Supply Lines I

Monday 4 October 2021 | Part I

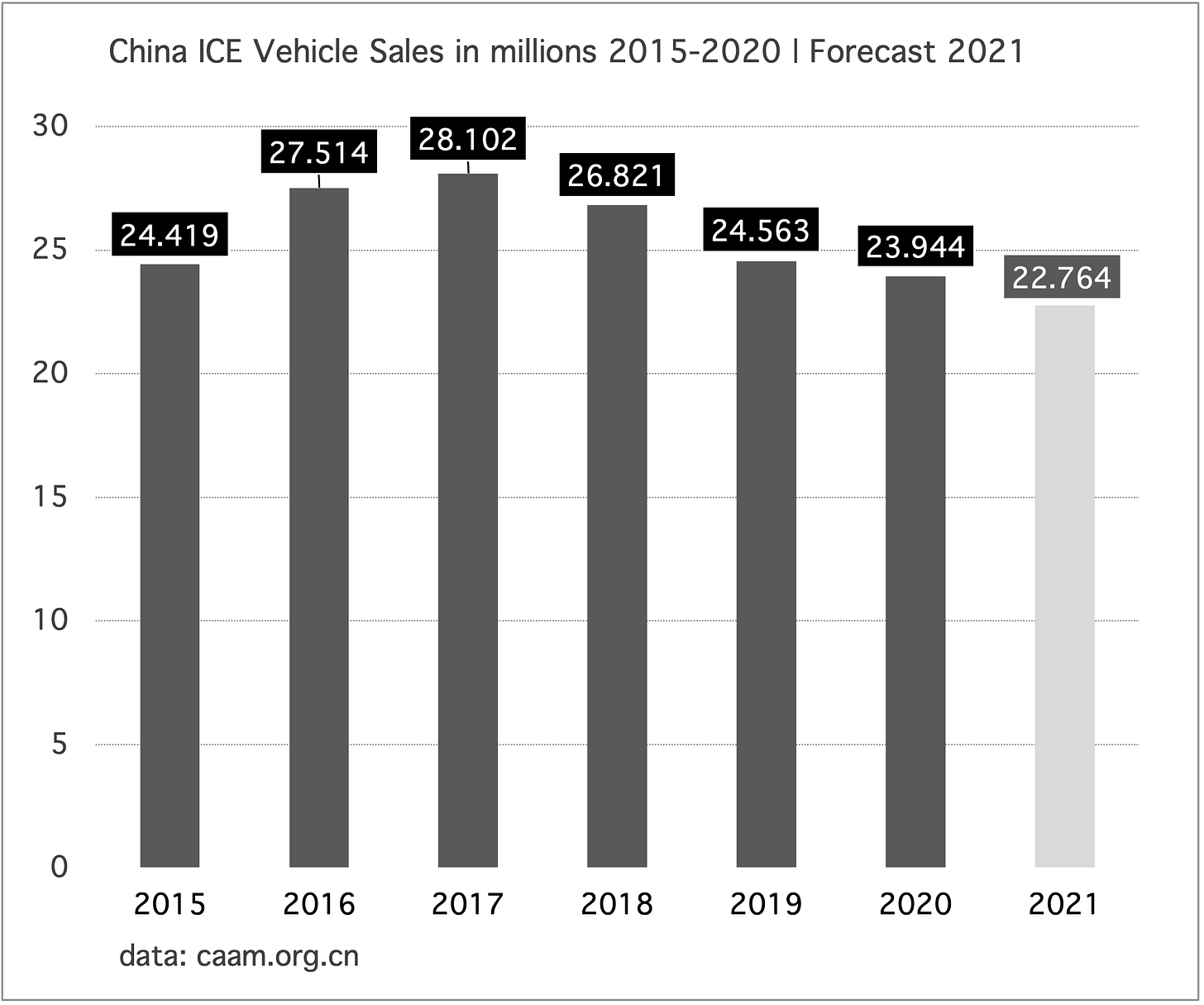

There are good reasons to forecast that global oil demand has now entered a plateau. Let’s start with a big one: the peak in global sales of internal combustion (ICE) vehicles, set back in 2017, triggered by the world’s largest car market, China. Since that time the main tracking agencies, IEA and EIA, have converged to forecast that global road fuel demand is also now peaking. While global demand for crude oil will not make it back to the 2019 highs this year, the same agencies believe it will touch those levels next year. Sure, maybe that happens. But there is little in the economic outlook or global demand structure to suggest we will exceed the 2019 highs by much, or for any length of time. The post-pandemic period is also playing a role by opening up the door—and keeping it open—to remote work. Will the bulk of workers eventually go back to the office? Of course they will. But will enough workers transition to new office/home schedules to further blunt petrol demand? Yes they will.

The news that global ICE vehicle sales have peaked still surprises many, even as that tipping point occurred almost five years ago. In China, the peak now looks rather dramatic. Data for this year conforms to the trend, with ICE sales on course to fall to a multi-year low. EV are now in total control of China’s car market.

Soaring prices for coal, natural gas, and oil give the impression that a new round of fossil fuel adoption is underway. Instead, price volatility is actually a feature of fossil fuel demand growth entering a plateau. Since the 2014 peak of global coal demand, for example, price spikes have beset the international coal market as logistics and supply lines have become far less liquid. Oil now joins coal as the latest energy source to both enter a demand plateau, while suffering the effects of ongoing underinvestment.

Global oil companies did not make a mistake in devoting less investment to the development of new oil supply, over the past five years. The withdrawal of these investment flows are best expressed through the price performance of the oil and gas services sector, which is down a rather intense 80% since 2014. Why did oil companies start reducing their bet on the future? Why did the supermajors, as some analysts have correctly pointed out, choose a form of self-liquidation? (If you are not replacing your oil reserves with new supply, then you are functionally making a business out of reducing inventory).

The answer lies in the declining rate of demand growth for oil. In the latter half of the 20th century, every new unit of GDP required new units of oil consumption. In this century, that relationship has largely broken down. Analysts noticed. OPEC noticed. Oil companies noticed. Perhaps the only group to consistently deny this truth has been oil and gas focused fund managers, who have relentlessly carried the torch for the sector despite the ongoing contraction of exploration and development.

The ironies abound. Only one year after British Petroleum declared in 2018 that global oil demand would grow at a nice, moderate pace for decades to come, the London based group put out a 2019 forecast essentially admitting that after 2025, demand growth to the year 2040 would be close to nil. This forecast occurred before the 2020 pandemic. In BP’s latest outlook, global oil demand now declines outright from 2025 to the year 2040 in its “business as usual outlook.” In other words, in a world without new climate policies, BP sees the oil business entering long term contraction regardless.

If BP is roughly right, that global oil demand even without new climate policies is set to decline from 98 million barrels a day (mbpd) in 2025 to 94 mbpd in 2040, then oil price spikes will become more commonplace and more severe. Moreover, you can also apply these dynamics to ICE vehicles and all the associated existing infrastructure currently in place to serve them, from oil-change services to parts manufacturing, and of course petrol stations.

Natural gas meanwhile is in a slightly different position to both oil, and coal. Globally, natural gas doesn’t face a demand growth problem that is imminent. In addition to a large dependency in residential buildings that’s been erected not just in the US and Europe, but also in China, natural gas has a number of harder to abate industrial applications that are likely to be supportive of further demand growth. But everyone should be aware that North America has mammoth economically recoverable reserves of NG. A fact acknowledged just this week by Bloomberg:

It was inevitable however that US natural gas prices would begin to be determined by global demand after the US unlocked its market to the world, through the advent of LNG export capacity. This is actually a good thing. And it’s especially good from a climate perspective. Were there no export capacity, US NG would remain not just landlocked but grotesquely underpriced, compared to world prices. What effect did this underpricing have the past decade? That’s easy: huge, new adoption of NG into the US energy system. Between 2010 and 2020 US demand for NG grew by a gargantuan 26%, from 24,087 to 30,482 bcf.

Let this be a lesson therefore to those who are inclined to believe that restrictions on global trade, or policy-pressured pricing schemes, are a good route to the suppression of fossil fuel demand growth. A basic framework: government sponsored incentives to adopt new technologies that promise to be cleaner, more efficient, and that remove “externalities” from the system usually pay off, and pay off handsomely. But price controls on resources tend not to work out well, and often unleash blowback in various forms, among other unintended consequences. In other words, if you are looking to see coal, natural gas, and oil removed from the system, halting their exports probably comes bundled with a price suppression scheme that simply makes them underpriced, and therefore ripe for further adoption.

What you want to see therefore are higher prices for fossil fuels. Better still, price volatility. Both phenomena will curb, if not kill adoption and will blunt further demand growth. Morgan Stanley, for example, in a note to clients this month correctly forecasted that increasingly high oil prices would lead to demand destruction. Now ponder that concept as you read a brief wrap-up on last week’s prices in global energy.

What do you suppose will be the reaction of both the public and policy makers to a looming supply crunch in global energy, as the northern hemisphere heads into winter? We should remember that this is the year in the US that a number of new EV models land in showrooms, and that in both China and Europe EV availability is broad and deep. In Britain, the volatility in petrol prices is compounded by a trucking shortage which unleashed a buying panic as petrol has not been adequately distributed throughout the country. You would expect to see this therefore…in fact, this exactly:

Global shortages of fossil fuels are likely to persist through winter, because reserves and storage are not meeting requisite levels here in early Autumn to calm futures markets, where prices are set. The natural gas supply problem will be hardest to solve, in the near term. It’s not that US natural gas storage levels are especially concerning, not at all. But rather, that the marginal call on US natural gas through US LNG exports is so strong. Oil, by contrast, can be solved rather easily as OPEC is estimated by EIA to be sitting on an enormous 7 mbpd of spare capacity, which is forecasted to only drop to 5 mbpd by next year. Without this spare capacity, futures markets probably would have pushed oil prices to even higher levels by now. As we head into winter, therefore, keep something in mind: the media will likely do a terrible job, conflating distribution and supply-chain problems in petroleum products with soaring demand for oil. Mostly, every fossil fuel will be bundled up in news coverage into a rather unwieldy bolus, implying that global fossil fuel demand is going through the roof. That’s a story the media loves to tell. But always remember the difference between rates, and levels.

You are reading a two-part free post from The Gregor Letter. Part II will publish next Monday, 11 October, between the dates of the regular publishing schedule. If you are still carrying a free subscription to the letter, please consider subscribing. Here’s why: there are very few free posts throughout the year. To learn more, see the About section. Many thanks as always to the international institutions, agencies, and investment professionals who rely on the letter for its energy and climate analysis.

The global call on natural gas has repriced North American natural gas, through the mechanism of US LNG export capacity. While the US exported small volumes of NG by pipeline to Mexico in the years leading up to LNG capacity deployment, this did not exert any discernible price pressure. But US export capacity, after the latest additions and expansions, has now risen to an impressive 10.8 bcf/day, according to the latest analysis from the EIA. Moreover, LNG exports are soaring after a slump in 2020, and hit a record high in the first half of the year, averaging 9.6 bcf/day. The US is therefore exporting pretty close to capacity, as you can see in this chart from EIA:

Fossil fuel price volatility and a shortage of fossil fuels utilized in power generation are likely to be supportive of wind and solar growth. Wind and solar don’t need any particular help right now, by the way. Growth globally is absolutely off the charts. Accordingly, it was inevitable that panel makers and other electronic equipment makers would finally get some pricing power. And that’s now happening, as prices firm. It’s also worth mentioning that outside the OECD, where construction permitting can be less onerous, utility scale solar can be mounted at a fairly high speed. Both China and India have thrown up arrays of very substantial size on tight timelines, and if natural gas and coal availability issues persist, 2022 could be spectacular for solar growth. The moment is worth savoring: an energy crunch that likely accelerates existing wind and solar plans, and moves future plans forward.

China ordered energy firms to secure supplies, at all costs. The directive added fuel to the unfolding energy supply shock now rippling through the world economy. While troubles in China’s real estate sector largely animated market concerns just a few weeks ago, the risk that China and other manufacturing centers do not obtain adequate supplies to maintain output is probably more serious, and worth a stepped up level of concern. After all, the state can nationalize or bail out failing companies, and conduct monetary operations to smooth disruptions. But no amount of fiscal or monetary effort can magically conjure energy supplies. Coal is either on its way to you by ship, or it isn’t.

The race continues to lock down future battery production capacity. The scramble to adequately supply future energy demand is also taking place on the energy-transition track, as automakers now rapidly shift to the electric drivetrain. Volkswagen boldly secured capacity earlier this year, buying up all of Northvolt’s future capacity (and then some) for the next decade. Now comes Mercedes-Benz in a new, European based battery venture with Stellantis. As part of the deal, Mercedes will take a 33% stake in battery maker ACC. But the blockbuster announcement of the week surely goes to Ford, where interest in the all-electric F-150 is running at a fever pitch. The company announced plans to build several battery production plants in the US South that would require the hiring of 11,000 workers.

Blame for global energy shortages is fated to land on climate policy, and ESG investing. And, there you have it. But the pathways to eventual trouble in global coal and oil demand were set years ago. Coal in the US for example was doomed by an aging fleet due for retirement, and the advent of cheap natural gas. Coal growth in China ran into political and cultural trouble starting over six years ago, when the populace reached its max tolerance threshold for polluted air. Wind and solar learning rates and cost declines also started crossing economic bright lines as early as 2010. Warren Buffett bought big solar as early as 2014, when “climate policy” was still largely theoretical in the US. And Buffett got to work building out massive wind capacity in the midwest shortly thereafter. Again, fairly basic wind and solar production tax credits that go as far back as the previous decade were all that was required.

Rather than being premature, climate investing and ESG has blown up only recently into something bigger, and is hardly the driver of current fossil fuel energy shortages. US automakers are late, not early to the EV game. US oil production has gone gangbusters all decade, only running into trouble during the pandemic. No, it’s the pandemic and its aftermath that are driving current shortages. The pandemic retains financial-crisis characteristics, dynamics that make supply crunches inevitable. Did climate policy and ESG investing create shortages in lumber, semiconductors, used cars, oddball foodstuffs, iron ore, and copper? Of course not. Rather, it’s the rate of demand change, which typically skyrockets off an unusually low demand bottom after a financial crisis that’s driving shortages. We are clearly entering, however, a volatile period in which the current industrial base will be asked to serve two masters: the previous system, and the one being born. That’s not easy. And it will produce endless and competing explanations for how we got here, and where we are headed next.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.