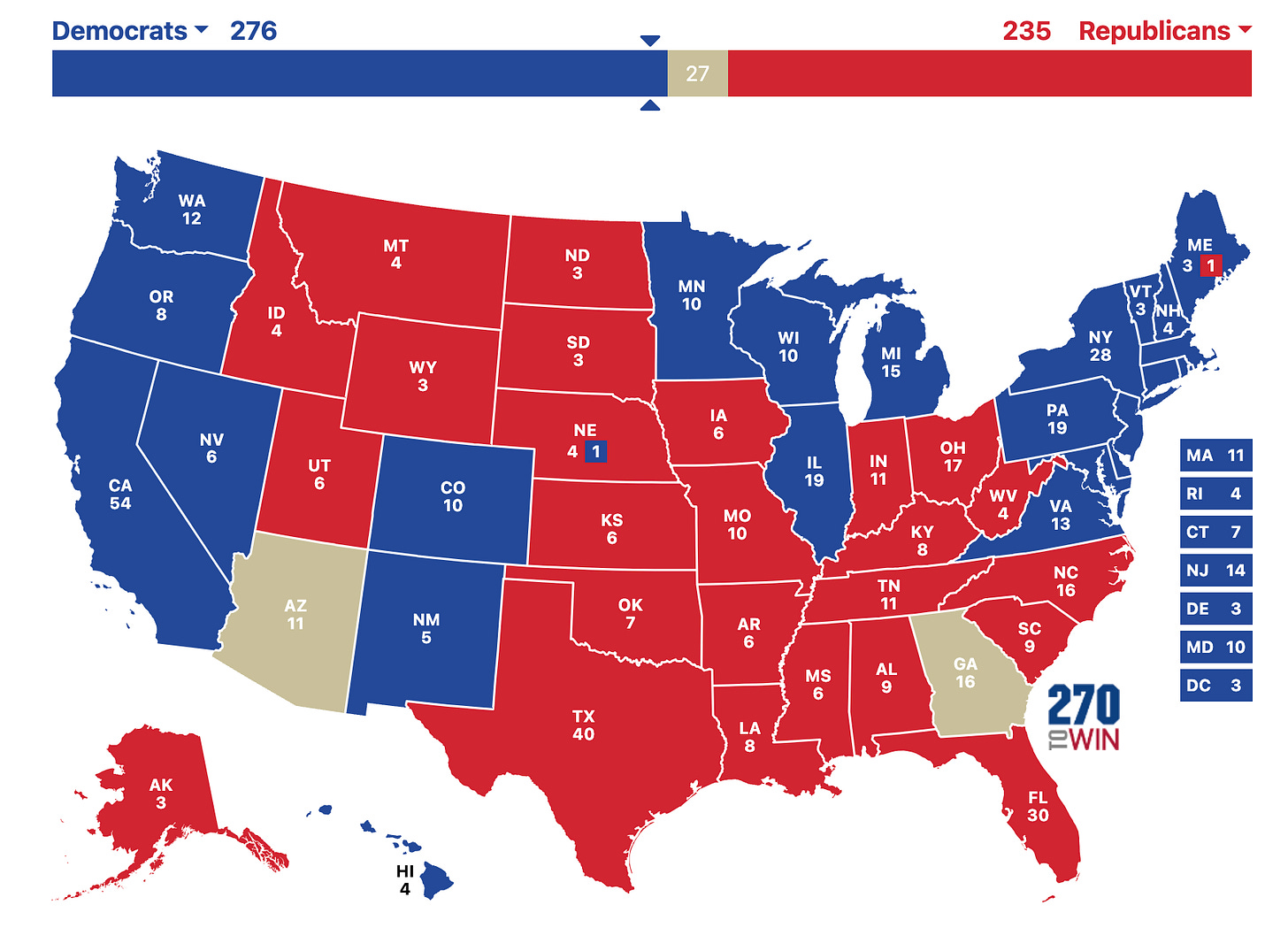

Below is the 2020 electoral vote outcome projected on the 2024 electoral vote map, with the only change being the removal of Arizona and Georgia from the Biden column to the toss-up column. Notice that by shifting just those two states to undecided, Biden’s EV count drops to 276, a paper thin advantage of just 6 electoral votes. In such a scenario, Biden could also lose Nevada, for example, and still win the presidency with the absolute minimum of 270 EV.

Unfortunately, it’s not necessarily Nevada that becomes the next risky state in 2024. Nor is it Wisconsin, which Biden also won narrowly by just 0.63%. Rather, it’s Michigan that suddenly looms as a problem for the incumbent given the very high Arab-American and Muslim population of the state. Rhetoric from these groups has been scathing the past month and yes, these groups were indeed Biden voters in 2020.

Flagging support for a Democratic candidate can develop into real trouble in Michigan. Let’s recall that in one county alone, Genesee, the losses that Hilary Clinton suffered in 2016 compared to Obama’s performance there in 2012 were more than enough to cause her to lose the entire state to Trump. It helps that Biden won the state by 2.8.% in 2020, giving him some margin to work with in 2024. And it’s quite unlikely that Michigan voters would actually vote for Trump over Biden on the specific issue of the Israeli conflict. But this doesn’t solve the problem for Biden. Remember always that because the electoral college skews in favor of Republicans, Democrats can only overcome this disadvantage by producing large turnouts. In 2020, the anti-Trump vote was in fact animated by Trump being on the ballot, and this negative energy is how Democrats not only won 2020, but have been putting together electoral successes since 2018. In 2024, it won’t be necessarily enough therefore for Trump to be hated however. That sentiment must be translated into votes for Biden, and not other third party candidates.

The Gregor Letter heads into year end with a number of baseline forecasts and outlooks in tow. Let’s list those now, in no particular order, and the letter will find a way to make these more readily available in the future.

• The growth of natural gas globally is being ignored, and it’s particularly worrying because so much of the capacity is new, and lays the groundwork for future dependency.

• The sector that is decarbonizing the fastest is global electricity. But even here, and even when assuming continuation of the frenzied buildout of wind, solar and storage, the prospect for declining emissions doesn’t really appear until the year 2030. Accordingly, if that’s the fastest timeline to emissions declines right now, what does that tell you about the prospect for declines of fossil fuel consumption and emissions outside of the power sector?

• The EV-only approach to fighting transportation emissions in the United States is seriously flawed, and even after considering those flaws the policy is risky too, as it depends on enough EV model choice and price range to induce fast adoption.

• If Republicans win the White House in 2024 it’s highly unlikely they will tamper with the existing sequence of legislation, from the Infrastructure Bill to the Inflation Reduction Act to the CHIPS Act, because these are disproportionately benefitting job growth in the red states. Where Republicans could do real damage to climate progress would come through relaxation on emissions reduction in transportation, adjustments to EPA policy and its power, and through stepped up efforts to protect coal, natural gas, and oil.

• Global oil consumption peaked in 2019 and will oscillate 1.00% - 1.50% around that level until a gentle decline sets in, perhaps by 2027. We should watch the US carefully here, as California petrol demand has finally entered decline after decades, and trends in the nation’s most populous state and leading edge economy are often a signal for the nation as a whole.

• Bouts of inflation across goods, services, and infrastructure do not change the primary trajectory of energy transition’s deflationary force. It is simply axiomatic that cutting down the volume of primary energy produced through combustion in favor of non-combustible energy will deliver an ongoing savings-dividend to the global economy.

You’d be hard pressed to find a more perfect illustration of a classic technology take-off point than the portrait of wind and solar in California’s electricity system. The often observed 5% market share level for this take-off is just picture perfect in the chart below: no progress, no progress, no progress and then boom! once the 5% share level is finally attained.

We cannot control the consumption of fossil fuels through supply side restrictions, but when it comes to American LNG exports, perhaps there’s an exception. As discussed in previous issues, now that the US is a net exporter of energy it is generally the case that fossil fuel supply growth from this point forward simply puts us further into surplus. In the case of oil, if we did not export petroleum products it’s a certainty the world would find supply elsewhere. But it’s not clear this is the same way to understand US LNG exports, and in particular, the prospective growth of future US LNG exports. It’s legitimate to ask the question whether the US, through its policy of expanding LNG capacity, is sending a signal to the world that it need not worry as much about natural gas supply. If so, that’s bad. And it could dissuade some countries from stepping harder on the wind, solar, and storage levers.

According to the EIA, LNG exports in 1H 2023 averaged 11.6 billion cubic feet (bcf) per day. That means we’re on course to exporting at least 20 bcf this year, as the chart from the EIA shows:

Now let’s review the scale and proportions of US LNG exports. At 20 bcf/day of exports, and 89 bcf/day of domestic consumption expected in 2023, natural gas exports are notching a level equal to 22% of domestic demand. That’s a big breakout from the 10% level observed over recent years. And that kind of marginal growth could indeed be expected to send a signal to the rest of the world that American LNG exports are rising and will continues to rise, as we have more than enough resource to use at home, and sell abroad.

A burst of productivity growth would be welcome, as it would add further downward pressure on inflation. While early, this appears to be unfolding now according to economists at Employ America, who point out that high levels of employment can indeed support an advance in productivity. US data showed that third quarter productivity made a large advance, growing at an annualized rate of 4.7%. The calculations are not complicated: when GDP grows far more than the labor force required to create it, voila, productivity expands. That slowing growth in the labor market is also connected to the emerging view that the Fed is not merely done, but done for good raising interest rates. And now markets have flipped their focus, and are thinking about when the first rate cuts will come in 2024.

—Gregor Macdonald