The Big Number

Monday 10 July 2023

Excitement at the raucous growth of global wind and solar is well justified, but their growth rate alone is not the only number that matters. Just released annual data from EI Statistical Review shows the trailing five year growth rate of wind and solar generation has bumped up again, from 14.7% in the previous period to 16.6%. That’s awfully impressive given that both technologies have been scaling hard for a while, since 2010. Now, from a bigger base, wind and solar have added an incredible 514 TWh, advancing from 2913 TWh in 2021 to 3427 TWh in 2022. Some context: the United Kingdom, with a population of 67 million people, consumed just 326 TWh of electricity last year. When you start growing new power supply in volumes that exceed the power needs of whole nations, you’ve hit the big time. Solar in particular has entered a kind of insane mode, as PV production capacity explodes, and is expected to wow the world the next several years. And offshore wind—which captures far more plentiful wind supply—is also driving growth and it too will throw off amazing gains in the years ahead.

Let’s take a look at how that growth may play out. While the chart below may seem like an example of irrational exuberance, the projection to the year 2030 simply applies that 16.6% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) to the final seven years of this decade. Yes, The Gregor Letter is well aware of the classic constraint that reliably sets in eventually, curbing growth rates as the underlying system grows larger. Got it. But the growth rate slowdown of wind and solar generation probably doesn’t come until next decade, as many domains across the world are still just getting started and costs for wind and solar continue to fall—not always smoothly, there are bumps—but adhere to the trend. The result: it’s quite plausible the two electricity sources, working as a team, triple output by 2030.

It’s easy to be swept away by such projections, and it’s further tempting to become bullish about wind and solar’s ability to finally eat into existing fossil fuels in global power. But it seems of late that there’s another number, a much bigger and perhaps more important number, that is insufficiently addressed: and that’s total demand in global power. And in particular, its growth rate.

Advocates of clean generation growth chant a mantra: electrify everything. That’s rational. Wind and solar are wildly efficient compared to fossil fuels. And the more you install them in global power, the more efficient global electricity becomes. From a macro view, this is not only the heart of the current energy transition, but the process portends a kind of deflationary boom, in which the cleanest energy is the cheapest, and can be added quickly as demand grows. It is after all the open declaration of transition to move everything, from transportation to steelmaking, over to the electrical grid. The energy savings will be enormous, freeing up capital along the way that will keep the process moving forward. But there’s another outcome to consider: big growth in global power.

How shall we model that total system growth? For example, if we take the trailing ten year CAGR of global electricity, currently at 2.5%, and project this forward, then last year’s 29,165 TWh generated will grow to 35,551 TWh by 2030. The system itself, growing at a lower rate from a much higher base, advances by 6,386 TWh. Wind and solar meanwhile, using the projection from their own chart, advance at a high rate from a lower base, growing by 8,237 TWh. And voila—happy news—wind and solar would not only cover all marginal growth in the system, but would finally eat into underlying fossil fuels. But so much depends on that system growth rate. And 2.5%, over the past decade, is probably too low for the decade to come.

Before we test out a plausible growth rate for the system to the year 2030, let’s take a quick glance back at global power over the past decade, and set it against the former gold standard of economic growth and energy adoption: oil. During the 20th century, the correlation between marginal growth in oil demand and economic growth was very tight. Annual oil demand (and remember, much of this demand growth was fresh adoption of oil) typically ran at 2% and often higher, at 3% or more as oil replaced coal as the world’s number one energy source. By the early 1970’s, oil was so mighty it accounted for a full half of global energy demand.

But oil demand growth has slowed way down the past decade or so. In each of the past twelve years, for example, global growth of electricity demand has outpaced oil demand in all but two of those years, 2015 and 2022. As The Gregor Letter has pointed out since forever, economic growth itself is now more linked to power system growth, rather than oil demand growth. Indeed, that’s not a bad description of the 21st century vs the 20th.

Now comes the hard part: forecasting a more plausible growth rate in global power. Remember, the stated intent is to move as many processes and services as possible over to the grid, a project that will roll out over the next 30 years. In no particular order: Cars, trucks, and buses. Steelmaking and other manufacturing. Heat in all buildings, everything from private and government offices to schools, and domestic architecture. Aviation, not long haul carriers, but short-haul flights powered by hydrogen (made with electricity) and of course smaller air-devices like drones. The entire hydrogen sector, which proposes to migrate away from natural gas or coal to electricity, including industrial turbines that can convert from natural gas to hydrogen blends. And then data—not just existing data centers which are already multiplying steadily—but the emerging set of demands from AI training, and provision. Some have claimed that a single Nvidia A100 will consume around 3500 kWh per year. Well guess what, that’s not far from the energy needs of a single EV for a year. While we have to assume efficiency in computing will also make some advances, it seems that overall we’ve not quite fully envisioned what it means to 1. move work done currently by oil, coal, and natural gas over to the powergrid. 2. to chase that transition with clean sources while the system itself is growing strongly, precisely because we intend to exploit the grid as a platform.

Let’s think about system growth in four scenarios to the year 2030 in global power, using CAGRs of 2.5%, 2.75%, 3.00%, and 3.25%:

Holding combined wind+solar growth to our previously estimated constant advance of 8237 TWh by 2030, we see that if total global power demand grows by 3.00% or less, then wind and solar not only take control of all marginal growth, but they exceed total system growth which means they will cut into all resources ex wind+solar. We can’t know how each energy source ex wind+solar will fare with any specificity. We hope wind and solar will kill coal and natural gas, and won’t kill nuclear and hydro. The outcomes will vary from domain to domain. There’s still more coal to kill in the US, and still more natgas to kill in the EU. We shall see.

In the fourth scenario, however, where total system growth runs at 3.25% to 2030, combined wind and solar only cover marginal growth, leaving all current energy sources undisturbed. There’s even a small deficit in this scenario, probably filled by natural gas.

Does The Gregor Letter lean towards any of these outcomes? Yes. Here is the thinking: global power demand has been growing already by a 2.5 % CAGR over the past decade. When the global economy adopted oil, annual growth rates were at least that much, and often more. Therefore, grid growth is certain to lift off from the trailing 2.5% rate, making its way to 3.00% and above. We will see a blend of rates of course to the year 2030. But it seems prudent to conclude the following: even at very high rates of global solar and wind generation growth, there is not a good prospect until next decade that they cut into legacy sources in global power. There are many moving parts to this equation. But keep your eye on the big number.

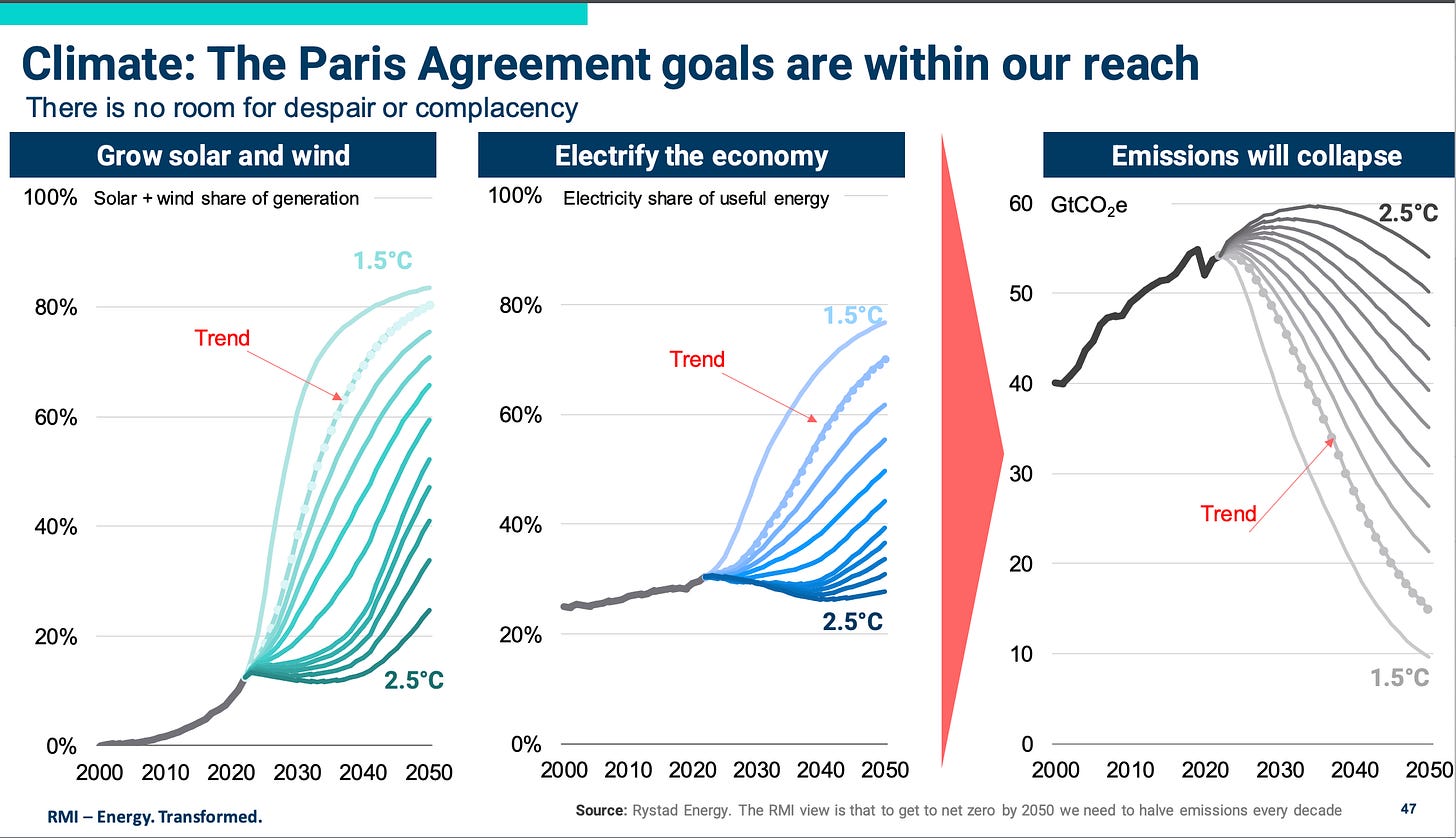

Rystad Energy and the Rocky Mountain Institute are projecting that, based on current trends, global wind and solar could reach a 40% share of global power by 2030. This is probably not a forecast. But is it possible? Well, just using the scenarios already laid out here in today’s letter, a 3.00% total system growth rate to 2030 would see wind and solar reach a 31.5% share of total global power (11664/36949 TWh). Even the slowest system growth rate of 2.5% would see wind and solar reach just a 32.8% share (11664/35551 TWh). It must be pointed out: the wind and solar growth projection offered today in the letter is pretty aggressive. Consider as one example that the projection already shows a 1000 TWh advance in generation in a single year, from 2026 to 2027. And overall, a full tripling (if not a tad more) of wind and solar generation over 7 years, from the current base, is hardly conservative.

In the RMI Renewable Revolution slide-deck (published June 2023, opens to PDF), solar and wind reach a 40% share of power by 2030 and a 70% share by 2040, based on Rystad’s assessment of the current trend. But it must be pointed out: only when we combine a lower growth rate to the system, while maintaining the high growth rate for wind and solar, do we start to dislocate emissions, forcing them into decline. Indeed, this is the growing concern expressed in The Gregor Letter quite repeatedly this year, as we watch natural gas continue to make very strong gains in global power because wind and solar are not yet keeping up with total growth.

Let’s end on a note of optimism: eventually, transitioning to electricity means the global economy will need less energy to accomplish the same tasks. There’s an intrinsic efficiency gain embedded into this process. We will harvest it. But the other side of this view is as follows: if you agree that the future trajectory of climate change is profoundly altered by what we accomplish, or fail to accomplish, in the near term, then you really don’t want to push out emissions declines in global power until next decade—even the start of next decade. As The Gregor Letter pointed out in the previous issue, the next three years according to the IEA may actually see no emissions growth as nearly all system growth is covered by renewables, hydro—and nuclear. That’s great. But what we are seeking are emissions declines. Everyone needs to think harder and more often of the plateau problem, and how the generalized forces of growth make it challenging to reach the escape velocity we need to eat away at legacy sources.

Global emissions from energy consumption reached an all time high last year. This is especially disappointing considering that neither oil or natural gas consumption got back to their own highs (oil, 2019 and natural gas, 2021). The culprit was of course coal, which has been recovering of late and actually crawled back to match the all time highs of consumption first set in 2014. Ugh.

Canada announced its intention to deploy small modular nuclear reactors. We shall see, right? Nuclear has not fared well in the OECD. But the province of Ontario, which already has one SMR planned, is now going to adopt three more. Completion times are slated for the 2029-2036 timeframe. As others are more frequently pointing out, we will need lots of clean energy next decade, and while a global rush to complete more nuclear by 2030 would be optimal, we have to take what we can get.

Canada is choosing the Hitachi/GE BWRX-300, which has recently gained interest from a number of domains. That “300” number of course refers to the nameplate rating, of 300 MW. Yes, that is small. But remember, nuclear power has an exceedingly high capacity factor. Should Canada build all four, that 1200 MW of clean power doesn’t need to be deflated, like wind and solar, to calculate its annual generation. On land, windpower would require roughly 3X as much nameplate capacity, 3600 MW, to produce an equivalent amount of power. Oh, and by the way, Canada should absolutely be building tons of solar, wind, offshore wind, and batteries in recognition that they are the fastest means to decarbonize.

The release of the latest Statistical Review of World Energy from the Energy Institute has sent data-and-graph junkies into happy orbit. In case you didn’t know, British Petroleum handed off the annual review to EI, also based in the UK. One of the more comprehensive charts spotted is from Grant Chalmers, based in Brisbane. Well done, Grant! The room for myriad countries to grow wind and solar is ample.

An emerging theme right now is the continuing strength, and falling inflation, of the US economy. Indeed, one might call it a recognition phase, as a number of worries from the past several years finally begin to recede. While today’s politically polarized culture sadly filters such trends through a partisan lens, it might be good to briefly stand back and ponder the situation. Here’s a thought: is there an echo in US economic strength and domestic investment starting in 2022, in the policies and outcomes that were enacted in 1980-1982? Many people today still regret deeply the policies of Reagan and Thatcher but it’s not exactly naive to acknowledge that both economies had come through terrible times and were not set up well for further growth when those two figures came to office. The political left was deeply critical of those policies (and may still be, today) but there were indeed a number of protected industries in Britain and some very bad regulations and tax rates in the US that had probably reached diminishing returns.

Today, free-market adherents are aghast at the US for how much we are investing in ourselves. But that decision has attracted enormous flows of inward capital looking to join the party. Indeed, we’ve actually got a jobs boom in many southern US states that have not enjoyed such growth in a long time.

Economic history suggests that sometimes you have to turn the tables over, and go against theory. Depression era policies by FDR were considered totally nuts, at the outset. Indeed, there are people today who still think so. But those policies caused US GDP to skyrocket, and got capital flowing again into the economy, before the relapse of 1937. The era looks like one of those classic moments where “the theory says this can’t work” and yet it does work.

There are those today who are concerned that re-shoring may lead to redundancy, or other problems that typically arise when government steps on the scales. I would remind readers that much of what is being built today: chips, batteries, EV, transmission equipment, and hydrogen capabilities are all leading edge technologies that the world will need for decades to come. Moreover, one of the historical advantages that China lorded over the rest of the world was cheap electricity, but the US now has very competitive rates for commercial and industrial electricity. No surprise. Yes, US wages are still higher of course than in the Non-OECD. But part of the social dissatisfaction of the past 30 years has been that wages have not gained along with productivity. Current policies are at least interrupting that downward trend. And, by the way, China still manufactures the bulk of new energy equipment and technology. Re-shoring, while often made out to be a huge deal, is small. But it feels big because this is indeed a new direction in US policy—industrial policy.

Solar PV, batteries, and chips will be made in Asia for a long time to come. Ricardo acknowledged that the country that’s better at designing something like an Apple phone or an Nvidia chip, as we do, may also be a country that cedes the bulk of chip manufacturing to other domains; but can still make some chips at home too. It’s not an accident that a battery maker like Form Energy chose West Virginia to site their production, for example, because it must be pointed out that vast tracts of the US are extremely poor, impoverished even, and sit in the shadow of the long-faded ghost buildings, canals, and infrastructure of a 20th century industrialism long gone by.

In 1980, whether you like it or not, US tax rates were way too high and bringing them down was a positive. Eventually though, the return on tax cuts diminished, then disappeared. Tax cuts are pointless now in the US. We have not gained from them in a long time. The 2022 echo to 1980-82 therefore zig-zags in a completely different direction. And just to point out: Republican electeds are not unhappy to see such investment pouring into their states. Indeed, for thirty years there have been bi-partisan murmurings that the US needed to engage in some industrial policies as our cities and manufacturing jobs hollowed out. Critics might pause, therefore, before leaping in too fast and consider the simplest proposition: this is what the country wants.

—Gregor Macdonald