The Edge of Productivity

Monday 9 January 2023

A broad advance in productivity led by AI would have a profound effect on the energy sector. Despite the propensity of culture to fall in love with the prospect of technological miracles, the speed by which active AI capabilities are currently being rolled out suggests that years of investment in deep-learning are coming to fruition. ChatGPT for example, a branch of GPT-3, increasingly looks like the front end of a potential long wave, one that begins with a simple interface that everyone, from a child to an adult professional, can utilize. ChatGPT is already performing as a code editor, an idea generator, and a writing organizer. No, it’s not merely a fancy search engine. And further iterations are coming. OpenAI, which released the current version in early December—the version that has so many legitimately excited—is likely to release yet another version, GPT-4, in 2023. The scope of that version is expected to be impressive.

The energy sector of course has always been inextricably tied to the field of engineering, and with respect to fossil fuels, geology. But as with all other sectors, technological advances aid and abet. A simple example would be that at the beginning of the fossil fuel age, exploration exclusively took place on land. Today, satellites or other aerial vision technologies can more efficiently identify deposits. A company like Schlumberger—which provided comparatively simple services to the oil and gas sector in the 20th century—must really now be thought of as a technology company.

Indeed, it’s the capital intensive and deeply physical nature of energy production that makes the sector such a reliable consumer of any new techniques that would lower costs. Digging, shipping, and burning (combustion) are expensive. You’ll gladly take any help available.

Let’s pause here and reflect that OpenAI is already in talks with Microsoft, which is reportedly looking to incorporate its capabilities into its Office suite and its own search engine. Microsoft made an investment in OpenAI in 2019. Speculation is running rampant, meanwhile, as to how far AI capabilities are also being developed at Google, Amazon, Apple and other tech giants with deep R&D teams backed by mountains of capital. Typically, breakthroughs come in clusters as disparate teams working on the same problem arrive at thresholds, not at the same time, but within close proximity to one another. This is a way of suggesting that if OpenAI is now reaching major rungs on the AI ladder, others are likely nearby, and we’ll get confirmation of such soon.

Prior to these new offerings from OpenAI, deep-learning researchers were already peering around corners, looking at ways to optimize wind and solar output. Better weather prediction is an obvious goal in renewable generation, for example, because there’s money to be saved in the economics of the electrical grid if two and three day-ahead conditions are better known. Remember, the gains from these kinds of strategies are not necessarily zero to one gains, but instead pursue incremental improvements that are slow and steady. They add up.

So, AI capability is not only leaping quickly from deep-learning development to a friendly, consumer-facing portal, but it’s leaping right into commercial applications. There is also a viral, entrepreneurial pathway that’s getting started as everyone from classroom teachers to corporate workers are reporting that ChatGPT has already arrived, and is finding a place in their workflow. Not to suggest that individuals are front-running the Microsoft-Open AI partnership, but the fact that a lone person can achieve integration of ChapGPT with Excel and Google spreadsheets is your warning that the tool is so readymade for use that leaps forward can plausibly come not only from large teams, but lone individuals. Again, culture has many mythologies about the tinkerer. Those mythologies arise because sometimes it’s just plain true.

New energy is of course everywhere and at all times a form of infrastructure, and that means computer aided design, location siting, materials usage, and optimization are the edge tactics that lower costs, and keep the learning curve pressing forward. First Solar, for example, has put considerable effort over the years into panel size so that, in an example of containerization, the panels First Solar produces dovetail perfectly with the installation process, thus lowering deployment costs, and timelines.

It’s not just tantalizing but legitimately exciting to consider what AI could do for research and development in renewables. Solar panels, wind blades, superconductivity in transmission, longer-duration energy storage, and material science are all obvious areas where merely the speed of research using current tools could be transformed. Monte Carlo simulations, for example, are widely used in utility planning. What are the implications if the ability to build and run those models, apart from any magical breakthrough, not only gets faster, but expands to new users? AI promises to democratize access to higher level analysis.

The systemic potential of AI is already in the hands of economists. The team cited in the tweet thread below, from MIT and UCLA, are looking for the possibility that deep learning, adopted in the R&D sector, could nearly double the productivity growth rate in the US. You can read their paper here, but I highly recommend the full thread.

Shortly after the great recession, Northwestern University professor Robert Gordon questioned whether US economic growth was mostly over. More broadly, Gordon wondered if 20th Century scientific progress, which advanced at a ferocious rate early in the century, had greatly slowed down. Refrigeration, electricity, flight, telecommunication, and the internal combustion engine—what happened to breakthroughs like those? Gordon asked. Those were legitimate questions, and Gordon made good points. At the time, the best answer to his probing was that progress, and its fast rate, would come around again. But of course, no one could be sure.

The Gregor Letter is very anchored to energy history. Some transitions, like the migration from wood to coal, are raw but straightforward phase transitions in which a new, extractable, energy-dense resource essentially blows up the existing regime with an almost bellicose release of pure power. Others, like the transition from coal to oil, segue more smoothly from the previous regime, and in the case of oil, introduced liquidity in both a literal and an operational sense. Under oil, the existing world started moving faster.

The current transition is very much about chemistry, material science, physics, engineering, and gaining small edges that can be replicated easily. Solar panel efficiency languished at low levels for a long time. Now, as it moves higher, other players add sizing or utilization advances to secure gains. At one time it would have been too expensive to install solar arrays that tilted, turned, and oriented to the movement of the sun. Today, there are growth companies based around such capabilities.

Unlike fossil fuels, wind and solar are not energy dense. Rather than being energy sources themselves, they are instead energy capturing devices. At first glance, they seem weak. But then, as they fall in price and expand like an army, the truth comes through: they are titans of efficiency. This is the perfect type of hybrid infrastructure to be guided by science. It is time to take AI’s potential impact very seriously.

Further reading: The Third Magic, a meditation on history, science, and AI.

You are reading a free post from The Gregor Letter. All paid subscribers get a free copy of Oil Fall and subscription rates are still a very reasonable $75 per year, or $7.50 per month. Soon, those rates will rise modestly to $80.00/$8.00.

Go ahead, buy a ticket to the show.

The advantages offered by EV to climate and the natural environment are well established, but erode quickly as the vehicles themselves expand in size and weight. Your correspondent wrote an e-book series over the course of 2018-2023 that explains in specific detail how EV would be adopted and powered, and would unleash energy and economic savings to the system. But most of those advantages dissipate wherever the auto industry essentially transfers those giga-vehicle designs to the EV platform, with a massive chassis and an oversized sized battery pack.

David Zipper has addressed this issue in a recent Atlantic article (subscription required) but you can pick up the main points in his twitter thread. One of his more intriguing findings that’s obvious but really merits long consideration: large truck-size EV passenger vehicles represent an outsized call on battery materials like lithium and cobalt, raising the price for vehicles which could be using those materials more optimally. There’s that word again.

Meanwhile, over at MIT’s Trancik Lab, the good folks there continually update their carbon counter tool which plots EV along with ICE to gauge lifetime energy and emissions footprints. Simply put, some very compact and efficient ICE vehicles heroically do reasonably well in the scatterplot, while some EV do quite poorly. In the live version of the tool, I have chosen to compare the stellar Hyundai Ioniq with the new Ford F-150 Lightning Pro, the all electric truck. Static screenshot of the live tool here:

As you can see, the Ioniq (2) is in the catbird seat, combining ultra low fuel and maintenance costs, while also sitting below a key level that measures grams of carbon emitted over the entire lifecycle. Wow. But the Ford Lightning (1) is up there with a number of hybrids, a far more expensive vehicle to buy and operate, and whose grams of carbon emissions are not enviable. The Gregor Letter has spoken positively about the Ford Lightning in the past, for its ability to offer power at job sites, and especially for its ability to power a home. That requires an enormous battery pack, of course. And so we return to a previous idea: a world that can make a large EV truck for use in high productivity applications is a good thing. Yes, these vehicle types embed far more raw materials. But if their work output is high, that’s a decent offset.

The problem is the use of very heavy vehicles in the discretionary, passenger auto segment, where consumers are buying these behemoths and paying no extra tax to drive them on public roads. The supersizing of passenger vehicles in the US frankly looks like a regulatory failure, more generally. And the time has come to tax non-work vehicles under an excess weight scheme. Just to remind: the idea that one should be taxed at a higher rate to reflect higher usage impact on the commons is a historically conservative concept.

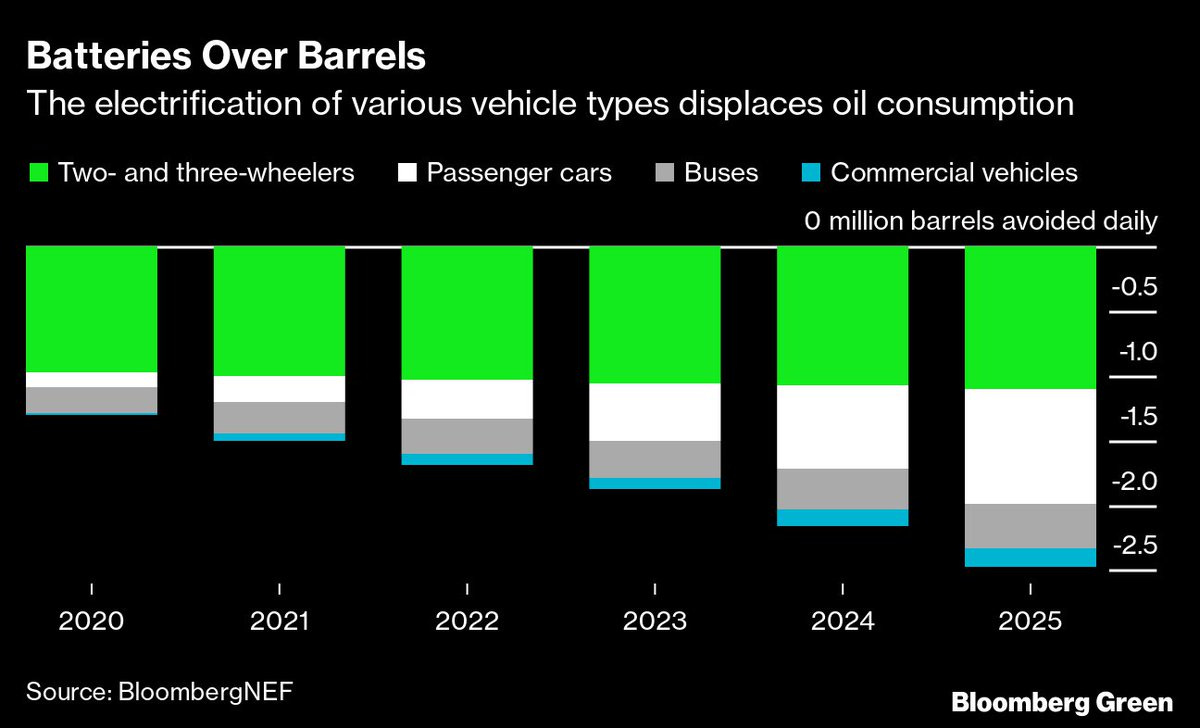

Factors that would drive future growth of oil consumption in the Non-OECD are eroding. The historically popular normalization thesis, which held that per capita consumption of oil in developing nations would eventually align with the West, has lost its way. Sorry, just not happening. The quite visible pressure bearing down on this particular consumption model is of course the rapid adoption of EV in China, and the adoption of electric 2 and 3 wheelers across the rest of Asia. Most westerners are likely not aware that the 2 and 3 wheeler market is so major that, in countries like India, the fleet’s total petrol consumption has at times either matched or exceeded that of the automobile fleet. In other words this is a giant block of current and future consumption that’s going to curtail, rather than add, to future growth as many countries incentivize adoption through emissions schemes. The other big block of future demand that’s being curtailed is of course in China’s vehicle market. (No need to put a chart up again, as The Gregor Letter constantly updates readers: 6.8 million EV sales are expected in a 27 million unit market in 2022). Unsurprisingly, BNEF is already tracking avoided oil consumption from these trends, and their conclusion looks like this:

We also need to understand that in the Non-OECD, electricity rather than oil is the primary distribution channel to lift populations out of energy-poverty. Moreover, Asia’s manufacturing sector, led by China, is also a very heavy user of electricity and will remain so. So marginal growth, led by electrification of transport, has favored, and will continue to favor electricity. And the data bears this out. In the chart below, notice the growth rate of megawatt hour consumption per capita in this century. From 2005 for example, Non-OECD MWh per capita growth is up 82% through 2021.

Now look at per capita oil consumption growth. Since 2005, Non-OECD per capita consumption of oil in barrels has grown by just 24%. Over a sixteen year period, there is nothing ferocious in that rate, well below 2%. Note also that while per capita consumption is indeed lifting, it’s coming off a stagnant twenty year base from 1980-2000. This is nothing like the 20th century rate of oil adoption in the OECD. That was a unique, one-time confluence of industrial growth and the adoption of the ICE vehicle.

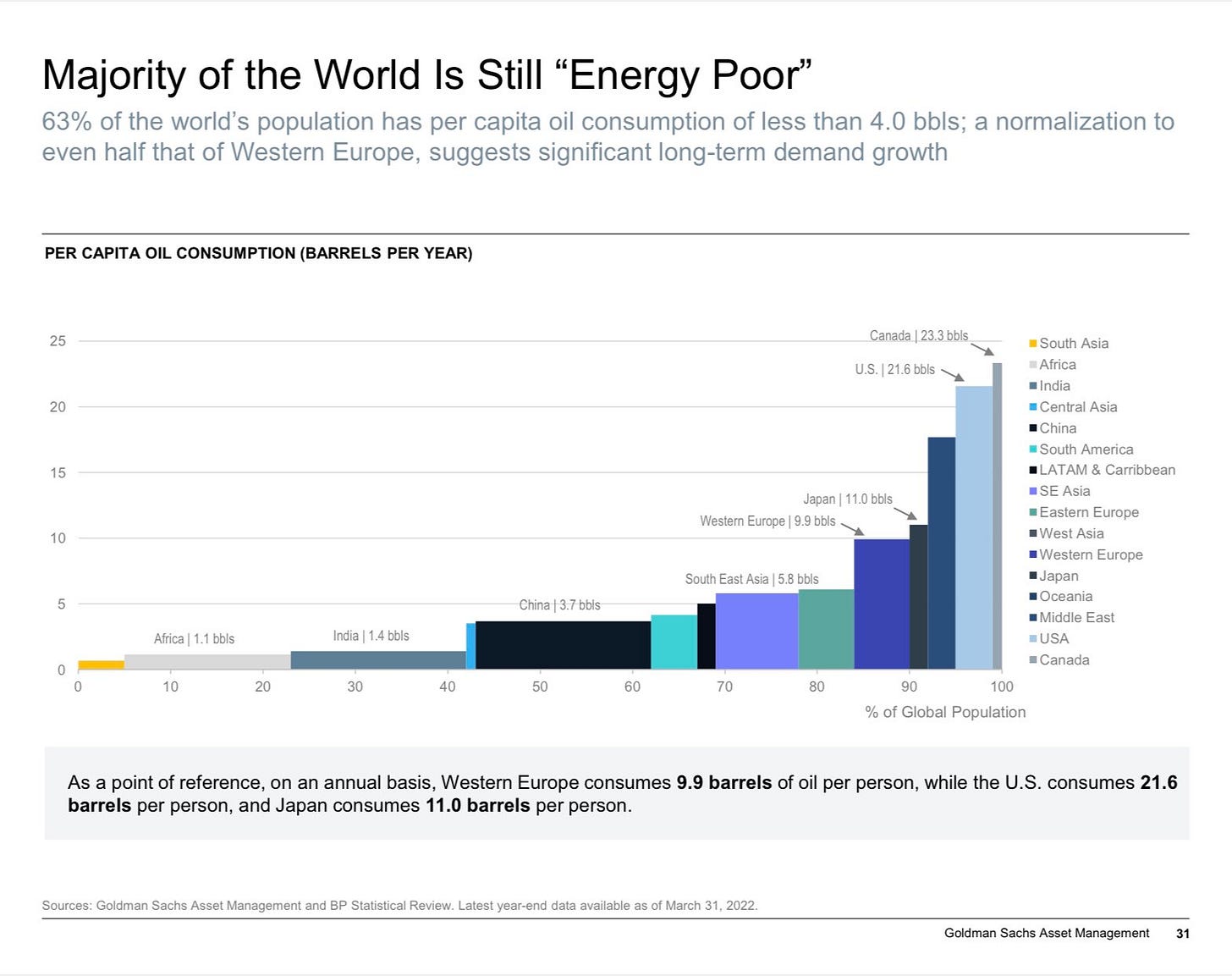

Now, just to make sure we’re not engaging in a familiar game called Whack the Strawman, let’s make it clear that not every think tank forecast over the past thirty years suggested Non-OECD was going to match OECD per capita levels. And no one is doing that today (hopefully not, for their sake!) Forecasts have been responsibly dialed back over the years but the basic idea, directionally, is still very much in play. Here for example is a chart grabbed from a recent twitter discussion, showing that Goldman analysis is thinking about the risk that Non-OECD consumption could normalize to half of per capita use in Europe. OK, fair enough. That’s a far less ambitious prospect. But consider that per capita use in the EU is leading the OECD downward: that makes for a far easier target.

And yet, there’s still no reasonable prospect that the Non-OECD gets there. Back to a central theme: notice how Goldman is thinking about energy poverty in oil terms. Dear GS: please reconsider! It’s electricity, not oil, that demands your attention when it comes to the transition out of energy poverty. The Non-OECD is already underlining this point, as per capita power consumption rises quickly, and further huge rounds of electrification in transport are to come.

• Data note: gauging per capita energy consumption relies of course not only on energy data, but population data. Here, World Bank’s estimates of OECD and Non-OECD is used but it’s important to remember that population metrics are themselves just estimates, and that population data sets can differ. In other words, your mileage may vary, but hopefully not too much across various data sets. •

Team Transitory, which got inflation terribly wrong in 2022, is going to emerge victorious. There are myriad ways to grapple with the bout of inflation that’s hit the US and the rest of the world over the past year. But a simple take is that just about every component of inflation is rolling over in successive waves. Energy and food have rolled over, along with used cars and other goods. Worries more recently focused on services, but now those are dissipating too on the back of a dramatic plunge in the ISM Services report, released last Friday.

But most newsworthy of late was the turnaround in US wage growth, contained in last Friday’s job report. Not only did wage growth slow more than forecast, but the BLS revised downward previous monthly readings too. See this thread by Harvard’s Jason Furman which is not only informative, but highlights the fact that those high wage growth readings triggered broad, inflationary concerns just one month ago.

The interest rate market responded immediately to the data, with yields falling all across the curve. While minute by minute ticker readings bounce around of course, most of the US treasury yield curve is below the Fed Funds rate with the exception of the 2 Year Treasury and the 90 Day Bill, which are hugging the area around 4.25%-4.5%. As the FOMC will meet again in early February, the interest rate futures market is pricing in a .25% rate hike. And this begs the question: as every piece of data now points downward, with the exception of the labor market, will this next hike be the last, or the penultimate?

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the 2018 single title is newly packaged and now arrives with a final installment: the 2023 update, Electric Candyland. Just hit the picture below to be taken to Dropbox Shop.